Gets you jumping like a real live wire

A review requested by Brennan Klein, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

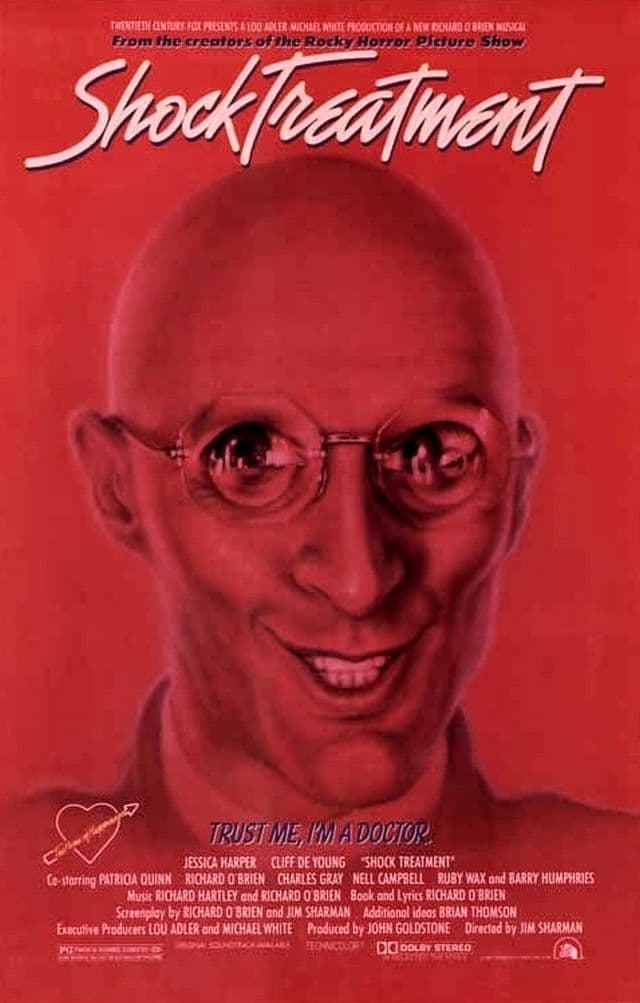

It would have taken the work of a none-too-terribly thorough rewrite to transform Shock Treatment into a film "from the creators of The Rocky Horror Picture Show", instead of an explicit (though singularly indirect) sequel to The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and it's impossible not to wonder how different the film's fate might have been if that rewrite had been carried out. Obviously, the knowledge that Rocky Horror, the cult classic to end all cult classics, has a sequel out there in the world is enough to make anybody curious, and that curiosity is likely responsible for most of Shock Treatment's audience in latter days. But I wonder if simply marketing it as the next film made by Richard O'Brien and Jim Sharman might have given it a better fighting chance to succeed when it was released to profound audience indifference in 1981. Because calling it a sequel invariably raises expectations, and not only does Shock Treatment fail to meet those expectations, there's not a shred of evidence that Shock Treatment ever considered it a priority to attempt to meet those expectations. It is a different film altogether, doing different things to arrive at different ends - so different, indeed, that one fairly quickly loses interest in comparing the two films, given how very little it yields to do so.

The film picks up a few years after Rocky Horror, or at least we can assume as much, given that the now-married Janet (Jessica Harper) and Brad Majors (Cliff De Young) have hit the point in a marriage where the couple has moved into a low-hostility boredom with each other. Incidentally, this makes for a concise way of pointing out how limited this film is as a sequel: the whole point of those characters in the earlier story was that they were boring middle-American squares who needed a good sexy shaking-up to learn to be more interesting. From the evidence of Shock Treatment, it didn't take: they're pretty damn square again, living in the very square town of Denton, which is introduced in the film's first musical number, a big ensemble piece called "Denton U.S.A.", praising the community in the most anodyne, uninspiring terms possible. What the song doesn't quite get around to clarifying is that Denton, apparently, is entirely contained within a massive TV studio, and the entire work of the community is implicated in staging, performing, or watching an endless loop of schlocky locally-produced content. Somehow, it is so much weirder than I've just made it sound.

The short version of the plot that follows is that the mad German game show host Bert Schnick (Barry Humphries) uses his maritally-themed program to determine that Brad and Janet need to be separated: he is sent to the mental hospital run by siblings Cosmo (O'Brien, who also co-wrote the screenplay and lyrics, and co-wrote the music) and Nation McKinley (Patricia Quinn), while she is plucked up by fast food magnate Farley Flavors (DeYoung), who is something between town dictator and network president, to be molded into a pop superstar. While this is going on, Betty Hapschatt (Ruby Wax) and Judge Oliver Wright (Charles Gray), who appear to have some plans for Brad and Janet that have now been thwarted, throw themselves into trying to figure out what shenanigans are afoot. This is also so much weirder than I've just made it sound.

I promised not to compare Shock Treatment too much with Rocky Horror, but one thing at this point leaps to mind. The 1975 film, and its 1973 stage precursor, have a fairly clear focus: lovingly parodying 1950s B-movies by lathering them up with the various fluidities of the 1970s sexual counterculture. Shock Treatment is a satire of television, and the way Americans allow it to colonise our brains and lives, and tell us what to purchase, and all the other things; but I am quite at a loss to explain how it goes about doing that. It's broad satire and therefore vague satire; it gets closer to hitting a defined target in the snarky "Denton U.S.A." than it ever does again for the rest of its very busy 94 minutes.

This was perhaps inevitable. The Rocky Horror Picture Show was obviously the thing it wanted to be, refined and tightened in the form of The Rocky Horror Show onstage. It had a definite form. Shock Treatment's form is fairly definite, but it largely exists as the end result of several compromises that O'Brien, co-writer and director Sharman, and producer Michael White had to make, either with various actors not wanting to return, or only wanting to return with conditions. And the film's production was also hammered by a Screen Actors Guild strike, which pushed filmmaking to England, which meant that there was no available all-American suburb to serve as a location, which is how the "city in a television studio" conceit was born. Shock Treatment didn't "want" to take this form, in other words; it adopted this form because it was the first one that outside forces didn't destroy.

Granting all of that, the film is still a hell of a thing: giddy and watchable, nervy in its weird comedy and weird images, and blessed by a pair of lead performances that seem to exactly understand what the material needs. Or maybe it's that the material shaped itself around them. I have all the love in the world for Susan Sarandon and Barry Bostwick in Rocky Horror, but they're fundamentally tourists in the movie; Harper and De Young are the cornerstones of Shock Treatment, committing 100% to the bombastic mood even when it's not clear what the bombast is all about. I can point to the exact moment I felt everything click into place: during the second number, the marital lament/power ballad "Bitchin' in the Kitchen", Harper goes straight into belting out her notes at full volume when her chorus comes around, hitting a sort of Ellen Foley-esque opera rock register right out of the gate, and De Young matches her perfectly when she hands the song back. It's fearless and reckless and doesn't have any clue what "subtlety" might even look or sound like, and from that point onward, neither actor feels like they're holding back. The film is a deranged caricature of human behavior, and they are willing to meet the film on its level, and the results are at least slightly glorious.

Indeed, Harper and De Young are so big and strange, the designated weirdos - Humphries, O'Brien, Quinn, Nell Campbell - feel almost extraneous, and I think that's maybe where Shock Treatment starts to get its own unique energy. Rocky Horror generates its attitude from setting up a contrast between clean-cut Americana and playful lechery, embodied in the very different performance styles of the leads; Shock Treatment has no such contrast. So it can start large and get larger as it goes, eventually ending at "gargantuan". It is, in this sense, more like a live-action a cartoon, with the big, caricatured energy of a zany eight-minute slapstick romp that has been expanded (without any real sense of dragging, I am happy to say) to over ten times its natural length. This is the great benefit of having to shoot the entire movie on soundstages assembled on the cheap; the film has already started out by throwing any realistic grounding out the window, instead taking place in its entirely in a weird fantasy space. That space has then been turned by production designer Brian Thomson, set decorator Ken Wheatley, and art director Andrew Sanders into a series of isolated boxes, some of them relying on bright colors, others on props, and still others on striking, damn near Expressionist lines; the cage that Brad spends most of the movie in is a keen example of the latter, boldly using white and grey as the only hues defining the spot as fundamentally at odds even with the limited coherence presented elsewhere in the film. And then, just to top things off, cinematographer Mike Molloy lights everything to be bright and shiny and distinctly flat, exaggerating the sense of television-style chintziness as well as underlinging the madly cheery colors.

It's sure as hell distinctive, whatever else we might say about it. There's a certain level of scorched-earth "all mass culture is trash" satire going on here that doesn't allow for much focus or nuance, but it's presented with a beaming smile rather than a sullen snarl, and that helps a lot. It also helps that the movie is fun. Richard O'Brien and Richard Hartley, in crafting the film's music, remain keenly aware of the importance of big, bouncy, singable moments, and so for all of the new wave influences in the soundtrack (though with a little dash of punk, glam, and classic rock, it is more generically wide-ranging than Rocky Horror, which was pretty much all glam), the music retains the robust energy of Broadway musical comedy, and the result is a soundtrack that's every bit as ear-wormy as the first movie, although other than maybe just "Bitchin' in the Kitchen", the lyrics are somewhat less witty. And the characters are all so broad and silly that it's hard not to enjoy spending time in their company, at the level of pure cartoon joy. The movie might have been compromised on its way to production, but it never feels that way; in all its ungainly messiness, this is a movie that feels like the unbridled expression of whatever the filmmakers thought would be appealingly strange on a moment to moment basis. It's a movie that never once apologises for itself or tries to meet a viewer's expectations, instead delighting in how very zany and madcap it is, and I would far rather have a befuddling, chaotic mess with that kind of unfettered zaniness than... well, just about anything, really.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

It would have taken the work of a none-too-terribly thorough rewrite to transform Shock Treatment into a film "from the creators of The Rocky Horror Picture Show", instead of an explicit (though singularly indirect) sequel to The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and it's impossible not to wonder how different the film's fate might have been if that rewrite had been carried out. Obviously, the knowledge that Rocky Horror, the cult classic to end all cult classics, has a sequel out there in the world is enough to make anybody curious, and that curiosity is likely responsible for most of Shock Treatment's audience in latter days. But I wonder if simply marketing it as the next film made by Richard O'Brien and Jim Sharman might have given it a better fighting chance to succeed when it was released to profound audience indifference in 1981. Because calling it a sequel invariably raises expectations, and not only does Shock Treatment fail to meet those expectations, there's not a shred of evidence that Shock Treatment ever considered it a priority to attempt to meet those expectations. It is a different film altogether, doing different things to arrive at different ends - so different, indeed, that one fairly quickly loses interest in comparing the two films, given how very little it yields to do so.

The film picks up a few years after Rocky Horror, or at least we can assume as much, given that the now-married Janet (Jessica Harper) and Brad Majors (Cliff De Young) have hit the point in a marriage where the couple has moved into a low-hostility boredom with each other. Incidentally, this makes for a concise way of pointing out how limited this film is as a sequel: the whole point of those characters in the earlier story was that they were boring middle-American squares who needed a good sexy shaking-up to learn to be more interesting. From the evidence of Shock Treatment, it didn't take: they're pretty damn square again, living in the very square town of Denton, which is introduced in the film's first musical number, a big ensemble piece called "Denton U.S.A.", praising the community in the most anodyne, uninspiring terms possible. What the song doesn't quite get around to clarifying is that Denton, apparently, is entirely contained within a massive TV studio, and the entire work of the community is implicated in staging, performing, or watching an endless loop of schlocky locally-produced content. Somehow, it is so much weirder than I've just made it sound.

The short version of the plot that follows is that the mad German game show host Bert Schnick (Barry Humphries) uses his maritally-themed program to determine that Brad and Janet need to be separated: he is sent to the mental hospital run by siblings Cosmo (O'Brien, who also co-wrote the screenplay and lyrics, and co-wrote the music) and Nation McKinley (Patricia Quinn), while she is plucked up by fast food magnate Farley Flavors (DeYoung), who is something between town dictator and network president, to be molded into a pop superstar. While this is going on, Betty Hapschatt (Ruby Wax) and Judge Oliver Wright (Charles Gray), who appear to have some plans for Brad and Janet that have now been thwarted, throw themselves into trying to figure out what shenanigans are afoot. This is also so much weirder than I've just made it sound.

I promised not to compare Shock Treatment too much with Rocky Horror, but one thing at this point leaps to mind. The 1975 film, and its 1973 stage precursor, have a fairly clear focus: lovingly parodying 1950s B-movies by lathering them up with the various fluidities of the 1970s sexual counterculture. Shock Treatment is a satire of television, and the way Americans allow it to colonise our brains and lives, and tell us what to purchase, and all the other things; but I am quite at a loss to explain how it goes about doing that. It's broad satire and therefore vague satire; it gets closer to hitting a defined target in the snarky "Denton U.S.A." than it ever does again for the rest of its very busy 94 minutes.

This was perhaps inevitable. The Rocky Horror Picture Show was obviously the thing it wanted to be, refined and tightened in the form of The Rocky Horror Show onstage. It had a definite form. Shock Treatment's form is fairly definite, but it largely exists as the end result of several compromises that O'Brien, co-writer and director Sharman, and producer Michael White had to make, either with various actors not wanting to return, or only wanting to return with conditions. And the film's production was also hammered by a Screen Actors Guild strike, which pushed filmmaking to England, which meant that there was no available all-American suburb to serve as a location, which is how the "city in a television studio" conceit was born. Shock Treatment didn't "want" to take this form, in other words; it adopted this form because it was the first one that outside forces didn't destroy.

Granting all of that, the film is still a hell of a thing: giddy and watchable, nervy in its weird comedy and weird images, and blessed by a pair of lead performances that seem to exactly understand what the material needs. Or maybe it's that the material shaped itself around them. I have all the love in the world for Susan Sarandon and Barry Bostwick in Rocky Horror, but they're fundamentally tourists in the movie; Harper and De Young are the cornerstones of Shock Treatment, committing 100% to the bombastic mood even when it's not clear what the bombast is all about. I can point to the exact moment I felt everything click into place: during the second number, the marital lament/power ballad "Bitchin' in the Kitchen", Harper goes straight into belting out her notes at full volume when her chorus comes around, hitting a sort of Ellen Foley-esque opera rock register right out of the gate, and De Young matches her perfectly when she hands the song back. It's fearless and reckless and doesn't have any clue what "subtlety" might even look or sound like, and from that point onward, neither actor feels like they're holding back. The film is a deranged caricature of human behavior, and they are willing to meet the film on its level, and the results are at least slightly glorious.

Indeed, Harper and De Young are so big and strange, the designated weirdos - Humphries, O'Brien, Quinn, Nell Campbell - feel almost extraneous, and I think that's maybe where Shock Treatment starts to get its own unique energy. Rocky Horror generates its attitude from setting up a contrast between clean-cut Americana and playful lechery, embodied in the very different performance styles of the leads; Shock Treatment has no such contrast. So it can start large and get larger as it goes, eventually ending at "gargantuan". It is, in this sense, more like a live-action a cartoon, with the big, caricatured energy of a zany eight-minute slapstick romp that has been expanded (without any real sense of dragging, I am happy to say) to over ten times its natural length. This is the great benefit of having to shoot the entire movie on soundstages assembled on the cheap; the film has already started out by throwing any realistic grounding out the window, instead taking place in its entirely in a weird fantasy space. That space has then been turned by production designer Brian Thomson, set decorator Ken Wheatley, and art director Andrew Sanders into a series of isolated boxes, some of them relying on bright colors, others on props, and still others on striking, damn near Expressionist lines; the cage that Brad spends most of the movie in is a keen example of the latter, boldly using white and grey as the only hues defining the spot as fundamentally at odds even with the limited coherence presented elsewhere in the film. And then, just to top things off, cinematographer Mike Molloy lights everything to be bright and shiny and distinctly flat, exaggerating the sense of television-style chintziness as well as underlinging the madly cheery colors.

It's sure as hell distinctive, whatever else we might say about it. There's a certain level of scorched-earth "all mass culture is trash" satire going on here that doesn't allow for much focus or nuance, but it's presented with a beaming smile rather than a sullen snarl, and that helps a lot. It also helps that the movie is fun. Richard O'Brien and Richard Hartley, in crafting the film's music, remain keenly aware of the importance of big, bouncy, singable moments, and so for all of the new wave influences in the soundtrack (though with a little dash of punk, glam, and classic rock, it is more generically wide-ranging than Rocky Horror, which was pretty much all glam), the music retains the robust energy of Broadway musical comedy, and the result is a soundtrack that's every bit as ear-wormy as the first movie, although other than maybe just "Bitchin' in the Kitchen", the lyrics are somewhat less witty. And the characters are all so broad and silly that it's hard not to enjoy spending time in their company, at the level of pure cartoon joy. The movie might have been compromised on its way to production, but it never feels that way; in all its ungainly messiness, this is a movie that feels like the unbridled expression of whatever the filmmakers thought would be appealingly strange on a moment to moment basis. It's a movie that never once apologises for itself or tries to meet a viewer's expectations, instead delighting in how very zany and madcap it is, and I would far rather have a befuddling, chaotic mess with that kind of unfettered zaniness than... well, just about anything, really.