Day & Night (Teddy Newton, USA)

Screened fifth in the Shorts International program

I can’t do better than snip some thoughts from my full-length review:

“The most impressive short-form piece that Pixar has put out…

“Newton’s ability to finesse a remarkably difficult conceptual hook into a supremely easy cartoon is proof enough that he has storytelling skills much the equal of anybody working at Pixar. Yet this is also, possibly, the least of the film’s achievements: it is technically, formally, and thematically a work of great accomplishment, and merely being able to tell a weird story coherently is just cake at that point…

“I’m more than happy to argue that Day & Night is the present masterpiece of 3-D cinema; Coraline uses 3-D in some amazing ways, no doubt, and for all their gimcrackery, Avatar and TRON: Legacy certainly understand the way to wring jaw-dropping spectacle out of the technology. But none of those have done such a fine job as Day & Night at using 3-D to deepen the meaning of the film, please forgive the inadvertent pun. Day & Night in 2-D is an excellent piece; Day & Night in 3-D is rapturous, building a world like nothing else I’ve ever seen…

“However trite the “Don’t judge others” moral might sound, and however unoriginal it no doubt is, it’s unfortunately also a moral that remains absolutely fresh after thousands of years, and projects like Day & Night will continue to matter as long as human beings are human beings.”

And of course, it remains my favorite film of the year, short or long or otherwise.

* * * * *

The Gruffalo (Max Lang & Jakob Schuh, UK)

Screened third in the Shorts International program

A wonderfully genial, affable family movie with a sweet, lilting script of rhyming couplets delivered by a bunch of top-shelf British ringers: Helena Bonham Carter as the mama squirrel narrator, Tom Wilkinson, John Hurt, Rob Brydon, and Robbie Coltrane as the assorted villains, James Corden (who, okay, I’ve never heard of) as the plucky mouse hero. And a criminal 27-minute running time (the longest of all ten non-documentary shorts) that threatens to turn something genial and affable into something painful and grueling.

The story has whiskers on it, and not by accident: a mouse journeys through the woods, outsmarts predators with tales of something called the Gruffalo, and then bumps into the very same Gruffalo that he thought he’d invented. It’s mostly harmless, awfully sweet, and I suppose it’s possible to dislike it if you are a completely awful human being. At the same time, I can’t imagine anybody actually falling in love with it, unless they are eight years old. But you know what? The world needs great movies for eight-year-olds just like it needs great movies for the rest of us. But Christ, I wish it were shorter.

The CGI animation is palpably meant to evoke stop-motion, and this is the second great problem with the film: for while it’s probably fair to say that it “evokes” stop-motion, it doesn’t really look like stop-motion, so much as it looks like CGI ineptly aping the texture of stop-motion. This is a particular shame since the animation is, in every other way, quite lovely: I was particularly entranced by the character animation of the mouse, whose expressions change in strikingly subtle ways to communicate his thoughts with the tiniest – yet clearest! – of visual cues. It’s outstanding work, only somewhat obscured by the unlovely tension inherent in the film’s earnest desire to hide its digital nature. But that’s a conceptual choice, not a matter of inexpert execution, and I am most eager to see the next project this team works on – hopefully one that clocks in at, maybe 10 minutes or thereabouts.

* * * * *

Let’s Pollute (Geefwee Boedoe, USA)

Screened second in the Shorts International program

The only film in the whole batch that I didn’t like (an excellent improvement from last year’s dodgy slate), Let’s Pollute is an agonisingly facile satire of consumer culture and the environmental impact of manufacture. A theme for which I have a special fondness, and I am reminded once again of my favorite Daniel Dennett quote: “There’s nothing I like less than bad arguments for a view that I hold dear”. Let’s Pollute is a tremendously bad argument, one whose grating snarkiness offers no answers or insight deeper than “boy oh boy, aren’t you and I both outstandingly superior for the beliefs we hold?”

Fashioning itself tonally as one of those ’50s rah-rah shorts where a jolly narrator (Jim Thornton) exhorts us to do this or that bit for the betterment of America, the film attacks pollution using the dread weapon of sarcasm: it piles on one example after another of how you, dear viewer, can do an even better job of tearing through natural resources and ruining the world, because that’s the American way. That’s all. That one joke, repeated and repeated for a blissfully short six minutes.

This much must be said for the film: the visual style absolutely pops. My instinct tells me it was animated in Flash, or something very similar; but the images are all modeled to look like pencil and chalk sketches, very much in the clean, minimalist style of UPA’s work in that company’s post-WWII heyday. It’s bright and fun to look at, which is great, because it’s otherwise about as far from fun as you can get without catching something dreadful and oozing.

* * * * *

The Lost Thing (Shaun Tan & Andrew Ruhemann, Australia)

Screened fourth in the Shorts International program

Far less hectoring than Let’s Pollute, The Lost Thing ends up troweling on its theme with just as much of a heavy hand, though it’s mostly all bunched up at the very end.

That theme, if you’re curious, is approximately, “In an increasingly automated life, we lose sight of the odd and beautiful things, and THAT IS VERY BAD.” We get there when a young man (Tim Minchin) finds a huge thing on the beach, somewhat like a big metal shell for whatever Lovecraftian assortment of tentacles keeps poking out. The boy and thing quickly become friends, but the boy just as quickly realises that he can’t keep the thing safe, and begins looking for a place where it can be at peace.

The story, honestly, is well and truly beside the point: what lingers in the film is its extraordinary world-building, somewhere between Proyas’s Dark City and Gilliam’s Brazil in its evocation of peculiar future-shock landscapes and faceless bureacracy and a stunning lack of individuality. That lack is nowhere felt in the movie, one of the most visually unique animations of the last couple of years; the intricacy and complexity and lived-in perfection of this world that we get to understand quite intuitively in just 15 minutes is so overwhelming that I can even overlook the frankly unpleasant character design, where every human has skin that appears to be fashioned from butcher paper.

If, in the end, The Lost Thing has very little to offer besides its remarkable visionary take on the future of bureaucracy, that’s more than a lot of animated shorts can claim. It’s a world that I’d happily return to, for whatever story the filmmakers wanted to tell; any excuse to goggle at that design would be as good as the one we’ve already got here, and probably a lot better.

* * * * *

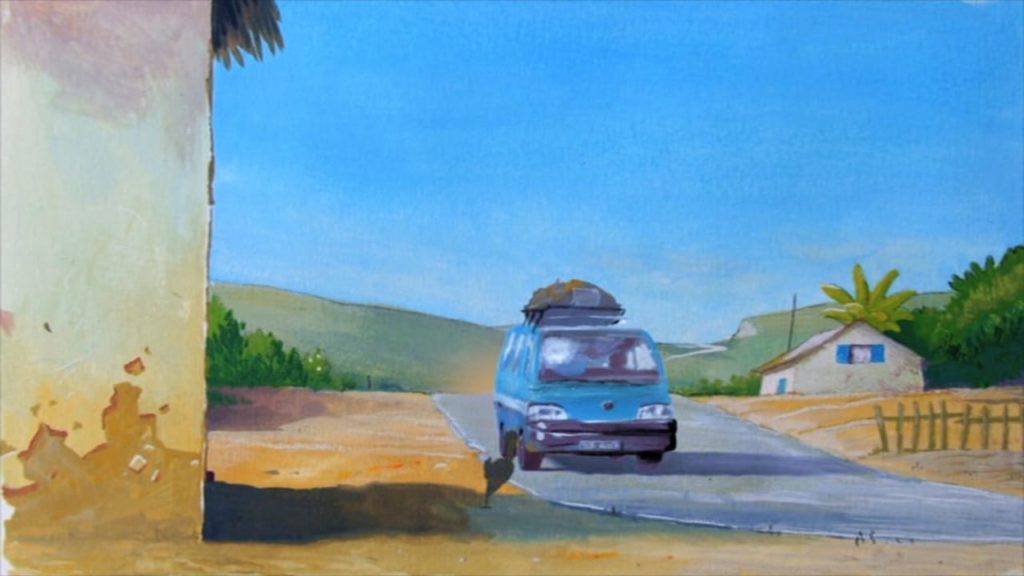

Madagascar, carnet de voyage (Bastien Dubois, France)

Screened first in the Shorts International program

The most frivolous story of all: for indeed, calling what Madagascar possesses as its plot a “story” is doing a disservice to hundreds of years of world literature. What we rather have here is a series of attempts to capture a trip through Madagascar – the title translates as something close to “Travel Journal”, and that’s exactly what it is.

But Good God Almighty, what a travel journal! Dubois and his team of animators use every style you can think of: pencil sketches, photos, watercolors, gouache paintings. That is to say, they use the computer-generated version of those things, to capture all the impressions of a European’s trip through a few cities on that African island, with most of the film being given over to a funeral ceremony. Then, those drawings and paintings and so on are turned into 3-D CGI models, so that they can move like fully-dimensional objects. It’s a mixed media collage of 3-D imagery that looks like moving paintings – I can barely describe it in any way that makes much sense at all, but is the boldest and most imaginative animation I have seen in a very long time.

It’s also wearying, and while at first I found myself thinking that this is what we were promised & didn’t get with Tangled, by the end of Madagascar‘s 11 minutes, I was grateful not to have to deal with a whole feature of that. Too much stimulation; it’s almost too much at 11 minutes, in fact, and the only real criticism I have of the film is that it makes its point, thematically and aesthetically, by its midway point. And the funerary material could easily have been reduced. But those are small, petty points. This is a magnificent experiment that almost justifies the trip to see the whole set of shorts just by itself.

* * * * *

Two other films (“Highly Commended”) are being screened, to pad the slate out to something long enough to justify charging feature prices:

Urs (Moritz Mayerhofer, Germany)

Screened sixth in the Shorts International program

In a village in the mountains, a burly man and his aged, crippled mother are just about the only people left. So he straps her to his back and tries to climb to the next valley, where there are people & life. That’s the plot of this 10 minute fable, but it’s only even a little bit clear what the hell is happening when it’s all over; for most of the film, I was trying to figure out what the dead sheep had to do with any of this, and if a bear was ever going to show up.

When all is said and done, Urs is chiefly a demonstration piece for the student animators to show off their skills, and in that respect it largely works: like Madagascar, it’s self-evidently an attempt to create a 3-D version of 2-D graphic art, and not necessarily any more. Unlike Madagascar, that attempt is not wholly successful: there is a fatal disconnect between the texture of the characters and the texture of the backgrounds that’s only truly apparent in motion, but is nastily distracting, like an itchy tag at the neck of your shirt.

No doubt about it, the short is striking and the gorgeous mountain scenery is dramatic as all hell; but it doesn’t add up to very much. As a tech demo, it’s beautiful and shiny, but as a movie it’s just sort of… there.

* * * * *

The Cow Who Wanted to Be a Hamburger (Bill Plympton, USA)

Screened seventh in the Shorts International program

It’s a Bill Plympton cartoon; that says most of what needs to be said. If you are unaware of the man’s work, this means: a slightly sick, slightly witty narrative married to a primitivist drawing style that some of us love beyond all reason, and some of us don’t. I’ll say this: it’s a tremendously awful introduction to the man’s work. While most of his best-known and best-love cartoons, including the legendary Dog tetralogy, are sketched colored pencils, at a fairly low frame rate, The Cow… is drawn in thick, heavy lines with eye-searing primary colors (“Plympton discovered MS Paint”, I wrote in my screening notes), at a practically non-existent framerate, with the illusion of movment created by jiggling the individual drawings like the camera operator was on a caffeine bender.

The result is far more visually tiring than most of Plympton’s films, which is a horrible shame: the cheery, bright colors are a fascinating addition to his style, and the story is one of the best I can think of in his whole career. A calf sees a billboard for a hamburger company across from the field where he grows up, and convinced that this is the best life a cow could ever hope for, dedicates his life to become everything that the meat factory men look for, over his mother’s terrified objections. When he finally enters the meat factory, he learns the tremendous error of his ways, in furiously agitated pantomime typical of the animator’s work. It’s a clever, pointed satire of advertising and its effect on children that never once comes out and says that’s what it’s doing; the polar opposite to a screamingly obvious tract like Let’s Pollute. And while I pretty much enjoyed it and would imagine that anyone who has enjoyed Plympton in the past will continue to do so, there’s just no downplaying the degree to which this is a hard movie to look at, pure and simple.