After the fall

Animation and surrealism - and I am here referring to surrealism in a narrower sense (though not the strictest sense), as the attempt to visually reconcile dream-reality and waking-reality into a single state, not as an intensified word for "weird" - have a difficult relationship. On the one hand, since surrealism is, in its way, dependent on the precise and total control over an image, animation seems like the natural home for it: anything can be drawn, no matter how physically impossible or improbable (and, of course, the best known examples of capital-S Surrealism are mostly paintings). On the other hand, surrealism requires jarring contrast, in the form of the subconscious rudely shoving its way into everyday realism - it must feel like a disruption, ideally an uncomfortable and violent one. Animation, no matter how much it attempts to mimic physical reality, isn't real, and it doesn't feel real. One might even go so far as to say, without exaggerating much, that animation is already surreal. So creating that important contrast becomes difficult.

But not impossible. And as you could probably guess, or why would I be going on about it, Angel's Egg is one of those rare animated films that actually manages to get surrealism exactly right. The film feels exactly like a dream, waking up and racing across a landscape that's completely inexplicable but somehow makes sense, where moments are connected by emotional logic that doesn't have anything to do with narrative comprehensibility and doesn't pretend to. The film's director, Oshii Mamoru, has claimed later on that even he doesn't know what it's about, and maybe he's just being cute, but I'm willing to take that claim at face value. What this feels like, more than anything, is the report of somebody's dream that rattled them to their core, but even they can't quite remember why or how, only that it was very perturbing, and the details are already slipping away that they can give you more like an impression of the events rather than a recounting. And then there's a visual style that gives us the drawn equivalent of all that, floating and ghostly and eerily suggestive of monochrome without being monochrome.

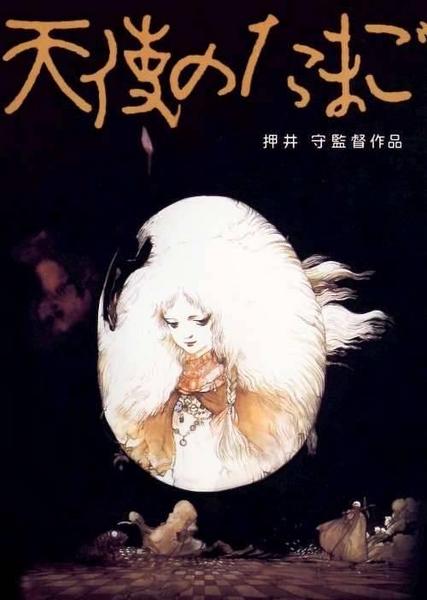

This was an early work in the career of Oshii, who would go on to become one of Japan's most famous animation director, largely on the basis of the groundbreaking Ghost in the Shell, from 1995. We should not overestimate Angel's Egg was in helping him get to that point; the 1985 OVA, or original video animation, was a critical flop that kept him from working for some time; his next job directing animation wouldn't come until 1988, when he got in on the ground floor of the Patlabor franchise. But career success isn't everything, and however well it did or didn't so for Oshii's financial prospects, it is an artistic triumph of the first order. Concerns and themes that would peak in for the rest of Oshii's career are presented here in unfiltered form, as though we've been placed directly into his id.

Or somebody's, anyway; it's important to point out that the story of Angel's Egg, if that's a fair word to use for something that's so elusive and hard to pin down as a chronicle of events, was a collaboration. Oshii wrote it with Amano Yoshitaka, who also designed the characters and the look of the world. And Amano is himself a superstar in his own field: he's an illustrator and designer in a number of different media, though I suppose he's likely best-known in the English-speaking world as the lead designer of the look of the first six entries in the Final Fantasy video game series, as well as providing promotional art and other design work for every entry since then. His characteristic style, visible across several media, is wispy and ethereal, with characters who have the loose fluidity of first-draft pencil sketches or ink wash painting. His clarity and bold coloring evoke everything from Japan's long tradition of ukiyo-e woodblock printing to the work of Gustav Klimt, somehow very busy and clean at the same time. Angel's Egg isn't by any means the sole animated feature of his career, but it it is an unusually pure expression of his design mentality, and the ghostly feeling of his drawings is perfectly realised in how the main character has been painted to have a pale pink glow about her, and the almost indescribable feeling of the backgrounds, which at once are menacing and vivid fantasy spaces, while also feeling empty, made up mostly of black nothingness.

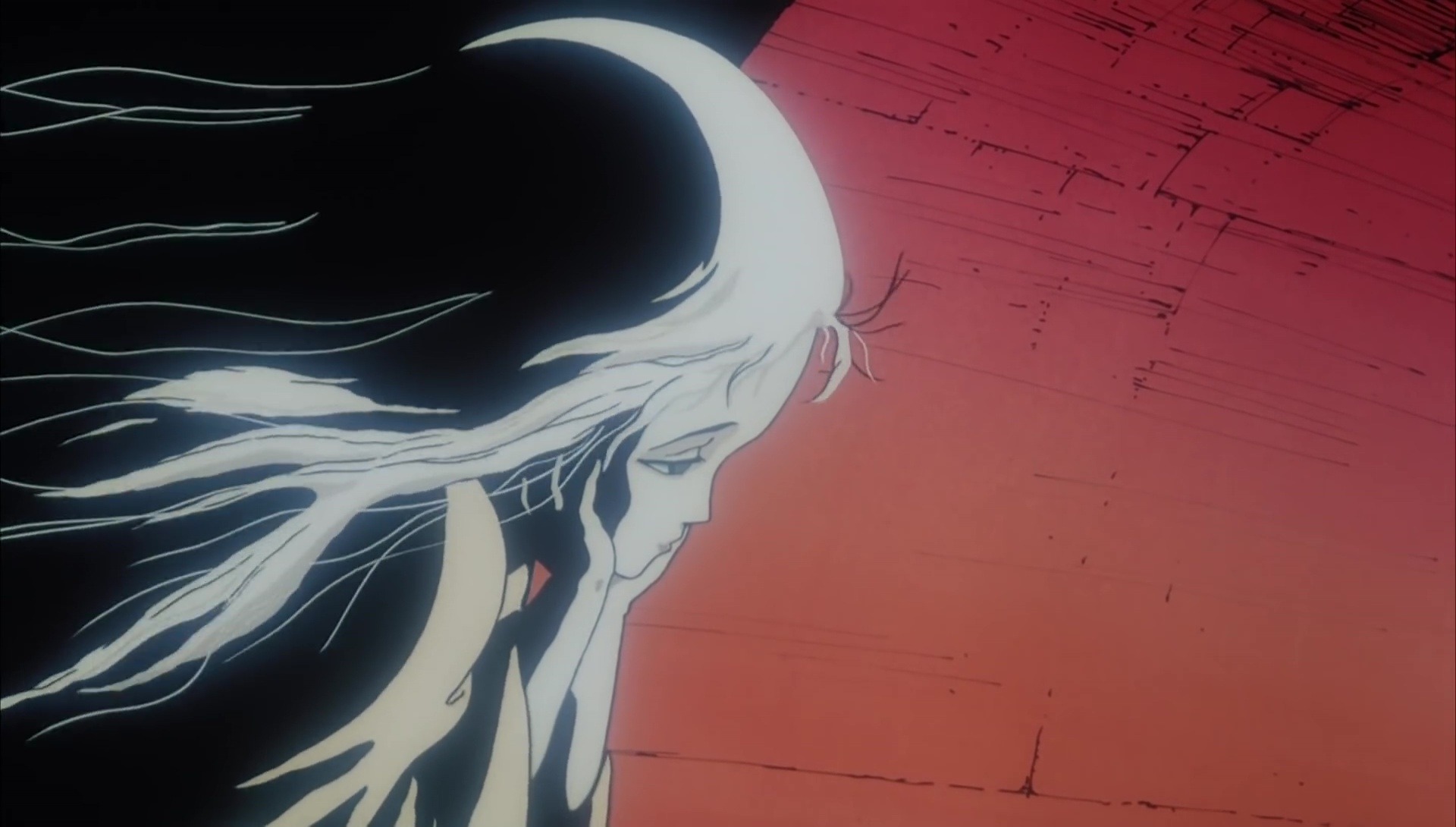

It's a style that works perfectly to evoke the film's setting, which is largely non-specific, except in that wherever we are, clearly it is ruined. And in the process of getting more ruined: while it would, I think, be correct to describe this as "post-apocalyptic", it seems as though the apocalypse is ongoing, and will likely never stop. The world is drenched in darkness and rain: it never gets brighter than the rusty red sky that shows up in an early scene, providing a suitably hellish backdrop to the image of some unfathomable war machine descending into the midst of an empty, parched landscape. There's a story in the film, and we've already seen hints of it in the very first images, which show something like an egg resting on what appears to be a dead tree, with a giant creature stirring inside of it; without wishing to ascribe meaning that Oshii and Amano may or may not have intended, it's much too close to the image of the Star Child at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey to ignore it, and in some ways it almost feels like Angel's Egg is the even more opaque and flagrantly post-human sequel to that work. But the story is riding in a comfortable third place behind the overwhelming dreamy mood of desolation and the philosophical sparring between the two central characters who we follow through this landscape.

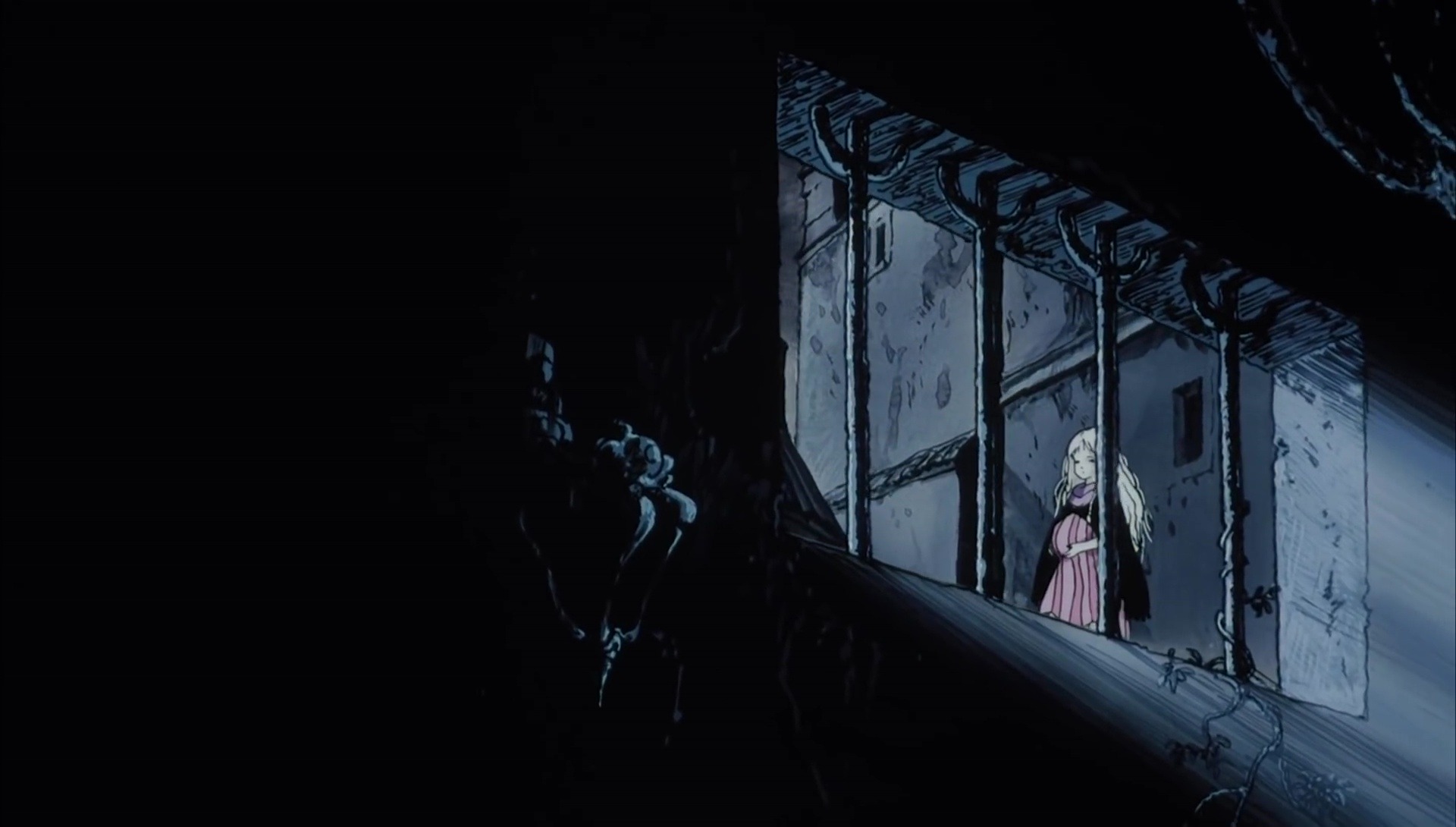

There's a young girl (Hyodo Mako), who has an egg; she doesn't know what kind of egg it is, or what to do with it, or why she has it, but she knows that she must protect. Sometimes, she tucks it under her dress, in a visual evocation of pregnancy so blunt that it's almost calming; the film has so very little that we can cling to as an anchor, that having this one thing come along and artlessly say "but whatever else happens, it has something to do with rebirth" at least makes it feel comprehensible. There's an older boy (Nezu Jinpachi), whose dress suggests someone ready for battle, though not a battle he anticipates winning. They cross paths on the streets of an empty, wrecked city, and bond, kind of; their companionship would appear to be driven more by being the only humans around, with a sort of dully resentful curiosity in each other, and shared desire not to be captured by the statue-like men who have come to the city from the war machine. At a certain point, the boy tells the story of Noah's ark, which in his version ends with despair and loss and oblivion.

If we're going to ever have a concrete answer to "what is Angel's Egg about?" that's going to have to be it: it is a retelling of the story of Noah in a world where God continued to hate mankind and never gave his absolution or forgiveness. And perhaps he is doing so now. But perhaps not.

The actual answer to "what is Angel's Egg about?" is that it's whatever it makes you feel while watching it, whatever associations you assemble from the collection of images, some of which are blatantly symbolic, some of which seem to be blatantly symbolic only there's no indication what it's a symbol for, and some of which seem to just be striking moments of beautiful desolation. The film is a dream after all, something the boy comes perilously close to stating outright: whose dream doesn't matter, I don't think. What matters is the atmosphere of dreaming: the sense that spaces are contiguous but not a way that you can necessarily trace a line between them; the way that we're always more aware of the presence of emotions than what's specifically generating those emotions; the way that it seems like everything makes perfect sense up until the moment you look directly at it and try to name it. It is a film in which the stunning amount of negative space is both a way of amplifying the sense of emptiness and loss that has saturated this world, while also making it feel like locations are unstable and half-formed.

The film is a triumph of the limited animation techniques that have always been common in Japan and were almost obligatory on a low-budget production like this: the quality of the backgrounds does a great deal of the work, while the characters are drawn with detail that would be taxing to animate, and then allowed to hold static poses for seconds at a time. Oshii is particularly great at using this to his aesthetic advantage, and Angel's Egg is a masterclass in how stillness can be generative, especially as the stillness comes to stand in for the characters' lack of knowledge or motivation. There's a great sequence in the early part of the film where the girl seems to stand still, while planes of static paintings move around her, windows sliding to find her and imprison her; it's as good an example of how one unmoving drawing can be manipulated and framed to seem dynamic and expressive as any piece of limited animation I can name. The film ends with a simple series of zoom-outs on background paintings that, coupled with Kanno Yoshihiro's harsh, weeping score (with wordless voices coming in to feel like a hollow parody of liturgy), rounds off all the film's emotions with a force that no amount of flashier, more polished animation could top.

It's a beautiful nightmare, is Angel's Egg: heavy and dark, but so ethereal that it's never actually unpleasant, as far as apocalypses go. It feels otherworldly in a way that few fantasies really try to be, and that otherworldliness gives it a strange weightlessness; it's stormy and ruined and bleak, but there's a kind of peaceful dreaminess to it, even when it is shocking and shattering and hopeless. Dreams are like that sometime, and I really don't know that I can name an animated film that feels more like floating our way through somebody else's dream. It's an unsung masterpiece, 71 minutes of pure affective power, and certainly one of the most transporting animated features I've ever seen, from Japan or anyplace.

But not impossible. And as you could probably guess, or why would I be going on about it, Angel's Egg is one of those rare animated films that actually manages to get surrealism exactly right. The film feels exactly like a dream, waking up and racing across a landscape that's completely inexplicable but somehow makes sense, where moments are connected by emotional logic that doesn't have anything to do with narrative comprehensibility and doesn't pretend to. The film's director, Oshii Mamoru, has claimed later on that even he doesn't know what it's about, and maybe he's just being cute, but I'm willing to take that claim at face value. What this feels like, more than anything, is the report of somebody's dream that rattled them to their core, but even they can't quite remember why or how, only that it was very perturbing, and the details are already slipping away that they can give you more like an impression of the events rather than a recounting. And then there's a visual style that gives us the drawn equivalent of all that, floating and ghostly and eerily suggestive of monochrome without being monochrome.

This was an early work in the career of Oshii, who would go on to become one of Japan's most famous animation director, largely on the basis of the groundbreaking Ghost in the Shell, from 1995. We should not overestimate Angel's Egg was in helping him get to that point; the 1985 OVA, or original video animation, was a critical flop that kept him from working for some time; his next job directing animation wouldn't come until 1988, when he got in on the ground floor of the Patlabor franchise. But career success isn't everything, and however well it did or didn't so for Oshii's financial prospects, it is an artistic triumph of the first order. Concerns and themes that would peak in for the rest of Oshii's career are presented here in unfiltered form, as though we've been placed directly into his id.

Or somebody's, anyway; it's important to point out that the story of Angel's Egg, if that's a fair word to use for something that's so elusive and hard to pin down as a chronicle of events, was a collaboration. Oshii wrote it with Amano Yoshitaka, who also designed the characters and the look of the world. And Amano is himself a superstar in his own field: he's an illustrator and designer in a number of different media, though I suppose he's likely best-known in the English-speaking world as the lead designer of the look of the first six entries in the Final Fantasy video game series, as well as providing promotional art and other design work for every entry since then. His characteristic style, visible across several media, is wispy and ethereal, with characters who have the loose fluidity of first-draft pencil sketches or ink wash painting. His clarity and bold coloring evoke everything from Japan's long tradition of ukiyo-e woodblock printing to the work of Gustav Klimt, somehow very busy and clean at the same time. Angel's Egg isn't by any means the sole animated feature of his career, but it it is an unusually pure expression of his design mentality, and the ghostly feeling of his drawings is perfectly realised in how the main character has been painted to have a pale pink glow about her, and the almost indescribable feeling of the backgrounds, which at once are menacing and vivid fantasy spaces, while also feeling empty, made up mostly of black nothingness.

It's a style that works perfectly to evoke the film's setting, which is largely non-specific, except in that wherever we are, clearly it is ruined. And in the process of getting more ruined: while it would, I think, be correct to describe this as "post-apocalyptic", it seems as though the apocalypse is ongoing, and will likely never stop. The world is drenched in darkness and rain: it never gets brighter than the rusty red sky that shows up in an early scene, providing a suitably hellish backdrop to the image of some unfathomable war machine descending into the midst of an empty, parched landscape. There's a story in the film, and we've already seen hints of it in the very first images, which show something like an egg resting on what appears to be a dead tree, with a giant creature stirring inside of it; without wishing to ascribe meaning that Oshii and Amano may or may not have intended, it's much too close to the image of the Star Child at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey to ignore it, and in some ways it almost feels like Angel's Egg is the even more opaque and flagrantly post-human sequel to that work. But the story is riding in a comfortable third place behind the overwhelming dreamy mood of desolation and the philosophical sparring between the two central characters who we follow through this landscape.

There's a young girl (Hyodo Mako), who has an egg; she doesn't know what kind of egg it is, or what to do with it, or why she has it, but she knows that she must protect. Sometimes, she tucks it under her dress, in a visual evocation of pregnancy so blunt that it's almost calming; the film has so very little that we can cling to as an anchor, that having this one thing come along and artlessly say "but whatever else happens, it has something to do with rebirth" at least makes it feel comprehensible. There's an older boy (Nezu Jinpachi), whose dress suggests someone ready for battle, though not a battle he anticipates winning. They cross paths on the streets of an empty, wrecked city, and bond, kind of; their companionship would appear to be driven more by being the only humans around, with a sort of dully resentful curiosity in each other, and shared desire not to be captured by the statue-like men who have come to the city from the war machine. At a certain point, the boy tells the story of Noah's ark, which in his version ends with despair and loss and oblivion.

If we're going to ever have a concrete answer to "what is Angel's Egg about?" that's going to have to be it: it is a retelling of the story of Noah in a world where God continued to hate mankind and never gave his absolution or forgiveness. And perhaps he is doing so now. But perhaps not.

The actual answer to "what is Angel's Egg about?" is that it's whatever it makes you feel while watching it, whatever associations you assemble from the collection of images, some of which are blatantly symbolic, some of which seem to be blatantly symbolic only there's no indication what it's a symbol for, and some of which seem to just be striking moments of beautiful desolation. The film is a dream after all, something the boy comes perilously close to stating outright: whose dream doesn't matter, I don't think. What matters is the atmosphere of dreaming: the sense that spaces are contiguous but not a way that you can necessarily trace a line between them; the way that we're always more aware of the presence of emotions than what's specifically generating those emotions; the way that it seems like everything makes perfect sense up until the moment you look directly at it and try to name it. It is a film in which the stunning amount of negative space is both a way of amplifying the sense of emptiness and loss that has saturated this world, while also making it feel like locations are unstable and half-formed.

The film is a triumph of the limited animation techniques that have always been common in Japan and were almost obligatory on a low-budget production like this: the quality of the backgrounds does a great deal of the work, while the characters are drawn with detail that would be taxing to animate, and then allowed to hold static poses for seconds at a time. Oshii is particularly great at using this to his aesthetic advantage, and Angel's Egg is a masterclass in how stillness can be generative, especially as the stillness comes to stand in for the characters' lack of knowledge or motivation. There's a great sequence in the early part of the film where the girl seems to stand still, while planes of static paintings move around her, windows sliding to find her and imprison her; it's as good an example of how one unmoving drawing can be manipulated and framed to seem dynamic and expressive as any piece of limited animation I can name. The film ends with a simple series of zoom-outs on background paintings that, coupled with Kanno Yoshihiro's harsh, weeping score (with wordless voices coming in to feel like a hollow parody of liturgy), rounds off all the film's emotions with a force that no amount of flashier, more polished animation could top.

It's a beautiful nightmare, is Angel's Egg: heavy and dark, but so ethereal that it's never actually unpleasant, as far as apocalypses go. It feels otherworldly in a way that few fantasies really try to be, and that otherworldliness gives it a strange weightlessness; it's stormy and ruined and bleak, but there's a kind of peaceful dreaminess to it, even when it is shocking and shattering and hopeless. Dreams are like that sometime, and I really don't know that I can name an animated film that feels more like floating our way through somebody else's dream. It's an unsung masterpiece, 71 minutes of pure affective power, and certainly one of the most transporting animated features I've ever seen, from Japan or anyplace.