Your mother and mine

When a formidable artist makes a point of working away from all of his most overt strengths, it demands that we pay some especially close attention. I say this even though I'm not sure that Parallel Mothers quite counts as Pedro Almodóvar deliberately working away from his overt strengths. But I would be inclined to say that out of all his features I've seen, this is the one where I think I would have had the least chance of correctly identifying who directed it (outside of the gorgeous opening credits, always a strength in Almodóvar films). This isn't because Parallel Mothers is a failure, or beneath Almodóvar's talents, or any such thing, only that it is much more refined and restrained and prone to grounded emotions than I have expected from him. And, if I am being honest more than I want from him; we have so few filmmakers who are genuinely great at making profound art from tawdry excess, it feels a shame to lose one of them. And I do sort of think we're losing Almodóvar: this is his second consecutive feature, after 2019's Pain and Glory, that feels mostly sober and stately and reined-in, a polished and classy work of great talent and somewhat less gonzo ingenuity (in between them, he made a 30-minute gem of a short film, The Human Voice, that's much more my speed).

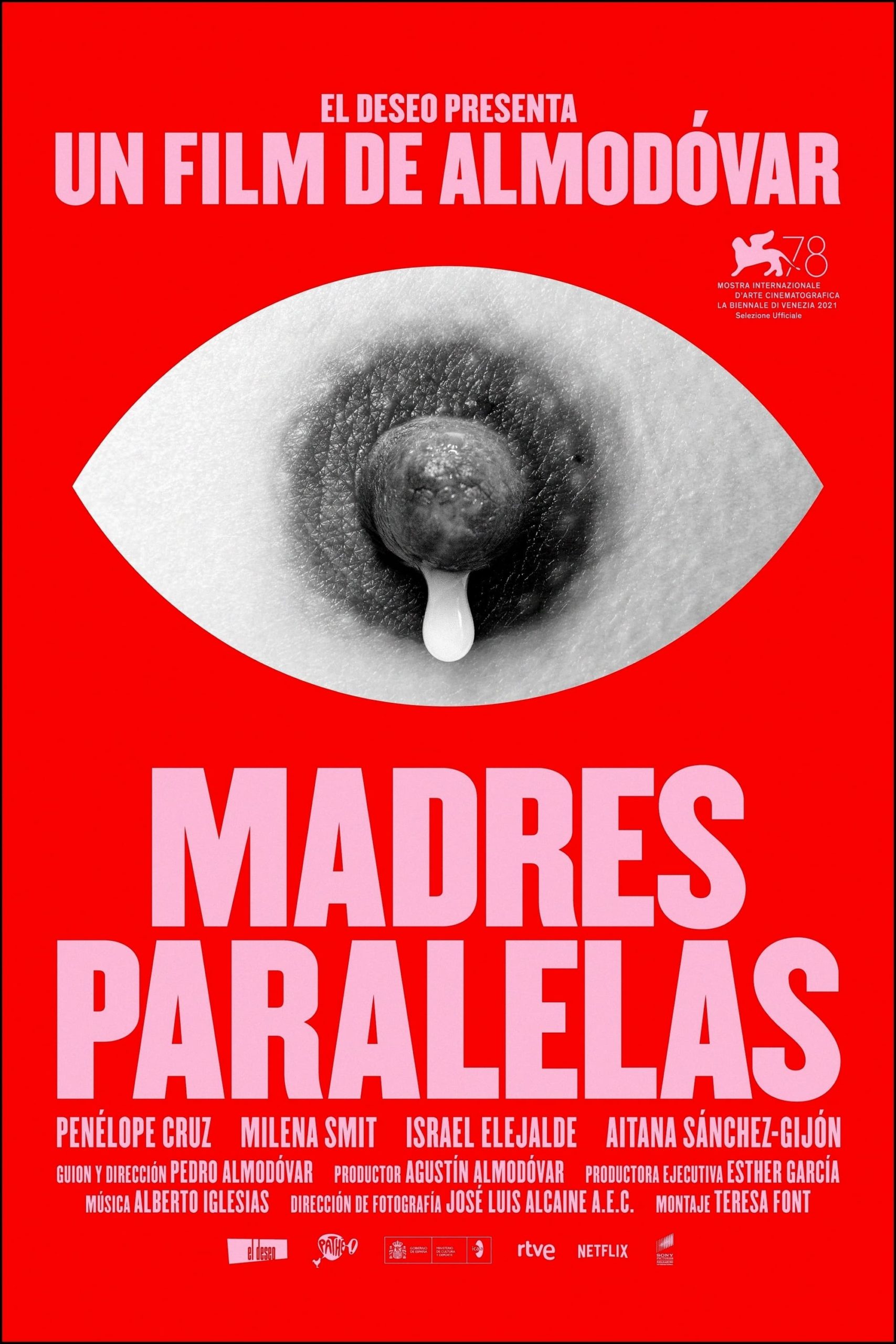

Rather than grouse about what the film isn't, though, I suppose it would be smart of me to start digging into what the film is. The filmmaker has been holding onto the story, or at least the title, of Parallel Mothers for over a decade (a fake poster for the film appears in his 2009 film Broken Embraces), and I do not know if he has been nurturing it for that whole time or if he just jotted down some ideas and walked away. I hope it wasn't the former; the script isn't that complex, and the one time it tries to add in complexity, it kind of muddies things up. Let us say, at any rate, that the film consists almost entirely of a muted melodramatic story about two women who have babies in the same hospital at the same time, and are roommates during this process and are, as you might say, mothers who are held in parallel by the film. The main mother is Janis Martinez, played by Almodóvar's recurring muse Penélope Cruz, and there's at least a strong possibility that this is the best work she's ever done onscreen, or at least it certainly asks her to make the most decisions and keep the most different aspects of her character afloat simultaneously. Janis is a photographer, which the film seems to think informs more of the action than I would argue it actually does (both the opening and closing credits are built around professional photography). Most of what we see her doing, in fact, is remaining very firmly in stasis, not able to make choices to move forwards or backwards. The other mother is the much younger Ana (Milena Smit), a teen with an emotionally inaccessible airhead actress for her own mother, Teresa (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón).

A melodrama, I said, and I don't see how you could possibly call it anything else, but a very tamped-down and grounded, human-scale melodrama it is. Without going into any sensitive plot material (one of the curious tricks that Parallel Mothers plays multiple times is to start flagging its twists a long time before they actually arrive, giving the film the feeling of a doomed tragedy more than an overheated soap opera. But twists they still are), I think it can be fairly said that the parallel mothers start to get entangled with each other, and in particular that Janis becomes consumed by uncertainty, doubt, guilt, and fear for the future, and to do something about these feelings - bury them? atone for them? revel in them by forcing herself to be constantly aware of them? - she doesn't so much take Ana under her wing as attempt to absorb the two of them into a single psychological entity.

Good, sturdy stuff, acted phenomenally well. Cruz and Smit are impeccable together and apart, and just because Almodóvar's script hands Cruz one complex, impossible moment after another, all gift-wrapped with possible reactions ready to go, that doesn't make it less impressive how cleanly Cruz assembles all of that into a cohesive portrait of a woman whose entire existence is based around her feeling of being internally incoherent.

The film built around these two actors is something that, upon reflection, something I'm not sure I've ever quite seen before, or imagined: an Almodóvar film that stays out of the way of the performances. Parallel Mothers is surely the most acting-forward film in the director's career, which is different than saying that his other movies have bad acting; some of them have in fact tremendously powerful acting. But I don't know if any of them were about the choices being made by the actors the way this is. Visually, this is a solid, clean, and shockingly plainspoken movie. It situates us in real spaces, inhabited by the women in the cast (there's only one man of importance; we'll get to him, but I do sort of wish the writer-director had seen fit to give us less of him) with small gestures, often limited just to the direction they're looking and when. This is a far cry from the way that older Almodóvar films surround the cast with borderline-surreal explosions of color and bright light into cosmopolitan spaces, forcing the characters to cope not just with their narrative, but the floating unreality of their world. And I get it, it's a valid strategy, well-executed. At a certain point, though, it feels like one has gotten in front of everything that Parallel Mothers plans to trot out, stylistically. Nor does that point come very late.

There's still plenty of bold plays in the storytelling, notably the loose and elliptical way that scenes have been placed next to each other, with the editing across scene breaks doing none of the things we expect to cue "time has now passed" (and in one moment, editor Teresa Font has very obviously made the choice to do the exact opposite, blending a flashback into the present so invisibly that our subsequent disorientation was very clearly "the point"). The film skips ahead months in the span of an eyeblink, creating a sense of an eternal, dreadfully precarious present, and it's a pretty startling, challenging way to build a story. But that challenge is involved with the characters, not just a bit of flashy formal play on its own terms.

So far, so good; not what I expected maybe, and honestly not really what I wanted, but you have to admire the execution. Then we come to the matter of the film's bookends. Janis, we learn immediately, has been working with a forensic archaeologist named Arturo (Israel Elejalde) to get the necessary permissions to exhume a mass grave where her great-grandfather and several other men from his rural village were buried, after having been executed by Nationalists during the Civil War. This is going to take months, maybe even years to put together, and Arturo and Janis sleep together multiple times during that process, and hence the pregnancy. It's immediately clear that this isn't just a pretext for getting Arturo in the picture: Almodóvar's filmography, especially early on, always dealt with the matter of Franco and his dictatorship by very actively not engaging with it, leaving a galling absence where "history" goes that defines 20th Century Spain specifically in disavowing it. For the director to make what I believe is his first-ever explicit reference to the war and Franco's thugs is no small gesture, and it's not forgotten anytime soon, even as the plot steadily remains elsewhere.

So there's definitely meant to be thematic overlap, and this is made even clearer as the resolution to the melodrama, at the far side of the movie's 123 minutes, fizzles apart while the exhumation comes back in full force for a coda that completely overrides all of the emotional arcs that appeared to have been in play. I say "appeared" because it's very obvious that we're meant to draw connections between the story of Janis and Ana, and the story of modern Spain's reckoning with its violent past, still less than a century old. Both stories pivot around questions of guilt and culpability, the need to mourn but the awareness that life is still ongoing, how we write our story in the present as a result of changes we wish we'd made differently or are proud of.

Just because I can intellectually grasp the connections Parallel Mothers wants me to make - and it does, definitely, want the viewer to make those connections, it is not at all looking to hold our hands here - doesn't quite make me feel like those connections are there, though. It's hard to say if the film is being too obvious or not obvious enough; if it's abandoning the reality of its plot for symoblism too readily, or if it would benefit from really just leaning into the Motherhood In Parallel imagery and not even pretend that these are real people in a real story. Whatever the right admixture is, I don't think it's the one the film landed on. Even more than my dismay that the film lacks color and visual ebullience, what really shocks me is that it doesn't have a pulse; Almodóvar's films have always been great at moving into the intellect through the viscera and loins, but this turns out to be almost a chilly intellectual exercise, coldly working through Thematic Undertones with philosophic detachment rather than gutsy conviction. And that is something that I really didn't expect and don't want, and it makes the whole movie rather less appealing than its accumulated strengths would suggest.

Rather than grouse about what the film isn't, though, I suppose it would be smart of me to start digging into what the film is. The filmmaker has been holding onto the story, or at least the title, of Parallel Mothers for over a decade (a fake poster for the film appears in his 2009 film Broken Embraces), and I do not know if he has been nurturing it for that whole time or if he just jotted down some ideas and walked away. I hope it wasn't the former; the script isn't that complex, and the one time it tries to add in complexity, it kind of muddies things up. Let us say, at any rate, that the film consists almost entirely of a muted melodramatic story about two women who have babies in the same hospital at the same time, and are roommates during this process and are, as you might say, mothers who are held in parallel by the film. The main mother is Janis Martinez, played by Almodóvar's recurring muse Penélope Cruz, and there's at least a strong possibility that this is the best work she's ever done onscreen, or at least it certainly asks her to make the most decisions and keep the most different aspects of her character afloat simultaneously. Janis is a photographer, which the film seems to think informs more of the action than I would argue it actually does (both the opening and closing credits are built around professional photography). Most of what we see her doing, in fact, is remaining very firmly in stasis, not able to make choices to move forwards or backwards. The other mother is the much younger Ana (Milena Smit), a teen with an emotionally inaccessible airhead actress for her own mother, Teresa (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón).

A melodrama, I said, and I don't see how you could possibly call it anything else, but a very tamped-down and grounded, human-scale melodrama it is. Without going into any sensitive plot material (one of the curious tricks that Parallel Mothers plays multiple times is to start flagging its twists a long time before they actually arrive, giving the film the feeling of a doomed tragedy more than an overheated soap opera. But twists they still are), I think it can be fairly said that the parallel mothers start to get entangled with each other, and in particular that Janis becomes consumed by uncertainty, doubt, guilt, and fear for the future, and to do something about these feelings - bury them? atone for them? revel in them by forcing herself to be constantly aware of them? - she doesn't so much take Ana under her wing as attempt to absorb the two of them into a single psychological entity.

Good, sturdy stuff, acted phenomenally well. Cruz and Smit are impeccable together and apart, and just because Almodóvar's script hands Cruz one complex, impossible moment after another, all gift-wrapped with possible reactions ready to go, that doesn't make it less impressive how cleanly Cruz assembles all of that into a cohesive portrait of a woman whose entire existence is based around her feeling of being internally incoherent.

The film built around these two actors is something that, upon reflection, something I'm not sure I've ever quite seen before, or imagined: an Almodóvar film that stays out of the way of the performances. Parallel Mothers is surely the most acting-forward film in the director's career, which is different than saying that his other movies have bad acting; some of them have in fact tremendously powerful acting. But I don't know if any of them were about the choices being made by the actors the way this is. Visually, this is a solid, clean, and shockingly plainspoken movie. It situates us in real spaces, inhabited by the women in the cast (there's only one man of importance; we'll get to him, but I do sort of wish the writer-director had seen fit to give us less of him) with small gestures, often limited just to the direction they're looking and when. This is a far cry from the way that older Almodóvar films surround the cast with borderline-surreal explosions of color and bright light into cosmopolitan spaces, forcing the characters to cope not just with their narrative, but the floating unreality of their world. And I get it, it's a valid strategy, well-executed. At a certain point, though, it feels like one has gotten in front of everything that Parallel Mothers plans to trot out, stylistically. Nor does that point come very late.

There's still plenty of bold plays in the storytelling, notably the loose and elliptical way that scenes have been placed next to each other, with the editing across scene breaks doing none of the things we expect to cue "time has now passed" (and in one moment, editor Teresa Font has very obviously made the choice to do the exact opposite, blending a flashback into the present so invisibly that our subsequent disorientation was very clearly "the point"). The film skips ahead months in the span of an eyeblink, creating a sense of an eternal, dreadfully precarious present, and it's a pretty startling, challenging way to build a story. But that challenge is involved with the characters, not just a bit of flashy formal play on its own terms.

So far, so good; not what I expected maybe, and honestly not really what I wanted, but you have to admire the execution. Then we come to the matter of the film's bookends. Janis, we learn immediately, has been working with a forensic archaeologist named Arturo (Israel Elejalde) to get the necessary permissions to exhume a mass grave where her great-grandfather and several other men from his rural village were buried, after having been executed by Nationalists during the Civil War. This is going to take months, maybe even years to put together, and Arturo and Janis sleep together multiple times during that process, and hence the pregnancy. It's immediately clear that this isn't just a pretext for getting Arturo in the picture: Almodóvar's filmography, especially early on, always dealt with the matter of Franco and his dictatorship by very actively not engaging with it, leaving a galling absence where "history" goes that defines 20th Century Spain specifically in disavowing it. For the director to make what I believe is his first-ever explicit reference to the war and Franco's thugs is no small gesture, and it's not forgotten anytime soon, even as the plot steadily remains elsewhere.

So there's definitely meant to be thematic overlap, and this is made even clearer as the resolution to the melodrama, at the far side of the movie's 123 minutes, fizzles apart while the exhumation comes back in full force for a coda that completely overrides all of the emotional arcs that appeared to have been in play. I say "appeared" because it's very obvious that we're meant to draw connections between the story of Janis and Ana, and the story of modern Spain's reckoning with its violent past, still less than a century old. Both stories pivot around questions of guilt and culpability, the need to mourn but the awareness that life is still ongoing, how we write our story in the present as a result of changes we wish we'd made differently or are proud of.

Just because I can intellectually grasp the connections Parallel Mothers wants me to make - and it does, definitely, want the viewer to make those connections, it is not at all looking to hold our hands here - doesn't quite make me feel like those connections are there, though. It's hard to say if the film is being too obvious or not obvious enough; if it's abandoning the reality of its plot for symoblism too readily, or if it would benefit from really just leaning into the Motherhood In Parallel imagery and not even pretend that these are real people in a real story. Whatever the right admixture is, I don't think it's the one the film landed on. Even more than my dismay that the film lacks color and visual ebullience, what really shocks me is that it doesn't have a pulse; Almodóvar's films have always been great at moving into the intellect through the viscera and loins, but this turns out to be almost a chilly intellectual exercise, coldly working through Thematic Undertones with philosophic detachment rather than gutsy conviction. And that is something that I really didn't expect and don't want, and it makes the whole movie rather less appealing than its accumulated strengths would suggest.

Categories: almodovar, domestic dramas, spanish cinema