Are you lonesome tonight?

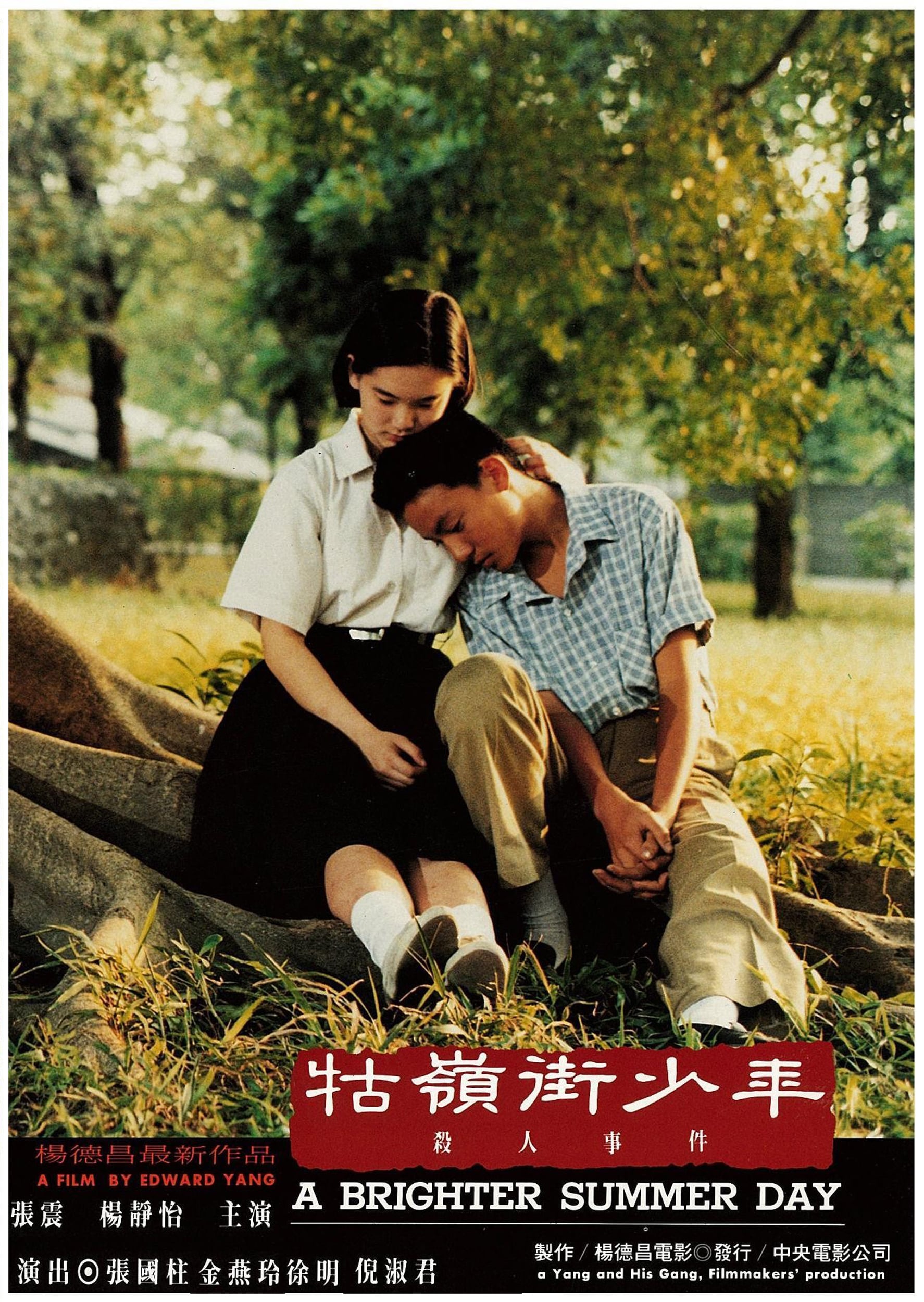

The cliché - and it is a cliché that the film justifies - is to describe A Brighter Summer Day, Edward Yang's monumental fourth feature, from 1991, as "novelistic". Indeed it is, and I can think of no word that better captures the film's sprawl (it comes in with a running time just a few minutes shy of four hours), its huge bench of characters (over one hundred speaking parts), the way its protagonist is both a very specific human being in all of his characteristics, while also feeling like an emblematic stand-in for a generation or even an entire society. It has the rich fullness of a novel, a feeling of burrowing into a world that exists far outside of the story we're being told, even as that story actively tries to suck in as much of that world as it reasonably can.

The problem with using that very tempting and very evocative word is that novels, are, well, novels: words printed on sheets of paper that are bound together. Calling a film "novelistic" always feels, to me, like it has a slightly backhanded quality, suggesting that its strengths are the ones it can borrow from other media. That is to say, if a film is novelistic, it is perhaps difficult to see how it can also be cinematic. And A Brighter Summer Day is certainly cinematic! It's a film carried along on its superb visuals, all connected to each other though a focused, consistent style that doesn't let up for a single shot across the ample running time. It's a complicated and dense marriage of grand narrative scope and impeccable formal control, but it's never the slightest bit heavy or overwhelming to watch. In fact, one of its most pleasant surprises is how quickly it speeds by, thanks in no small part to the perfection of every individual moment and shot - the film wastes nothing at all, impressive by any standards, but a downright miracle from heaven at four hours.

When one is trying to scale a mountain like this, it's good to use whatever foothold that presents itself, and the first one we encounter is the film's title. The on-screen text offers the title in both Mandarin and English, and they're completely different. The original Mandarin is one of those marathon-length titles that east Asian films often get, and the most readable translation I've encountered (I will not vouch for its accuracy) calls it The Youth Killing Incident on Guling Street. For this is, in a way, a true crime story; it's inspired by an incident that Yang recalled from his adolescence, anyways, when he was about the same age as the principles. A Brighter Summer Day is a line from the Elvis Presley song "Are You Lonesome Tonight?", which show up several times across the four hours, generally in the context of the teenage characters trying to crack the mysteries of American rock & roll as they try to form their own band.

The movie is the movie, of course, by any name, but I do wonder if one thinks of it differently based on which of those wrappers it comes in. The Youth Killing Incident on Guling Street gives it a sense of doom and fatalism: it focuses our attention on a plot event that arrives in the last ten minutes, and makes the entire feature feel like an inevitable march towards an arbitrary, foolish tragedy, coloring the whole movie with a death that comes across almost like an afterthought. A Brighter Summer Day is wistful, mournful, nostalgic: the phrase, in the context of the song, clearly indicates that a brighter summer day is something that has been lost to the past and won't be coming back. It also throws our attention on how much of the film consists of Taiwanese teenagers trying to construct a simulation of simulation of American youth culture, grabbing a foreign culture to serve as a new identity while their own cultural identity was being ripped into tatters by political forces.

Those are two wholly different films, but it speaks to the great ambition of Yang's project and the film's ampleness that A Brighter Summer Day is able to make room for both with no straining (I'm using the English title on the assumption that it's what we're all more familiar with, and because, frankly, The Youth Killing Incident on Guling Street is just a beastly-sounding pileup of words. I'm sure it sounds better in Mandarin). Under any title, this is primarily the story of 14-year-old Xiao Si'r (Chang Chen), whose name is a nickname pointing out that he's the fourth of five children, with two older sisters and an older brother, and one young sister. Si'r is the son of recent immigrants from mainland China, who fled the Maoist revolution to set up in Taipei, part of a wave of mainlanders who have substantially changed the nature of Taiwan's culture and politics. For Si'r, this shows up mostly in the tension between the gangs of Chinese teenagers and native Taiwanese, and this adolescent gang life is one of the main threads that runs through the whole film, though like every other main thread, it's sometimes much less prominent than others. All of this is established with brusque efficiency in an opening title card that give us the broad strokes of political history before dropping us into a family story; at the end of the film, that process will reverse, with an equally brusque title card that summarises an entire act worth of the film's plot, placing the intimate story back in the context of Taiwan politics. I bring this up mostly to gawk with pleasure at the elegance of the film's bookends, which both replicate and mirror each other (rather than leaving us with this telescoping out, the film ends on a quiet, intimate moment that repeats the quiet, intimate moment that follows the first title card), giving the entire 226-minute beast a clean, precise shape with just enough wiggle room for messy humanity to sneak in.

The film tells us (as all great films do) how to watch it, right from the start. A Brighter Summer Day is made up of deep shots, creating huge boxlike spaces out of the insides of houses and tunnels out of streets and alleys. Occasionally, this will be interrupted with a shallow, much closer shot of a character or two characters against a wall. By the third shot of the movie, we've seen each of these: a boxy interior, an almost infinitely deep exterior, and two people sitting close to a table. It's a simple, easy sketch of the film's primary aesthetic strategy: using close shots as the sharp, shocking punctuation marks to draw our attention to key character moments. And, indeed, to use that punctuation to define those as being the key moments in a film that otherwise is generously content to allow great developments and small ones to co-exist freely.

For A Brighter Summer Day is structured rather loosely as a series of moments, each of them feeling like a tiny, self-contained play. While there is an overall story, with a conflict and everything, it's not what's driving the film; it's more like something you notice seems to be showing up a lot more often than other kinds of scenes. This is very much a memory piece, recreating moments and places and incidents that create a very clear sense of Taipei in 1961 as a living human organism: while Si'r is the protagonist, many scenes go by without taking much if any notice of him, touching instead on his parents (Elaine Jin and Chang Kuo-Cho, Chang Chen's father), his siblings, and the tension of a Westernising young generation that's rebelling against the autocratic Taiwan government and hidebound older generations by embracing the trappings of a culturally imperialist foreign country that cares nothing about the Taiwanese, if it even thinks to notice they exist. The movie takes advantage of its length to sprawl, but never indulgently: every individual scene is so perfectly formed around its central conversation, conflict, or idea, and so perfectly staged in those diorama-like long takes that they all feel correctly-paced down to the last frame, serving a clear purpose in every step through the sets taken by every character.

The result is a movie that crystallises into shape out of several disconnected impressions, and this is how A Brighter Summer Day is able to achieve that wonderful novelistic feeling out of the stuff of cinema: it is able to look at everything, seemingly, from teen romance to political turbulence to the moral requirements of living in a society to the nuances of staging a concert, and to do it in perfect gem-like scenes of some of the finest mise en scène of the 1990s. It's a careful simulation of messy sprawl, but it's precise and perfect in its depiction of a very particular form of bleak teenage anomie in a very specific and unique time and and place, so detailed and singular that it can't help but feel like it speaks to the entire human condition as well as any film I've seen from its era.

The problem with using that very tempting and very evocative word is that novels, are, well, novels: words printed on sheets of paper that are bound together. Calling a film "novelistic" always feels, to me, like it has a slightly backhanded quality, suggesting that its strengths are the ones it can borrow from other media. That is to say, if a film is novelistic, it is perhaps difficult to see how it can also be cinematic. And A Brighter Summer Day is certainly cinematic! It's a film carried along on its superb visuals, all connected to each other though a focused, consistent style that doesn't let up for a single shot across the ample running time. It's a complicated and dense marriage of grand narrative scope and impeccable formal control, but it's never the slightest bit heavy or overwhelming to watch. In fact, one of its most pleasant surprises is how quickly it speeds by, thanks in no small part to the perfection of every individual moment and shot - the film wastes nothing at all, impressive by any standards, but a downright miracle from heaven at four hours.

When one is trying to scale a mountain like this, it's good to use whatever foothold that presents itself, and the first one we encounter is the film's title. The on-screen text offers the title in both Mandarin and English, and they're completely different. The original Mandarin is one of those marathon-length titles that east Asian films often get, and the most readable translation I've encountered (I will not vouch for its accuracy) calls it The Youth Killing Incident on Guling Street. For this is, in a way, a true crime story; it's inspired by an incident that Yang recalled from his adolescence, anyways, when he was about the same age as the principles. A Brighter Summer Day is a line from the Elvis Presley song "Are You Lonesome Tonight?", which show up several times across the four hours, generally in the context of the teenage characters trying to crack the mysteries of American rock & roll as they try to form their own band.

The movie is the movie, of course, by any name, but I do wonder if one thinks of it differently based on which of those wrappers it comes in. The Youth Killing Incident on Guling Street gives it a sense of doom and fatalism: it focuses our attention on a plot event that arrives in the last ten minutes, and makes the entire feature feel like an inevitable march towards an arbitrary, foolish tragedy, coloring the whole movie with a death that comes across almost like an afterthought. A Brighter Summer Day is wistful, mournful, nostalgic: the phrase, in the context of the song, clearly indicates that a brighter summer day is something that has been lost to the past and won't be coming back. It also throws our attention on how much of the film consists of Taiwanese teenagers trying to construct a simulation of simulation of American youth culture, grabbing a foreign culture to serve as a new identity while their own cultural identity was being ripped into tatters by political forces.

Those are two wholly different films, but it speaks to the great ambition of Yang's project and the film's ampleness that A Brighter Summer Day is able to make room for both with no straining (I'm using the English title on the assumption that it's what we're all more familiar with, and because, frankly, The Youth Killing Incident on Guling Street is just a beastly-sounding pileup of words. I'm sure it sounds better in Mandarin). Under any title, this is primarily the story of 14-year-old Xiao Si'r (Chang Chen), whose name is a nickname pointing out that he's the fourth of five children, with two older sisters and an older brother, and one young sister. Si'r is the son of recent immigrants from mainland China, who fled the Maoist revolution to set up in Taipei, part of a wave of mainlanders who have substantially changed the nature of Taiwan's culture and politics. For Si'r, this shows up mostly in the tension between the gangs of Chinese teenagers and native Taiwanese, and this adolescent gang life is one of the main threads that runs through the whole film, though like every other main thread, it's sometimes much less prominent than others. All of this is established with brusque efficiency in an opening title card that give us the broad strokes of political history before dropping us into a family story; at the end of the film, that process will reverse, with an equally brusque title card that summarises an entire act worth of the film's plot, placing the intimate story back in the context of Taiwan politics. I bring this up mostly to gawk with pleasure at the elegance of the film's bookends, which both replicate and mirror each other (rather than leaving us with this telescoping out, the film ends on a quiet, intimate moment that repeats the quiet, intimate moment that follows the first title card), giving the entire 226-minute beast a clean, precise shape with just enough wiggle room for messy humanity to sneak in.

The film tells us (as all great films do) how to watch it, right from the start. A Brighter Summer Day is made up of deep shots, creating huge boxlike spaces out of the insides of houses and tunnels out of streets and alleys. Occasionally, this will be interrupted with a shallow, much closer shot of a character or two characters against a wall. By the third shot of the movie, we've seen each of these: a boxy interior, an almost infinitely deep exterior, and two people sitting close to a table. It's a simple, easy sketch of the film's primary aesthetic strategy: using close shots as the sharp, shocking punctuation marks to draw our attention to key character moments. And, indeed, to use that punctuation to define those as being the key moments in a film that otherwise is generously content to allow great developments and small ones to co-exist freely.

For A Brighter Summer Day is structured rather loosely as a series of moments, each of them feeling like a tiny, self-contained play. While there is an overall story, with a conflict and everything, it's not what's driving the film; it's more like something you notice seems to be showing up a lot more often than other kinds of scenes. This is very much a memory piece, recreating moments and places and incidents that create a very clear sense of Taipei in 1961 as a living human organism: while Si'r is the protagonist, many scenes go by without taking much if any notice of him, touching instead on his parents (Elaine Jin and Chang Kuo-Cho, Chang Chen's father), his siblings, and the tension of a Westernising young generation that's rebelling against the autocratic Taiwan government and hidebound older generations by embracing the trappings of a culturally imperialist foreign country that cares nothing about the Taiwanese, if it even thinks to notice they exist. The movie takes advantage of its length to sprawl, but never indulgently: every individual scene is so perfectly formed around its central conversation, conflict, or idea, and so perfectly staged in those diorama-like long takes that they all feel correctly-paced down to the last frame, serving a clear purpose in every step through the sets taken by every character.

The result is a movie that crystallises into shape out of several disconnected impressions, and this is how A Brighter Summer Day is able to achieve that wonderful novelistic feeling out of the stuff of cinema: it is able to look at everything, seemingly, from teen romance to political turbulence to the moral requirements of living in a society to the nuances of staging a concert, and to do it in perfect gem-like scenes of some of the finest mise en scène of the 1990s. It's a careful simulation of messy sprawl, but it's precise and perfect in its depiction of a very particular form of bleak teenage anomie in a very specific and unique time and and place, so detailed and singular that it can't help but feel like it speaks to the entire human condition as well as any film I've seen from its era.