The triumphant farewell of the zombie crusaders

Precious few film series can sustain a fourth entry. And when there's already been a constant drop in quality from one movie to the next, it's pretty much impossible to regard the idea of yet one more go-round with anything but minor dread; perhaps revulsion or dismissal, but not anything positive.

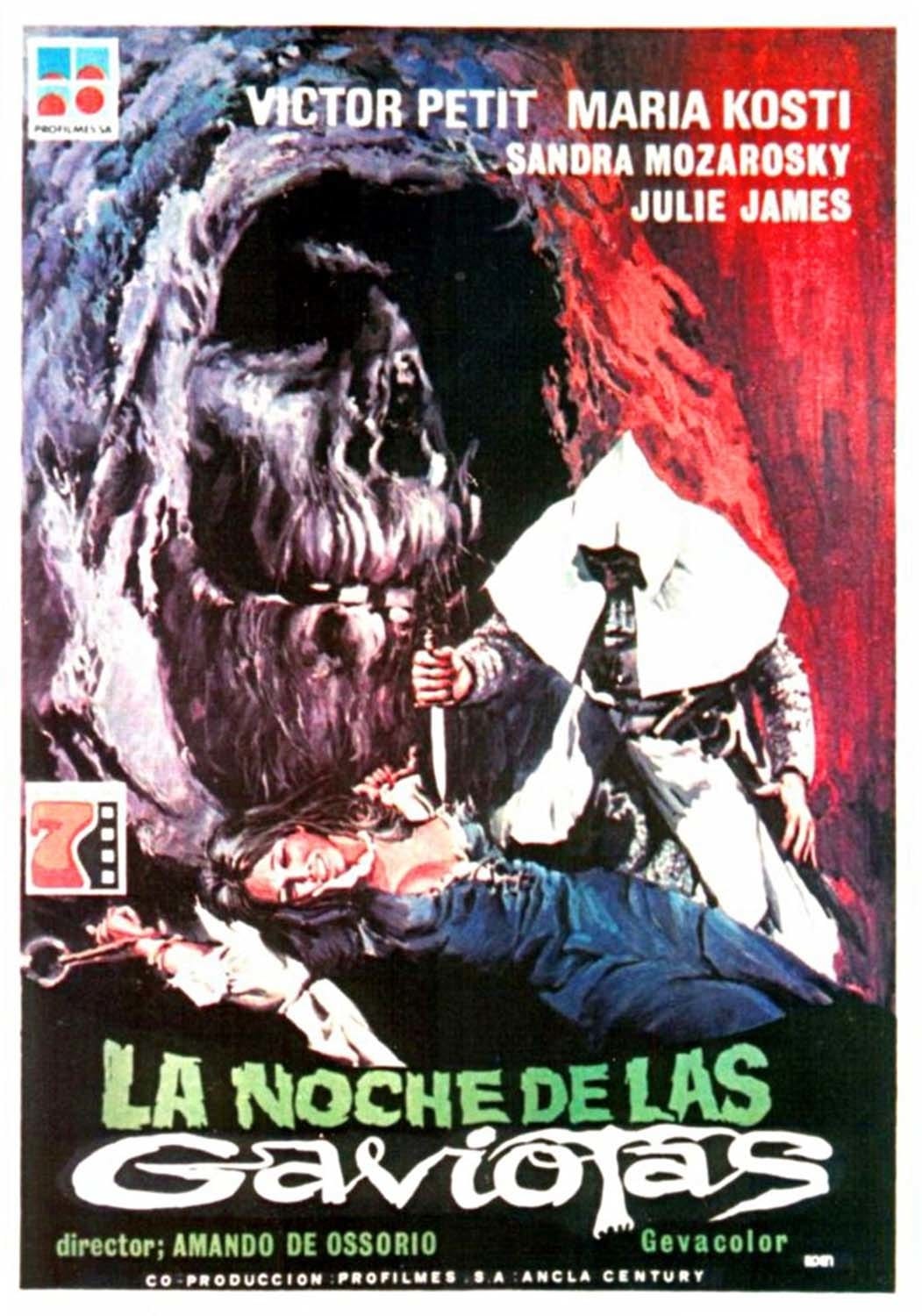

Rules being made to be broken, it's only somewhat surprising that Amando de Ossorio's fourth and final Blind Dead film, Night of the Seagulls, should be one of these rare and privileged fourth films that not only clearly trounces it dreadful predecessor The Ghost Galleon, and easily surpasses the first sequel, Return of the Evil Dead; and topping it all off, it's almost as good as the wonderful Tombs of the Blind Dead itself, and if I can't exactly say that Seagulls is the best of all the Blind Dead pictures, it is nevertheless the best in certain respects. Not bad for the third sequel in a European zombie franchise from the mid-1970s.

Like the original film, unlike the second, and like the third tried and desperately failed to achieve, the chief success of Seagulls is in generating a sustained mood of almost unbearable creepiness, "creepy" being a much-appreciated but sadly rare quality for a horror film. Most of the time, horror filmmakers would go sooner for suspense, or better yet for terror (though real terror is as common in cinema as a unicorn is in Manhattan); failing that, the bulk of them find solace in baroque gore effects. But creepiness is the best thing about horror; creepiness is the prickly feeling on your neck, the sense of hovering danger you get when the heroes have gone in the rickety old house and seen the painting of the angry man with red eyes, but haven't actually been chased by the ghost yet. Creepiness is the time when you don't know what's scary yet, but you know that something is wrong, and so there's no brake on your imagination from visualising whatever you please. What makes Ossorio a genius - if not a genius in some global sense of cinematic genius, he's damn certainly a genius in horror - is that he can sustain that exact feeling even after we've already seen the Blind Dead in his movies, even after people have died and we expect more to die in the same way. In Seagulls, he can even keep that feeling up for more than an hour out of an 88 minute feature, despite giving away the game in the opening scene and, by all appearances, taking it for granted that everybody in the audience has already seen the other three films by now.

The action opens in the 14th Century, or thereabouts, with a young couple (acted by two performers whose names I could not tell you with any comfortable certainty) journeying to a small town in the country, and getting themselves lost. He goes on head to figure out what's happening, and she stays behind, in the gathering fog, watching as a line of men in white robes ride on the road beneath the bluff she's standing on. There's nothing I can write to explain how, exactly this all works, because it is deeply visual: but it is so damned moody and atmospheric - yeah, I finally used the word, my apologies - that you just know something bad is on the outskirts, and yet there's no fear, just a pronounced uneasiness. Of course, we in the audience are very aware of exactly what something is going to be bad, so when the men in white kill the man and abduct the woman, it's less shocking and more routine. But! having shown young topless virgins getting sacrificed in three movies now, Ossorio switches things up a touch. The ceremony itself is presented in a much more stylised manner, without nearly so much blood, but a great deal more solemnity. There's a small idol of some kind of ancient fish god watching, and in the scene's eeriest touch, the dead woman (played, obviously, by a plastic stand-in) is left as food for damp, shiny crabs the size of a dinner plate, that advance towards her body in a series of shots that goes on for a whole lot longer than you'd expect a horror film to allot for such an apparently minor detail. But that's Ossorio's gift: made to choose between what is efficient narrative and what is evocative and poetically terrifying, he selects the latter, every time. Nothing "happens" for the 40 seconds that the crabs scuttle down the rocks, and yet it is one of the most piercing, memorable images in Seagulls.

From their, the action hops to the present day (of 1975), though I cannot say precisely where in Europe we are. One character is surnamed "Flanagan", and reference is made to this film's version of the undead Templars having come over from France centuries earlier, which at least loosely suggests that we're on the British Isles, though that seems like a really strange change after three films in or around Portugal. At any rate, we have another young couple, Dr. Henry Stein (Victor Petit) and his wife Joan (María Kosty), newly come to an isolated town on the coast where Henry intends to practise medicine. It's one of those standard-issue horror story towns full of locals who all know the same secret but won't share it, and weird traditions that the outsider protagonists witness by accident, that seem to have no good reason to exist, and the odd inexplicable event that nobody else seems to notice, familiar from the work of H.P. Lovecraft to mid-period Friday the 13th entries, but in this particular case I am most reminded of the 1973 British horror masterwork The Wicker Man. I'm not sure why: maybe because the protagonists are kind of supercilious, maybe because the unspoken threat seems to be uncanny and weird rather than physically dangerous (which is of course not the case).

I'm not going to spend any more time on the plot, since it doesn't really matter very much to the final product; what matters is that for quite a while Henry and Joan witness one thing after another that they don't understand or willfully misinterpret, and the great bulk of those things are suffused with that characteristic Ossorio creepiness I was raving about up above. Women go missing, black-robed people march on the beach chanting, and seagulls scream in the night sky, even though seagulls aren't supposed to be out at night. The creation of atmosphere for the second act of the movie is magnificent, and quite beyond my skills to describe it. Things fall apart a bit in the end, as it turns once again into a post-Romero "we are in a house, surrounded by zombies" thriller, although to Ossorio's credit he never allows the film to be more about its plot than about its tone.

I said that Seagulls was in certain respects better than Tombs; and I stick by that. For one thing, this film undoubtedly uses music better than the others, a strange thing to say given how much music overlaps between the four movies. I think it has a lot to do with the line between diegetic music (appears in the world of the film, so that the characters can hear it) and non-diegetic music (only the audience can hear it), has been muddled a lot, though not erased completely.

The Blind Dead themselves also look at their very best in this entry, and we see a lot of them in nearly full light, so they certainly had every reason to fail. Everything about the way the zombie knights are portrayed in Seagulls is actually unique for the series: having concluded that after three pictures, we understand the whole damn backstory, Ossorio no longer presents them as a novel threat, full of mystery and terror. But at the same moment, he's able to use our familiarity with the Blind Dead against us, for while we know them as the creepy skeleton guys who hover about ruined places, the image of them standing on a beach in bright light (the day-for-night in this film is magnificently unconvincing, and I think it's by intent - adds to the uncanniness) isn't just unnerving because there's a skeleton in a robe on the beach, it's unnerving because wait, can the Blind Dead do that?

Beyond all that, this just feels different, not like a zombie movie at all, more like a nightmare put to film. The biggest threat isn't the Blind Dead, it's the off-kilter world that they've created and are a part of, and what makes this perhaps my favorite of the series (though I'd have to admit that Tombs is the "best") is that the whole thing feels almost like it mixes zombie horror with Surrealism. Nothing is "right" in the little seaside town, and the fact that there's a cabal of 600-year-old blood drinking Templars is just kind of part of that - exactly contrary to the usual notion that horror is about the weird and terrifying making its way into a normal, safe space. Somehow, despite having a boilerplate plot, generic characters, and villains making their fourth appearance in as many years, Night of the Seagulls feels unlike any other horror movie I've ever seen, and if that's not the sign of Ossorio's ultimate genius in creating this franchise, I can't think of what would be.

Reviews in this series

Tombs of the Blind Dead (de Ossorio, 1971)

Return of the Evil Dead (de Ossorio, 1973)

The Ghost Galleon (de Ossorio, 1974)

Night of the Seagulls (de Ossorio, 1975)

Rules being made to be broken, it's only somewhat surprising that Amando de Ossorio's fourth and final Blind Dead film, Night of the Seagulls, should be one of these rare and privileged fourth films that not only clearly trounces it dreadful predecessor The Ghost Galleon, and easily surpasses the first sequel, Return of the Evil Dead; and topping it all off, it's almost as good as the wonderful Tombs of the Blind Dead itself, and if I can't exactly say that Seagulls is the best of all the Blind Dead pictures, it is nevertheless the best in certain respects. Not bad for the third sequel in a European zombie franchise from the mid-1970s.

Like the original film, unlike the second, and like the third tried and desperately failed to achieve, the chief success of Seagulls is in generating a sustained mood of almost unbearable creepiness, "creepy" being a much-appreciated but sadly rare quality for a horror film. Most of the time, horror filmmakers would go sooner for suspense, or better yet for terror (though real terror is as common in cinema as a unicorn is in Manhattan); failing that, the bulk of them find solace in baroque gore effects. But creepiness is the best thing about horror; creepiness is the prickly feeling on your neck, the sense of hovering danger you get when the heroes have gone in the rickety old house and seen the painting of the angry man with red eyes, but haven't actually been chased by the ghost yet. Creepiness is the time when you don't know what's scary yet, but you know that something is wrong, and so there's no brake on your imagination from visualising whatever you please. What makes Ossorio a genius - if not a genius in some global sense of cinematic genius, he's damn certainly a genius in horror - is that he can sustain that exact feeling even after we've already seen the Blind Dead in his movies, even after people have died and we expect more to die in the same way. In Seagulls, he can even keep that feeling up for more than an hour out of an 88 minute feature, despite giving away the game in the opening scene and, by all appearances, taking it for granted that everybody in the audience has already seen the other three films by now.

The action opens in the 14th Century, or thereabouts, with a young couple (acted by two performers whose names I could not tell you with any comfortable certainty) journeying to a small town in the country, and getting themselves lost. He goes on head to figure out what's happening, and she stays behind, in the gathering fog, watching as a line of men in white robes ride on the road beneath the bluff she's standing on. There's nothing I can write to explain how, exactly this all works, because it is deeply visual: but it is so damned moody and atmospheric - yeah, I finally used the word, my apologies - that you just know something bad is on the outskirts, and yet there's no fear, just a pronounced uneasiness. Of course, we in the audience are very aware of exactly what something is going to be bad, so when the men in white kill the man and abduct the woman, it's less shocking and more routine. But! having shown young topless virgins getting sacrificed in three movies now, Ossorio switches things up a touch. The ceremony itself is presented in a much more stylised manner, without nearly so much blood, but a great deal more solemnity. There's a small idol of some kind of ancient fish god watching, and in the scene's eeriest touch, the dead woman (played, obviously, by a plastic stand-in) is left as food for damp, shiny crabs the size of a dinner plate, that advance towards her body in a series of shots that goes on for a whole lot longer than you'd expect a horror film to allot for such an apparently minor detail. But that's Ossorio's gift: made to choose between what is efficient narrative and what is evocative and poetically terrifying, he selects the latter, every time. Nothing "happens" for the 40 seconds that the crabs scuttle down the rocks, and yet it is one of the most piercing, memorable images in Seagulls.

From their, the action hops to the present day (of 1975), though I cannot say precisely where in Europe we are. One character is surnamed "Flanagan", and reference is made to this film's version of the undead Templars having come over from France centuries earlier, which at least loosely suggests that we're on the British Isles, though that seems like a really strange change after three films in or around Portugal. At any rate, we have another young couple, Dr. Henry Stein (Victor Petit) and his wife Joan (María Kosty), newly come to an isolated town on the coast where Henry intends to practise medicine. It's one of those standard-issue horror story towns full of locals who all know the same secret but won't share it, and weird traditions that the outsider protagonists witness by accident, that seem to have no good reason to exist, and the odd inexplicable event that nobody else seems to notice, familiar from the work of H.P. Lovecraft to mid-period Friday the 13th entries, but in this particular case I am most reminded of the 1973 British horror masterwork The Wicker Man. I'm not sure why: maybe because the protagonists are kind of supercilious, maybe because the unspoken threat seems to be uncanny and weird rather than physically dangerous (which is of course not the case).

I'm not going to spend any more time on the plot, since it doesn't really matter very much to the final product; what matters is that for quite a while Henry and Joan witness one thing after another that they don't understand or willfully misinterpret, and the great bulk of those things are suffused with that characteristic Ossorio creepiness I was raving about up above. Women go missing, black-robed people march on the beach chanting, and seagulls scream in the night sky, even though seagulls aren't supposed to be out at night. The creation of atmosphere for the second act of the movie is magnificent, and quite beyond my skills to describe it. Things fall apart a bit in the end, as it turns once again into a post-Romero "we are in a house, surrounded by zombies" thriller, although to Ossorio's credit he never allows the film to be more about its plot than about its tone.

I said that Seagulls was in certain respects better than Tombs; and I stick by that. For one thing, this film undoubtedly uses music better than the others, a strange thing to say given how much music overlaps between the four movies. I think it has a lot to do with the line between diegetic music (appears in the world of the film, so that the characters can hear it) and non-diegetic music (only the audience can hear it), has been muddled a lot, though not erased completely.

The Blind Dead themselves also look at their very best in this entry, and we see a lot of them in nearly full light, so they certainly had every reason to fail. Everything about the way the zombie knights are portrayed in Seagulls is actually unique for the series: having concluded that after three pictures, we understand the whole damn backstory, Ossorio no longer presents them as a novel threat, full of mystery and terror. But at the same moment, he's able to use our familiarity with the Blind Dead against us, for while we know them as the creepy skeleton guys who hover about ruined places, the image of them standing on a beach in bright light (the day-for-night in this film is magnificently unconvincing, and I think it's by intent - adds to the uncanniness) isn't just unnerving because there's a skeleton in a robe on the beach, it's unnerving because wait, can the Blind Dead do that?

Beyond all that, this just feels different, not like a zombie movie at all, more like a nightmare put to film. The biggest threat isn't the Blind Dead, it's the off-kilter world that they've created and are a part of, and what makes this perhaps my favorite of the series (though I'd have to admit that Tombs is the "best") is that the whole thing feels almost like it mixes zombie horror with Surrealism. Nothing is "right" in the little seaside town, and the fact that there's a cabal of 600-year-old blood drinking Templars is just kind of part of that - exactly contrary to the usual notion that horror is about the weird and terrifying making its way into a normal, safe space. Somehow, despite having a boilerplate plot, generic characters, and villains making their fourth appearance in as many years, Night of the Seagulls feels unlike any other horror movie I've ever seen, and if that's not the sign of Ossorio's ultimate genius in creating this franchise, I can't think of what would be.

Reviews in this series

Tombs of the Blind Dead (de Ossorio, 1971)

Return of the Evil Dead (de Ossorio, 1973)

The Ghost Galleon (de Ossorio, 1974)

Night of the Seagulls (de Ossorio, 1975)