A review in brief

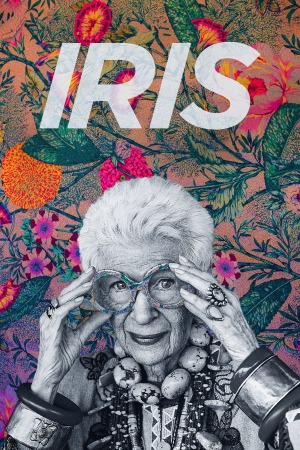

The last films of great directors inherently come with an unfair amount of baggage, and the notion that the late Albert Maysles - who, with his even later brother David, did much to help define the new genre of documentary film known as direct cinema in the '60s - would end his career with a puff piece about a fashionista is, on the surface, odd and perhaps disappointing. But Iris, a snapshot in the life of nonogenarion Iris Apfel, is hardly a trivial celebrity profile. Or, for that matter, much of a study of the fashion industry.

Instead, it's a celebration of doing what the hell you want to in old age, because at that point you've earned it. Apfel gained prominence in the 1950s with her husband Carl (who also appears in the film, surviving until August 2015), scouring the weirdest corners of the world to find interesting and delightful things to assemble into highly idiosyncratic but imaginative statements of personal style, both in clothing and interior design, and into her senior years - the film was shot when she was 90, she still pursues that goal with more vigor than many of us a fraction of her age can summon for our own passion projects. The approximate context for the film is a retrospective of Apfel's work held at the Museum of Modern Art, but she doesn't stand still to be memorialsed and stuffed; she takes an active role in helping to shape the exhibit, choosing how to define and present her life's work to best effect.

All of this would add up to a charming and thoroughly slight "aren't charming old people just, well, charming!" lark - the 79-minute running time encourages us to think of it that way, too - except for one thing. Iris Apfel, of course, isn't the only person in the film doing what they love to do long past retirement age; Maysles himself, well along into his 80s, fits that bill as well. The film doesn't let you forget that fact, either. Considering that his aesthetic was built on the rock of "the filmmaker must disappear invisibly into the background of his film", it's astonishing how much Iris draws him in, mostly because Iris, herself, draws him in, constantly gesturing to the offscreen director & cameraman, talking about how she's the subject of the movie. It's a startling departure, but it works; it even feels necessary, perhaps.

The way that Apfel inveigles Maysles into acknowledging himself in his own film feels unforced and friendly; perhaps in spotting another old fogey who won't give up, she regards him as just one more of the friends she always has encircling her, a natural part of her life in this moment. It's unexpected, but completely authentic, and it gives Iris a sense of familiarity with both its subject and its creator that make it feel like an especially realistic portrait of human life even by the standards of an inherently realistic genre.

Instead, it's a celebration of doing what the hell you want to in old age, because at that point you've earned it. Apfel gained prominence in the 1950s with her husband Carl (who also appears in the film, surviving until August 2015), scouring the weirdest corners of the world to find interesting and delightful things to assemble into highly idiosyncratic but imaginative statements of personal style, both in clothing and interior design, and into her senior years - the film was shot when she was 90, she still pursues that goal with more vigor than many of us a fraction of her age can summon for our own passion projects. The approximate context for the film is a retrospective of Apfel's work held at the Museum of Modern Art, but she doesn't stand still to be memorialsed and stuffed; she takes an active role in helping to shape the exhibit, choosing how to define and present her life's work to best effect.

All of this would add up to a charming and thoroughly slight "aren't charming old people just, well, charming!" lark - the 79-minute running time encourages us to think of it that way, too - except for one thing. Iris Apfel, of course, isn't the only person in the film doing what they love to do long past retirement age; Maysles himself, well along into his 80s, fits that bill as well. The film doesn't let you forget that fact, either. Considering that his aesthetic was built on the rock of "the filmmaker must disappear invisibly into the background of his film", it's astonishing how much Iris draws him in, mostly because Iris, herself, draws him in, constantly gesturing to the offscreen director & cameraman, talking about how she's the subject of the movie. It's a startling departure, but it works; it even feels necessary, perhaps.

The way that Apfel inveigles Maysles into acknowledging himself in his own film feels unforced and friendly; perhaps in spotting another old fogey who won't give up, she regards him as just one more of the friends she always has encircling her, a natural part of her life in this moment. It's unexpected, but completely authentic, and it gives Iris a sense of familiarity with both its subject and its creator that make it feel like an especially realistic portrait of human life even by the standards of an inherently realistic genre.

Categories: documentaries