Editor’s note: A while back, you may recall, we announced an Alternate Ending Writing Workshop, in which a limited number of respondents were invited to brainstorm ideas for articles about films and film analysis, with editorial nudging from myself, en route to the final hurdle: putting that article in front of the faces of readers all over the internet. It took us a lot longer than we expected, but here, at last, is the first fruit of that labor, a piece by Nick Leach on one of cinema’s biggest dogs. Feel free to share any constructive criticism you have in the comments – as long as it’s constructive.

Take it away, Nick!

by Nick Leach

It goes without saying that Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is a masterpiece. What elevates it above most genre horror films is the amount of care and control of all its formal elements. The film uses not just dialogue and performances to develop its characters but also its visuals to give us a wealth of information. Everything from lighting, art direction, and the mise-en-scene of the cinematography reveals more depth to the characters and the film’s themes. When most think of formal techniques in Psycho they often think of the renowned editing in the shower sequence. But the quieter moments, especially the scene taking place in the parlor before the murder, are just as great in terms of technique. This sequence of the film also presents a perfect exploration of the film’s main theme, the evil and madness lurking underneath everyday normality, personified in its murderous killer. I will take some time to examine this scene and showcase the brilliance of the film’s overall artisanship.

This should go without saying, but just in case this is your warning: I’m about to spoil the crap out of this film and I’m writing this assuming you know how everything ends. If you haven’t seen Psycho yet, catch it as soon as you can. It’s just one of those movies that anyone with a slight interest in the medium must see. Even if you don’t like older films, I still whole heartily recommend it. For those wanting to follow along, I’m beginning around minute 34. Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) has already met the motel owner, the non-threatening Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins). But as we shall see, the warning signs of Norman’s true intentions were right there in front of us the whole time.

This is a great medium shot of our two characters. Marion moves from the foreground to the same plane as Norman, drawing our eye to the parlor entrance. The interior of the parlor is nothing more than a black void that boldly stands out. It is even more accentuated by the lovely contrast with the bright white pitcher on the tray. Where a character lives and how they choose to accommodate themselves says a lot about who they are. As Norman is letting Marion and us as the audience in his parlor, he is letting us into his interior mental space. Norman is new to us and we have only seen his “performance” as an innocent motel manager. The rest of him is hidden in the abyss of his mind, just as the parlor is hidden in darkness.

Norman enters, and nothing can really be seen in the darkness; just shadowy forms. So, he turns on the lights and thus reveals himself. Marion looks around the room and the film cuts to the objects she sees: a bunch of stuffed birds.

Birds have a lot of symbolic weight in Psycho. It isn’t that big of a leap to connect a serial killer with birds of prey. Birds also don’t have the range of emotions that say a dog or chimpanzee would have that we can easily sympathize with. As this sequence of the films continues, the connection between Norman and bird-like behavior will be made clearer. The fact that these birds are dead and stuffed adds another layer. Norman, in standard movie killer idiom, in a way likes to play with dead animals, has a fascination with death, and likes keeping these trophies around. As we later see at the film’s end, Norman’s mom is in the basement, a kind of stuffed bird herself.

Norman sets up dinner and what follows is a conversation done in a standard shot-reverse shot pattern. The way Norman and Marion are framed in their respective shots gives us a wealth of visual information. Of course, the dialogue and performances are top notch and this whole conversation can be appreciated on those levels alone. We get that great line early on here: “You eat like a bird;” again keeping the subtext on predators and prey. But the shot choices are remarkable in how they reveal character.

The back and forth doesn’t change between these two shots until the only absent character, Norman’s mother, is brought up. Norman’s speech about “private traps” is very revealing about himself and says more about him than anything in the film’s awkward coda with the psychologist. Marion is oblivious to any of the subtext here, interpreting his words to her own context; screwing up her life with the stolen money. She turns the conversation away from herself and onto how Mrs. Bates speaks to Norman. In fact, the exact moment when Marion says “she,” the film cuts to our next shot:

And “she” is very present here. Now we have a closer profile shot of Mr. Bates. This is purposefully jarring compared to the previous eye level shots to draw our attention to what is behind Norman. In the upper corner of the room is a large stuffed owl with its wings outstretched as if it was ready to swoop down and attack Norman. Owls are often associated with the night and this choice of bird is significate because it metaphorically ties back into the internal darkness of Norman’s true nature. More importantly it represents Norman’s mother or rather his idea of his mother that lives inside his mind. Just like the owl behind him, Norman’s psychotic dark side is behind his performance to Marion.

Now whenever the film cuts back to Marion, her shot is now much closer. As apposed to the previous medium shot of her on the couch, it is now a close-up. This does two things. Firstly, focuses our attention on the performance; allowing us to see Marion’s reaction to the Norman’s background story. It also again reinforces our identification with Marion. She like us is now captivated by Norman’s tale and both of us (meaning Marion and film viewer) must decide what to make of this strange man.

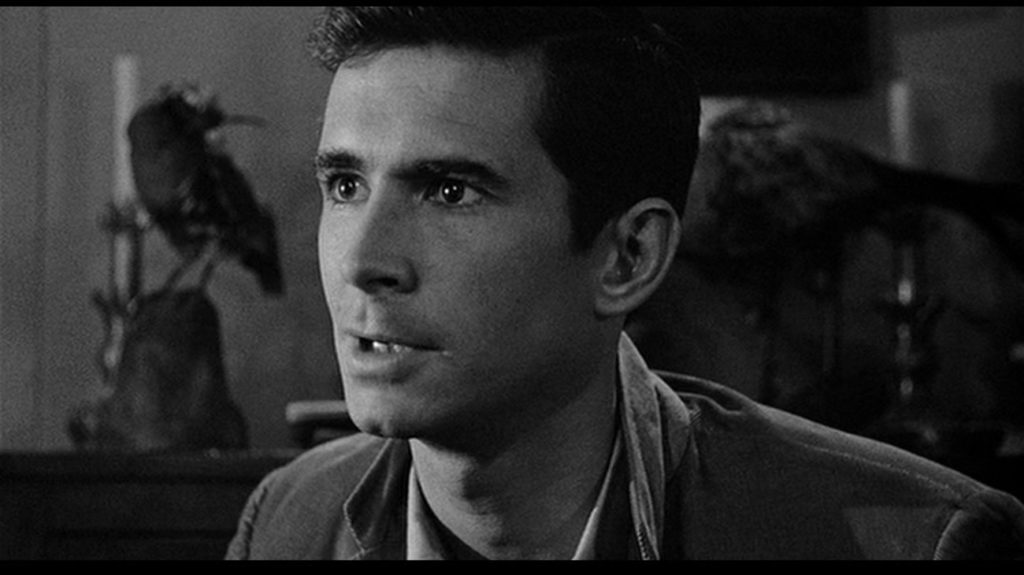

When the idea of “madhouses” comes up, Norman’s half of the conversation cuts to a close-up as well. His performance drastically changes here as he lets his mask down a little, and this close-up focuses on those changes. But this shot really emphasizes the neat little visual trick with the lighting that has been going on this whole time. With harsh lighting on only one half of his face, the character’s physical appearance is highlighted (and reveals also what a brilliant bit of casting Anthony Perkins was; not just for his acting skills). Norman, with his sharp nose and thin neck, has very bird like features and you can see the comparison with the stuffed creatures behind him. He is the predator feeling out his prey.

But Norman collects himself and explains away his behavior as his love for his mother, giving the great line “we all go a little mad sometimes.” This resonates with Marion who sees her own recent behavior as out of character. She stands up and the camera pans with her, but little does she know it is already too late for her.

Right behind her and out of her sight is the menacing dark figure of a raven, classically a symbol of death. Here it represents Norman, creeping up on his unsuspecting victim. Its sharp beak foreshadowing the killer’s knife.

Marion now leaves the office to go back to her room. Up until this point Marion has been our point-of-view character. But she walks out and the camera (and thus us as the audience) stays behind in Norman’s world. There are even those grandmotherly curtains in the right of the frame to remind us whose mental space we are still in.

The film cuts back to Norman in the doorway. He is framed in the middle of the shot to draw attention to his behavior front and center. The expression on his face is completely different now; now alone, his mask has been dropped. We can now see him truly as a killer. In the background we still see that evil raven, the lighting stretching its shadow up the wall. Ever so briefly the shadow halos Norman’s head making a symbolic connection between these two birds of prey. To drive home the correlation, Norman nibbles on some crumbs like a bird in the park. He walks forward and confirms Marion’s lies, giving a chilling look of contentment.

Norman closes the door and retreats into his own world of shadows. The camera pans with him until he gets to the far wall. For a split second we see maybe a moment on his face where he reconsiders what he is about to do. But framed right next to his head, almost as if it was whispering in his ear, is that sinister owl. It is the darkness, the “mother” half of his personality locked away in his mind, that talks him back into it. The performance with Norman’s face is spectacular as we see him, wordlessly, back out and then fully commit to his crime again.

In a final bit of foreshadowing, Norman turns to uncover a hidden hole in the wall which he uses to peep in on Marion undressing. Concealing it though is an oil painting of sexual violence which has been in plain view on the wall this whole time.

Norman leans in and the film cuts to a side shot close-up. Most of the shot is covered in darkness except for the light coming out of the hole which highlights Norman’s eye. This shows how we have now moved into Norman’s point of view and the rest of the scene before he leaves the room is exactly what Norman sees, Marion undressing and getting in the shower.

We can end here on one of the most famous and icon images from the film, coming right before the sequence that Psycho is most know for. A common idiom is”eyes are the windows to the soul” and we have taken a trip into Norman’s. Much of what defines a character is performance and dialogue and the sequence in the parlor has that in spades. But often overlooked is the amount of detail and care that is chosen in the visuals. We learn just as much about Norman from the shot selection as the script. The biggest theme running through Psycho is the madness hidden underneath the everyday personified in Norman’s character. This sequence is one of the best examples of this theme in the film and exemplifies why Psycho is not just a classic horror film but a masterpiece of cinema in general.