Getting the bandage back together

In 1964, Hammer Films was in the midst of its most prolific era of making popular genre films - at a glance I'd set the golden years between '62 and '67, with the balance favoring the middle of that window - having turned the early Gothic horror successes into a brand name in virtually no time at all, and firmly entrenching itself as the English-speaking world's most reliable vendor of edgy horror and horror-adjacent cinema. We needn't rehearse the titles; it was simply a fine time for the company's very characteristic style, and indeed it was over this period that the style became fully characteristic. All of which makes it especially hard to stomach The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb which isn't a sequel to Hammer's 1959 version of The Mummy at all, but I don't know what else to call it; a spin-off? A spiritual remake? A ratty cash-in? Yeah, let's go with that last one.

For the really, incredibly obvious thing about The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb, as becomes obvious from the instant the opening credits start up, is that it is cheap as all hell. Those credits take place over a single long take of the camera moving across a pile of ancient riches taken from (presumably) a mummy's tomb, and between the flat lighting and the quality of the props, there's no doubting at all that we're looking at plaster and plastic and desperation; there might not ever be a point in the rest of the film where that looks as patently artificial, but there's hardly anything that seriously challenges this first impression. And this is especially sad, because if there was one thing that made Hammer Films special from a production standpoint, it's the creative ways the directors and cinematographers found to hide the low budget. Just a year prior, Hammer had produced The Pirates of Blood River, a movie seemingly designed from the ground up to prove that you could make an exciting pirate film without having enough money to set any scenes onboard a ship.

And yet here's The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb, looking as tattered and chintzy as any Poverty Row film from the '40s. The indifferently-painted backdrops, the unconvincing make-up: this is, I think, what happens when you have people without training in making these kind of low-budget, atmosphere-driven horror films bear the weight fo making. For the problems, though they extend beyond the lighting, are always made worst because of the lighting, as though cinematographer Otto Heller had absolutely no clue how to deal with the emotional needs of the genre. Which, given the total absence of horror anywhere else in his filmography, is almost certainly the case.

For there is one of the other problems, surely the biggest single reason that this picture feels hardly at all like a Hammer film: it is hardly a Hammer film. For reasons that a sufficiently devoted researcher could undoubtedly scrounge up, if he was motivated for whatever reason to pretend that this film was worth the time, The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb wasn't shot at Hammer's home turf of Bray Studios, but at Elstree Studios, and almost entirely with people who lacked any previous experience with the production company. The most important Hammer veteran in the crew, in fact, was producer/director/writer Michael Carreras, son of the company's co-founder Sir James Carreras, and responsible for producing the lion's share of movies released during the company's best years. He was not, however, nearly as prolific a director, and there is not much of anything in this movie to suggest that this was a terrible loss to the corpus of British horror. It is a singularly tension-free movie that Carreras wrought; almost more interesting in being a mystery-slash-treasure hunt to bother being a thriller about a rampaging mummy.

The film opens in Egypt in 1900, in the company of a man (Bernard Rebel) being chased down by a pack of cultists who tie him down and cut off his hand in a shot that demonstrates, vividly, that the filmmakers are more concerned with the idea of appalling gore than with halfway-decent effects work. This turns out to be a certain Dubois, as we'll only learn after his death is discovered by the members of the archaeological dig he's been working with: expedition leader Sir Giles Dalrymple (Jack Gwillim), John Bray (Ronald Howard), and Dubois's daughter and Bray's ladyfriend Annette (Jeanne Roland, with a hellacious overdubbed French accent). They're all very sad at this tragedy, for about three seconds, after which time they get back to celebrating their new discovery, the tomb of Ra-Antef, lost son of Ramses VIII. Two other people show up with a special interest in the treasures and beautifully-preserved mummy in this tomb: Hashmi Bey (George Pastell), offering a huge sum of money to keep the findings in the Cairo Museum, and spectacularly crass American Alexander King (Fred Clark), the dig's financier, for whom even a huge sum of money isn't enough; he wants a daft and perverse sum of money, and he's going to get it by putting together an Egyptian roadshow themed around the curse of the tomb, charging people ten cents to risk the wrath of the ancient pharaohs, correctly assuming that audiences would adore that kind of hokey spookiness.

The first stop is in England, and on the ship there, an amateur Egyptologist by the name of Adam Beauchamp (Terence Morgan) finds the team, impressing them with his rather inexplicable knowledge of their find, and seducing Annette right out from under Bray's nose. This tepid little romantic triangle is just a blind though, for Beauchamp has darker secrets, involving an amulet whose purpose none of the archaeologists have been able to figure out, though we in the audience, still waiting for something that even vaguely resembles a killer mummy by the time the film enters its back half, possess a pretty clear sense of what the amulet does, and what Beauchamp wants to do with it, if not exactly why.

The final 15 minutes of The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb have the real merit of being batshit crazy, if nothing else, so I have to respect that about the movie - any time that a twist ending so ballsy and stupid is whipped out with so little apology, the screenwriter has my undivided attention, if not necessarily my respect. It's especially welcome in this film, coming as it does after over an hour of the most tedious wrangling of characters and too much plot (a huckster American showman trying to put together a mummy cabaret is one thing, and I'm already not sure it's the right thing for a Hammer film; but presenting the entirety of his floor show is absolutely deadening). Even by the standards of a Hammer film with all the reliable stock company members left out, the acting is dreadful: Morgan makes for an especially uncompelling romantic foil/secret villain, and even without taking the dubbing into account, Roland's boggle-eyed overreacting, in her feature film debut (and the only big role she ever had), puts her high in the running for worst female lead in any Hammer film ever, and that is a singularly competitive race. Ronald Howard comes across well just for being unmemorable. I suppose Clark's broad Ugly American routine is amusing enough, though mostly because he has personality, and very little else does.

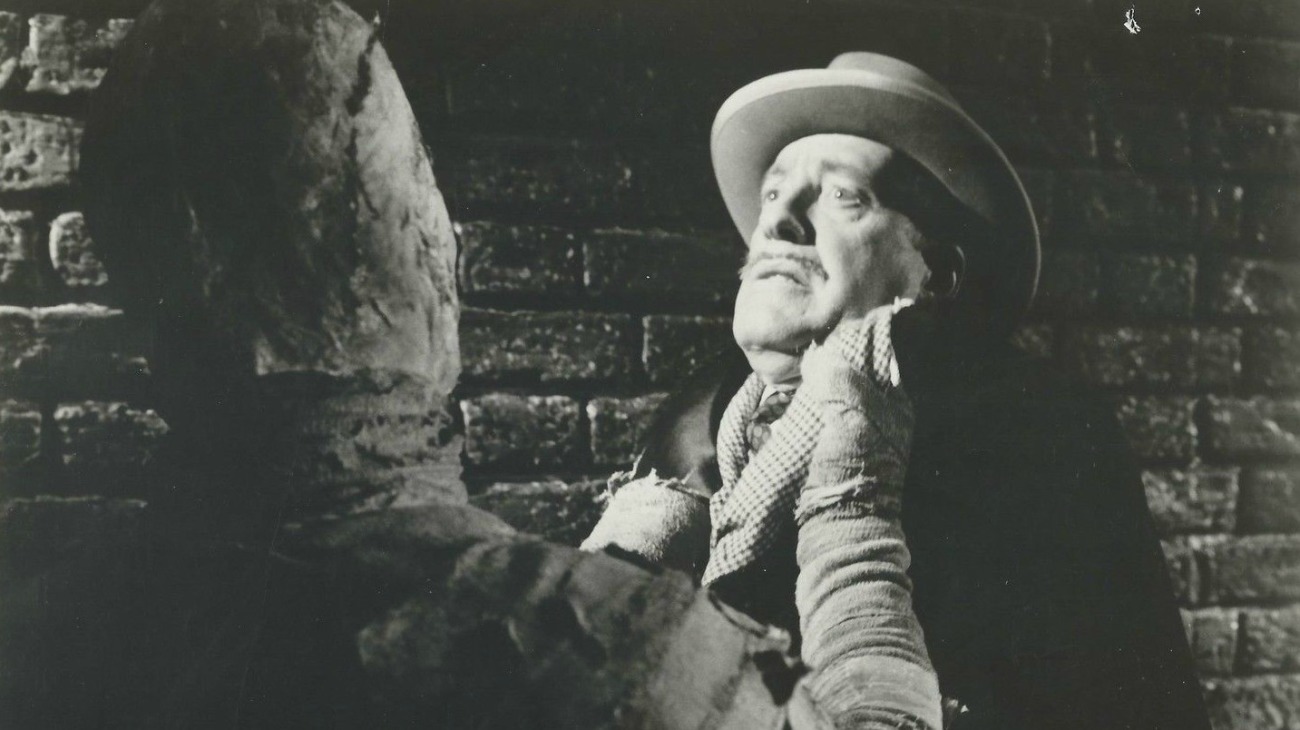

The worst thing, though, is probably the mummy, played by Dickie Owen, combining the cheap production values with poor acting and unmotivated storytelling to create a perfect crystallisation of everything wrong with the film. It's an especially stupid-looking make-up job, like a papier-mâché mask without breathing holes and only the most rudimentary eye holes; the monster is accompanied by a rasping, Darth Vader-esque breathing noise on the soundtrack that is the exact opposite of scary; the killing scenes are awkwardly staged with no eye towards emphasising the mummy's menace or strength. It's not a remotely credible threat, and with so much misfiring in The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb, the absence of even a satisfyingly creepy mummy is an absolute film-killing flaw.

Reviews in this series

The Mummy (Fisher, 1959)

The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb (Carreras, 1964)

The Mummy's Shroud (Gilling, 1967)

Blood from the Mummy's Tomb (Holt and Carreras, 1971)

For the really, incredibly obvious thing about The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb, as becomes obvious from the instant the opening credits start up, is that it is cheap as all hell. Those credits take place over a single long take of the camera moving across a pile of ancient riches taken from (presumably) a mummy's tomb, and between the flat lighting and the quality of the props, there's no doubting at all that we're looking at plaster and plastic and desperation; there might not ever be a point in the rest of the film where that looks as patently artificial, but there's hardly anything that seriously challenges this first impression. And this is especially sad, because if there was one thing that made Hammer Films special from a production standpoint, it's the creative ways the directors and cinematographers found to hide the low budget. Just a year prior, Hammer had produced The Pirates of Blood River, a movie seemingly designed from the ground up to prove that you could make an exciting pirate film without having enough money to set any scenes onboard a ship.

And yet here's The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb, looking as tattered and chintzy as any Poverty Row film from the '40s. The indifferently-painted backdrops, the unconvincing make-up: this is, I think, what happens when you have people without training in making these kind of low-budget, atmosphere-driven horror films bear the weight fo making. For the problems, though they extend beyond the lighting, are always made worst because of the lighting, as though cinematographer Otto Heller had absolutely no clue how to deal with the emotional needs of the genre. Which, given the total absence of horror anywhere else in his filmography, is almost certainly the case.

For there is one of the other problems, surely the biggest single reason that this picture feels hardly at all like a Hammer film: it is hardly a Hammer film. For reasons that a sufficiently devoted researcher could undoubtedly scrounge up, if he was motivated for whatever reason to pretend that this film was worth the time, The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb wasn't shot at Hammer's home turf of Bray Studios, but at Elstree Studios, and almost entirely with people who lacked any previous experience with the production company. The most important Hammer veteran in the crew, in fact, was producer/director/writer Michael Carreras, son of the company's co-founder Sir James Carreras, and responsible for producing the lion's share of movies released during the company's best years. He was not, however, nearly as prolific a director, and there is not much of anything in this movie to suggest that this was a terrible loss to the corpus of British horror. It is a singularly tension-free movie that Carreras wrought; almost more interesting in being a mystery-slash-treasure hunt to bother being a thriller about a rampaging mummy.

The film opens in Egypt in 1900, in the company of a man (Bernard Rebel) being chased down by a pack of cultists who tie him down and cut off his hand in a shot that demonstrates, vividly, that the filmmakers are more concerned with the idea of appalling gore than with halfway-decent effects work. This turns out to be a certain Dubois, as we'll only learn after his death is discovered by the members of the archaeological dig he's been working with: expedition leader Sir Giles Dalrymple (Jack Gwillim), John Bray (Ronald Howard), and Dubois's daughter and Bray's ladyfriend Annette (Jeanne Roland, with a hellacious overdubbed French accent). They're all very sad at this tragedy, for about three seconds, after which time they get back to celebrating their new discovery, the tomb of Ra-Antef, lost son of Ramses VIII. Two other people show up with a special interest in the treasures and beautifully-preserved mummy in this tomb: Hashmi Bey (George Pastell), offering a huge sum of money to keep the findings in the Cairo Museum, and spectacularly crass American Alexander King (Fred Clark), the dig's financier, for whom even a huge sum of money isn't enough; he wants a daft and perverse sum of money, and he's going to get it by putting together an Egyptian roadshow themed around the curse of the tomb, charging people ten cents to risk the wrath of the ancient pharaohs, correctly assuming that audiences would adore that kind of hokey spookiness.

The first stop is in England, and on the ship there, an amateur Egyptologist by the name of Adam Beauchamp (Terence Morgan) finds the team, impressing them with his rather inexplicable knowledge of their find, and seducing Annette right out from under Bray's nose. This tepid little romantic triangle is just a blind though, for Beauchamp has darker secrets, involving an amulet whose purpose none of the archaeologists have been able to figure out, though we in the audience, still waiting for something that even vaguely resembles a killer mummy by the time the film enters its back half, possess a pretty clear sense of what the amulet does, and what Beauchamp wants to do with it, if not exactly why.

The final 15 minutes of The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb have the real merit of being batshit crazy, if nothing else, so I have to respect that about the movie - any time that a twist ending so ballsy and stupid is whipped out with so little apology, the screenwriter has my undivided attention, if not necessarily my respect. It's especially welcome in this film, coming as it does after over an hour of the most tedious wrangling of characters and too much plot (a huckster American showman trying to put together a mummy cabaret is one thing, and I'm already not sure it's the right thing for a Hammer film; but presenting the entirety of his floor show is absolutely deadening). Even by the standards of a Hammer film with all the reliable stock company members left out, the acting is dreadful: Morgan makes for an especially uncompelling romantic foil/secret villain, and even without taking the dubbing into account, Roland's boggle-eyed overreacting, in her feature film debut (and the only big role she ever had), puts her high in the running for worst female lead in any Hammer film ever, and that is a singularly competitive race. Ronald Howard comes across well just for being unmemorable. I suppose Clark's broad Ugly American routine is amusing enough, though mostly because he has personality, and very little else does.

The worst thing, though, is probably the mummy, played by Dickie Owen, combining the cheap production values with poor acting and unmotivated storytelling to create a perfect crystallisation of everything wrong with the film. It's an especially stupid-looking make-up job, like a papier-mâché mask without breathing holes and only the most rudimentary eye holes; the monster is accompanied by a rasping, Darth Vader-esque breathing noise on the soundtrack that is the exact opposite of scary; the killing scenes are awkwardly staged with no eye towards emphasising the mummy's menace or strength. It's not a remotely credible threat, and with so much misfiring in The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb, the absence of even a satisfyingly creepy mummy is an absolute film-killing flaw.

Reviews in this series

The Mummy (Fisher, 1959)

The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb (Carreras, 1964)

The Mummy's Shroud (Gilling, 1967)

Blood from the Mummy's Tomb (Holt and Carreras, 1971)

Categories: british cinema, hammer films, horror, mummies, needless sequels