In fair Bechuanaland, where we make our scene

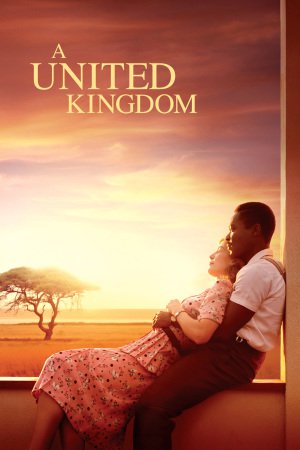

First things first: David Oyelowo and Rosamund Pike are just luminous together onscreen. As the central couple of A United Kingdom, they're bound by the conventions of both the genre (prim, awards-courting, real-life message movies) and by the time the story is set (England and the British Empire in the 1940s and 1950s), and so their love affair is mostly a tidy emotional one; there's no lust or real sexuality here. But even obliged to work strictly within a grandmotherly conception of romance, the two actors generate enough heat to light up the entirety of what would otherwise be a pretty dim and drab motion picture.

The film is the third feature directed by Amma Asante, and its strengths and weaknesses largely mimic her last film, the 2013 historical biopic Belle: the strengths, beyond the enormously good central performances (and I can't help feeling that "enormously good" still sells Oyelowo and Pike short), are largely focused on Asante's keen sense of picking a good subject, relating to the history of English racism, and bringing to the fore a story that deserves more attention than it has historically received (given the international significance of the story that A United Kingdom tells, it seems doubly ludicrous that it's so relatively obscure). The weakness, simply put, is that it's a British prestige picture with Something to Say, which lacquers everything beneath a veneer of middlebrow artistic sensitivity from which no real feeling or style can emerge (I believe I mentioned that it's lustless and sexless? This is why). Having gone two-for-two now in making films that stride eagerly into this same trap, I'm not quite sure what to make of Asante's burgeoning career: her skill with actors is obvious, and it's frustrating to see that skill playing itself out against such lazy backdrops.

The film, anyway, is about the whirlwind courtship (compressed in Guy Hibbert's screenplay) between Seretse Khama (Oyelowo), of the Bechuanaland Protectorate, studying law in London, and Ruth Williams (Pike), a clerk at Lloyd's of London, culminating in their decision to get married. This causes a problem for two reasons, the more immediately pressing of which is that Seretse is black and Ruth is white, and this is 1947. The second, and ultimately the more consequential, is that Seretse is hereditary king of the Bamangwato people of Bechuanaland, studying while his uncle Naledi (Terry Pheto) serves as regent. That's already enough for the young couple's relationship to start an international incident; where things get really nasty is that Bechuanaland borders South Africa, and that territory's newly ascendant National Party of white Afrikaners, with its brand-new system of apartheid, takes none too happy a view of its next-door neighbor having a mixed-race couple ruling. And so the marriage is immediately threatened both by Bamangwato traditionalists, furious that Seretse married an outsider, and the British government trying to break the couple apart at the behest of South Africa.

No surprise that this all ends happily (it's hard to imagine that there'd be a movie at all if it didn't), though just how happily is rather extreme: Seretse Khama would take the nascent anti-British sentiment that this event stirred up, and in the 1960s would help Bechuanaland negotiate its freedom from England, helping to establish the protectorate as the independent nation of Botswana in 1965, and serving as its first elected president. Getting to that point (which the movie sums up in a closing title card) from 1947 takes an awful lot of plot, more frankly than the 111-minute feature is prepared for. And Hibbert makes some awfully odd choices about what to emphasise as a result, leading to a film that focuses on things that are rarely the most interesting or cinematic.

Bluntly, the bulk of A United Kingdom turns out to be a drama about political negotiations, which is probably the best way to tell this story if what you care about is getting things laid out clearly, to maximise the audience's "aha, I did not know that; now I do" response. This leaves, for example, very damn little time for such trivialities as the actual relationship between Seretse and Ruth (they spend the bulk of the film on separate continents, as Seretse finds himself exiled in England while Ruth endears herself to the population that so mistrusts her). Given that Oyelowo and Pike are so clearly the film's strength, any time spent away from them feels like time wasted, and particularly, it feels like a crime against art that we get so little of their dazzled courtship, the most emotionally true and engaging part of the film. The little details of giddy expressions and stolen glances as the two discuss jazz and revel in the intoxication of young romance give both actors some wonderful chances to do subtle character work (Oyelowo is never better than in the first thirty minutes; the role transforms into a stock "yell about injustice" character, and he does it well enough, but it's just inherently less interesting). The rest of the movie lacks that, though Pike manages to make the most of the character that the film spends less time with, but gives more dynamic material to.

Meanwhile, the plot and characters and actors are trapped in the gilded cage of a very nice movie: the chief thing I could say about Sam McCurdy's cinematography is that he and Asante are awfully jejune about using digital color correction to make the red sands of the Kalahari look rather suspiciously orange, under the altogether offensively teal skies. And that he makes the halls of British government look dusky, with diffuse white light, in the manner of literally every other movie of the 21st Century set in the halls of British government. It's all perfectly functional and immodestly boring, the kind of biopic that presents history as a carefully preserved museum display, rather than lending it any sort of vitality. Seretse and Ruth deserve more than that; Oyelowo and Pike deserve more than that too, and in their vigorously felt, physically expressive performances, they almost manage to force A United Kingdom to be more than that, but in the face of this much staid respectability, an actor can only do so much.

The film is the third feature directed by Amma Asante, and its strengths and weaknesses largely mimic her last film, the 2013 historical biopic Belle: the strengths, beyond the enormously good central performances (and I can't help feeling that "enormously good" still sells Oyelowo and Pike short), are largely focused on Asante's keen sense of picking a good subject, relating to the history of English racism, and bringing to the fore a story that deserves more attention than it has historically received (given the international significance of the story that A United Kingdom tells, it seems doubly ludicrous that it's so relatively obscure). The weakness, simply put, is that it's a British prestige picture with Something to Say, which lacquers everything beneath a veneer of middlebrow artistic sensitivity from which no real feeling or style can emerge (I believe I mentioned that it's lustless and sexless? This is why). Having gone two-for-two now in making films that stride eagerly into this same trap, I'm not quite sure what to make of Asante's burgeoning career: her skill with actors is obvious, and it's frustrating to see that skill playing itself out against such lazy backdrops.

The film, anyway, is about the whirlwind courtship (compressed in Guy Hibbert's screenplay) between Seretse Khama (Oyelowo), of the Bechuanaland Protectorate, studying law in London, and Ruth Williams (Pike), a clerk at Lloyd's of London, culminating in their decision to get married. This causes a problem for two reasons, the more immediately pressing of which is that Seretse is black and Ruth is white, and this is 1947. The second, and ultimately the more consequential, is that Seretse is hereditary king of the Bamangwato people of Bechuanaland, studying while his uncle Naledi (Terry Pheto) serves as regent. That's already enough for the young couple's relationship to start an international incident; where things get really nasty is that Bechuanaland borders South Africa, and that territory's newly ascendant National Party of white Afrikaners, with its brand-new system of apartheid, takes none too happy a view of its next-door neighbor having a mixed-race couple ruling. And so the marriage is immediately threatened both by Bamangwato traditionalists, furious that Seretse married an outsider, and the British government trying to break the couple apart at the behest of South Africa.

No surprise that this all ends happily (it's hard to imagine that there'd be a movie at all if it didn't), though just how happily is rather extreme: Seretse Khama would take the nascent anti-British sentiment that this event stirred up, and in the 1960s would help Bechuanaland negotiate its freedom from England, helping to establish the protectorate as the independent nation of Botswana in 1965, and serving as its first elected president. Getting to that point (which the movie sums up in a closing title card) from 1947 takes an awful lot of plot, more frankly than the 111-minute feature is prepared for. And Hibbert makes some awfully odd choices about what to emphasise as a result, leading to a film that focuses on things that are rarely the most interesting or cinematic.

Bluntly, the bulk of A United Kingdom turns out to be a drama about political negotiations, which is probably the best way to tell this story if what you care about is getting things laid out clearly, to maximise the audience's "aha, I did not know that; now I do" response. This leaves, for example, very damn little time for such trivialities as the actual relationship between Seretse and Ruth (they spend the bulk of the film on separate continents, as Seretse finds himself exiled in England while Ruth endears herself to the population that so mistrusts her). Given that Oyelowo and Pike are so clearly the film's strength, any time spent away from them feels like time wasted, and particularly, it feels like a crime against art that we get so little of their dazzled courtship, the most emotionally true and engaging part of the film. The little details of giddy expressions and stolen glances as the two discuss jazz and revel in the intoxication of young romance give both actors some wonderful chances to do subtle character work (Oyelowo is never better than in the first thirty minutes; the role transforms into a stock "yell about injustice" character, and he does it well enough, but it's just inherently less interesting). The rest of the movie lacks that, though Pike manages to make the most of the character that the film spends less time with, but gives more dynamic material to.

Meanwhile, the plot and characters and actors are trapped in the gilded cage of a very nice movie: the chief thing I could say about Sam McCurdy's cinematography is that he and Asante are awfully jejune about using digital color correction to make the red sands of the Kalahari look rather suspiciously orange, under the altogether offensively teal skies. And that he makes the halls of British government look dusky, with diffuse white light, in the manner of literally every other movie of the 21st Century set in the halls of British government. It's all perfectly functional and immodestly boring, the kind of biopic that presents history as a carefully preserved museum display, rather than lending it any sort of vitality. Seretse and Ruth deserve more than that; Oyelowo and Pike deserve more than that too, and in their vigorously felt, physically expressive performances, they almost manage to force A United Kingdom to be more than that, but in the face of this much staid respectability, an actor can only do so much.

Categories: british cinema, love stories, message pictures, the dread biopic