Greed monster

A review requested by Caleb, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

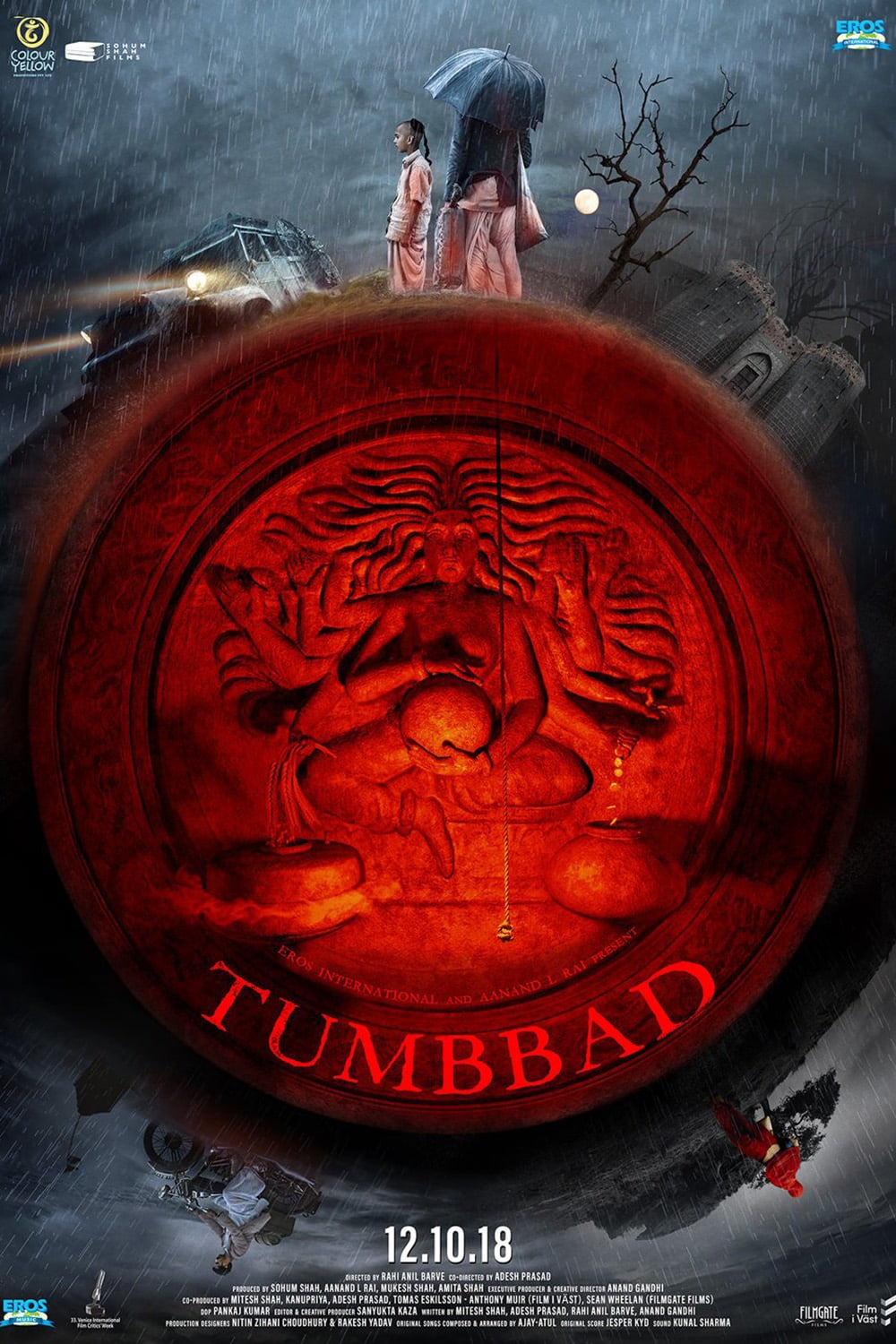

The 2018 Hindi-language horror movie Tumbbad, we are told, originated in 1993, when director and co-writer Rahi Anil Barve was around 14 years old, and listened in rapt horror as a friend told him a story based in the Marathi-language horror short stories of the writer Narayan Dharap. Barve was so unnerved by the story that turning it into a movie basically became his life's work after that; he wrote the first draft of the screenplay in 1997, almost got it into production in 2008, succeeded in getting it shot in 2012 but decided that what he had didn't match what was in his head, so he scrapped a lot of it and re-shot much of it in 2015, after which he spent over two years in post-production tinkering with it. And when it came out in the fall of 2018, it was immediately greeted as an unusual novelty in Hindi- and English-language press in its native India, to say nothing of the novelty it was received with elsewhere in the world, where the very notion of "Hindi horror" was basically a complete unknown before. This is the story that the film has been packaged with ever since it began its journey outside of South Asia; it's the kind of story you want to feel good about getting behind, the kind of story that has you rooting for a movie before you even know what it is.

But it's not really a useful story. The useful part comes in the form of a single errant detail buried deep in the story, when Barve spoke about his experience revisiting the Dharap story in preparation for actually making the movie: he didn't like it. What he liked, he found, was the circumstances under which he'd heard the story, at night in a forest, with his friend's vivid narration bringing it to life. And that, I think, explains the singular, wonderful vibe of Tumbbad, a film whose script (by Barve, Mitesh Shah, "creative director" Adesh Prasad, and co-diretor Anand Gandhi) is kind of clunky and malformed and extremely hard to make sense of in the first third if you don't already know what's going on, but results in a beautifully gripping horror movie anyway. Because it's not really about the clarity about the script, but about the mood it expresses, a mood that Barve and cinematographer Pankaj Kumar drench it with thanks to their aggressively dark, shadow-soaked images. It's a ghost story, explicitly in the form of its slightly opaque framing narrative, but also in the way that you sort of ride along top of it; I have now seen the film twice and I absolutely could not tell you how every single scene leads into the subsequent scene, nor would I want to. The film creeps into your bones and gives you a little shiver of discomfort at how very unknowable the world is, out there in the dark, how you never can be quite certain there's nothing waiting to devour you.

Flattening things out a bit and doing some of the work of solving the film's narrative puzzles, we have here a three-part structure, in which Vinayak (Sohum Shah) tells his teenage son Pandurang (Mohammad Samad) about the secrets of an abandoned mansion in the cursed town of Tumbbad, where it always rains. At the dawn of the universe, it seems, the Goddess of Prosperity gave birth to all of the gods. The firstborn, Hastar, was greedy to keep all of her gold and food to himself, but he was defeated by the rest of the gods, and the Goddess of Prosperity saved his life only by agreeing that he would never be worshiped and never be spoken of. And so things went, until a shrine was built to Hastar at Tumbbad, the site where Hastar remains trapped and slumbering in his mother's womb. And this brings us to Vinayak's days as a boy (Dhundiraj Prabhakar Jogalekar), when he lived in Tumbbad, and when his mother (Jyoti Malshe) worked for the local lord (Madhav Hari Joshi), who was the guardian of Hastar's treasure.

What follows is a three-part story concerning Vinayak as a child, a young man, and a father, and how he encountered the mansion and Hastar's prison at each of those stages of life, and the corruption it caused within him. The film could not possibly be more blatant in its intentions that we understand this as a 104-minute fable about the corrosive impact of greed - it opens with a Mahatma Gandhi quote to that effect, a swaggering appeal to authority that the remainder of Tumbbad never even pretends to earn - and I guess it's fair to say that's the takeaway theme, as much as anything else is. But I really don't think that viewing Tumbbad in terms of "themes", or even in terms of "what happens in the story" gets us very far: this is a movie all about a mood. That mood is, to be fair, directly connected to the themes, in that it's a mood about corruption, ruination, suffering, all of those good things. But if it were just "greed is bad, and Vinayak would have been better off not being greedy", there wouldn't really be a movie here. Where the movie resides is in the heavy, airless atmosphere that Barve and company place over the entire film. I mean, just to pull at one tiny thing, the fact that it's always raining or on the brink of raining in Tumbbad. That's a terrific detail: it advances the plot and literalises the idea that the Hastar shrine has put a shroud over the town, and it just feels. Not feels anything in particular. Just that, as you're watching it, you feel the wet, feel the chill, feel the grey-toned colors as a kind of clammy, smothered feeling.

This goes even more for the scenes set indoors, away from the rain. I don't know how Kumar figured out a way to shoot an entire movie with such limited lighting (one major scene was apparently lit with nothing but an oil lamp), but the upshot of his aggressive rejection of lightbulbs is that Tumbbad is one of the most aggressively black horror movies I have seen. Not in the "sculpting with shadows" way that a film from the Val Lewton production unit in the '40s is black, as much as I love that kind of look. This is a primordial black, one that seems to carve itself out of the images rather than function within them. That's where so much of the campfire mood comes from: that sense that we are not fully seeing "into" the movie, that something about it is so putrescently evil that it couldn't even register on the camera's light sensors, like a vampire not showing up in a mirror. It is a movie of the unknown, the unknowable, the hiding-in-the-dark. And that's true long before it actually literally becomes about the horrible demon (Harsh K.) hiding in the dark. Truth be told, we actually get a pretty good look at him, and the repugnantly fleshy space in which he has been imprisoned. And I do love the parts of Tumbbad that go into Hastar's subterranean womb-space: they are tremendously gory and visceral, caking everything in raw, red wetness, lighting Harsh K. to emphasise the little shark teeth that are the most unnerving part of his generally unnerving makeup. When Tumbbad goes for horrific violence, it goes all the way, and these scenes, which are carefully distributed to punctuate the first two thirds of the film before screaming through the last third, are probably the most legitimately horrifying in the movie.

Which is part of the strength of the film: it can be both disgustingly horrifying, but also more subdued and gloomy and ethereal, and these two modes end up complimenting each other. The black and red hell scenes hit harder for ripping there way into all of the damp murk of the film leading up to them; the damp and murky parts feel all the more oppressive for feeling like an extension of the hell scenes. It's quite beautifully balanced.

Mostly. The film has two big shortcomings, one that it can't really be blamed for. That one is the atrocious CGI, which unfortunately is what the film elects to lead with: the story of the Goddess of Prosperity and Hastar's punishment that opens the film is rendered in computer animated imagery that might have passed muster as a cut scene in a video game around 2003 or 2004, but looks horribly weightless and smooth for anything in a feature film, let alone one from as late in the game as 2018. But I get that we're dealing with a low-budget Indian film, and allowances must be made; I just wished that the film didn't start by demanding that we make those allowances. The good news is that it means that the film gets its worst scene out of the way early, and when more CGI shows up later, it's generally used better: not that it looks better, but Barve is able to take advantage of the slick anti-reality of the effects and create an uncanny mood with them.

The other shortcoming, the one that throws the movie out of balance, is that the film has a problem with its middle. The opening act, with Little Vinayak starting to grasp the terrors of a subterranean, nighttime world of inhuman horrors, is excellent. The closing act, with Papa Vinayak and Pandurang finding that they are not remotely clever enough to outthink those horrors, is a wild blast of gruesome imagery. The middle act is where Tumbbad actually does most of its storytelling and character building and sermonising about greed, and it's... okay. Some great, great images. But also some boring patches. It's mostly for this reason that I would make the claim that this is a "mood" movie more than "story" movie; because when it is more focused on its story, it kind of starts to drag. The cut we have is around half the length of the assembly cut, but I frankly think it could have been cut tighter still.

Granting that, if one-third of a movie is going to be meaningfully weaker than the other two, the middle third is the one you want it to be: it means that the film roars out of the gate and screams to a close, right up to its extremely bleak and sad and ugly ending. So it slows down there a bit; that's a small price to pay for something that has as many treasures as Tumbbad does - to say nothing of how unique it is. I am no expert on Indian cinema, but the people who are experts on Indian cinema seem to think that this mode of oppressive atmosphere and brutal imagery don't really happen there, and while that mode isn't unfamiliar to American and European horror cinema, the Hindu cosmology that permeates every part of this scenario is much less familiar. The combination ends up creating a feeling of permeability between the world of humans and the world of ancient horrors that I can't really compare to anything else, and it's a feeling that makes Tumbbad an exceptionally fascinating and disorienting experience.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

The 2018 Hindi-language horror movie Tumbbad, we are told, originated in 1993, when director and co-writer Rahi Anil Barve was around 14 years old, and listened in rapt horror as a friend told him a story based in the Marathi-language horror short stories of the writer Narayan Dharap. Barve was so unnerved by the story that turning it into a movie basically became his life's work after that; he wrote the first draft of the screenplay in 1997, almost got it into production in 2008, succeeded in getting it shot in 2012 but decided that what he had didn't match what was in his head, so he scrapped a lot of it and re-shot much of it in 2015, after which he spent over two years in post-production tinkering with it. And when it came out in the fall of 2018, it was immediately greeted as an unusual novelty in Hindi- and English-language press in its native India, to say nothing of the novelty it was received with elsewhere in the world, where the very notion of "Hindi horror" was basically a complete unknown before. This is the story that the film has been packaged with ever since it began its journey outside of South Asia; it's the kind of story you want to feel good about getting behind, the kind of story that has you rooting for a movie before you even know what it is.

But it's not really a useful story. The useful part comes in the form of a single errant detail buried deep in the story, when Barve spoke about his experience revisiting the Dharap story in preparation for actually making the movie: he didn't like it. What he liked, he found, was the circumstances under which he'd heard the story, at night in a forest, with his friend's vivid narration bringing it to life. And that, I think, explains the singular, wonderful vibe of Tumbbad, a film whose script (by Barve, Mitesh Shah, "creative director" Adesh Prasad, and co-diretor Anand Gandhi) is kind of clunky and malformed and extremely hard to make sense of in the first third if you don't already know what's going on, but results in a beautifully gripping horror movie anyway. Because it's not really about the clarity about the script, but about the mood it expresses, a mood that Barve and cinematographer Pankaj Kumar drench it with thanks to their aggressively dark, shadow-soaked images. It's a ghost story, explicitly in the form of its slightly opaque framing narrative, but also in the way that you sort of ride along top of it; I have now seen the film twice and I absolutely could not tell you how every single scene leads into the subsequent scene, nor would I want to. The film creeps into your bones and gives you a little shiver of discomfort at how very unknowable the world is, out there in the dark, how you never can be quite certain there's nothing waiting to devour you.

Flattening things out a bit and doing some of the work of solving the film's narrative puzzles, we have here a three-part structure, in which Vinayak (Sohum Shah) tells his teenage son Pandurang (Mohammad Samad) about the secrets of an abandoned mansion in the cursed town of Tumbbad, where it always rains. At the dawn of the universe, it seems, the Goddess of Prosperity gave birth to all of the gods. The firstborn, Hastar, was greedy to keep all of her gold and food to himself, but he was defeated by the rest of the gods, and the Goddess of Prosperity saved his life only by agreeing that he would never be worshiped and never be spoken of. And so things went, until a shrine was built to Hastar at Tumbbad, the site where Hastar remains trapped and slumbering in his mother's womb. And this brings us to Vinayak's days as a boy (Dhundiraj Prabhakar Jogalekar), when he lived in Tumbbad, and when his mother (Jyoti Malshe) worked for the local lord (Madhav Hari Joshi), who was the guardian of Hastar's treasure.

What follows is a three-part story concerning Vinayak as a child, a young man, and a father, and how he encountered the mansion and Hastar's prison at each of those stages of life, and the corruption it caused within him. The film could not possibly be more blatant in its intentions that we understand this as a 104-minute fable about the corrosive impact of greed - it opens with a Mahatma Gandhi quote to that effect, a swaggering appeal to authority that the remainder of Tumbbad never even pretends to earn - and I guess it's fair to say that's the takeaway theme, as much as anything else is. But I really don't think that viewing Tumbbad in terms of "themes", or even in terms of "what happens in the story" gets us very far: this is a movie all about a mood. That mood is, to be fair, directly connected to the themes, in that it's a mood about corruption, ruination, suffering, all of those good things. But if it were just "greed is bad, and Vinayak would have been better off not being greedy", there wouldn't really be a movie here. Where the movie resides is in the heavy, airless atmosphere that Barve and company place over the entire film. I mean, just to pull at one tiny thing, the fact that it's always raining or on the brink of raining in Tumbbad. That's a terrific detail: it advances the plot and literalises the idea that the Hastar shrine has put a shroud over the town, and it just feels. Not feels anything in particular. Just that, as you're watching it, you feel the wet, feel the chill, feel the grey-toned colors as a kind of clammy, smothered feeling.

This goes even more for the scenes set indoors, away from the rain. I don't know how Kumar figured out a way to shoot an entire movie with such limited lighting (one major scene was apparently lit with nothing but an oil lamp), but the upshot of his aggressive rejection of lightbulbs is that Tumbbad is one of the most aggressively black horror movies I have seen. Not in the "sculpting with shadows" way that a film from the Val Lewton production unit in the '40s is black, as much as I love that kind of look. This is a primordial black, one that seems to carve itself out of the images rather than function within them. That's where so much of the campfire mood comes from: that sense that we are not fully seeing "into" the movie, that something about it is so putrescently evil that it couldn't even register on the camera's light sensors, like a vampire not showing up in a mirror. It is a movie of the unknown, the unknowable, the hiding-in-the-dark. And that's true long before it actually literally becomes about the horrible demon (Harsh K.) hiding in the dark. Truth be told, we actually get a pretty good look at him, and the repugnantly fleshy space in which he has been imprisoned. And I do love the parts of Tumbbad that go into Hastar's subterranean womb-space: they are tremendously gory and visceral, caking everything in raw, red wetness, lighting Harsh K. to emphasise the little shark teeth that are the most unnerving part of his generally unnerving makeup. When Tumbbad goes for horrific violence, it goes all the way, and these scenes, which are carefully distributed to punctuate the first two thirds of the film before screaming through the last third, are probably the most legitimately horrifying in the movie.

Which is part of the strength of the film: it can be both disgustingly horrifying, but also more subdued and gloomy and ethereal, and these two modes end up complimenting each other. The black and red hell scenes hit harder for ripping there way into all of the damp murk of the film leading up to them; the damp and murky parts feel all the more oppressive for feeling like an extension of the hell scenes. It's quite beautifully balanced.

Mostly. The film has two big shortcomings, one that it can't really be blamed for. That one is the atrocious CGI, which unfortunately is what the film elects to lead with: the story of the Goddess of Prosperity and Hastar's punishment that opens the film is rendered in computer animated imagery that might have passed muster as a cut scene in a video game around 2003 or 2004, but looks horribly weightless and smooth for anything in a feature film, let alone one from as late in the game as 2018. But I get that we're dealing with a low-budget Indian film, and allowances must be made; I just wished that the film didn't start by demanding that we make those allowances. The good news is that it means that the film gets its worst scene out of the way early, and when more CGI shows up later, it's generally used better: not that it looks better, but Barve is able to take advantage of the slick anti-reality of the effects and create an uncanny mood with them.

The other shortcoming, the one that throws the movie out of balance, is that the film has a problem with its middle. The opening act, with Little Vinayak starting to grasp the terrors of a subterranean, nighttime world of inhuman horrors, is excellent. The closing act, with Papa Vinayak and Pandurang finding that they are not remotely clever enough to outthink those horrors, is a wild blast of gruesome imagery. The middle act is where Tumbbad actually does most of its storytelling and character building and sermonising about greed, and it's... okay. Some great, great images. But also some boring patches. It's mostly for this reason that I would make the claim that this is a "mood" movie more than "story" movie; because when it is more focused on its story, it kind of starts to drag. The cut we have is around half the length of the assembly cut, but I frankly think it could have been cut tighter still.

Granting that, if one-third of a movie is going to be meaningfully weaker than the other two, the middle third is the one you want it to be: it means that the film roars out of the gate and screams to a close, right up to its extremely bleak and sad and ugly ending. So it slows down there a bit; that's a small price to pay for something that has as many treasures as Tumbbad does - to say nothing of how unique it is. I am no expert on Indian cinema, but the people who are experts on Indian cinema seem to think that this mode of oppressive atmosphere and brutal imagery don't really happen there, and while that mode isn't unfamiliar to American and European horror cinema, the Hindu cosmology that permeates every part of this scenario is much less familiar. The combination ends up creating a feeling of permeability between the world of humans and the world of ancient horrors that I can't really compare to anything else, and it's a feeling that makes Tumbbad an exceptionally fascinating and disorienting experience.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Categories: horror, indian cinema, the sopranos, violence and gore