Dirty, disgusting, filthy, lice-ridden birds

The mid-budget serious prestige drama has become an endangered species in 2010s cinema, we all know this. It's a shame, but it has at least one positive benefit, which is that classic Oscarbait has become less common over the past few years. Oh, there are still the usual cradle-to-grave biopics and literary adaptations and Commentaries On The Issues, like there have been since the 1930s - and they even still win the big awards from time to time - but where it used to be that we'd have to fend off a good couple of dozen every fall, they seem to have turned into a mere trickle of just a few big players. Or at least this is my observation.

Good news for lovers of the most arid middlebrow mediocrity, because The Goldfinch is just about the most Oscarbaity Oscarbait I can think of since, God, I don't know, Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close? It's based on a 2013 novel by Donna Tartt that hits the sweet spot of being both a bestseller and a major award winner (the 2014 Pulitzer Prize, no less); its cast includes a mix of prestige-friendly warhorses (Nicole Kidman, Jeffrey Wright), up-and-coming young stars with lots of name recognition for their price (Ansel Elgort, Finn Wolfhard), and beloved character actors (Luke Wilson, Sarah Paulson). Director John Crowley's last film was a Best Picture Oscar nominee, Brooklyn, and screenwriter Peter Straughan has a Best Adapted Screenplay nomination to his credit, for the 2011 Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (his last film was 2017's The Snowman, which I imagine he and everyone else involved would like us to overlook). To put a gold-kissed cherry in a dusty sunbeam on top of it, the film was shot by the legend and awards-magnet Roger Deakins, his very first released project after finally winning his damn Oscar already.

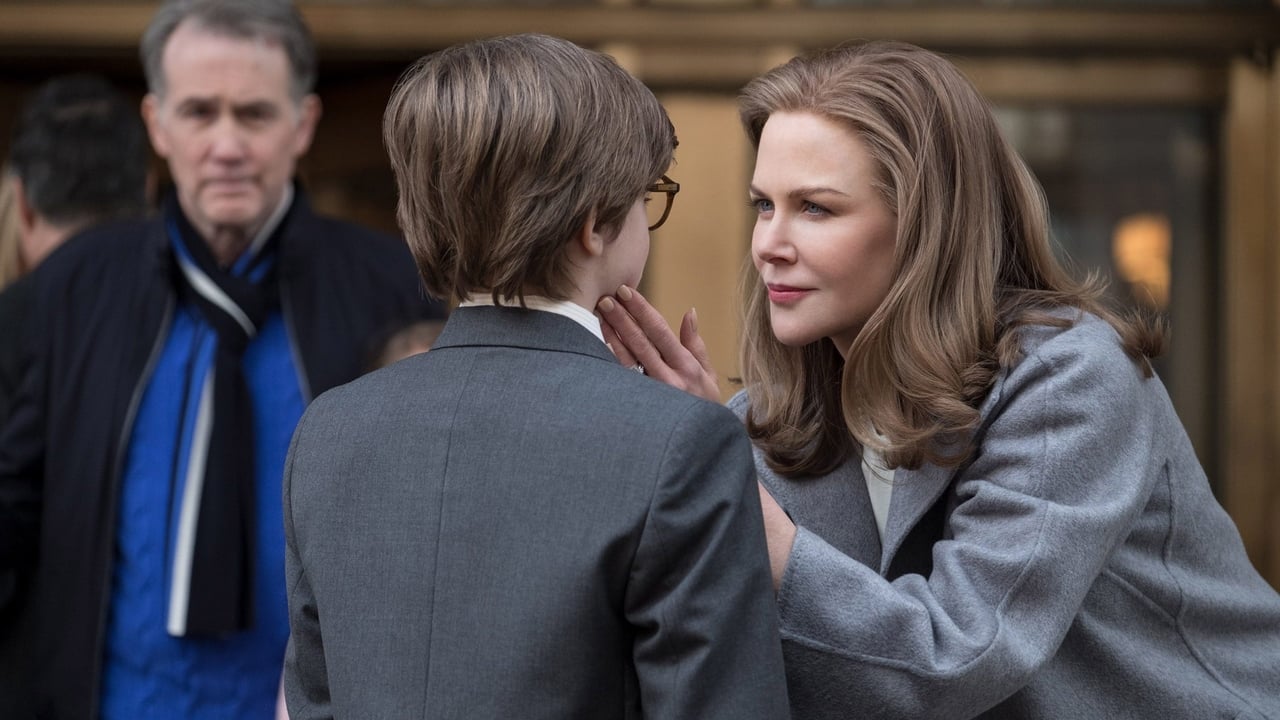

Given all of that, it is perhaps not a requirement of the form that The Goldfinch should also be an inert, nearly unwatchable trudge through two hours and twenty-nine minutes of unsmiling mud. But it doesn't hurt the case. The story is an achingly serious tour of a great many notions that don't in any significant way cohere into one story: Dutch Golden Age painters, antiques, the Russian mafia, antique fraud, drug addiction, the subtle class conflicts among gradations of the upper-middle-class in New York, adolescent male homosociality, and above it all, the cloudy ghost of 9/11. The last of these provides the partially nonlinear film with its bookends: it opens in the immediate aftermath of a bombing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which leaves 13-year-old Theo Decker (Oakes Fegley) in an ash-covered daze, with a dead mother left behind in the rubble. He's placed with the Barbours, the closest thing he has to family friends (it's not very close), where he is slowly but surely taken in as an adopted son by Samantha (Kidman) and as a brother by young Andy (Ryan Foust), while the rest of the clan regards him with the kindly contempt that goes hand-in-hand with noblesse oblige. He also meets up with "Hobie" Hobart (Wright), an aging antiques restorer who appeals to the boy's love of fusty old art, and Hobie's dead business partner's niece Pippa (Aimee Laurence).

After a while, his erstwhile father Larry (Wilson) and Larry's trashy new girlfriend Xandra (Paulson) rip him out of his pleasant new life to strand him in Las Vegas, where he only has one friend, Boris (Wolfhard) the precocious son of a shady Ukrainian businessman. After Larry's possibly mob-related death, Theo manages to escape back to New York, where he grows up (and becomes Elgort), resuscitates Hobie's business, re-encounters the Barbours, who have suffered tragedy, and makes terrible choices as a result of the litany of pills he's ended up addicted to thanks to Boris's influence. Through all of this, he carries around a talisman of that horrible day at the museum, a painting he stole from the rubble mostly without thinking: The Goldfinch, one of the final pieces completed by Carel Fabritius before his death at the age of 32, in 1654. His death by explosion, a little historical echo that's maybe the only element of the film that isn't horribly overdetermined.

That's a whole lot of stuff, and the closest that the filmmakers come to structuring it is to loosely assemble all of it into five roughly equal-length segments that largely, but not exclusively, play out in chronological order. I have not read Tartt's book, but I have to imagine this all worked better in the form of a novel: the narrative sprawl, and the promiscuous assembly of wildly disjointed fun facts about history and art (much of it plainly intended to be more digressive than even a grotesquely overlong feature film has room for) feel like the kind of stuff that needs the leisurely, let's-chase-down-ideas formlessness of a bildungsroman. Not to mention the ability to visualise all of this rather than seeing it: I'm not sure that pressing a globe-trotting heist involving gangsters and lovingly detailed furniture pornography into a hushed story about childhood post-traumatic stress disorder poisoning adulthood was ever going to work, but it definitely doesn't work when we can see and hear all of these various ingredients, and directly compare them. Paulson's ghoulish approximation of a blowsy Vegas prostitute and Wolfhard's Rocky and Bullwinkle-level Ukrainian accent probably wouldn't even pass muster in a vacuum, but asking them to inhabit the same scenes - the same shots! - makes the sheer cartoon garishness of those characters pop out, and they're far more close tonally and energetically than either is to the gravely soft-lit scenes of Kidman primly indicating portraits. Though they're not so far from the scenes of Kidman wearing the most unholy old-age prosthetics and wig that an openly hostile hair and make-up department could whip up for her.

It's a mishmash, that's all there is to it. Crowley attempts to deal with this by lacquering the whole movie with a uniform layer of sobriety and whispery earnestness; this gets us through the scenes in New York well enough, but the misadventures in Las Vegas, on top of whatever the shit is going on for the last 25 minutes, are so over-the-top and heightened that treating them with any sincerity whatsoever only serves to amplify how ridiculous and unacceptable this all is (I really, truly don't know if I have the words to express how much I detest what the film does with Larry and Xandra: tonally, narratively, visually, performatively. It is a new feeling for me to despise what Sarah Paulson is up to in front of a movie camera, but I would absolutely not mind scrubbing every bit of her work here from my brain). The heavy running time is completely useless: it's much too short to fit everything in without having most of it feel rushed, but it's also so lethargic and puffy that the whole thing feels like it's on quaaludes.

Deakins is doing good work, at least, which makes him a rarity among the crew heads and lead actors; I don't want to go crazy attacking every aspect of the film, but this is the kind of overburdened production where even the set decoration feels both over-fussed and inhumane, like every single location is a model home that the crew didn't have time to redress before shooting. It's just a completely misbegotten affair all around, stiffly acted and airless in its style and profoundly boring when it isn't profoundly stupid as a story. Just about the best thing I can say is that it's a relief that the film was effectively euthanised with its release date even before awards season got going; there's at least enough brain power in the industry left to recognise that this was an utter failure, even if there wasn't enough to keep from making it in the first place.

Good news for lovers of the most arid middlebrow mediocrity, because The Goldfinch is just about the most Oscarbaity Oscarbait I can think of since, God, I don't know, Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close? It's based on a 2013 novel by Donna Tartt that hits the sweet spot of being both a bestseller and a major award winner (the 2014 Pulitzer Prize, no less); its cast includes a mix of prestige-friendly warhorses (Nicole Kidman, Jeffrey Wright), up-and-coming young stars with lots of name recognition for their price (Ansel Elgort, Finn Wolfhard), and beloved character actors (Luke Wilson, Sarah Paulson). Director John Crowley's last film was a Best Picture Oscar nominee, Brooklyn, and screenwriter Peter Straughan has a Best Adapted Screenplay nomination to his credit, for the 2011 Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (his last film was 2017's The Snowman, which I imagine he and everyone else involved would like us to overlook). To put a gold-kissed cherry in a dusty sunbeam on top of it, the film was shot by the legend and awards-magnet Roger Deakins, his very first released project after finally winning his damn Oscar already.

Given all of that, it is perhaps not a requirement of the form that The Goldfinch should also be an inert, nearly unwatchable trudge through two hours and twenty-nine minutes of unsmiling mud. But it doesn't hurt the case. The story is an achingly serious tour of a great many notions that don't in any significant way cohere into one story: Dutch Golden Age painters, antiques, the Russian mafia, antique fraud, drug addiction, the subtle class conflicts among gradations of the upper-middle-class in New York, adolescent male homosociality, and above it all, the cloudy ghost of 9/11. The last of these provides the partially nonlinear film with its bookends: it opens in the immediate aftermath of a bombing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which leaves 13-year-old Theo Decker (Oakes Fegley) in an ash-covered daze, with a dead mother left behind in the rubble. He's placed with the Barbours, the closest thing he has to family friends (it's not very close), where he is slowly but surely taken in as an adopted son by Samantha (Kidman) and as a brother by young Andy (Ryan Foust), while the rest of the clan regards him with the kindly contempt that goes hand-in-hand with noblesse oblige. He also meets up with "Hobie" Hobart (Wright), an aging antiques restorer who appeals to the boy's love of fusty old art, and Hobie's dead business partner's niece Pippa (Aimee Laurence).

After a while, his erstwhile father Larry (Wilson) and Larry's trashy new girlfriend Xandra (Paulson) rip him out of his pleasant new life to strand him in Las Vegas, where he only has one friend, Boris (Wolfhard) the precocious son of a shady Ukrainian businessman. After Larry's possibly mob-related death, Theo manages to escape back to New York, where he grows up (and becomes Elgort), resuscitates Hobie's business, re-encounters the Barbours, who have suffered tragedy, and makes terrible choices as a result of the litany of pills he's ended up addicted to thanks to Boris's influence. Through all of this, he carries around a talisman of that horrible day at the museum, a painting he stole from the rubble mostly without thinking: The Goldfinch, one of the final pieces completed by Carel Fabritius before his death at the age of 32, in 1654. His death by explosion, a little historical echo that's maybe the only element of the film that isn't horribly overdetermined.

That's a whole lot of stuff, and the closest that the filmmakers come to structuring it is to loosely assemble all of it into five roughly equal-length segments that largely, but not exclusively, play out in chronological order. I have not read Tartt's book, but I have to imagine this all worked better in the form of a novel: the narrative sprawl, and the promiscuous assembly of wildly disjointed fun facts about history and art (much of it plainly intended to be more digressive than even a grotesquely overlong feature film has room for) feel like the kind of stuff that needs the leisurely, let's-chase-down-ideas formlessness of a bildungsroman. Not to mention the ability to visualise all of this rather than seeing it: I'm not sure that pressing a globe-trotting heist involving gangsters and lovingly detailed furniture pornography into a hushed story about childhood post-traumatic stress disorder poisoning adulthood was ever going to work, but it definitely doesn't work when we can see and hear all of these various ingredients, and directly compare them. Paulson's ghoulish approximation of a blowsy Vegas prostitute and Wolfhard's Rocky and Bullwinkle-level Ukrainian accent probably wouldn't even pass muster in a vacuum, but asking them to inhabit the same scenes - the same shots! - makes the sheer cartoon garishness of those characters pop out, and they're far more close tonally and energetically than either is to the gravely soft-lit scenes of Kidman primly indicating portraits. Though they're not so far from the scenes of Kidman wearing the most unholy old-age prosthetics and wig that an openly hostile hair and make-up department could whip up for her.

It's a mishmash, that's all there is to it. Crowley attempts to deal with this by lacquering the whole movie with a uniform layer of sobriety and whispery earnestness; this gets us through the scenes in New York well enough, but the misadventures in Las Vegas, on top of whatever the shit is going on for the last 25 minutes, are so over-the-top and heightened that treating them with any sincerity whatsoever only serves to amplify how ridiculous and unacceptable this all is (I really, truly don't know if I have the words to express how much I detest what the film does with Larry and Xandra: tonally, narratively, visually, performatively. It is a new feeling for me to despise what Sarah Paulson is up to in front of a movie camera, but I would absolutely not mind scrubbing every bit of her work here from my brain). The heavy running time is completely useless: it's much too short to fit everything in without having most of it feel rushed, but it's also so lethargic and puffy that the whole thing feels like it's on quaaludes.

Deakins is doing good work, at least, which makes him a rarity among the crew heads and lead actors; I don't want to go crazy attacking every aspect of the film, but this is the kind of overburdened production where even the set decoration feels both over-fussed and inhumane, like every single location is a model home that the crew didn't have time to redress before shooting. It's just a completely misbegotten affair all around, stiffly acted and airless in its style and profoundly boring when it isn't profoundly stupid as a story. Just about the best thing I can say is that it's a relief that the film was effectively euthanised with its release date even before awards season got going; there's at least enough brain power in the industry left to recognise that this was an utter failure, even if there wasn't enough to keep from making it in the first place.