Hope is the thing with feathers

The third leg of Ulrich Seidl's Paradise trilogy, Paradise: Hope, isn't nearly as severe and bleak as Love and Faith, nor is at unmitigated in its cruelty as I, for one, fully expected it to be, given the setting of a "fat camp" for overweight teenagers to be humiliated, overworked, and deprived into slimming down (something that none of them actually seem to do). It is not, mind you, free of cruelty: there is a scene that finds all the campers lined in a row and forced to smack their guts and buttocks as they skinny adult trainer runs them cheerfully through the song "If You're Happy and You Know It, Clap Your Fat", a moment to pierce the heart of any of us who know weight problems in youth.

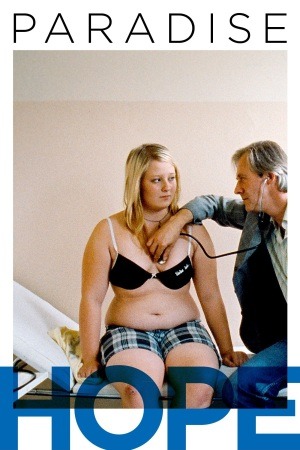

In the main, though, it's a surprisingly conventional story of a 13-year-old girl, Melanie (Melanie Lenz), who's shipped off to someplace she desperately wants to be while her aunt is busy spreading an especially dogmatic strain of Catholicism and her mother is off buying sex in Africa (events covered in the previous movies and not even slightly alluded to here, though the aunt puts in a cameo and the mother is unheard on the other side of a phone). In this powder-keg of hostile adolescence, Melanie makes unexpected friends, finds herself exploring sex in a safely proscribed net of boys and girls equally intrigued and terrified of each others' bodies, and finding a very cautious first love. Things start to get weird when the boy she loves turns on her after they start to get to serious, but it's all part of the great cycle of coming-of-age. Also, the boy is Arzt (Joseph Lorenz), the 50-something doctor watching out for all the kids' medical wellbeing. Ah, there's that special Austrian miserabilist flair we were waiting for.

Hope, thankfully, doesn't belabor the ghastliness of its scenario, or situate itself as a nightmare melodrama about a child being preyed upon by a pedophile (it's actually a bit unclear how far the relationship between the two progresses; certainly into the realm of "totally unacceptable", but probably well shy of anything overtly sexual). Limiting itself entirely to Melanie's perspective and awareness of events, it counts entirely on the viewer's understanding of everything that's wrong with the central relationship, and saves itself the Lifetime movie ominousness that would easily have scuttled the film if it had been there. Instead, by refusing to make a horror movie of it, Hope is both more naturalist and also more upsetting, since the non-monstrous Arzt is far harder to digest than a stock movie villain Arzt would have been. People who look and seem decent and in most ways are probably decent are still capable of coming this close to committing evil acts, and if Arzt ends up pulling back, it's not necessarily in a way that makes us think, "see, he was a good guy all along", for that's manifestly not true.

Still, it's a sign of how much less programmatic Hope is than the other two films that a man and girl can dance around the pedophilia line like this without it plunging either of them into moral chaos; or, for that matter, without it coming to define the movie. Hope is a far less ironic title than Love and less cynical than Faith - it is a movie about a girl being exposed to all kinds of messy, complicated, fascinating elements of life, and predatory doctors are only one of them. It's arguable that the most important relationship to the the narrative isn't between Melanie and Arzt at all, but between Melanie and Verena (Verana Lehbauer), another camper who acts as Melanie's spirit guide, of a fashion, showing her how to be alive and make terrible mistakes and come back out of them. The film is hopeful in that it is about the feeling of being a young teenager who gets to experience everything for the first time; that can be scary and dangerous, it can be boring and empty, and Hope doesn't deny that. But it's also rich and intoxicating, and Hope is very eager to foreground that, making this easily the most pleasant and palatable of the Paradise films.

It's probably not therefore the best - Love, with its much more complex and unconventional psychology, wins that title. The best parts of Hope do have a tendency to remind one of other movies which do about the same thing to about the same effect (if generally not in the same way - pedophile movies are thin on the ground, even in Europe), and though Melanie is a well-drawn character, she's not at all unique. Right alongside being the most pleasant in the trilogy, Hope is also the least demanding, with images that read themselves far more readily than anything in the first two, and more clear-cut situations with more generically-defined stakes.

Still, it's rewarding and humane in a way that Faith absolutely isn't and even if its imagery is less sophisticated than Love's, it still has some very striking compositions that take excellent use of the film's specific geometry (it takes place largely in rooms with lots of right angles and empty space, and Seidl and cinematographers Edward Lachman and Wolfgang Thaler exploit that for many fine images of children being lined up and penned by the adult characters and the frame alike). If it's not as probing and thus not as evocative, it's still successfully able to sketch out a specific emotional state as lived by a specific human being, and on that level, it's a success.

Also, as the shortest of the trilogy by 20+ minutes, it's also the only one that doesn't feel redundant and bloated and anxious to justify itself as a feature; it has feels self-contained as neither Love nor Faith do. If there's one thing we can all get behind, it's that self-contained movies that don't take more time to tell their stories than they need to are the way to go.

7/10

In the main, though, it's a surprisingly conventional story of a 13-year-old girl, Melanie (Melanie Lenz), who's shipped off to someplace she desperately wants to be while her aunt is busy spreading an especially dogmatic strain of Catholicism and her mother is off buying sex in Africa (events covered in the previous movies and not even slightly alluded to here, though the aunt puts in a cameo and the mother is unheard on the other side of a phone). In this powder-keg of hostile adolescence, Melanie makes unexpected friends, finds herself exploring sex in a safely proscribed net of boys and girls equally intrigued and terrified of each others' bodies, and finding a very cautious first love. Things start to get weird when the boy she loves turns on her after they start to get to serious, but it's all part of the great cycle of coming-of-age. Also, the boy is Arzt (Joseph Lorenz), the 50-something doctor watching out for all the kids' medical wellbeing. Ah, there's that special Austrian miserabilist flair we were waiting for.

Hope, thankfully, doesn't belabor the ghastliness of its scenario, or situate itself as a nightmare melodrama about a child being preyed upon by a pedophile (it's actually a bit unclear how far the relationship between the two progresses; certainly into the realm of "totally unacceptable", but probably well shy of anything overtly sexual). Limiting itself entirely to Melanie's perspective and awareness of events, it counts entirely on the viewer's understanding of everything that's wrong with the central relationship, and saves itself the Lifetime movie ominousness that would easily have scuttled the film if it had been there. Instead, by refusing to make a horror movie of it, Hope is both more naturalist and also more upsetting, since the non-monstrous Arzt is far harder to digest than a stock movie villain Arzt would have been. People who look and seem decent and in most ways are probably decent are still capable of coming this close to committing evil acts, and if Arzt ends up pulling back, it's not necessarily in a way that makes us think, "see, he was a good guy all along", for that's manifestly not true.

Still, it's a sign of how much less programmatic Hope is than the other two films that a man and girl can dance around the pedophilia line like this without it plunging either of them into moral chaos; or, for that matter, without it coming to define the movie. Hope is a far less ironic title than Love and less cynical than Faith - it is a movie about a girl being exposed to all kinds of messy, complicated, fascinating elements of life, and predatory doctors are only one of them. It's arguable that the most important relationship to the the narrative isn't between Melanie and Arzt at all, but between Melanie and Verena (Verana Lehbauer), another camper who acts as Melanie's spirit guide, of a fashion, showing her how to be alive and make terrible mistakes and come back out of them. The film is hopeful in that it is about the feeling of being a young teenager who gets to experience everything for the first time; that can be scary and dangerous, it can be boring and empty, and Hope doesn't deny that. But it's also rich and intoxicating, and Hope is very eager to foreground that, making this easily the most pleasant and palatable of the Paradise films.

It's probably not therefore the best - Love, with its much more complex and unconventional psychology, wins that title. The best parts of Hope do have a tendency to remind one of other movies which do about the same thing to about the same effect (if generally not in the same way - pedophile movies are thin on the ground, even in Europe), and though Melanie is a well-drawn character, she's not at all unique. Right alongside being the most pleasant in the trilogy, Hope is also the least demanding, with images that read themselves far more readily than anything in the first two, and more clear-cut situations with more generically-defined stakes.

Still, it's rewarding and humane in a way that Faith absolutely isn't and even if its imagery is less sophisticated than Love's, it still has some very striking compositions that take excellent use of the film's specific geometry (it takes place largely in rooms with lots of right angles and empty space, and Seidl and cinematographers Edward Lachman and Wolfgang Thaler exploit that for many fine images of children being lined up and penned by the adult characters and the frame alike). If it's not as probing and thus not as evocative, it's still successfully able to sketch out a specific emotional state as lived by a specific human being, and on that level, it's a success.

Also, as the shortest of the trilogy by 20+ minutes, it's also the only one that doesn't feel redundant and bloated and anxious to justify itself as a feature; it has feels self-contained as neither Love nor Faith do. If there's one thing we can all get behind, it's that self-contained movies that don't take more time to tell their stories than they need to are the way to go.

7/10