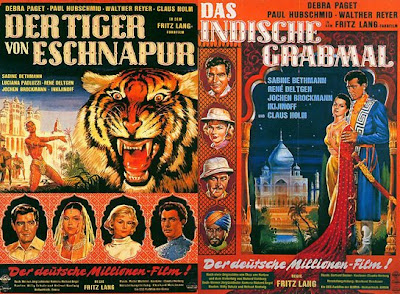

It seems a little strange to me that a major filmmaker could be attacked for making an escapist adventure story, especially when that filmmaker had such a storied history with epic entertainments, and such a particular attachment to his material: the films were a remake of a pair of silent adventure movies from 1921, released under the series title The Indian Tomb, with a script by Fritz Lang and his future wife Thea von Harbou, from her novel. Though Lang and von Harbou would divorce after she joined the Nazi Party, the script they first wrote together would long retain a special place in his mind, and his ambitious expansion of the material was less the work of a has-been trying to make something profitable than the culmination of a career-long dream.

Still, Lang was roundly denounced for making what was seen as, at best, a high-budget children’s movie. Not that the budget was even all that high: not enough to avoid some truly awful visual effects in both halves of the series. Trashy fantasy, they called it, and wrote the director off, and in the end he’d only make one more film, 1960’s The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, before settling into a long retirement.

In these post-modern days, fifty years down the road, we’re a bit more forgiving of escapism and genre films, and it doesn’t take much effort to view Lang’s Indian epic as every bit the equal to the great adventure pictures that are uncontroversially regarded as excellent cinema: Raiders of the Lost Ark (a film that, along with its sequels, owes more than a little debt to Lang’s dyad), The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars. Though The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb are doubtlessly a bit slower-paced than those films – what film of the 1950s is not slower-paced than its modern counterpart? – they hold up exceedingly well, not just as great fun but also as great craftsmanship. For indeed, shockingly artificial tigers notwithstanding, the Fritz Lang who made these films in 1958 was the very same Fritz Lang who thirty years earlier set the ground rules for all science-fiction, and who created the world’s first masterpiece of sound cinema.

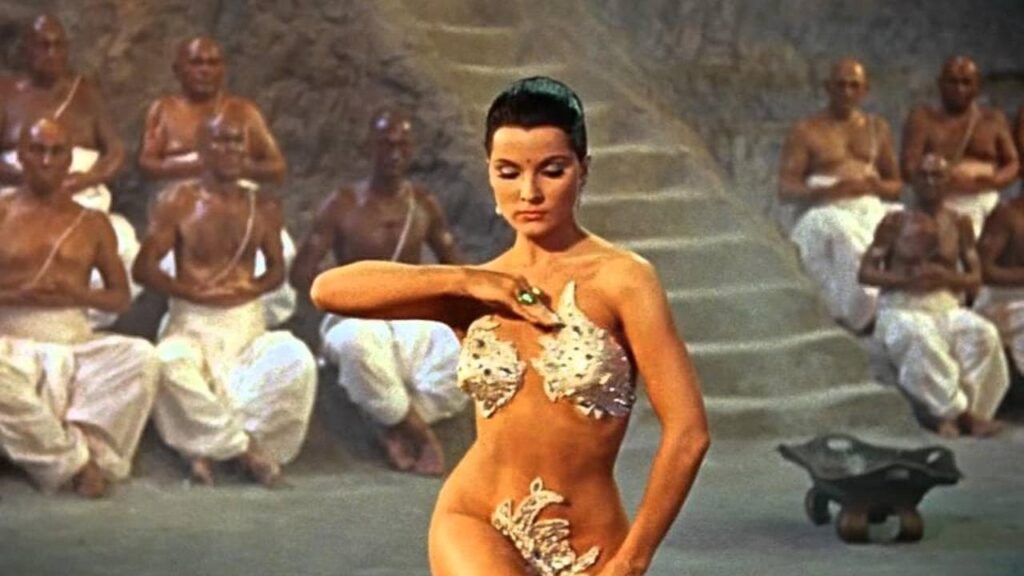

And now, the plot: Harald Berger (Paul Hubschmid) is a German architect invited to the kingdom of Eschnapur in India by the widowed Maharajah Chandra (Walter Reyer, a white actor in brownface; assume that this clause can be added after every performer’s name going forward) to design a modern complex of hospitals and schools. Along the way, Berger meets up with the beautiful dancer Seetha (Debra Paget, the requisite American star brought in to boost the film’s US box-office potential), also on her way to Eschnapur; he saves her from a stuffed tiger in the jungle, and they swiftly fall in love. This is bad for the smitten Chandra, but good for his wicked elder brother Ramigani (René Deltgen) who incorporates the secret love affair into his plans to kick Chandra off the throne. Intrigues and near-death experiences percolate until finally Berger and Seetha flee Eschnapur; and as The Indian Tomb begins, Berger’s partner Walter Rhode (Claus Holm) and his wife, Berger’s sister Irene (Sabine Bethmann) arrive looking for the missing architect, just as Ramigani’s plots kick into high gear.

Unapologetic potboiling it certainly is. And why not? A vast epic like Lang had in mind takes that much twisty plot just to keep things moving, and if there’s one thing to love about these films, it’s that the nearly 3.5 hour running time absolutely flies past. But I am not really interested in the plot, though it be packed with crocodiles and swordsmen and caves of lepers. That just means that the films meet the needs of a melodramatic adventure picture. What’s interesting – what elevates the films to the status of art-in-genre-clothing, is Lang’s ever-reliable visual sense, his taste for lurid color and perfect compositions.

Lang himself once studied to be an architect; something I only recently learned, and hopefully something that comes as a surprise to you. Aside from what this says about his choice of heroic adventurer, it suggests what had long been one of his greatest strengths, and what is easily the most compelling aspect of the Indian films: the director’s talent for shooting sets. Of course, a filmmaker who couldn’t shoot on a set would be doomed to a short and ignoble career, but Lang brings something else to the table, a geometric precision to the interplay between his actors and mise en scène and the camera lens, almost never on the same plane as the action but always at a distinctly skewed angle. In any Lang film, the abstract qualities of width and depth are at least as interesting as any other visual component of the movie, and in the Indian epic, he gets to add an important dimension to this tradition: the native design styles of India, with their tendency towards squares and repeated patterns. Not only are the sets themselves elements of the composition, the textures of the sets are, as well, and the ultimate sense is of the overwhelming power of structures and rooms, dominating the human protagonists to the point where even the paths they walk are elements of a design, rather than their own free choice.

This is not incidental: the conflicts in the movies’ story largely hinge on who is at any given point imprisoned by whom, and by making the visual framework of the films a sort of prison, this recurring plot thread is given added weight (it’s worth pointing out two things: every scene that takes place in Eschnapur is indoors, even those with large outdoor vistas in the background; and the scenes outside, though sometimes filled with their own striking imagery – Berger firing a gun into the sun near the end of Tiger is one of the great moments in either film – are never so precise as those inside). This is not subtle, nor is it meant to be, and sometimes it is damned effective either way: a shot of Seetha watching a finch in a gilded cage cuts to a shot of Chandra watching her through a golden lattice, composed exactly the same but as a mirror image – the point is obvious, but it makes Chandra a more threatening villain than a whole act’s worth of acting and dialogue.

All this, and it’s one of the most beautiful works of the ’50s, to boot. Of course, no movie filmed in India can look all that bad, but Lang and cinematographer Richard Angst bring out the rich textures and details of color of that country like hardly any European production before or since. They are rich, decadent films, about the corruption attendant upon decadence, and this may be a sly joke, or it may just be a way of making good on the films’ marketing campaign, which stressed the combined price tag more than the plot. I’m not sure that it matters why; when a movie is unbelievably lovely, that is in at least a small way its own justification.

As adventure cinema goes, the Indian epic has a lot of competition in the modern world, and most of it is certainly a lot more polished looking; but the obvious plaster sets and fake tigers and the ludicrous cobra that prominently features into the film’s unexpected erotic centerpiece are part of its charm, and not just in a “so bad it’s good” way. The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb are a potent argument that the quality of an effect is never as important as the purpose served by that effect – if we are mostly concerned that there is a tiger, we will believe an apparent forgery in service to the story, but if we are mostly concerned with how the tiger is made, the story will be soon forgotten and we end up with soulless CGI blockbusters, convincing to look at, but dead inside.

Lang’s Indian films come from one of the cinema’s greatest periods of adventure films, when effects were just good enough that you could show almost anything, and still bad enough that the filmmakers had to pull out every stop to make sure the audience didn’t laugh at the strings. It feels a lot different from an Indiana Jones picture, or a modern superhero epic, and maybe its slowness and artificiality would be deal-killers for the modern viewer. That’s a grand pity – it’s a real delight to let Lang’s dream project wash over you, taking it on its own terms and not the ones that modern marketing machines impose on film. The whole experience is a bit uneven; The Indian Tomb isn’t nearly so precisely made as its predecessor, although more happens, and it takes a good while to adjust to the film’s unique and very German mentality. But that shouldn’t detract from the films’ great achievement: they’re the ultimate matinee movies, just like their critics declared in ’58 and ’59. Happily, we know now that matinee movies are pretty much completely awesome.