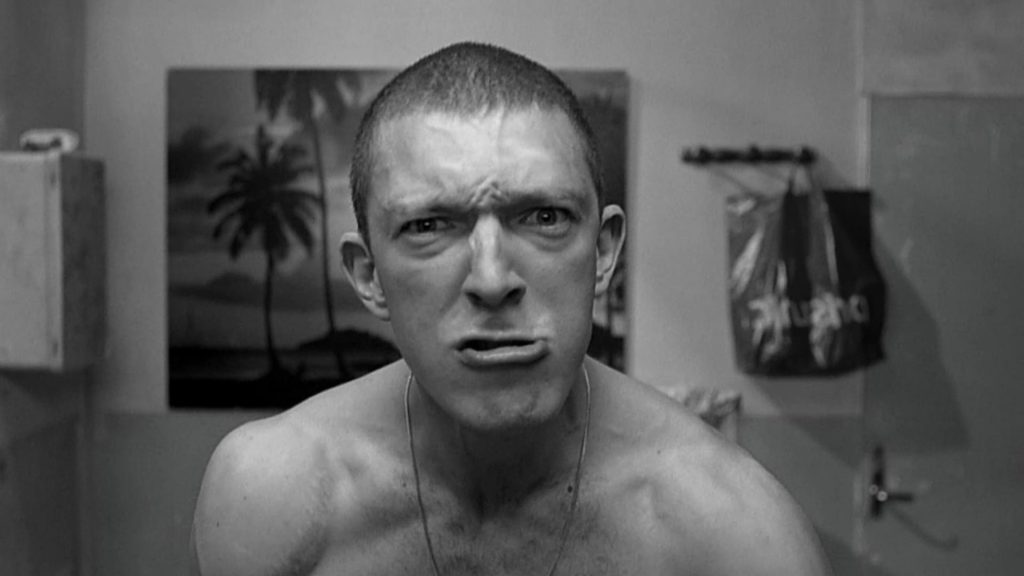

LA HAINE (Mathieu Kassovitz, France)

Screened in the main competition

A snapshot of urban race relations that, in its youthful rage, its mixture of quotidian life and political urgency, and elements of its style, is easy to summarise as the French Do the Right Thing. The film’s brazen success at message-slinging even lives up to that comparison, though it also suggests, rightly, that La haine isn’t the most original thing out there. Vincent Cassel, Hubert Koundé, and Saïd Taghmaoui are magnificent as the three buddies whose casual wanderings form a window into life both as a playground for bored twentysomethings and an impoverished hell where institutional violence and ethnic tension are constantly present, while the razor-sharp black and white cinematography (while it risks putting a glossy, romantic spin on the material) pays off far more often than not in accentuating the rough textures of the banlieues. The juvenile energy sometimes leaves the film stranded in go-nowhere scenes and the ending is overdetermined, but this is potent enough that Kassovitz’s premature Best Director nod from the jury is easy to understand, if not endorse. 8/10

DEAD MAN (Jim Jarmusch, USA/Germany/Japan)

Screened in the main competition

I’ll own up to my biases: this was my first Jarmusch film and perhaps for that reason has always been my favorite. I’d also readily declare it the best film I’ve seen from the whole of Cannes 1995, sidebars and all. A fatalistic fable about America’s love of mythic violence that finds a mortally wounded accountant traveling through the Wild West in the best cinematic approximation of Pilgrim’s Progress I’ve ever seen. Robby Müller’s freakishly great cinematography – maybe the best work of a legendary career – uses silvery metallic black-and-white to strip the landscape of its romance and amp up the feeling of otherworldly spirituality; Neil Young’s blanched-out guitar riffs that service as a score lend a jarring contemporary touch that beautifully accompanies Jarmusch’s rancid humor. It’s top-notch anti-Americana, and the only revisionist Western you really need; you can count on your hands the number of movies, irrespective of genre, that do a better job of lacerating Hollywood’s beloved cultural myths while replacing them with new myths and metaphysical philosophies all its own. 10/10

HARAMUYA (Drissa Toure, Burkina Faso/France)

Screened in Un Certain Regard

There aren’t enough sub-Saharan African films that get any kind of meaningful exposure in the Euro-American cultural sphere for it to make any sense to call any of them over-familiar. That being the case, Haramuya is not by any means an adventurous game-changer in its story or its technique. It’s a low-key slice-of-life story of a Burkina Faso town uncomfortably balanced between tradition and Westernised modernity, with a particular family being caught up in the tension between honoring the old ways and knowing when to abandon them as unworkable and choked off. Toure’s direction is exceedingly, winningly generous, refusing to blame any of the characters for latching onto the worldview that seems right to them, and presenting the frayed attitudes of the townspeople with observational warmth that feels apart from the community but also speaks to a great comfort and familiarity with them, or real-world people like them. The overall effect is much too muted to pretend that this is, by any imaginable definition, “essential cinema”, but it’s insightful, humane work even so. 7/10

THE ENGLISHMAN WHO WENT UP A HILL BUT CAME DOWN A MOUNTAIN (Christopher Monger, UK)

Screened in Un Certain Regard

The title has more of a personality that the film it’s attached to. It’s your basic genial and utterly generic exercise in letting Hugh Grant do his Hugh Grant thing against a backdrop of Colorful British Eccentrics, a form that was just about to launch into the stratosphere. Visiting a Welsh village in 1917, an English surveyor declares to the zany locals that their beloved “mountain” is in fact just a 984-foot-high hill, leading them to enact a plan to… well, I can’t hardly spoil the movie any more than it already has. As the leader of the indignant Welsh, Colm Meaney (who is Irish, we are compelled to point out) provides a much needed dose of live-wire prickliness, and I admire the dry irony of the bedtime story narrative framework, but that’s pretty much all that the movie can claim for itself. Removed from that early moment when he as still just a new transatlantic curio, Grant’s bumbling and stuttering has lost most of its charm, but there are worse examples of the form. 6/10