How could I have known that murder could sometimes smell like honeysuckle?

A review requested by Benjamin, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

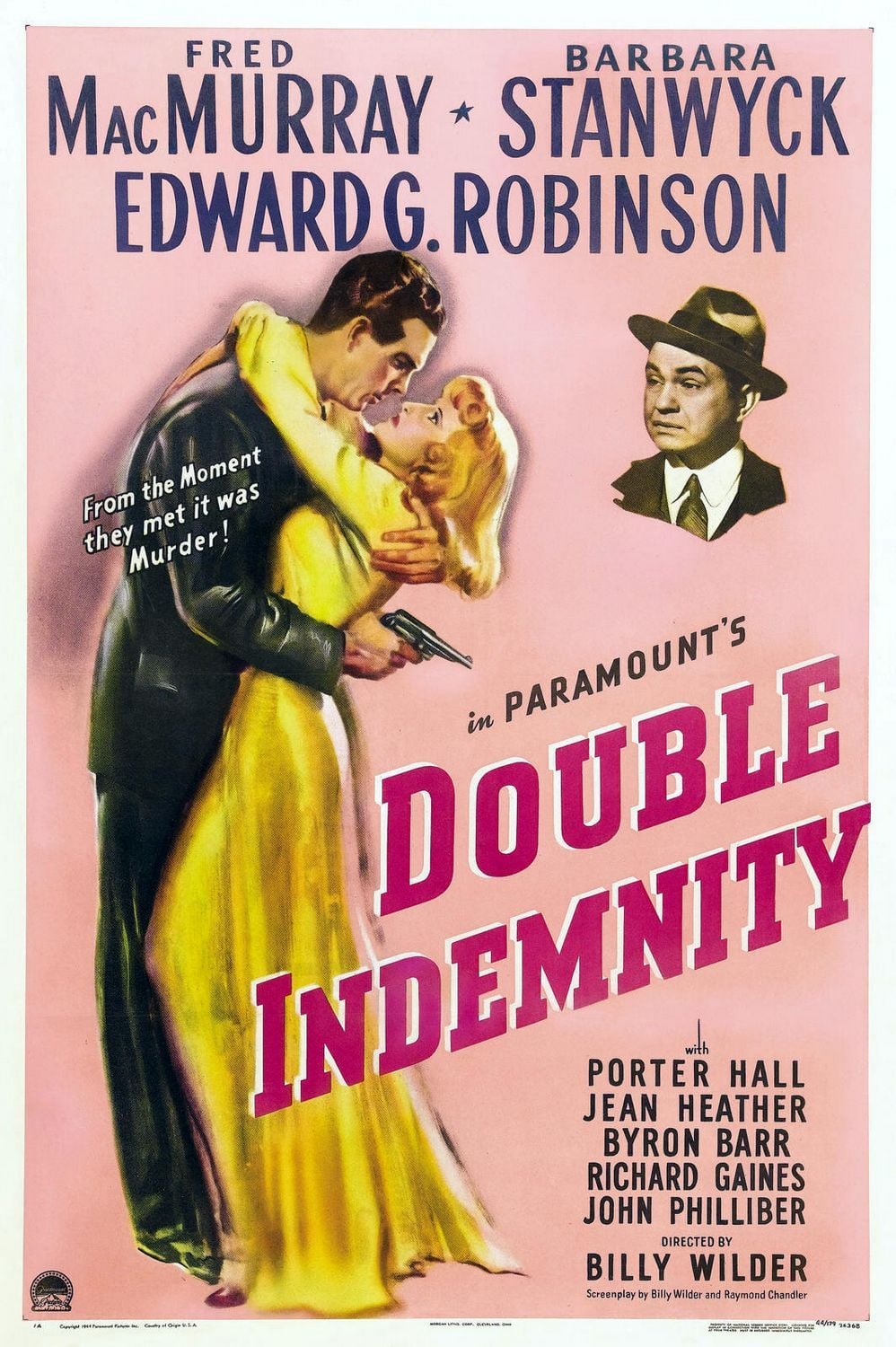

Double Indemnity is the noir of noirs. To be sure, there are more typical examples of the strengths of the film noir style, and probably films that better encapsulations of the characteristic worldview of noir, but maybe there is none more perfect as a movie. It is this film, more than any other I can name, that sums up the appeal of noir (for those of us who find it appealing), and can create a lifelong passion for the style (for those of us who consider it to be a lifelong passion; which is most of the classic-era cinephiles I have met in my life). It has all the goods, neatly assembled in one place: sordid characters blithely flaunting any decent person's sense of morality, good people made out to be saps and chumps, dialogue so hard boiled that you could use it to drive railroad spikes.

And doom! Such a thick, meaty sense of omnipresent doom! It is a customary trope of film noir to suggest that the protagonist's fate was sealed before the plot every even began, but few films do it as directly and nastily as Double Indemnity (especially not as early as 1944, when film noir hadn't yet been described and was still more of a one-off exercise than a major tendency). The film is a fairly early example of an overarching flashback structure - the ol' "start at the end, then explain how we got here" gambit, except it wasn't old yet at all, which means that audiences of that period would have had little experience with a movie that opens the way this one does: in April 1938, so late at night that it's early in the morning, insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) stumbles and staggers into the offices of his employer, Pacific All-Risk Insurance. He makes his way to the empty office of claims manager Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson, when we finally meet him in the flesh), where he starts delivering what he pointedly refuses to characterise as a "confession" into Keyes's dictaphone. "I killed him for money, and a woman", he says, with MacMurray providing an appropriately sardonic twist on the lines, "and I didn't get the money and I didn't get the woman". That's a whole lot of information, and it leaves basically no surprises to be uncovered over the rest of the film's 107 minutes. It just leaves the solemn, sad farce of watching Walter enthusiastically dig himself a deep, dank hole, and then just as enthusiastically diving head-first into it.

The contents of that farce, if by some horrible misfortune you've never seen Double Indemnity, nor know aught of its plot, is an insurance fraud scheme. One a normal day in the summer of 1937, Walter travels to the home of one of his clients on a perfectly normal trip to discuss renewing the man's automobile insurance. But Mr. Dietrichson (Tom Powers) isn't there. Instead, Walter meets Dietrichson's second wife, Phyllis (Barbara Stanwyck) freshly scrubbed and shiny from a bath, and wearing nothing but a towel. Fast-forward a little while, and Walter and Phyllis are sleeping together, and concocting a plot to kill Dietrichson by staging a train accident - thus not only netting $50,000 for the secret life insurance policy Walter has arranged without Dietrichson learning about it, but also triggering a "double indemnity" clause for a second $50,000 in the event of something ludicrously unlikely, such as a train accident. The murder itself goes off without a hitch, and even the great Keyes, one of the finest insurance investigators to ever draw breath, hardly suspects anything - at first. At second, though, Keyes starts to tease out that something doesn't add up, and...

...And what? We know from the start how this is going to play out, but even so, Double Indemnity doesn't go in quite the direction one might think. Keyes doesn't get close to Walter - he never even suspects Walter, outside of an immediately-dismissed bit of due diligence - and Walter never panics and works from inside the system to hide his tracks. Instead, the second half of the film (the murder occurs shortly before the midway point) finds Walter just being very nervous, but in a passive, miserable way, as though killing Dietrichson was the entirety of what he could do as far as physical action, and now it's just a matter of sitting around waiting and snapping at Phyllis for not being sufficiently perturbed. And not, really, because Phyllis has been sneakily working things around all along to set Walter up as a patsy. It's more that these are just two fundamentally hapless people; able to concoct a murder scheme, because they're nasty, scheming bastards, but too quickly given to sniping paranoia to actually come up with any decent conspiracies after that. There comes a point where they're mostly just waiting around to get caught, and they know it.

This is the quintessence of noir morality. As it should be - Double Indemnity has peerless hard-boiled credentials, coming from a novel by James M. Cain, the great literary investigator of festering moral turpitude in the southern California sun, and with a screenplay co-authored by iconic detective story author Raymond Chandler. Chandler worked on the screenplay along with director Billy Wilder, making just his third Hollywood feature, and the one where he fully cemented the voice that would dominate nearly all of his best films thereafter: a caustic, wildly misanthropic sense of cynicism spiked by jet black comedy. Double Indemnity is one of Wilder's most unapologetically nasty films, and even pretty nasty by the standards of film noir, world cinema's most nihilistic genre. It's a film in which the two protagonists pretty much just scamper into doing evil: no moments where Walter needs to be seduced into breaking his moral code, he pretty much decides instantly that Phyllis is worth killing for, really without her even needing to ask for it. And it's a film in which Keyes, presented throughout as a tough-as-nails genius investigator, and certainly as the only all-good person we meet for any length of time, is a sentimental sap whose brilliance is no match for his naïve belief in the basic goodness of people (the film does not by any means foreground this, and perhaps doesn't even intend it; but the moment where we learn that Keyes doesn't suspect Walter, his logic is basically "because I don't want him to be the killer". There's probably a queer reading of this, but I'm not the critic to make it).

Tempering this slightly is the marvelous presentation of Walter and Phyllis as being, honestly, pretty inept bad guys. What we see in them, in various subtle ways, is less the will to do evil than a sweaty, panicked, effortful desire to be evil. Phyllis is a hell of a femme fatale, and Stanwyck's performance is one for the ages: the way she goes empty and slack whenever she's not portraying the sultry vixen for Walter is one of the most interesting grace notes in any performance in all of noir, as fine a depiction of sociopathy as the movies have made. But she's not an glamorous murder goddess like so many noir villainesses. Wickedness is a pose, one that she has to maintain through great effort, and she grows increasingly desperate and petulant across the movie as that effort gets harder. 1944 is awfully early to credit anybody for playing a meta-narrative game with hard-boiled fiction tropes, but I'm almost tempted to say that Stanwyck plays Phyllis as a woman who realises that she's in a narrative universe where bad girls have to act a certain way, and attempts to oblige; but she's really just a nasty-minded brat with a husband to get rid of, not a sultry monster. It's a better fit for Stanwyck's natural playing style - she was the great pragmatist of her era of Hollywood, an actor given to under-stressing and ironic self-aware amusement and projecting a smart wariness that feels shockingly, uncomfortably modern for classic Hollywood (her towering pair of triumphs from 1941, The Lady Eve and Ball of Fire, are to me the two best examples of this mode). Phyllis as a grubby little killer play-acting as a Cain/Chandler ice queen fits into this just perfectly.

MacMurray and Robinson are no slouches themselves - the latter, playing a wisecracking hard-boiled detective who turns into a tragic hero in the film's last scene, is especially wonderful, and Robinson's failure to receive an Academy Award nomination for this role is to my mind one of the most appalling oversights in Oscar history. Not many performers could share a film with Stanwyck's Phyllis and not seem like they were at least somewhat boring, but MacMurray's hungry, staring, horny killer is awfully good: unlike many noir leads, MacMurray isn't looking to make his character a misbegotten soul. He, like Phyllis, is just a grimy little rotter, and unlike her, he isn't even interesting about it (this is not a slam against the film or the character).

The characters' vicious little meanness is distinctive even after more than seventy years of noir and neo-noir efforts to make ever-more vile, bleak worlds for ever-more blackhearted souls. There are plenty of obvious reasons for this, even besides the great performances: for one, the stark contrast between a shiny, sunny pre-WWII vision of Los Angeles with the barbarity enacted there (a Cain specialty), as well as the visual dynamic between bright daylight exteriors and close, unpleasant shadows in John F. Seitz's cinematography. And let us not overlook the airtight dialogue Wilder and Chandler provide, snappy and bitter, florid and overworked but also sullenly hilarious. It's not by any means one of Wilder's funniest films, but it's certainly not without its sense of humor, both in the writing and in the ironic, acerbic visuals, from the disorienting first appearance of Stanwyck in a towel through to the scenes in a local grocery store, with the two killers feebly making their plans next to dog food and cake mix.

Mostly, though, the film is interested in savage tension, with a strong reliance on close-ups to make everything seem unpleasantly intimate - the most exaggerated moment being when the camera placidly glides onto Phyllis's implacable face while her husband is being noisily choked to death just off-screen. Or perhaps the look at her alarm when she stands barely out of side behind an open door as Keyes happily discusses her guilt. But there are also a great many other, less showy moments where Wilder, Seitz, and editor Doane Harrison rely on MacMurray and Stanwyck's big, beautiful, slightly sweaty faces to convey an oppressive mood. There are many phone conversations in this film, mostly shot with the same small number of angles, as though we're trying to muscle our way into the conversation; it is a film eager and willing to make us as intimate with these killers as they can. This, above all, is the key to Double Indemnity's longevity as one of the real nasty pieces of work in its genre: the twists and turns are relatively standard, but the desperation of the characters, evoked in the terrific performances, isn't standard at all, and it's as a character study that this stands apart as one of the absolute, quintessential masterpieces of film noir and midcentury American cinema.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Double Indemnity is the noir of noirs. To be sure, there are more typical examples of the strengths of the film noir style, and probably films that better encapsulations of the characteristic worldview of noir, but maybe there is none more perfect as a movie. It is this film, more than any other I can name, that sums up the appeal of noir (for those of us who find it appealing), and can create a lifelong passion for the style (for those of us who consider it to be a lifelong passion; which is most of the classic-era cinephiles I have met in my life). It has all the goods, neatly assembled in one place: sordid characters blithely flaunting any decent person's sense of morality, good people made out to be saps and chumps, dialogue so hard boiled that you could use it to drive railroad spikes.

And doom! Such a thick, meaty sense of omnipresent doom! It is a customary trope of film noir to suggest that the protagonist's fate was sealed before the plot every even began, but few films do it as directly and nastily as Double Indemnity (especially not as early as 1944, when film noir hadn't yet been described and was still more of a one-off exercise than a major tendency). The film is a fairly early example of an overarching flashback structure - the ol' "start at the end, then explain how we got here" gambit, except it wasn't old yet at all, which means that audiences of that period would have had little experience with a movie that opens the way this one does: in April 1938, so late at night that it's early in the morning, insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) stumbles and staggers into the offices of his employer, Pacific All-Risk Insurance. He makes his way to the empty office of claims manager Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson, when we finally meet him in the flesh), where he starts delivering what he pointedly refuses to characterise as a "confession" into Keyes's dictaphone. "I killed him for money, and a woman", he says, with MacMurray providing an appropriately sardonic twist on the lines, "and I didn't get the money and I didn't get the woman". That's a whole lot of information, and it leaves basically no surprises to be uncovered over the rest of the film's 107 minutes. It just leaves the solemn, sad farce of watching Walter enthusiastically dig himself a deep, dank hole, and then just as enthusiastically diving head-first into it.

The contents of that farce, if by some horrible misfortune you've never seen Double Indemnity, nor know aught of its plot, is an insurance fraud scheme. One a normal day in the summer of 1937, Walter travels to the home of one of his clients on a perfectly normal trip to discuss renewing the man's automobile insurance. But Mr. Dietrichson (Tom Powers) isn't there. Instead, Walter meets Dietrichson's second wife, Phyllis (Barbara Stanwyck) freshly scrubbed and shiny from a bath, and wearing nothing but a towel. Fast-forward a little while, and Walter and Phyllis are sleeping together, and concocting a plot to kill Dietrichson by staging a train accident - thus not only netting $50,000 for the secret life insurance policy Walter has arranged without Dietrichson learning about it, but also triggering a "double indemnity" clause for a second $50,000 in the event of something ludicrously unlikely, such as a train accident. The murder itself goes off without a hitch, and even the great Keyes, one of the finest insurance investigators to ever draw breath, hardly suspects anything - at first. At second, though, Keyes starts to tease out that something doesn't add up, and...

...And what? We know from the start how this is going to play out, but even so, Double Indemnity doesn't go in quite the direction one might think. Keyes doesn't get close to Walter - he never even suspects Walter, outside of an immediately-dismissed bit of due diligence - and Walter never panics and works from inside the system to hide his tracks. Instead, the second half of the film (the murder occurs shortly before the midway point) finds Walter just being very nervous, but in a passive, miserable way, as though killing Dietrichson was the entirety of what he could do as far as physical action, and now it's just a matter of sitting around waiting and snapping at Phyllis for not being sufficiently perturbed. And not, really, because Phyllis has been sneakily working things around all along to set Walter up as a patsy. It's more that these are just two fundamentally hapless people; able to concoct a murder scheme, because they're nasty, scheming bastards, but too quickly given to sniping paranoia to actually come up with any decent conspiracies after that. There comes a point where they're mostly just waiting around to get caught, and they know it.

This is the quintessence of noir morality. As it should be - Double Indemnity has peerless hard-boiled credentials, coming from a novel by James M. Cain, the great literary investigator of festering moral turpitude in the southern California sun, and with a screenplay co-authored by iconic detective story author Raymond Chandler. Chandler worked on the screenplay along with director Billy Wilder, making just his third Hollywood feature, and the one where he fully cemented the voice that would dominate nearly all of his best films thereafter: a caustic, wildly misanthropic sense of cynicism spiked by jet black comedy. Double Indemnity is one of Wilder's most unapologetically nasty films, and even pretty nasty by the standards of film noir, world cinema's most nihilistic genre. It's a film in which the two protagonists pretty much just scamper into doing evil: no moments where Walter needs to be seduced into breaking his moral code, he pretty much decides instantly that Phyllis is worth killing for, really without her even needing to ask for it. And it's a film in which Keyes, presented throughout as a tough-as-nails genius investigator, and certainly as the only all-good person we meet for any length of time, is a sentimental sap whose brilliance is no match for his naïve belief in the basic goodness of people (the film does not by any means foreground this, and perhaps doesn't even intend it; but the moment where we learn that Keyes doesn't suspect Walter, his logic is basically "because I don't want him to be the killer". There's probably a queer reading of this, but I'm not the critic to make it).

Tempering this slightly is the marvelous presentation of Walter and Phyllis as being, honestly, pretty inept bad guys. What we see in them, in various subtle ways, is less the will to do evil than a sweaty, panicked, effortful desire to be evil. Phyllis is a hell of a femme fatale, and Stanwyck's performance is one for the ages: the way she goes empty and slack whenever she's not portraying the sultry vixen for Walter is one of the most interesting grace notes in any performance in all of noir, as fine a depiction of sociopathy as the movies have made. But she's not an glamorous murder goddess like so many noir villainesses. Wickedness is a pose, one that she has to maintain through great effort, and she grows increasingly desperate and petulant across the movie as that effort gets harder. 1944 is awfully early to credit anybody for playing a meta-narrative game with hard-boiled fiction tropes, but I'm almost tempted to say that Stanwyck plays Phyllis as a woman who realises that she's in a narrative universe where bad girls have to act a certain way, and attempts to oblige; but she's really just a nasty-minded brat with a husband to get rid of, not a sultry monster. It's a better fit for Stanwyck's natural playing style - she was the great pragmatist of her era of Hollywood, an actor given to under-stressing and ironic self-aware amusement and projecting a smart wariness that feels shockingly, uncomfortably modern for classic Hollywood (her towering pair of triumphs from 1941, The Lady Eve and Ball of Fire, are to me the two best examples of this mode). Phyllis as a grubby little killer play-acting as a Cain/Chandler ice queen fits into this just perfectly.

MacMurray and Robinson are no slouches themselves - the latter, playing a wisecracking hard-boiled detective who turns into a tragic hero in the film's last scene, is especially wonderful, and Robinson's failure to receive an Academy Award nomination for this role is to my mind one of the most appalling oversights in Oscar history. Not many performers could share a film with Stanwyck's Phyllis and not seem like they were at least somewhat boring, but MacMurray's hungry, staring, horny killer is awfully good: unlike many noir leads, MacMurray isn't looking to make his character a misbegotten soul. He, like Phyllis, is just a grimy little rotter, and unlike her, he isn't even interesting about it (this is not a slam against the film or the character).

The characters' vicious little meanness is distinctive even after more than seventy years of noir and neo-noir efforts to make ever-more vile, bleak worlds for ever-more blackhearted souls. There are plenty of obvious reasons for this, even besides the great performances: for one, the stark contrast between a shiny, sunny pre-WWII vision of Los Angeles with the barbarity enacted there (a Cain specialty), as well as the visual dynamic between bright daylight exteriors and close, unpleasant shadows in John F. Seitz's cinematography. And let us not overlook the airtight dialogue Wilder and Chandler provide, snappy and bitter, florid and overworked but also sullenly hilarious. It's not by any means one of Wilder's funniest films, but it's certainly not without its sense of humor, both in the writing and in the ironic, acerbic visuals, from the disorienting first appearance of Stanwyck in a towel through to the scenes in a local grocery store, with the two killers feebly making their plans next to dog food and cake mix.

Mostly, though, the film is interested in savage tension, with a strong reliance on close-ups to make everything seem unpleasantly intimate - the most exaggerated moment being when the camera placidly glides onto Phyllis's implacable face while her husband is being noisily choked to death just off-screen. Or perhaps the look at her alarm when she stands barely out of side behind an open door as Keyes happily discusses her guilt. But there are also a great many other, less showy moments where Wilder, Seitz, and editor Doane Harrison rely on MacMurray and Stanwyck's big, beautiful, slightly sweaty faces to convey an oppressive mood. There are many phone conversations in this film, mostly shot with the same small number of angles, as though we're trying to muscle our way into the conversation; it is a film eager and willing to make us as intimate with these killers as they can. This, above all, is the key to Double Indemnity's longevity as one of the real nasty pieces of work in its genre: the twists and turns are relatively standard, but the desperation of the characters, evoked in the terrific performances, isn't standard at all, and it's as a character study that this stands apart as one of the absolute, quintessential masterpieces of film noir and midcentury American cinema.

Categories: billy wilder, crime pictures, film noir, the cinema of wwii