The complete list

Introduction

#1-5 #6-15 #16-25 #26-35 #36-45 #46-55

#56-65 #66-75 #76-85 #86-95 #96-105 #106-115

Notable omissions

(Godfrey Reggio, 1982, USA)

Somewhere, there’s a point where pretentious, artistic, and kitschy are exactly identical to one another. If you stand at that point, and take a single step towards “artistic”, you arrive at Reggio’s wildly influential mood piece on the conflict between human progress and the environment, though the director’s unmistakably New Agey take on his theme (the title, for Christ’s sake, comes from Hopi) is not so memorable as the manner in which he presents it: a feature-length music video for a 12-part Philip Glass piece that was composed to the first cut of the movie, after which Reggio completely re-edited the whole thing to follow the musical rhythm. It would be easy to call this an unusually long experimental piece, except that the combination of music, imagery and editing, now slow and grinding, now terrifyingly abrupt, communicates the “plot” of the movie with more clarity of purpose than most features. (Reviewed here)

74. In the Mood for Love

AKA 花樣年華 (Fa yeung nin wa)

(Wong Kar-Wai, 2000, Hong Kong / France)

From my Best of the ’00s: Wong’s tribute to the secret life of the human heart is one of the most moving love stories of all time; that it’s also an unmitigated masterpiece of design and form certainly helps quite a lot. Aching with romance even though the leads (Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, two brilliant actors at their very peak) don’t even share a stolen kiss, this story is mired in an exact place and time, but its feelings are universal; the director and his many gifted collaborators create an impossibly lush, involving mise en scène that’s never indulgent and gives the movie a heady splash of glamorous sensuality. This may be the most Impressionistic movie I have ever seen; both the story and the images are ultimately driven by the abstract experience of passion, made heartbreakingly tangible through means completely unique to cinema.

73. What’s Opera, Doc?

(Chuck Jones, 1957, USA)

The high water-mark of a more elegant age, when the creators of theoretically disposable entertainment could assume that most of their audience would know enough about opera to get the jokes; on the flipside, how many thousands of American kids got their introduction to Richard Wagner from Elmer Fudd singing “Kill the wabbit”? The most ambitious Warner cartoon of its generation, the short is the culmination of that studio’s use of classical music, slapstick humor, and sarcastic post-modernism to demolish the wall between high and low culture; there may be no more pointed bit of fourth-wall breaking in American cinema, nor one that did more to normalise the idea that movie characters are aware they’re being watched, than Bugs Bunny’s wry final line, which manages to undercut operas, cartoons, and Bugs/Elmer shorts all at the same time. That it’s easily the most beautiful of all Warner shorts is just gravy.

72. Pather Panchali AKA পথের পাঁচালী

Aparajito AKA অপরাজিত

The World of Apu AKA অপুর সংসার

(Satyajit Ray, 1955, ’56, ’59, India)

In the decade when national cinemas went international, the well-established film industry of India first attracted the attention of the world at large thanks to an ambitious coming-of-age story made by first-timer Ray: his tale of a young man from rural Bengal trying to find success in the city and learning to be a man is arguably cinema’s greatest bildungsroman. Taking his cues from the Italian Neorealist movement, Ray quickly moved away from that into an aesthetic all his own: one that marries realism with a more delicate, almost pastoral feeling, in which even the grimy surfaces of Kolkata are rendered with hazy lyricism. Though Pather Panchali is by itself one of the all-time great debuts, each film is brilliant in its own way (I am marginally inclined to prefer the third), and the trilogy taken as a whole is one of the fullest character studies ever filmed.

71. Revenge of a Kinematograph Cameraman

AKA The Cameraman’s Revenge

Месть кинематографического оператора

(Władysław Starewicz, 1912, Russia)

If, almost one hundred years later, animator Starewicz’s most successful film can still seem almost dangerously unlike anything else you’ve ever seen, one wonders how it could possibly have played back when the very notion of using animation to tell a story was still somewhat novel. Unpleasantly realistic bug puppets are run through a story of marital infidelity in which things come to a head thanks to the cunning use of cinema itself – groundbreaking stuff in 1912, and still awfully compelling, particularly when married to the casual depiction of beetles and grasshoppers wearing hats, carrying briefcases, sitting down to dinner, but never otherwise being anthropomorphised: it remains freakishly unsettling, and the alienating discomfort it makes us feel still allows the simple melodrama to hit with impact unheard of in most other films at their centennial. Starewicz’s imagination remains fresh even in an age when Cronenberg is old hat.

AKA Stairway to Heaven

(Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, 1946, United Kingdom)

The Archers’ masterpiece: a luminous mixture of lurid color and glowing black-and-white (in Jack Cardiff’s first major work as cinematographer, no less!) that tells one of the quirkiest romantic plots in cinema history with such such subdued dry wit that even its most fantastic elements seem mild (the title isn’t a sign of urgency, but a statement of theme). An RAF pilot accidentally fails to die and causes an upset in the heavenly bureaucracy, and tries to prove in celestial court that he deserves another chance now that he’s fallen in love. Prefiguring everything from Defending Your Life to Wings of Desire, the film boasts some of the most tremendously creative design in history, proves that David Niven could give a top-shelf performance, and is thoroughly entertaining while giving you more to think about than most message movies: not bad for what started life as a piece of post-war propaganda.

AKA Les vacances de M. Hulot

(Jacques Tati, 1953, France)

Tati had already directed a short and a feature, both entirely saturated with his conception of physical comedy as an act of ballet, when he introduced his iconic alter-ego Hulot, and ramped up the number of impossibly perfect gags in which something as simple as the precise volume of a sound effect can make the difference between laughter and the complete absence of a joke. Taking as its subject the foibles of a whole community of seaside vacationers, caricatures rendered with sublime love and gentlenes, the film has no story more precise than “this is what it feels like to spend time at a beach resort for a little while”, with even the Chalpinesque havoc Hulot causes feeling more pleasant than destructive. Still, it’s so laid-back, and so delighted by all its characters, that it feels like taking a crash-course in what makes humanity kind and decent.

68. The Marriage of Maria Braun

AKA Die Ehe der Maria Braun

(Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1979, West Germany)

The finest of all German films to gaze steadily at the country’s rebirth World War II, and it does not very much like what it finds there. Fassbinder’s most popular film, though this is not, happily, because it is his most approachable: the story of a woman (an earth-shattering performance by Hanna Schygulla) trying to survive and thrive in the years after the war by auctioning off one piece of her soul after another is designed to function like a woman’s picture of the 1950s (when Maria, like a great many other women, was responsible for the economic righting of West Germany), but it takes its cues from Sirk in using the trappings of melodrama to investigate much darker and more socially significant themes of Germanself-identity in the ’40s and ’50s, all the way to the ’70s. Absolutely watchable, even as it refuses to offer any sentiment or comfort.

(Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1932, France / Germany)

Any mediocre horror hack ought to be able to cobble together a film with a good, murky, nightmarish atmosphere; it takes an all-time master of cinema to render a film that dispenses with the realistic and canny so successfully that the whole movie feels like its own nightmare. And that’s just what we get in Dreyer’s magnificent tribute to fog and shadows and paranormal whatsits creeping along out of side, a movie that isn’t explicitly scary so much as it is so tremendously disorienting and anti-real that the lack of grounding is, itself, the terrifying part. The remarkable use of early sound and the crooked visuals suggest an alternate-universe version of Expressionism are just different enough from virtually anything else in history that the film remains as eerie as ever: unlike horror films from even a few years ago, Vampyr plays tricks, perfectly, that nobody else has ever dared attempt. (Reviewed here)

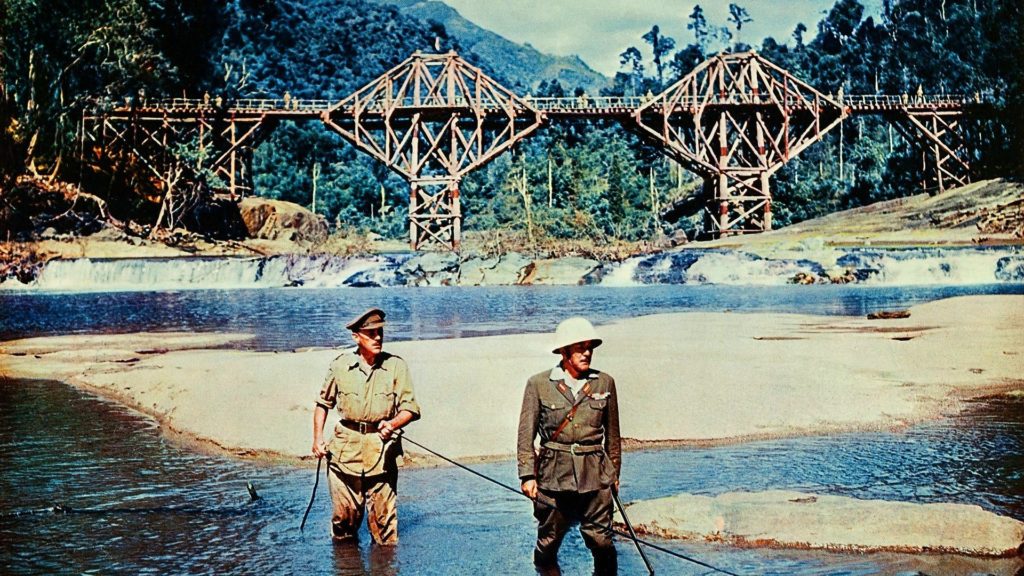

(David Lean, 1957, USA / United Kingdom)

There could be no better transition from Lean’s early chamber dramas, flawlessly detailed psychological representations of stubborn Britishness, and his later epics, gigantic panoramas that remain his best-known works, than this film which so spectacularly combines them (as would its successor). Though it’s explicitly a story of war, of missions and plans and armies and big explosions, the heart of thing is pride driving men insane: men like Col. Nicholson (Alec Guinness, in his best performance) and his Japanese mirror image, Col. Saito (Sessue Hayakawa), the embodiment of all their country’s most jingoistic cultural clichés, who by the end of the film have sacrificed all other concerns such that it’s hardly fair to say which of them remains “the good buy”; and in the final moments, Guinness’s portrayal of the moment when Nicholson wakes up, makes it clear that the tragedy here is one of the mind, not of combat.