Making bank

"Based on a true story" is such a marvelous bit of hand-waving. In the case of The Bank Job it means, "we are going to try and gloss over some of the more unbelievable elements of our story by making you think it's all factual." They needn't have bothered; true or fake, The Bank Job is a brisk entertainment that doesn't need believability to work.

The true story, at any rate, is pretty thin gruel: in 1971, a ham radio operator overheard a bank robbery in progress, and reported it to the police. After a few days, a D-notice - a government edict gagging the media - was put on the story, and it slipped into the mists of time. From that tottering skeleton, screenwriters Dick Clement & Ian La Frenais (formerly of Tracey Ullman's coterie, among many other shared credits) and director Roger Donaldson (a New Zealander whose career has included much solid work, but all I want to do is harp on his 1997 disaster Dante's Peak) have fashioned a fairly preposterous but breezy and delightful conspiracy tale of a safe deposit box with pornographic photos of a Royal Personage, a black militant whose politics are a smokescreen for his drug and prostitution rings, and a cadre of schlubby blokes who misadventure their way into one of the biggest bank heists in history.

Giving away any more than that would spoil things, and isn't the best part about a heist movie watching how plans are made and then unravel? The Bank Job admittedly isn't one of history's great heist movies, but it gets the job done well enough. And it's a credit to everyone involved that once the actual robbery is completed and the film moves on to the aftermath of the crime (one of two models for the caper film - the other is to end at the successful completion of the caper), a point at which most films start to run out of gas and thrash around a bit, The Bank Job in fact starts to pick up. While the opening is fun and playful, the second half is in many places quite the intense thriller: the danger in the caper is all back-loaded, and the filmmakers pull no punches in convincing us of just how dangerous it is.

There's an unexpected seriousness that makes the film more memorable than most of the seemingly endless run of British crime pictures to come out in the wake of Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. Death, in this film - and there is death, some of it quite unexpected - has a bite that's usually missing from films of this type, due in no small part to how very vicious death can be here. It's part of the film's program of smuggling a bitter pill in underneath the stylish generic facade, not only making subtle but unmistakable jabs at the "whee, violence!" mentality typical of crime pictures, but also foregrounding with equal subtlety the economic world of Britain in the 1970s, the world of joblessness and recession that would eventually end in punk and Thatcher.

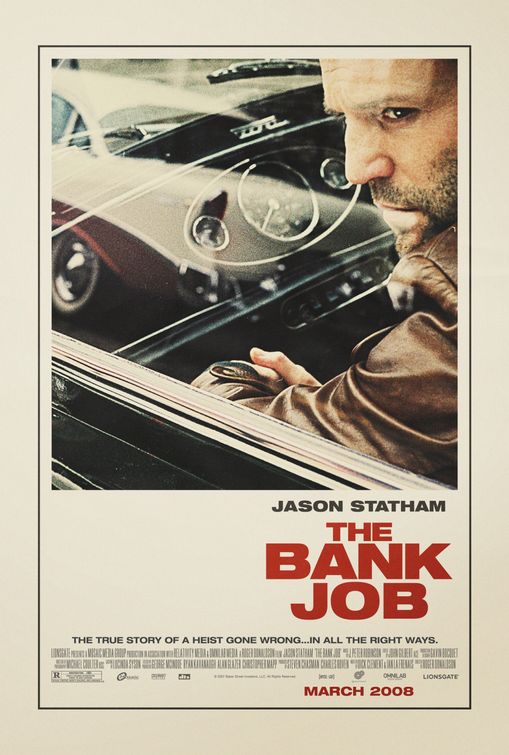

This isn't really the kind of film that requires a crackerjack cast, which is good, because star Jason Statham isn't all that much of an actor. I love him, for reasons that continuously evade me, but he's never been called on to do much except glower and be British. To be sure, The Bank Job is not a film like any other in his career - it's much grittier and less action-packed than almost anything he's done - and for the first time it's possible to see some glistening humanity in the back of his eyes that does more than Acting could. The rest of the cast is just there to fill in the blanks and have fun, really: Saffron Burrows is reliably easy on the eyes, where the (to Americans) mostly unknown Steven Campbell Moore and Daniel Mays et al get to play at being various modes of tough guys.

Rather, this is the kind of film that requires a crackerjack team behind the camera, and thankfully it has just that: editor John Gilbert in particular ought to have some sort of medal for the work he's turned in on this project, cutting between points-of-view and sometimes even time periods with an easy elegance that keeps the whole thing lively (and there's really nothing more important for a caper film than to seem lively). Michael Coulter, the cinematographer of pretty much any British romantic comedy you could name from the last 15 years, brings in a nicely '70s-esque brown flatness to the film. It's no Zodiac, but it looks like the era ought to.

But it seems wrong not to cut to the chase and put the credit where it belongs: Roger Donaldson, who has made good films and bad films, but who is through and through and entirely solid craftsman. The Bank Job doesn't break any new ground, but in its comforting familiarity, it's extremely well-built. The ending may be a bit too happily-ever-after, the concept a bit too flighty, but it's all in the name of good fun, and for all its toughness, the film is nothing if not a top-notch entertainment.

The true story, at any rate, is pretty thin gruel: in 1971, a ham radio operator overheard a bank robbery in progress, and reported it to the police. After a few days, a D-notice - a government edict gagging the media - was put on the story, and it slipped into the mists of time. From that tottering skeleton, screenwriters Dick Clement & Ian La Frenais (formerly of Tracey Ullman's coterie, among many other shared credits) and director Roger Donaldson (a New Zealander whose career has included much solid work, but all I want to do is harp on his 1997 disaster Dante's Peak) have fashioned a fairly preposterous but breezy and delightful conspiracy tale of a safe deposit box with pornographic photos of a Royal Personage, a black militant whose politics are a smokescreen for his drug and prostitution rings, and a cadre of schlubby blokes who misadventure their way into one of the biggest bank heists in history.

Giving away any more than that would spoil things, and isn't the best part about a heist movie watching how plans are made and then unravel? The Bank Job admittedly isn't one of history's great heist movies, but it gets the job done well enough. And it's a credit to everyone involved that once the actual robbery is completed and the film moves on to the aftermath of the crime (one of two models for the caper film - the other is to end at the successful completion of the caper), a point at which most films start to run out of gas and thrash around a bit, The Bank Job in fact starts to pick up. While the opening is fun and playful, the second half is in many places quite the intense thriller: the danger in the caper is all back-loaded, and the filmmakers pull no punches in convincing us of just how dangerous it is.

There's an unexpected seriousness that makes the film more memorable than most of the seemingly endless run of British crime pictures to come out in the wake of Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. Death, in this film - and there is death, some of it quite unexpected - has a bite that's usually missing from films of this type, due in no small part to how very vicious death can be here. It's part of the film's program of smuggling a bitter pill in underneath the stylish generic facade, not only making subtle but unmistakable jabs at the "whee, violence!" mentality typical of crime pictures, but also foregrounding with equal subtlety the economic world of Britain in the 1970s, the world of joblessness and recession that would eventually end in punk and Thatcher.

This isn't really the kind of film that requires a crackerjack cast, which is good, because star Jason Statham isn't all that much of an actor. I love him, for reasons that continuously evade me, but he's never been called on to do much except glower and be British. To be sure, The Bank Job is not a film like any other in his career - it's much grittier and less action-packed than almost anything he's done - and for the first time it's possible to see some glistening humanity in the back of his eyes that does more than Acting could. The rest of the cast is just there to fill in the blanks and have fun, really: Saffron Burrows is reliably easy on the eyes, where the (to Americans) mostly unknown Steven Campbell Moore and Daniel Mays et al get to play at being various modes of tough guys.

Rather, this is the kind of film that requires a crackerjack team behind the camera, and thankfully it has just that: editor John Gilbert in particular ought to have some sort of medal for the work he's turned in on this project, cutting between points-of-view and sometimes even time periods with an easy elegance that keeps the whole thing lively (and there's really nothing more important for a caper film than to seem lively). Michael Coulter, the cinematographer of pretty much any British romantic comedy you could name from the last 15 years, brings in a nicely '70s-esque brown flatness to the film. It's no Zodiac, but it looks like the era ought to.

But it seems wrong not to cut to the chase and put the credit where it belongs: Roger Donaldson, who has made good films and bad films, but who is through and through and entirely solid craftsman. The Bank Job doesn't break any new ground, but in its comforting familiarity, it's extremely well-built. The ending may be a bit too happily-ever-after, the concept a bit too flighty, but it's all in the name of good fun, and for all its toughness, the film is nothing if not a top-notch entertainment.

Categories: british cinema, caper films, crime pictures, the statham, thrillers