So hurty it funs

I think that it is easiest to begin with a statement that is probably objectively true: you will like Aqua Teen Hunger Force Colon Movie Film for Theaters if you liked the parent series; and the more you like that show, the more you will like the feature.

To go any further is the get caught very quickly in the thickets of personal taste, and the thorny matter of surrealism. Or absurdism. Or both. This is hardly surprising; surrealism is a hallmark of the Adult Swim cartoon family (of which the series ATHF is a founding member) in general, and the Williams Street studios in particular.

This isn't Adult Swim, however; it's the multiplex, and that makes the experience of watching ATHFCMFFT (I promise not to do that again) very, very different from the series: it is perhaps more rewarding and unquestionably much harder.

There's no way around this simple fact: 11 minutes is much shorter than 86 minutes. A single episode of the show is something like a hit-and-run assault of free-form lunacy; the audience is quite ravaged by the experience, but it's over almost as soon as it's begun. There's not really much chance to ponder how bizarre the concept and execution are during the episode, only after it's finished. The movie is altogether a different beast: after a little while, it becomes quite impossible to just go along for the ride and one inevitably begins to think about what the hell is going on.

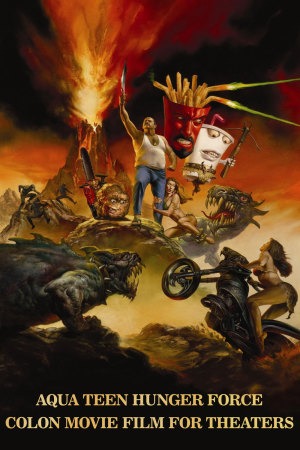

What the hell is going on, for the tragically uninitiated, is this: a milkshake named Master Shake, a hovering box of fries named Frylock and a meatball named Meatwad all live together in a dingy New Jersey suburban home, next door to the ill-tempered Carl Brutananadilewski, occasionally troubling themselves to save the world. In the particular case of this film, they are pitted against an unspeakably ancient and evil piece of exercise equipment, whose creation and purpose are mysteriously tied in with the half-dozen or so origin stories for the Aqua Teens themselves. That's really giving the plot more emphasis than it deserves. The film, as the series, is more properly regarded as a series of ephemeral gags ranging from the pop-cultural-satirical to the scatological, and often to the flat-out absurd.

On television, this comes off as...well, not "normal," but maybe something like "normalized." After all, TV is an inherently surreal medium. I'm not at all the first person to point out what a strange thing it is to have this electronic box that shows eight minutes of a narrative program followed by three minutes of thirty-second short films. Mighty tomes have been written on the nature of television's "flow," and I only differ from the majority in that I view this as an unambiguously undesirable state of things.

Compared to novels and movies and plays, television doesn't make a lick of goddamn sense. Most of us have been trained since birth to decode the medium, and I suspect that most of us are pretty good at ignoring the advertisements completely. Then again, there is the matter of TiVo, blessed be its name, which draws close to turning all television into the premium cable ideal of the uninterrupted program.

The point, though, is that TV is still a medium of profound fluidity, tiny units running one into the other. In this way, the stream-of-consciousness surrealism of Aqua Teen Hunger Force is the most natural thing in the world, a ten-minute distillation of the whole TV experience. It doesn't stand out as being unusually "weird" in a formal sense.

The movie is a different beast altogether. In general, the cinematic flow is self-contained and ordered; in most non-experimental films every moment is designed to be seen in the context of every other moment. There is a very narrow history of films that subscribe to the ATHF model of eschewing narrative completely in favor of a string of disconnected gags and incidents. Even the Monty Python films, for all that they are skits strung on a throughline, are more rigorously plotted than this. Frankly, the ATHF feature is the most pure surrealism I've ever seen in the English-language cinema: its precursors are the films of Luis Buñuel, if anything.

In other words, while the series stands out because of its content, the movie stands out because of its structure, and returning to what I said earlier, the audience has more of a chance to reflect on this because of the film's duration. In practical terms, this means that there's a long stretch in the middle where there isn't a whole lot of laughing going on. It's not because the movie isn't funny, per se. It's more like an experience I had once when trying to watch every episode of Monty Python's Flying Circus (the high water mark of televised surrealism): there came a point when I was tired of laughing, and I began responding to the goings-on with a very clinical, detached consideration of "ah, that is funny," and breaking down in my mind the reasons why. It took the Pythons some 12 hours to put me in that state; Maiellaro and Willis get the job done in thirty minutes.

The film is very, very funny; and it is very, very exhausting. I am extremely grateful that it's not any longer than 86 minutes. I feel I should go back to where I began: if you like the show, you will like the film. There is no meaningful difference between the types of jokes, although the film does occasionally play with the "epic" quality of a movie versus a TV episode in moments like the early title card, "Ancient Egypt, Thousands of Years Ago, 3 PM, 1492, New York," or the literally breathtaking opening sequence, which I will not spoil save to say that I haven't laughed with such fulfillment at a movie in a long time.

Nor will I spoil anything else. Honestly, it's not that hard to figure out if this is your cup of tea or not. If you think you'll like it, you almost certainly will.

8/10

To go any further is the get caught very quickly in the thickets of personal taste, and the thorny matter of surrealism. Or absurdism. Or both. This is hardly surprising; surrealism is a hallmark of the Adult Swim cartoon family (of which the series ATHF is a founding member) in general, and the Williams Street studios in particular.

This isn't Adult Swim, however; it's the multiplex, and that makes the experience of watching ATHFCMFFT (I promise not to do that again) very, very different from the series: it is perhaps more rewarding and unquestionably much harder.

There's no way around this simple fact: 11 minutes is much shorter than 86 minutes. A single episode of the show is something like a hit-and-run assault of free-form lunacy; the audience is quite ravaged by the experience, but it's over almost as soon as it's begun. There's not really much chance to ponder how bizarre the concept and execution are during the episode, only after it's finished. The movie is altogether a different beast: after a little while, it becomes quite impossible to just go along for the ride and one inevitably begins to think about what the hell is going on.

What the hell is going on, for the tragically uninitiated, is this: a milkshake named Master Shake, a hovering box of fries named Frylock and a meatball named Meatwad all live together in a dingy New Jersey suburban home, next door to the ill-tempered Carl Brutananadilewski, occasionally troubling themselves to save the world. In the particular case of this film, they are pitted against an unspeakably ancient and evil piece of exercise equipment, whose creation and purpose are mysteriously tied in with the half-dozen or so origin stories for the Aqua Teens themselves. That's really giving the plot more emphasis than it deserves. The film, as the series, is more properly regarded as a series of ephemeral gags ranging from the pop-cultural-satirical to the scatological, and often to the flat-out absurd.

On television, this comes off as...well, not "normal," but maybe something like "normalized." After all, TV is an inherently surreal medium. I'm not at all the first person to point out what a strange thing it is to have this electronic box that shows eight minutes of a narrative program followed by three minutes of thirty-second short films. Mighty tomes have been written on the nature of television's "flow," and I only differ from the majority in that I view this as an unambiguously undesirable state of things.

Compared to novels and movies and plays, television doesn't make a lick of goddamn sense. Most of us have been trained since birth to decode the medium, and I suspect that most of us are pretty good at ignoring the advertisements completely. Then again, there is the matter of TiVo, blessed be its name, which draws close to turning all television into the premium cable ideal of the uninterrupted program.

The point, though, is that TV is still a medium of profound fluidity, tiny units running one into the other. In this way, the stream-of-consciousness surrealism of Aqua Teen Hunger Force is the most natural thing in the world, a ten-minute distillation of the whole TV experience. It doesn't stand out as being unusually "weird" in a formal sense.

The movie is a different beast altogether. In general, the cinematic flow is self-contained and ordered; in most non-experimental films every moment is designed to be seen in the context of every other moment. There is a very narrow history of films that subscribe to the ATHF model of eschewing narrative completely in favor of a string of disconnected gags and incidents. Even the Monty Python films, for all that they are skits strung on a throughline, are more rigorously plotted than this. Frankly, the ATHF feature is the most pure surrealism I've ever seen in the English-language cinema: its precursors are the films of Luis Buñuel, if anything.

In other words, while the series stands out because of its content, the movie stands out because of its structure, and returning to what I said earlier, the audience has more of a chance to reflect on this because of the film's duration. In practical terms, this means that there's a long stretch in the middle where there isn't a whole lot of laughing going on. It's not because the movie isn't funny, per se. It's more like an experience I had once when trying to watch every episode of Monty Python's Flying Circus (the high water mark of televised surrealism): there came a point when I was tired of laughing, and I began responding to the goings-on with a very clinical, detached consideration of "ah, that is funny," and breaking down in my mind the reasons why. It took the Pythons some 12 hours to put me in that state; Maiellaro and Willis get the job done in thirty minutes.

The film is very, very funny; and it is very, very exhausting. I am extremely grateful that it's not any longer than 86 minutes. I feel I should go back to where I began: if you like the show, you will like the film. There is no meaningful difference between the types of jokes, although the film does occasionally play with the "epic" quality of a movie versus a TV episode in moments like the early title card, "Ancient Egypt, Thousands of Years Ago, 3 PM, 1492, New York," or the literally breathtaking opening sequence, which I will not spoil save to say that I haven't laughed with such fulfillment at a movie in a long time.

Nor will I spoil anything else. Honestly, it's not that hard to figure out if this is your cup of tea or not. If you think you'll like it, you almost certainly will.

8/10

Categories: animation, avant-garde, comedies