JEFFERSON IN PARIS (James Ivory, France/USA)

Screened in the main competition

The first James Ivory/Ismail Merchant/Ruth Prawer Jhabvala joint after the pinnacle achievements Howards End and The Remains of the Day is nowhere near their equal. Jhabvala’s screenplay suffers from some jarring attempts at slave vernacular, particularly in the massively unnecessary framework narrative. And it’s obnoxious for a movie whose primary theme is that the Great White Men of history could be led by their maleness and their whiteness into morally dubious dead ends to show such little interest in the inner lives of anyone who isn’t Thomas Jefferson himself. But it’s not half-bad, even so: this was Merchant Ivory near its peak ability to recreate long-gone European culture as a living thing without needlessly modernising it, and the period trappings are totally absorbing. Better yet, the seemingly miscast Nick Nolte is a fine Jefferson, articulate and dignified even as he’s increasingly wracked by the gap between his place in history and his limitations as a human being. It is, however, at its worst when it’s at its most socially conscious, which feels exactly wrong. 5/10

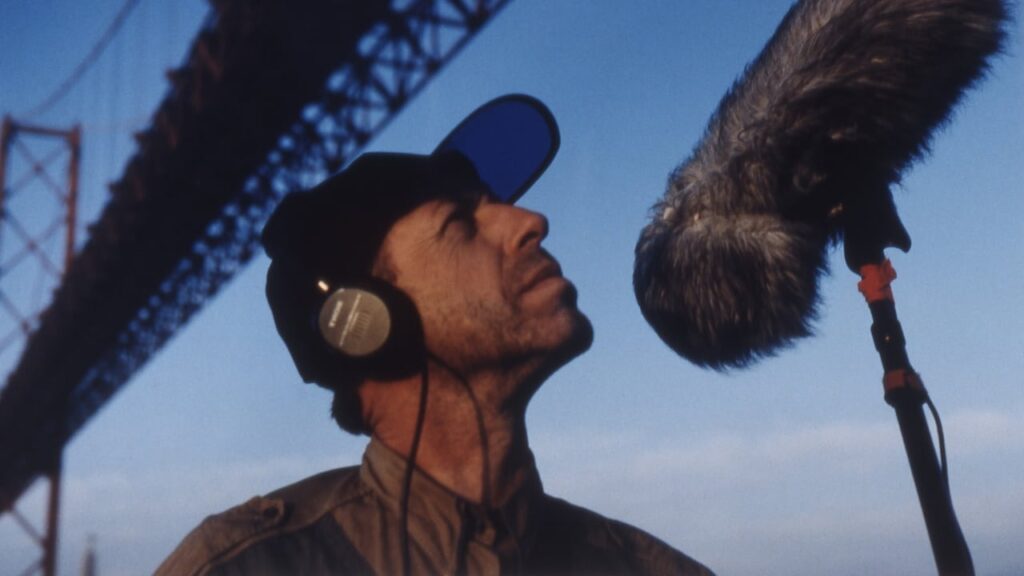

LISBON STORY (Wim Wenders, Germany/Portugal)

Screened in Un Certain Regard

Pridefully straddling the line between “way too damn pretentious” and “just the exact right amount of pretentious”, Wenders’s opaquely self-referential film follows a film sound recordist to Lisbon, where he finds a director has gone missing, leaving behind a series of fragments that begin to coalesce into a project as he finds more of them. Though a project describing what, exactly, is hard to say. Lisbon Story is something of a misnomer; a giddy valentine to Lisbon’s architecture, street layout, and music scene it certainly is, but a “story”, not quite as much. Rather, it’s a formal self-examination of how sound and image communicate in cinema, particularly as it pertains to music being used as a free way to score some emotional points; and also of the way that all movies are made out of disconnected pieces collected without the participants being able to tell what’s going on. It’s not always successful, but it’s boundlessly ambitious. If that sounds too heavy, it’s also a gorgeous travelogue that makes Lisbon as visually enticing as any European city in modern cinema. 9/10

TO DIE FOR (Gus Van Sant, USA/UK)

Screened out of competition

Two decades later, the revelatory central performance – ohmigod, the model-gorgeous Nicole Kidman, trophy wife of Tom Cruise, can act???!!! – isn’t remotely as revelatory, which does harm the project’s overall sense of cutting insight. Even in 1995, the idea that people would do anything to be famous on TV, up to and including inventing their entire personality and arranging the murders of those close to them, wasn’t exactly fresh, and while Kidman’s brightly acidic comic turn makes that message feel a bit sprier and nastier than it might, we’ve seen her do many better things since. That all being said, it’s still nice to see a black comedy that pulls so few punches, and the saucy, heavily ironic structure, with its reiteration of the primacy of television news as a sacred totem even for the people most actively damaged by it, adds a layer of smart cruelty. It is, at any rate, still the most satisfying of Van Sant’s studio pictures, sacrificing neither a sense of genre experimentation nor intelligently applied style. 7/10

3 STEPS TO HEAVEN (Constantine Giannaris, UK)

Screened in Directors’ Fortnight

“The made-for-TV erotic thriller that played Cannes” is one of those phrases that you don’t expect to have to whip out, but here we are, with one of the 1995-est movies ever. Suzanne (Katrin Cartlidge) is convinced that her boyfriend Sean has been murdered, and she dons a series of disguises to track down the individuals who were with him the night he died. Often enough that it would feel disingenuous not to mention it, we see large portions of her nude body. There’s certainly all the tackiness you’d expect from this mix of ingredients, though the filmmakers put some discernible effort into blasting the scenario apart through an application of erratic, curiously effective style: time-lapse and speed-ramping, startling camera angles, and the representation of the protagonist’s mind as a découpage-like spread of photographs. None of this overcompensating makes the film less tawdry (or bizarrely gay-baiting), and Cartlidge is a black hole where the film needs a heart, or at least a brain. But the snappy energy keeps it from being an absolute bore. 5/10

The main competition film THE SNAILS’ SENATOR, directed by Mircea Daneliuc, is not currently available in an English-friendly form