So much that is good, that is gone

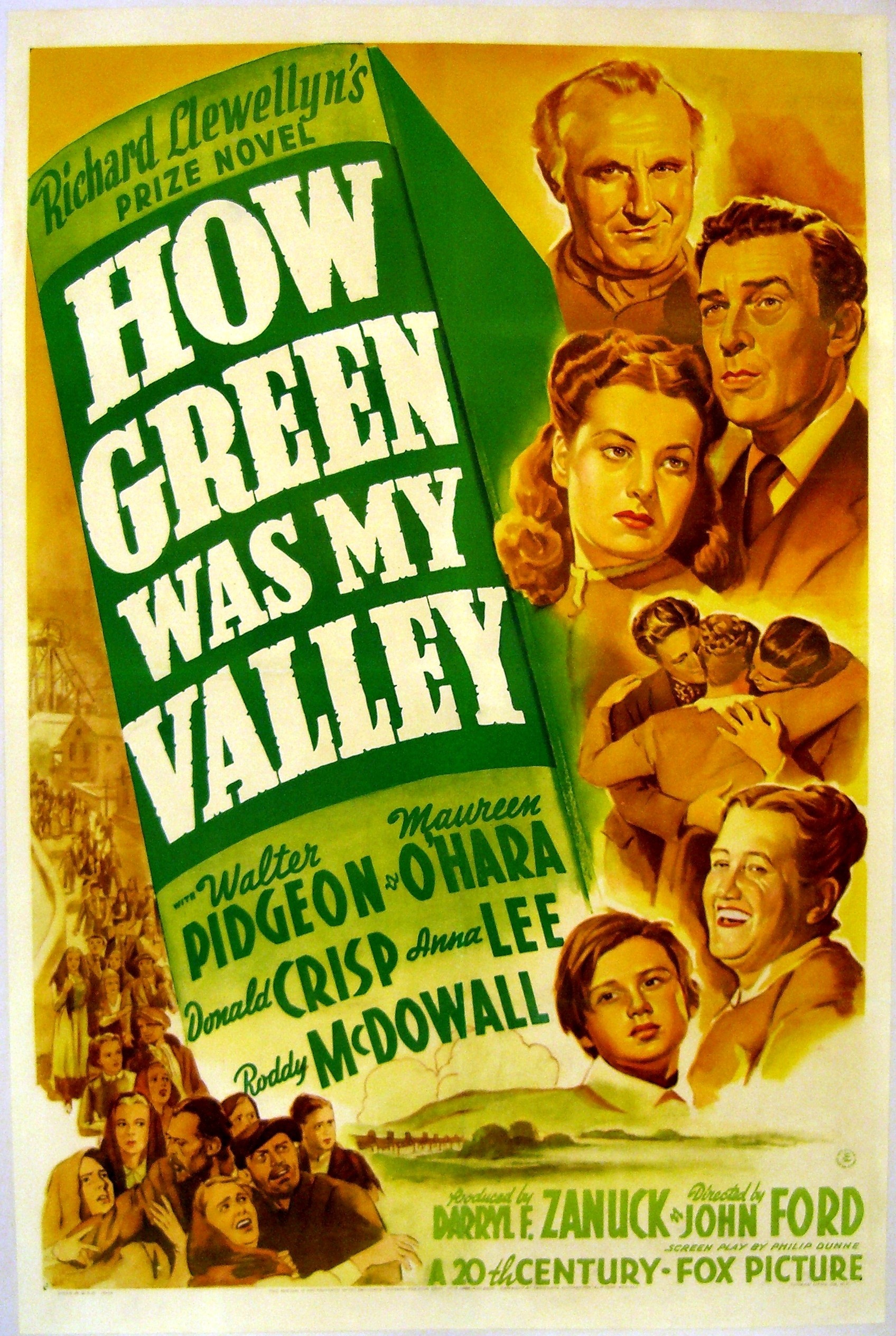

No film has ever deserved its reputation less than How Green Was My Valley, an adaptation by Philip Dunne of Richard Llewellyn's 1939 novel that carefully balances gooey nostalgic sentiment and troubling clarity, is one of the most beautifully-shot films of the 1940s, and represents one of the highest achievements of John Ford's career-long fascination with the ebb and flow of life in a small community and the family as a small-scale extension of that community. For these and other reasons, it won the Academy Award for Best Picture of 1941, and it had awkward good fortune to beat Citizen Kane, which has led to it being routinely described as one of the worst, most unjustified winners of that award in history. Which is an insane fate for a film I'd comfortably anoint as one of the ten best Best Picture winners, but history shakes out the way it will.

Anyway, who cares? The thing that matters is How Green Was My Valley itself, and what a wonderful, lovely thing it is that we have a film like this in the world. The title gives the game away, with that word "was" - this is a reflection on past that can no longer be accessed except through memory, something that we are told in almost exactly those words by the film's narrator (Irving Pichel, best known to me as a director, though he turns out to have quite a robust career as a voiceover artist as well), a man named Huw Morgan, on the backside of middle age. Huw has returned to his hometown in the Welsh coal country for the first time in many years to retrieve some things from the now-abandoned family home; as he does this, he reminisces about he days of his childhood, when he was played by Roddy McDowall, and the valley where he lived was still fresh and green. For the next two hours, Huw will share fragments of memories with us, never quite resolving into a concrete cause-and-effect narrative, though as Huw touches on the moments that seemed to matter most to him in as he was a boy, it becomes clear that the development of Huw's young identity is all tangled up with the evolution and gradual dissolution of the Morgan clan, which is all tangled up with the failure of a labor movement to take hold amongst the coal miners who make up apparently 100% of the town's economy, the slow death of the land, and the chewing maw of industrial capitalism. It's no less a story of the personal miseries of poverty than Ford's The Grapes of Wrath from the previous year, though I like this film even better, in no small part because that message floats alongside the ebbs and flows of a rich and warm family drama without ever stopping the movie cold to shout themes at us.

For that is, let us be clear, the focus of the film: the Morgans and how they slowly fell apart from external and internal forces. This is filtered through so much graceful sentimentality (Pichel's rich, purring voice makes everything in the film automatically sweet and nostalgic, regardless of its intrinsic qualities) and pictorial beauty that it can be hard to notice at first just how much How Green Was My Valley presents, not a world that has been lost, but a world that is in the process of losing itself. The tell comes pretty early on: part of the film's languid opening monologue, delivered without any hurry or urgency, includes the sentiment "In those days, the black slag, the waste of the coal pits, had only begun to cover the sides of our hill." This comes very shortly after a cut directly from the scarred, torn-up, soot-blackened ruin of the town to a brighter, cleaner look at the same landscape. There's no arguing with a good cut (of which there are so many in HGWMV - James B. Clark's editing is a stealth candidate for the most important part of the film, given that the delicate comparison of unrelated shots is mostly how the story's loose causality resolves itself into an actual cohesive cinematic narrative), and this cut tells us exactly what it sounds like: the valley used to be beautiful, and is now ruined. But look back at Huw's exact phrasing: the black slag had only begun - meaning that it had begun, and indeed, as the film drifts by, one thing that keeps dominating our attention in the amazing deep compositions by Ford and cinematographer Arthur C. Miller, rendering the whole movie like an endless chain of 19th Century British landscape paintings, is the looming colliery all the top of the hill, at the end of the road winding sinuously through the town and giving it a living, organic feeling. One of the things that HGWMV is best at is creating elaborate extremely wide compositions in which only a tiny percentage of the frame is dedicated to the subject we're actually looking at - Ford is good enough at constructing images that there's never a mystery about where we're meant to be looking, between the use of lines of composition, of contrasting white or black with the large sweep of grey, and of his beloved internal framing to subdivide the image and privilege certain portions of the screen. But the size of his canvas is such that the frame can be packed with little side details that we are invited but not forced to notice and contemplate, and the colliery, belching thick plumes of black smoke into the clean sky, is in so many shots, never the focus of our attention, but always there, despoiling the landscape, promising the filthy ruin that we first see in a wonderful early shot that drifts past the legs of the adult Huw, falling into his memories, to an open window where stark white walls streaked with black slice across the thick dark greys of the room like a shark.

The point of all this being: How Green Was My Valley is obviously a loving, nostalgic piece, and Huw's warm childhood memories are superlatively brought to live by a gifted cast, spearheaded by Oscar-winner Donald Crisp, whose work as the Morgan paterfamilias Gwylim is the rock around which the rest of the film bends. But the nostalgia is troubled and doubtful. We see things from an adult perspective that Huw wasn't present for and can't understand; this is not a story about a warm, nourishing, lighthearted childhood, but about an adult looking back on his memories and re-evaluating his past in the light of harsher grown-up experience. I would not go so far as to say that adult Huw is an unreliable narrator, but there are tensions laced through his narration between what he tells us and what we see. The most notable of these surround Gwylim; Huw speaks of him as a boundlessly wise and decent man, and this is born out both by the actions of the plot, and by Crisp's steady, stern embodiment of a man who is kind but is more firm. But also, when faced with the most important question in the narrative - whether to strike to protest a cut in wages - Gwylim proves to be wrong. It is not a world in which his mode of decency can win, and this is part of the film's tragedy just as much as Huw's apparent decision to write the pollution and dirt of his childhood out of his conscious memories.

At the same time, the simple pleasures of the film as a portrait of the snug comforts of a well-tended domestic life are too good to be ignored. This, too, has its analogue in the visuals: the interiors in the film, which mostly involve the Morgan home, have been shot with wide lenses and low angles to make the spaces seem a little bit closer and smaller. Most importantly, the film is obsessed with showing us ceilings, one of those little things that simply isn't done, for practical as well as normative reasons. But by insisting on keeping the ceilings of the Morgan home in view almost constantly, Ford and company making that home a cozy little box, just big enough for the people who live in it to move about comfortably. It is a space fitted to the characters.

The film builds the community around that home with similar coziness, though not using the same strategies. This is one of the best examples in all of Ford of one of his favorite repeating tricks, large groups of people performing the same social activity. In particular, the film structures itself around wide shots of the townspeople singing; this happens most prominently during a lovely montage that takes us from liturgical music inside a church to a Welsh song being song by the marching crowd leaving the church, and then to a rowdy drinking song at the Morgans', packed wall to wall with celebrants - all blended together through well-placed dissolves that stress the continuity of these moments just as much as the sharp divisions between songs emphasise the different modes of life being compared. Later on, this same montage signally fails to happen, creating an especially striking symbol for the village's slow disintegration through poverty and hopelessness and the sniping between self-anointed Good People that always attends to Ford's films about tight-knit communities. For as much as he's happy to valorise this way of life, he's equally aware that small communities are especially prone to breaking over interpersonal squabbles and vindictive moralising, and this, too, comes in to color Huw's soft-spoken tribute to his beloved valley.

The push-pull between straightforward nostalgia and a more clear-eyed, sober assessment of what led to the village's decline and the Morgans' dissolution gives How Green Was My Valley a deeply bittersweet feeling: it is a lovely film that depicts a rich world in vivid detail, and also one that tells us at the start that everything fails and there's no stopping it or saving it. And in Ford's hands, this is all told through a wonderful ensemble of sharply-etched figures defined swiftly through writing and performance. It is by no means a radical film, like that other 1941 release that looms so large in its legacy; it's not trying to be. Instead, it is maybe the best version of a particular kind of family melodrama, made by the single filmmaker who has better that this genre than just about anybody else. That is to say, it creates no new forms, but it perfects forms that already existed. And every single time I return to this plain, elegant story of memory and family and loss, I admire it more and find myself more deeply moved - what better sign of an evergreen classic could there be?

For a closer look at one aspect of the film's visual strategies, check out my essay on my favorite shot from the film

Anyway, who cares? The thing that matters is How Green Was My Valley itself, and what a wonderful, lovely thing it is that we have a film like this in the world. The title gives the game away, with that word "was" - this is a reflection on past that can no longer be accessed except through memory, something that we are told in almost exactly those words by the film's narrator (Irving Pichel, best known to me as a director, though he turns out to have quite a robust career as a voiceover artist as well), a man named Huw Morgan, on the backside of middle age. Huw has returned to his hometown in the Welsh coal country for the first time in many years to retrieve some things from the now-abandoned family home; as he does this, he reminisces about he days of his childhood, when he was played by Roddy McDowall, and the valley where he lived was still fresh and green. For the next two hours, Huw will share fragments of memories with us, never quite resolving into a concrete cause-and-effect narrative, though as Huw touches on the moments that seemed to matter most to him in as he was a boy, it becomes clear that the development of Huw's young identity is all tangled up with the evolution and gradual dissolution of the Morgan clan, which is all tangled up with the failure of a labor movement to take hold amongst the coal miners who make up apparently 100% of the town's economy, the slow death of the land, and the chewing maw of industrial capitalism. It's no less a story of the personal miseries of poverty than Ford's The Grapes of Wrath from the previous year, though I like this film even better, in no small part because that message floats alongside the ebbs and flows of a rich and warm family drama without ever stopping the movie cold to shout themes at us.

For that is, let us be clear, the focus of the film: the Morgans and how they slowly fell apart from external and internal forces. This is filtered through so much graceful sentimentality (Pichel's rich, purring voice makes everything in the film automatically sweet and nostalgic, regardless of its intrinsic qualities) and pictorial beauty that it can be hard to notice at first just how much How Green Was My Valley presents, not a world that has been lost, but a world that is in the process of losing itself. The tell comes pretty early on: part of the film's languid opening monologue, delivered without any hurry or urgency, includes the sentiment "In those days, the black slag, the waste of the coal pits, had only begun to cover the sides of our hill." This comes very shortly after a cut directly from the scarred, torn-up, soot-blackened ruin of the town to a brighter, cleaner look at the same landscape. There's no arguing with a good cut (of which there are so many in HGWMV - James B. Clark's editing is a stealth candidate for the most important part of the film, given that the delicate comparison of unrelated shots is mostly how the story's loose causality resolves itself into an actual cohesive cinematic narrative), and this cut tells us exactly what it sounds like: the valley used to be beautiful, and is now ruined. But look back at Huw's exact phrasing: the black slag had only begun - meaning that it had begun, and indeed, as the film drifts by, one thing that keeps dominating our attention in the amazing deep compositions by Ford and cinematographer Arthur C. Miller, rendering the whole movie like an endless chain of 19th Century British landscape paintings, is the looming colliery all the top of the hill, at the end of the road winding sinuously through the town and giving it a living, organic feeling. One of the things that HGWMV is best at is creating elaborate extremely wide compositions in which only a tiny percentage of the frame is dedicated to the subject we're actually looking at - Ford is good enough at constructing images that there's never a mystery about where we're meant to be looking, between the use of lines of composition, of contrasting white or black with the large sweep of grey, and of his beloved internal framing to subdivide the image and privilege certain portions of the screen. But the size of his canvas is such that the frame can be packed with little side details that we are invited but not forced to notice and contemplate, and the colliery, belching thick plumes of black smoke into the clean sky, is in so many shots, never the focus of our attention, but always there, despoiling the landscape, promising the filthy ruin that we first see in a wonderful early shot that drifts past the legs of the adult Huw, falling into his memories, to an open window where stark white walls streaked with black slice across the thick dark greys of the room like a shark.

The point of all this being: How Green Was My Valley is obviously a loving, nostalgic piece, and Huw's warm childhood memories are superlatively brought to live by a gifted cast, spearheaded by Oscar-winner Donald Crisp, whose work as the Morgan paterfamilias Gwylim is the rock around which the rest of the film bends. But the nostalgia is troubled and doubtful. We see things from an adult perspective that Huw wasn't present for and can't understand; this is not a story about a warm, nourishing, lighthearted childhood, but about an adult looking back on his memories and re-evaluating his past in the light of harsher grown-up experience. I would not go so far as to say that adult Huw is an unreliable narrator, but there are tensions laced through his narration between what he tells us and what we see. The most notable of these surround Gwylim; Huw speaks of him as a boundlessly wise and decent man, and this is born out both by the actions of the plot, and by Crisp's steady, stern embodiment of a man who is kind but is more firm. But also, when faced with the most important question in the narrative - whether to strike to protest a cut in wages - Gwylim proves to be wrong. It is not a world in which his mode of decency can win, and this is part of the film's tragedy just as much as Huw's apparent decision to write the pollution and dirt of his childhood out of his conscious memories.

At the same time, the simple pleasures of the film as a portrait of the snug comforts of a well-tended domestic life are too good to be ignored. This, too, has its analogue in the visuals: the interiors in the film, which mostly involve the Morgan home, have been shot with wide lenses and low angles to make the spaces seem a little bit closer and smaller. Most importantly, the film is obsessed with showing us ceilings, one of those little things that simply isn't done, for practical as well as normative reasons. But by insisting on keeping the ceilings of the Morgan home in view almost constantly, Ford and company making that home a cozy little box, just big enough for the people who live in it to move about comfortably. It is a space fitted to the characters.

The film builds the community around that home with similar coziness, though not using the same strategies. This is one of the best examples in all of Ford of one of his favorite repeating tricks, large groups of people performing the same social activity. In particular, the film structures itself around wide shots of the townspeople singing; this happens most prominently during a lovely montage that takes us from liturgical music inside a church to a Welsh song being song by the marching crowd leaving the church, and then to a rowdy drinking song at the Morgans', packed wall to wall with celebrants - all blended together through well-placed dissolves that stress the continuity of these moments just as much as the sharp divisions between songs emphasise the different modes of life being compared. Later on, this same montage signally fails to happen, creating an especially striking symbol for the village's slow disintegration through poverty and hopelessness and the sniping between self-anointed Good People that always attends to Ford's films about tight-knit communities. For as much as he's happy to valorise this way of life, he's equally aware that small communities are especially prone to breaking over interpersonal squabbles and vindictive moralising, and this, too, comes in to color Huw's soft-spoken tribute to his beloved valley.

The push-pull between straightforward nostalgia and a more clear-eyed, sober assessment of what led to the village's decline and the Morgans' dissolution gives How Green Was My Valley a deeply bittersweet feeling: it is a lovely film that depicts a rich world in vivid detail, and also one that tells us at the start that everything fails and there's no stopping it or saving it. And in Ford's hands, this is all told through a wonderful ensemble of sharply-etched figures defined swiftly through writing and performance. It is by no means a radical film, like that other 1941 release that looms so large in its legacy; it's not trying to be. Instead, it is maybe the best version of a particular kind of family melodrama, made by the single filmmaker who has better that this genre than just about anybody else. That is to say, it creates no new forms, but it perfects forms that already existed. And every single time I return to this plain, elegant story of memory and family and loss, I admire it more and find myself more deeply moved - what better sign of an evergreen classic could there be?

For a closer look at one aspect of the film's visual strategies, check out my essay on my favorite shot from the film