Civil service

I think it goes without saying that the best answer to the question, "what do you would the right way to remake Kurosawa Akira's gorgeous 1952 melodrama Ikiru?" would be "I hope you die in a fire", but setting that aside, Living is actually pretty good. The biggest problem with it, by far, is that it's a remake of Ikiru, and how goddamn dare they. And not just "it adapts the story of Ikiru, which was anyway already an uncredited riff on Tolstoy's 1886 novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich", but it recreates Ikiru in some very explicit detail, including but not limited to the earlier film's startling and very exciting structural breach midway through, and restaging its most iconic shot exactly, including the weather conditions, with the only difference being the addition (barely) of color, and the fact that Living is in a wider aspect ratio (it's some very strange bespoke ratio that's wider than 1.37:1 and narrower than 1.66:1, and I have no idea what the point of it is - any insights would be welcome).

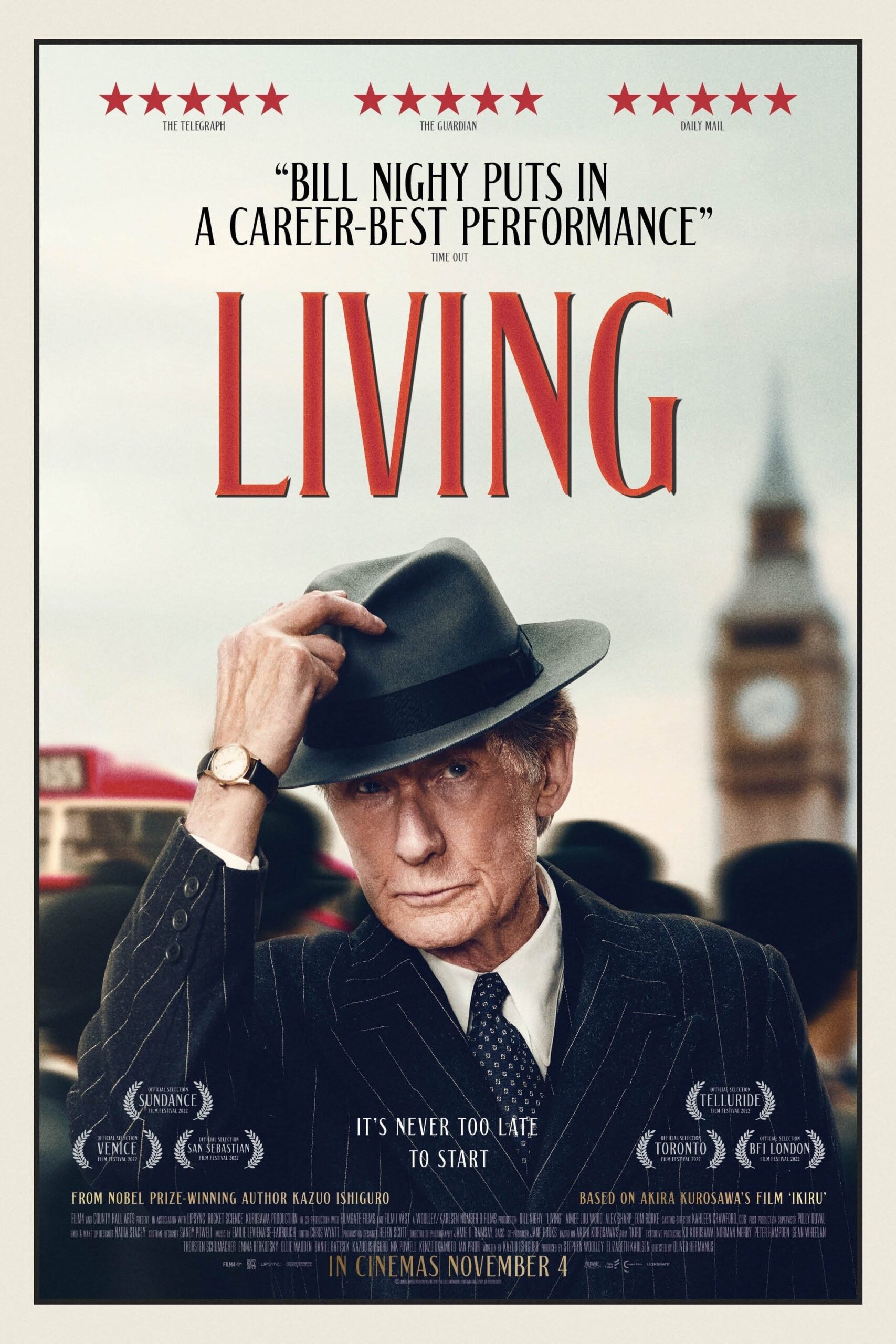

Conceding that, and what remains is a very, very lovely film, quiet and small and thoughtful about its profound and cosmic subject, no less than the proper way to use this indescribable gift we have all been given called "life". It comes from an honest place: celebrated novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, writing only his third screenplay (and one of those was for Guy Maddin's The Saddest Music in the World, which barely counts), has apparently been daydreaming for years about how much he wanted there to be a remake of Ikiru starring Bill Nighy in the Shimura Takashi role of an emotionally desiccated civil servant who is shocked to find that he has a human soul and a desire to bring joy and warmth and goodness into the world, as a result of being given a terminal cancer diagnosis. One chance meeting with Nighy later, and that is exactly what exists, and congratulations to Ishiguro on two very keen insights: the first is that Nighy would excel in this role. I think you could persuade me that he has given here the single best performance of any film released in 2022; it's beyond question to me that he's given the best performance nominated for the Oscar for Lead Actor. It's not even one of those "the performance makes the movie" deals, since Living is actually doing quite a lot that I think is quite admirable and successful, but it would certainly be easy to talk about it in those terms. He's setting a tone that the movie matches, and when it occasionally falters, mostly due to an iffy sense of pacing, he's there to keep it strapped together through his impeccably low-volume, no-frills performance, a work of subdued minimalism so precise and perfect that it almost feels maximalist.

And we'll get back to that, but I mentioned that Ishiguro had two insights, and the other one is that the particulars of this story are superbly well-suited to the culture and social conditions of England in the wake of the Second World War (it takes place in 1953, by which point Ikiru already existed, though not to my knowledge in the West). His work relocating the drama is so convincing that I actually sort of forgot, for the duration of its 102 minutes, that not only could this take place in a different context, I have in fact seen it in a different context. The post-war setting is critical: not right after the war, long enough that it's firmly in the past, but recent enough that the country is still in a state of disrepair and there's a sense of moral obligation to try and make sure it gets rebuilt better than it was before the bombing; and also far enough that a generation of young adults who are ready to begin this strange new thing called "midcentury culture" are starting to show up. The Englishness is critical: not all that many countries have exactly the right sort of civil bureaucracy to produce a figure like Williams, Nighy's character, an expert paper-pusher who has refined "bury this in an insoluble mountain of red tape" into something like a religious ritual. And it's a country that has, stereotypically at least, and certainly for that generation, encouraged a degree of emotional mutedness that both makes Williams's astonishment at the discovery he could actually be afraid to die seem deeply honest, and makes his continued refusal to actual emote while going through a profound crisis seem plausible.

Within the framework Ishiguro has provided, Living works very well, even excelling in some ways. If Ikiru is fundamentally melodramatic, albeit in a realist mode, Living is much more about a subdued vibe, one clearly derived from the kind of person its protagonist is, but not yoked to him subjectively. From the very first frames, which attempt (and mostly succeed) to create a period-feeling opening credits sequence, the movie presents itself as an aged document from many decades past, something that has been worn out and not preserved very well. Jamie Ramsay's cinematography captures a look of watery colors and fuzzy lighting, looking like film stock that wasn't stored correctly and was restored indifferently: it looks unusual and interesting and the colors are striking, but it's not pretty at all. It's a vision of 1953 through a veneer of historical curiosity, something forgotten by most and not really "loved" even by few, so much as treated with a kind of admiration that it's made it to us even in this battered state. Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch's score has an overly-sugared romanticism that exactly captures the feel of old instrumental popular music that absolutely does not afford being called "pop", the sort that middle-class people who wanted to feel classy but viewed intellectualism as pretentious and snobby listened to in the '50s. Sandy Powell's costumes exactly suggest the mostly-but-not-entirely conservative choices of pattern, color and line of people who want to look "neat" without calling attention to themselves, and also the way that a certain breed of English men seem to view smart, anonymous suits as something like a military uniform or suit of armor worn to do battle in the great war of Being Correct every day. All of this sums up to a remarkably coherent and intoxicating portrait of a specific place and time and attitude that could birth a man like Williams, and I will say this for director Oliver Hermanus: he has done a marvelous job of making sure that the people working on this film are proceeding in lockstep with each other, aligning every part of the film's visual aesthetic towards creating a feeling of muted, threadbare despair surrounded by a stubborn sort of vitalism that keeps trying to poke out even though it's not really working. A perfect match for our protagonist, in other words. And I continue to hold this admiration even as I think that Hermanus himself is a weak link: the compositions that aren't stolen from Kurosawa (one of the most accomplished composers of images in the history of the moving image) are a bit flat, the pacing too prone to stalling out.

The work in front of the camera is as good as the work in front of it. Living has done a wonderful job of assembling a whole cast full of people who look interesting enough to catch your eye from the moment you spot them, and then proceed to deepen our sense of their characters more and more every time we see them. The most attention is given to Aimee Lou Wood, playing a young woman whose overabundance of nervous energy makes her the closest thing for a lively person for Williams to latch onto in his desire to start living in the midst of dying, and while I think there are a couple of moments that feel like Wood is watching Nighy act more than her character is responding to his, she's mostly giving a very nice, lightly sad performance of a young person crawling towards the knowledge that old people can be sad and lonely and scared too. The rest of the cast is largely made up of people doing strong work in only a small number of scenes: Tom Burke makes a huge impression with a character who seems to exist almost entirely outside of the movie, and largely exists just to get to a scene where Nighy sings morbidly.

Living is, admittedly, Nighy's show, even more than Ikiru was Shimura's; not in the "we're abandoning this movie to the lead actor" way, but the much richer and more powerful, "we're going to trust the lead actor to do the work of tying this all together, forming the focal point for all of the movie's other tendencies". Nighy lives up to it and then some. It's a performance that feels very simple in a way, like there was really only one way it could have turned out, and he's making all of the obvious choices, but I think this is an artifact of how he made all of the correct choices, and then erased all of the work it took to get there. That is to say, everything here is mechanically precise: the way he speaks in a low register that's always perfectly articulated, never mumbled, except for when he very obviously had a reason for wanting to slur things a bit; the amount of brightness he lets into the performance at specific places; the way he plays his drunk scene as, fundamentally, an expression of his character's fatigue more than his character's abandon; his trick of raising his glance a moment before he actually starts to notice the person he's looking at or the thing he's reacting to. The performance is a very impressive mixture of the surprising - I never felt like I knew where Nighy was going to take a scene, especially the ones he shares with Wood - and the inevitable, making it seem impossible that Williams could be any other way than how we see him. It's nuanced character building that never calls attention to itself even as Living remains laser-focused on what Nighy is doing, and it results in some of the most delicate human storytelling that I have seen all year.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Conceding that, and what remains is a very, very lovely film, quiet and small and thoughtful about its profound and cosmic subject, no less than the proper way to use this indescribable gift we have all been given called "life". It comes from an honest place: celebrated novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, writing only his third screenplay (and one of those was for Guy Maddin's The Saddest Music in the World, which barely counts), has apparently been daydreaming for years about how much he wanted there to be a remake of Ikiru starring Bill Nighy in the Shimura Takashi role of an emotionally desiccated civil servant who is shocked to find that he has a human soul and a desire to bring joy and warmth and goodness into the world, as a result of being given a terminal cancer diagnosis. One chance meeting with Nighy later, and that is exactly what exists, and congratulations to Ishiguro on two very keen insights: the first is that Nighy would excel in this role. I think you could persuade me that he has given here the single best performance of any film released in 2022; it's beyond question to me that he's given the best performance nominated for the Oscar for Lead Actor. It's not even one of those "the performance makes the movie" deals, since Living is actually doing quite a lot that I think is quite admirable and successful, but it would certainly be easy to talk about it in those terms. He's setting a tone that the movie matches, and when it occasionally falters, mostly due to an iffy sense of pacing, he's there to keep it strapped together through his impeccably low-volume, no-frills performance, a work of subdued minimalism so precise and perfect that it almost feels maximalist.

And we'll get back to that, but I mentioned that Ishiguro had two insights, and the other one is that the particulars of this story are superbly well-suited to the culture and social conditions of England in the wake of the Second World War (it takes place in 1953, by which point Ikiru already existed, though not to my knowledge in the West). His work relocating the drama is so convincing that I actually sort of forgot, for the duration of its 102 minutes, that not only could this take place in a different context, I have in fact seen it in a different context. The post-war setting is critical: not right after the war, long enough that it's firmly in the past, but recent enough that the country is still in a state of disrepair and there's a sense of moral obligation to try and make sure it gets rebuilt better than it was before the bombing; and also far enough that a generation of young adults who are ready to begin this strange new thing called "midcentury culture" are starting to show up. The Englishness is critical: not all that many countries have exactly the right sort of civil bureaucracy to produce a figure like Williams, Nighy's character, an expert paper-pusher who has refined "bury this in an insoluble mountain of red tape" into something like a religious ritual. And it's a country that has, stereotypically at least, and certainly for that generation, encouraged a degree of emotional mutedness that both makes Williams's astonishment at the discovery he could actually be afraid to die seem deeply honest, and makes his continued refusal to actual emote while going through a profound crisis seem plausible.

Within the framework Ishiguro has provided, Living works very well, even excelling in some ways. If Ikiru is fundamentally melodramatic, albeit in a realist mode, Living is much more about a subdued vibe, one clearly derived from the kind of person its protagonist is, but not yoked to him subjectively. From the very first frames, which attempt (and mostly succeed) to create a period-feeling opening credits sequence, the movie presents itself as an aged document from many decades past, something that has been worn out and not preserved very well. Jamie Ramsay's cinematography captures a look of watery colors and fuzzy lighting, looking like film stock that wasn't stored correctly and was restored indifferently: it looks unusual and interesting and the colors are striking, but it's not pretty at all. It's a vision of 1953 through a veneer of historical curiosity, something forgotten by most and not really "loved" even by few, so much as treated with a kind of admiration that it's made it to us even in this battered state. Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch's score has an overly-sugared romanticism that exactly captures the feel of old instrumental popular music that absolutely does not afford being called "pop", the sort that middle-class people who wanted to feel classy but viewed intellectualism as pretentious and snobby listened to in the '50s. Sandy Powell's costumes exactly suggest the mostly-but-not-entirely conservative choices of pattern, color and line of people who want to look "neat" without calling attention to themselves, and also the way that a certain breed of English men seem to view smart, anonymous suits as something like a military uniform or suit of armor worn to do battle in the great war of Being Correct every day. All of this sums up to a remarkably coherent and intoxicating portrait of a specific place and time and attitude that could birth a man like Williams, and I will say this for director Oliver Hermanus: he has done a marvelous job of making sure that the people working on this film are proceeding in lockstep with each other, aligning every part of the film's visual aesthetic towards creating a feeling of muted, threadbare despair surrounded by a stubborn sort of vitalism that keeps trying to poke out even though it's not really working. A perfect match for our protagonist, in other words. And I continue to hold this admiration even as I think that Hermanus himself is a weak link: the compositions that aren't stolen from Kurosawa (one of the most accomplished composers of images in the history of the moving image) are a bit flat, the pacing too prone to stalling out.

The work in front of the camera is as good as the work in front of it. Living has done a wonderful job of assembling a whole cast full of people who look interesting enough to catch your eye from the moment you spot them, and then proceed to deepen our sense of their characters more and more every time we see them. The most attention is given to Aimee Lou Wood, playing a young woman whose overabundance of nervous energy makes her the closest thing for a lively person for Williams to latch onto in his desire to start living in the midst of dying, and while I think there are a couple of moments that feel like Wood is watching Nighy act more than her character is responding to his, she's mostly giving a very nice, lightly sad performance of a young person crawling towards the knowledge that old people can be sad and lonely and scared too. The rest of the cast is largely made up of people doing strong work in only a small number of scenes: Tom Burke makes a huge impression with a character who seems to exist almost entirely outside of the movie, and largely exists just to get to a scene where Nighy sings morbidly.

Living is, admittedly, Nighy's show, even more than Ikiru was Shimura's; not in the "we're abandoning this movie to the lead actor" way, but the much richer and more powerful, "we're going to trust the lead actor to do the work of tying this all together, forming the focal point for all of the movie's other tendencies". Nighy lives up to it and then some. It's a performance that feels very simple in a way, like there was really only one way it could have turned out, and he's making all of the obvious choices, but I think this is an artifact of how he made all of the correct choices, and then erased all of the work it took to get there. That is to say, everything here is mechanically precise: the way he speaks in a low register that's always perfectly articulated, never mumbled, except for when he very obviously had a reason for wanting to slur things a bit; the amount of brightness he lets into the performance at specific places; the way he plays his drunk scene as, fundamentally, an expression of his character's fatigue more than his character's abandon; his trick of raising his glance a moment before he actually starts to notice the person he's looking at or the thing he's reacting to. The performance is a very impressive mixture of the surprising - I never felt like I knew where Nighy was going to take a scene, especially the ones he shares with Wood - and the inevitable, making it seem impossible that Williams could be any other way than how we see him. It's nuanced character building that never calls attention to itself even as Living remains laser-focused on what Nighy is doing, and it results in some of the most delicate human storytelling that I have seen all year.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!