Strange and bitter

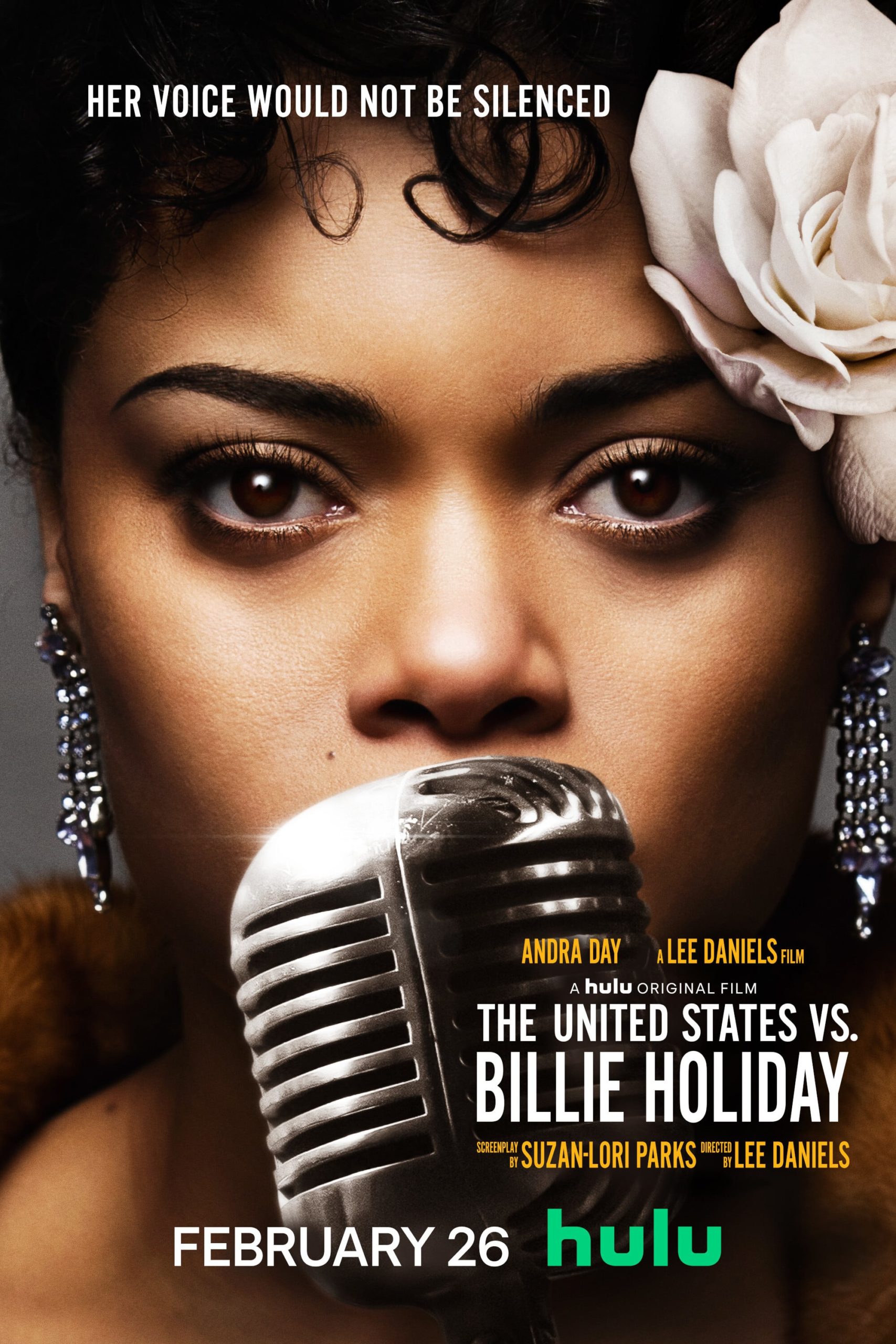

Anyone comfortable stating in public "I am a fan of the directorial works of Lee Daniels, and I root for his films to succeed" honestly deserves exactly what they get. But the thing is, I am a fan, and I do root for him; whatever one wants to say about his first three movies, 2005's Shadowboxer (which is alarmingly bad), 2009's Precious: Based on the Novel 'Push' by Sapphire (which is far too strange in its emphases and weird visionary elements to be written off as the Oscarbait it appears to be), and 2012's The Paperboy (which is magnificent trash of the most transcendent kind), they are all of them very confident about what they want to be, and hew to no obvious standards of aesthetic normality or human decency in getting to that point. They are bold, brash, unapologetic movie-movies. Unfortunately, his fourth feature, 2013's Lee Daniels' The Butler (there was a whole thing about the title) starts to get a little apologetic; one gets the sense that, after the somewhat inexplicable Oscar success of Precious, that Daniels thought it might be nice to actually court awards favor with a bland prestige film. And now, almost eight years later, during which time the director-producer has largely been toiling away in television, he's gone even further into the banal prestige trenches with The United States vs. Billie Holiday, a movie that's downright insipid in its sand-off-the edges attempt to do a nice biopic of a worthy subject, at the expense of having virtually any personality other than the one it can borrow from all the other nice biopics.

The hell of it is, it's not even good at that miserable little goal. Turns out that when you strip away most of the gaudiness that makes a Lee Daniels film what it is, you're left with some very slapdash, confused storytelling. We got that a little bit already with The Butler, but at least that had its grandiose scale. The United States vs. Billie Holiday doesn't even have that, by virtue of a plot that completely mangles the passage of time. It almost has the kind of bold-faced overheated melodrama that the director has found success with in the past, given that it feels sometimes like it has more scenes of the titular singer shooting up heroin than not shooting up heroin, but in order to make its political points, the film also can't sensationalise drug use. So instead of a messy epic about the tumultuous life of of an addict, the film simply yawns its way through scene after scene of substance abuse, with only two scenes in the film doing anything to meaningfully try to get at the subjective experience of using smack, and one of those isn't even centered on Billie Holiday herself.

So what do we have, anyway, if it's not melodrama, sensationalism, or grandiosity? Well, first we have Billie (played by pop singer-turned-movie star Andra Day, who took her stage name from Holiday's nickname "Lady Day") visiting an extravagant gnome-like white Southern radio host and hostile gay stereotype Reginald Lord Devine (Leslie Jordan) on his program, which triggers a flashback to her life, I guess? The relationship of the framework narrative to the rest of the movie is inconsistent and quickly forgotten. Anyway, Billie had, by the start of the 1940s, come to controversial national prominence over her recording of the anti-lynching song "Strange Fruit", and this freaked out the government, who were afraid that the song would trigger the civil rights movement. We know this because Suzan-Lori Parks's screenplay at one point has notorious FBI lawyer Roy Cohn (Damian Joseph Quinn) say the line "People are calling the song a starting gun for the so-called civil rights movement", which takes some extraordinary foresight on their part. Seriously, that is one for the bad biopic dialogue hall of fame if I ever I heard one.

The Feds have one idea for how to shut Billie and her dangerous, rabble-rousing song down: take advantage of her well-known drug problems, and just keep arresting her over and over again, planting drugs on her if there's no other way to do it. To this end, they plant a sexy turncoat, Jimmy Fletcher (Trevante Rhodes), in Billie's entourage, and he and his handler, Harry Anslinger (Garrett Hedlund) keep finding ways of harassing and threatening her. And that's, I think, the whole plot? If nothing else, The United States vs. Billie Holiday points out the difference between "eventful" and "dramatic": Billie Holiday live a very busy, chaotic life, but as a narrative, it pretty much just involves the same run-ins with the feds over and over again with almost no significant variation until we finally get to 1959 and the singer's premature death at 44.

This is just not very interesting to watch. Certainly not when it's stretched out to 130 minutes. The film's unmistakable secret weapon is Day, who physically resembles Holiday very little, but who has worked hard to ably re-create the singer's highly distinctive creaky voice, and on top of that has done much to capture her weary misery at being faced with all the bullshit of the world. A Golden Globe win is decidedly over-generous, but there's no denying that whatever human impact the story has is channeled through Day's stretched-thin facial expressions and anger-tinged line readings.She's not demanding our sympathy, allowing her Billie to be easily-annoyed and snappish, but this just makes her that much more appealing human as she oscillates between righteousness, fear, and put-upon pragmatism.

Not that The United States vs. Billie Holiday is giving her all that much to work with. The film's own conception of Billie is scattered, drawn up from various bits and bobs of her biography, including some hastily stuffed-in references to her affair with Tallulah Bankhead (Natasha Lyonne) that have absolutely no impact on anything. Thanks to this indistinct assemble of traits, coupled with the script's reluctance to seriously grapple with the negative impact of heroin usage, she basically doesn't emerge as a person with conflicts to work through, but just a rock around which the rest of the film flows.

Daniels directs this with a flat, trudge-through-the-events professionalism, only coming to life around the edges. The film has some very peculiar scene transitions in the form of quick little flickers of still images that abstractly call up the emotions that are at play, and this is at least unusual in a striking way, though the film never does this consistently. There's a hallucinatory sequence partway through that works terrifically well, blurring past and present in a kind of fuzzy, druggy haze, but the absence of any such trickery in the rest of the film is quite conspicuous. The whole thing ends up looking and feeling thin, narratively and visually, with Daniels pulling as few approaches to the material as Parks does, so it ends looking repetitive in addition to feeling repetitive. Arguably, the single best thing in the entire film is a goofy, anchronistic bit of banter between Day and Rhodes during the end credits - during the end credits, I say. If that doesn't sum up the slack, profoundly uninspired approach that The United States vs. Billie Holiday takes towards its subject, then I just don't know what.

The hell of it is, it's not even good at that miserable little goal. Turns out that when you strip away most of the gaudiness that makes a Lee Daniels film what it is, you're left with some very slapdash, confused storytelling. We got that a little bit already with The Butler, but at least that had its grandiose scale. The United States vs. Billie Holiday doesn't even have that, by virtue of a plot that completely mangles the passage of time. It almost has the kind of bold-faced overheated melodrama that the director has found success with in the past, given that it feels sometimes like it has more scenes of the titular singer shooting up heroin than not shooting up heroin, but in order to make its political points, the film also can't sensationalise drug use. So instead of a messy epic about the tumultuous life of of an addict, the film simply yawns its way through scene after scene of substance abuse, with only two scenes in the film doing anything to meaningfully try to get at the subjective experience of using smack, and one of those isn't even centered on Billie Holiday herself.

So what do we have, anyway, if it's not melodrama, sensationalism, or grandiosity? Well, first we have Billie (played by pop singer-turned-movie star Andra Day, who took her stage name from Holiday's nickname "Lady Day") visiting an extravagant gnome-like white Southern radio host and hostile gay stereotype Reginald Lord Devine (Leslie Jordan) on his program, which triggers a flashback to her life, I guess? The relationship of the framework narrative to the rest of the movie is inconsistent and quickly forgotten. Anyway, Billie had, by the start of the 1940s, come to controversial national prominence over her recording of the anti-lynching song "Strange Fruit", and this freaked out the government, who were afraid that the song would trigger the civil rights movement. We know this because Suzan-Lori Parks's screenplay at one point has notorious FBI lawyer Roy Cohn (Damian Joseph Quinn) say the line "People are calling the song a starting gun for the so-called civil rights movement", which takes some extraordinary foresight on their part. Seriously, that is one for the bad biopic dialogue hall of fame if I ever I heard one.

The Feds have one idea for how to shut Billie and her dangerous, rabble-rousing song down: take advantage of her well-known drug problems, and just keep arresting her over and over again, planting drugs on her if there's no other way to do it. To this end, they plant a sexy turncoat, Jimmy Fletcher (Trevante Rhodes), in Billie's entourage, and he and his handler, Harry Anslinger (Garrett Hedlund) keep finding ways of harassing and threatening her. And that's, I think, the whole plot? If nothing else, The United States vs. Billie Holiday points out the difference between "eventful" and "dramatic": Billie Holiday live a very busy, chaotic life, but as a narrative, it pretty much just involves the same run-ins with the feds over and over again with almost no significant variation until we finally get to 1959 and the singer's premature death at 44.

This is just not very interesting to watch. Certainly not when it's stretched out to 130 minutes. The film's unmistakable secret weapon is Day, who physically resembles Holiday very little, but who has worked hard to ably re-create the singer's highly distinctive creaky voice, and on top of that has done much to capture her weary misery at being faced with all the bullshit of the world. A Golden Globe win is decidedly over-generous, but there's no denying that whatever human impact the story has is channeled through Day's stretched-thin facial expressions and anger-tinged line readings.She's not demanding our sympathy, allowing her Billie to be easily-annoyed and snappish, but this just makes her that much more appealing human as she oscillates between righteousness, fear, and put-upon pragmatism.

Not that The United States vs. Billie Holiday is giving her all that much to work with. The film's own conception of Billie is scattered, drawn up from various bits and bobs of her biography, including some hastily stuffed-in references to her affair with Tallulah Bankhead (Natasha Lyonne) that have absolutely no impact on anything. Thanks to this indistinct assemble of traits, coupled with the script's reluctance to seriously grapple with the negative impact of heroin usage, she basically doesn't emerge as a person with conflicts to work through, but just a rock around which the rest of the film flows.

Daniels directs this with a flat, trudge-through-the-events professionalism, only coming to life around the edges. The film has some very peculiar scene transitions in the form of quick little flickers of still images that abstractly call up the emotions that are at play, and this is at least unusual in a striking way, though the film never does this consistently. There's a hallucinatory sequence partway through that works terrifically well, blurring past and present in a kind of fuzzy, druggy haze, but the absence of any such trickery in the rest of the film is quite conspicuous. The whole thing ends up looking and feeling thin, narratively and visually, with Daniels pulling as few approaches to the material as Parks does, so it ends looking repetitive in addition to feeling repetitive. Arguably, the single best thing in the entire film is a goofy, anchronistic bit of banter between Day and Rhodes during the end credits - during the end credits, I say. If that doesn't sum up the slack, profoundly uninspired approach that The United States vs. Billie Holiday takes towards its subject, then I just don't know what.

Categories: joyless mediocrity, oscarbait, the dread biopic