The complete list

Introduction

#1-5 #6-15 #16-25 #26-35 #36-45 #46-55

#56-65 #66-75 #76-85 #86-95 #96-105 #106-115

Notable omissions

55. Stagecoach

(John Ford, 1939, USA)

There are, broadly speaking, two kinds of Westerns: the ones that probe the cracks of the genre and call its tropes and morals into question, and the upbeat ones that created that genre in the first place. Of this second sort, the best ever made is Ford’s first trip to Monument Valley, as well as the film that turned John Wayne into one of the all-time biggest movie stars, and simply one of the best-constructed and most entertaining adventure pictures ever. Not to say that Stagecoach doesn’t push its generic boundaries to the limit, making a typically Fordian tale of how the “Good People” are often just sanctimonious jerkasses, and it’s the whores and rascals that actually deserve our respect; but that’s secondary to its perfection of an iconic vision of the West that has remained durable – intractable! – for four generations of moviegoers. (Reviewed here)

54. Spirit of the Beehive

AKA El espirítu de la colmena

(Victor Erice, 1973, Spain)

The exhilarating feature debut of a director who apparently proved everything he ever wanted to, given that he’s made all of four movies – two of them shorts! – in the intervening decades; but if your first feature was as all-round perfect as Erice’s, maybe you’d think about retiring immediately, as well. A warm portrait of the last days of childish innocence, it manages the rare feat of perfectly evoking the perspective of its seven-year-old protagonist without condescension (Ana Torrent is one of the most amazing on-screen children I’ve seen), and without asking the adult audience to feel tragically more mature than she is. With its rapturous golden hour photography, hushed long-takes, and sublime reminder of the youthful experience of seeing a movie as a snapshot of an alternate universe, this is the finest and most beautiful of films about childhood: wrapped in nostalgia but deathly serious about its subject. (Reviewed here)

53. Annie Hall

(Woody Allen, 1977, USA)

The bravest romantic comedy ever made: what earlier film presented its central relationship as funny and satisfying and still it’s pretty much a good thing that they didn’t end up together? It’s the surest sign of what Allen got right that a number of the film’s lines have ended up as cultural shorthand (“A relationship is like a shark”; “We need the eggs”), but Annie Hall‘s brilliance isn’t just that it’s more grown-up than any other mainstream film about relationships. It’s a masterpiece of structure, starting after the end and presenting the story of its central lovers all out of order, the way you might remember it if you were trying to figure out what went wrong after the fact. And it’s decoupage-like form, subtitles and animation and all, evokes with military precision the mind of a man who deals with his pain by burying it in sarcastic jokes.

52. Sherlock Jr.

(Buster Keaton, 1924, USA)

A parody of the whole concept of movies, from their production down to the act of watching them, Keaton’s thrillingly modern piss-take on the medium that made him a star is certainly neither the first nor last satiric meta-movie, though it is arguably the best. That said, all post-modern theoretical work and no goofy slapstick play makes Buster a dull boy, which is why we can be thankful that the director/star’s most intellectual work is also among his most delightful: the climactic chase scene alone would surely make this a timeless slapstick masterpiece. And with a running time so brief, we could well use this as the yardstick dividing “features” from “shorts”, Keaton’s legendary talents are presented here in a compact blast of creative energy, with the most non-stop barrage of laughs and staggering “he didn’t really do that?” athleticism of any major silent comedy. (Reviewed here)

51. Barry Lyndon

(Stanley Kubrick, 1975, United Kingdom / USA)

More than any filmmaker, Kubrick didn’t like to repeat himself; still, I can’t imagine that many people were expecting him to come out with a richly detailed costume drama, at least not until they got to see the finished work. Set in a version of Georgian England at once icily static and unnaturally real – John Alcott’s extraordinary use of natural and faux-natural light to replicate the “actual” look of the 17th Century is perhaps the most technically accomplished cinematography ever – the director found a way to make Thackeray’s biting assault on aristocratic mores even nastier, thanks in no small part to the deft application of actors, particularly star Ryan O’Neal, cast exactly because he didn’t have the talent to suggest Barry’s inner life. Along with a visual style based on period paintings, the whole thing is both highly artificial and grubbily human, not unlike the milieu it presents. (Reviewed here)

50. Psycho

(Alfred Hitchcock, 1960, USA)

Not to get hyperbolic on y’all: but there is cinema before Psycho, and cinema after Psycho. As surely as the concurrent French New Wave, Hitch’s unprecedented story of violence with that corker of a mid-point twist demolished and re-wrote everything that anybody knew about film narrative, and he didn’t have to get all theoretical to do it, either; can you imagine even the most daring mainstream Hollywood director playing that kind of dirty trick on the audience today? That achievement is itself sufficient to carry the movie to movie history’s top tier even the face of a dodgy third act, but it certainly doesn’t hurt that the first half boasts some of the most unendurable tension and paranoia of any thriller from any period: even without knowing what’s going to happen, watching poor Marion Crane get put through the wringer like she is the very stuff of nerve-wracking genius. (Reviewed here)

49. The Battle of Algiers

AKA La battaglia di Algeri

(Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966, Italy / Algeria)

If you’ve ever seen a narrative film use documentary techniques for “added realism”, then you’ve seen a film that owes a irredeemable debt to Pontecorvo and DP Marcello Gatti, who didn’t invent that trick but assuredly perfected it in this political broadside, cinema’s greatest work of anti-colonialism. We’d all be much better off if message movies, whatever their ideology, were all this confrontational: far from trying to convince you that they’re right through sensibility and pragmatism, the filmmakers unleash a primal scream of violence and rage against an unjust world that first allowed one nation to grind another under its heel, and then required the victims to resort to such savage, animalistic tactics to regain their dignity as human beings. Shorn of all unnecessary delicacies that usually adorn historical dramas, The Battle of Algiers is a ugly story that nonetheless burns with a fierce love of humanity in every frame. (Reviewed here)

48. Pinocchio

(Hamilton Luske & Ben Sharpsteen, 1940, USA)

Snow White is more important; Fantasia is more ambitious and wide-ranging; but for my tastes, nothing showcased the possibilities of Disney animation as both a storytelling medium and as breathtakingly beautiful visual art as this fable of a puppet who wants to be human, and is subjected to danger and darkness and cruelty unimaginable in a family film today on the way to getting his wish. Anchored by one of the very finest original soundtracks ever written for a movie musical, Pinocchio is by turns sweet and harrowing, giddy and heartbreaking, ending in the most deserved happy ending of any Disney picture. Meanwhile, the impressively fine linework, fussy backgrounds, and enveloping use of color, atop the character animation by Disney artists at the peak of their abilities, gives the film the aura of of a moving oil painting, lending an elegant classicism and timelessness to the fairy tale plot. (Reviewed here)

47. The Double Life of Véronique

AKA La double vie de Véronique

(Krzysztof Kieślowski, 1991, France / Poland / Norway)

A heady mixture of Sławomir Idziak’s warm-as-a-blanket dreamscape cinematography, Zbigniew Preisner roiling chorale score, and Irène Jacob’s miraculously simple performance(s) as two women who might be the same woman, or two women who might share one soul, or just two women at the heart of a real heckuva coincidence. Occasionally read as a metaphor for Poland’s relationship to Western Europe, but I find that reductive; there’s already quite enough to chew on and find hypnotically engaging in this depiction of the human spirit seeking joy and security and finding… both? neither? Part of the delight of Kieślowski and Krzysztof Piesiewicz’s screenplay is its refusal to tell anything, instead inviting the viewer to respond to their metaphysically dense scenario in whatever way seems personally appropriate. And if that sounds like too much work there’s always the completely sensual joy of how ravishingly beautiful the movie looks and sounds. (Reviewed here)

46. The Last Laugh

AKA Der letzte Mann

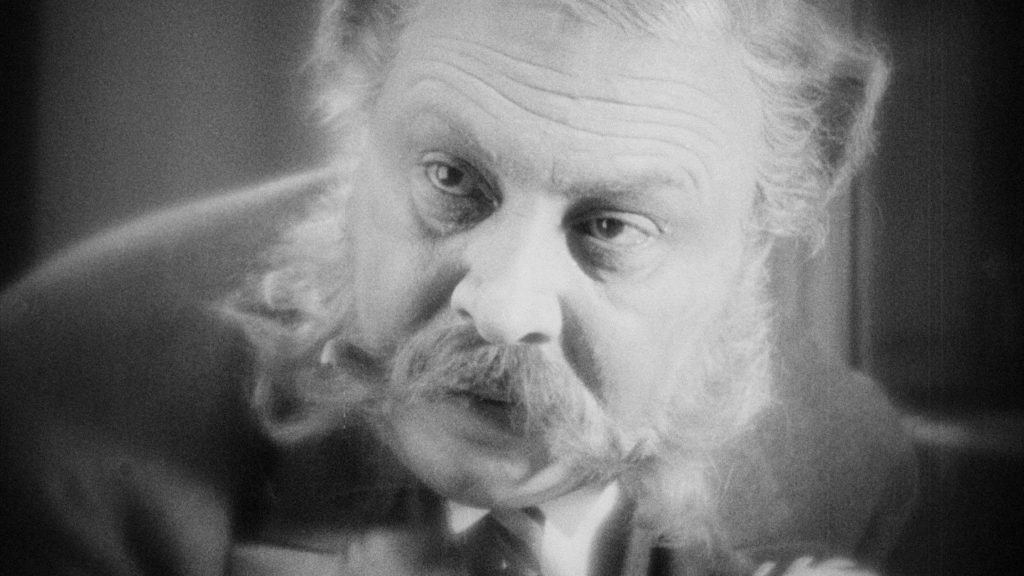

(F.W. Murnau, 1924, Germany)

A proud doorman at a swanky hotel is humiliated when he’s demoted to washroom attendant, and attempts to hide this fact from his family and neighbors to avoid losing face. Sounds kind of idiotic, but with the doorman played by the great Emil Jannings at his very best, and directed by Murnau, a man with a freakishly intuitive grasp of how to use cinema language, this silly scenario results in one of the great emotional sucker-punches of the silent era. Always looking for new ways of expressing his stories visually, Murnau refined the use of the tracking shot to levels previously unimagined to draw the audience into the film and right up to the protagonist’s weary face; even today, there’s a pointed gracefulness to the camera movements here that remains stirring and effective; but technical accomplishments aside, the heart of the movie, in 1924 and now, is Jannings’s crushing performance.