Tarr B_la is the man

Tarr Béla's penultimate film (barring an un-retirement), 2007's The Man from London, is among those movies for which more time is needed: at this writing, nearly seven full years have passed since it prickly, divisive premiere at the Cannes International Film Festival, but that event still hovers over the movie, working in tandem with some of the particular eccentricities of its production to over up, if only as a ghost, the suspicion that it's not a "real" Tarr film. Certainly, if we look at the evolution of movies from Almanac of Fall in 1985 to The Turin Horse in 2011, there is a visceral development across them, from the brink of apocalypse through to apocalypse to the post-apocalypse, and The Man from London does not really belong in this same sweep; it especially does not feel like the next film in a row after Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies, which do very much feel like one another in some key ways. (I am driven to wonder if Tarr's retirement announcement, made prior to The Turin Horse, was in response to The Man from London's conflicted reception: if he resented, on some level, the sense that he'd only be respected as long as he kept making Tarr Béla films, unable to ever evolve or explore. And well he might resent that).

Everything else, though, is parochialism - Tarr and his producers even vocally wondered if the brittle Cannes reception might have been the fault of an audio dub that wasn't quite ready yet. Even in the final version, there's something distracting about seeing French and English words coming out of mouths not speaking French or English; of seeing and hearing art film darling Tilda Swinton using her own voice in French while her lips move in English. But every Tarr film had been dubbed, and several of them had employed actors just as famous in Hungary as Swinton is in the anglosphere. So to use those as reasons to make The Man from London some kind of deficient "other" in the director's career (and I have seen people do this, though thankfully not many) is no kind of intellectual position at all.

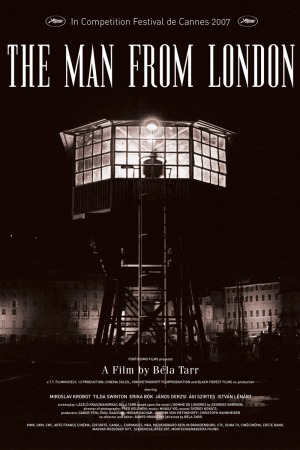

And to the last substantive criticism of the film that I've encountered, that it's too much of a "genre story" for Tarr's style - well, that's the fun of it, really. We have here an adaptation of a1934 Belgian crime novel by Georges Simenon, done in an aesthetic that suggests equal parts American film noir from the '50s and German Expressionism from the '20s, both of them filtered through the marathon-length takes and portentous camera movements of Tarr's mature career. He, co-director Hranitzky Ágnes, and cinematographer Fred Kelemen assembled here some potent and emphatically weird visuals that call attention to just how much lingering realism was still hanging onto something like Werckmeister Harmonies: the intensely harsh black-and-white compositions that dominate The Man from London leave its setting, a railyard next to the docks in an unspecified French-speaking city, with the texture of a nightmare or hallucination of a real place where all the proportions and lines are out of order.

The plot, which is baiting the audience as much as doing anything else, is not unlike fellow Cannes '07 competitor No Country for Old Men: one inky black night, a workaday nobody named Maloin (Miroslav Krobot) spots a pair of men having a fight at the edge of the dock beneath his observation room overlooking the railway. One man and his briefcase end up in the dark water as a result of this fight; Maloin wanders down after the survivor has fled, retrieving the briefcase, and finding it stuffed to the brim with British pounds. Telling no-one what he found, he goes about the daily routine of his life, only with a new patina of insanity that confuses and to some degree terrifies his wife, Camélia (Swinton), and their daughter, Henriette (Bók Erika). In the meantime, a man from London, Inspector Morrison (Lénárt István) shows up in town to inquire about the theft of £55,000 from a theater owner named Mitchell, a crime that the victim is content to blame on a former associate named Brown (Derzsi János), who has been slinking around in places that lead us to believe he's probably guilty; only he can't take up Mitchell's surprisingly generous offer to forgive all if the money is returned, what with Maloin having taken the money and all.

All of which sounds like a thing, and it's not the thing that The Man from London is, at all. What it is, really, is a film about observing things from the outside: the film is absolutely rotten with drastically canted angles and scenes that emphasise Maloin watching or listening to things that he has no connection to, and a certain point, the film gets in on the act, making us spectators to a story that hasn't been sufficiently contextualised. The thrilling climax of whatever crime story is going on here takes place as we stare at a closed door for at least a couple of minutes, hearing nothing but the drone of the wind; the biggest emotional impact of anything in the movie is a shot of Brown's wife (Szirtes Ági) looking distressed, an image we see twice, without learning anything else about her; in fact, unless my memory is completely off, these two long takes are literally the only times we get to spend any time with her. We see and process her emotions, but they are taking place entirely within her, unable to reach us.

It is a film, then, about disconnection: about being aware that there are people living lives and having feelings and committing crimes and dying, and being even more aware that all this has nothing to do with you at all. Perhaps the suffocating noir visuals of the docks and railyard are meant to express precisely that: not just other people, but the entire world acting in a hostile, alien, unknowable way. The film's opening shot is an exhaustively long (12 minutes!), glacially slow tracking shot up and across the prow of a ship, focused so intently on the surface of the thing that it's actual meaning and shape get lost, and this is the most stable, unexotic object imaginable in this film's world. The idea, as I take it, is that the longer and closer you focus on something, the more unreal and unrecognisable it becomes, like saying a word over and over until it becomes gibberish.

All this results in a film more icy and alien than anything else Tarr and his collaborators (the usual suspects: Vig Mihály compsed the score, Krasznahorkai László co-wrote the script with Tarr, Hranitzky edited and contributed to the production design), a deliberate anti-narrative about deliberate anti-characters, with only poor Camélia coming across as someone with any inner life at all, and then only because Maloin is so profoundly unable to comprehend it. Combined with the generally static energy of the protagonist, the film is perhaps the most uncomfortable thing to watch in the director's largely unfriendly career; and this, also, maybe contributed to its mixed reception out of the gate. It presents a horrifyingly arbitrary world where every choice by every character is apparently a disastrous one, but they're all so modulated, all so clearly happening to someone else, that it's hard to feel much moved by them. This, then, is the film's horror: it reflects a world of alienation so complete that even we in the audience can't see past it. It's a hard and cruel film, the moral universe of classic noir taken to its absolute extreme, and a gripping experience for anybody already onboard Tarr's wavelength, though I think it would be an especially grueling first exposure.

Everything else, though, is parochialism - Tarr and his producers even vocally wondered if the brittle Cannes reception might have been the fault of an audio dub that wasn't quite ready yet. Even in the final version, there's something distracting about seeing French and English words coming out of mouths not speaking French or English; of seeing and hearing art film darling Tilda Swinton using her own voice in French while her lips move in English. But every Tarr film had been dubbed, and several of them had employed actors just as famous in Hungary as Swinton is in the anglosphere. So to use those as reasons to make The Man from London some kind of deficient "other" in the director's career (and I have seen people do this, though thankfully not many) is no kind of intellectual position at all.

And to the last substantive criticism of the film that I've encountered, that it's too much of a "genre story" for Tarr's style - well, that's the fun of it, really. We have here an adaptation of a1934 Belgian crime novel by Georges Simenon, done in an aesthetic that suggests equal parts American film noir from the '50s and German Expressionism from the '20s, both of them filtered through the marathon-length takes and portentous camera movements of Tarr's mature career. He, co-director Hranitzky Ágnes, and cinematographer Fred Kelemen assembled here some potent and emphatically weird visuals that call attention to just how much lingering realism was still hanging onto something like Werckmeister Harmonies: the intensely harsh black-and-white compositions that dominate The Man from London leave its setting, a railyard next to the docks in an unspecified French-speaking city, with the texture of a nightmare or hallucination of a real place where all the proportions and lines are out of order.

The plot, which is baiting the audience as much as doing anything else, is not unlike fellow Cannes '07 competitor No Country for Old Men: one inky black night, a workaday nobody named Maloin (Miroslav Krobot) spots a pair of men having a fight at the edge of the dock beneath his observation room overlooking the railway. One man and his briefcase end up in the dark water as a result of this fight; Maloin wanders down after the survivor has fled, retrieving the briefcase, and finding it stuffed to the brim with British pounds. Telling no-one what he found, he goes about the daily routine of his life, only with a new patina of insanity that confuses and to some degree terrifies his wife, Camélia (Swinton), and their daughter, Henriette (Bók Erika). In the meantime, a man from London, Inspector Morrison (Lénárt István) shows up in town to inquire about the theft of £55,000 from a theater owner named Mitchell, a crime that the victim is content to blame on a former associate named Brown (Derzsi János), who has been slinking around in places that lead us to believe he's probably guilty; only he can't take up Mitchell's surprisingly generous offer to forgive all if the money is returned, what with Maloin having taken the money and all.

All of which sounds like a thing, and it's not the thing that The Man from London is, at all. What it is, really, is a film about observing things from the outside: the film is absolutely rotten with drastically canted angles and scenes that emphasise Maloin watching or listening to things that he has no connection to, and a certain point, the film gets in on the act, making us spectators to a story that hasn't been sufficiently contextualised. The thrilling climax of whatever crime story is going on here takes place as we stare at a closed door for at least a couple of minutes, hearing nothing but the drone of the wind; the biggest emotional impact of anything in the movie is a shot of Brown's wife (Szirtes Ági) looking distressed, an image we see twice, without learning anything else about her; in fact, unless my memory is completely off, these two long takes are literally the only times we get to spend any time with her. We see and process her emotions, but they are taking place entirely within her, unable to reach us.

It is a film, then, about disconnection: about being aware that there are people living lives and having feelings and committing crimes and dying, and being even more aware that all this has nothing to do with you at all. Perhaps the suffocating noir visuals of the docks and railyard are meant to express precisely that: not just other people, but the entire world acting in a hostile, alien, unknowable way. The film's opening shot is an exhaustively long (12 minutes!), glacially slow tracking shot up and across the prow of a ship, focused so intently on the surface of the thing that it's actual meaning and shape get lost, and this is the most stable, unexotic object imaginable in this film's world. The idea, as I take it, is that the longer and closer you focus on something, the more unreal and unrecognisable it becomes, like saying a word over and over until it becomes gibberish.

All this results in a film more icy and alien than anything else Tarr and his collaborators (the usual suspects: Vig Mihály compsed the score, Krasznahorkai László co-wrote the script with Tarr, Hranitzky edited and contributed to the production design), a deliberate anti-narrative about deliberate anti-characters, with only poor Camélia coming across as someone with any inner life at all, and then only because Maloin is so profoundly unable to comprehend it. Combined with the generally static energy of the protagonist, the film is perhaps the most uncomfortable thing to watch in the director's largely unfriendly career; and this, also, maybe contributed to its mixed reception out of the gate. It presents a horrifyingly arbitrary world where every choice by every character is apparently a disastrous one, but they're all so modulated, all so clearly happening to someone else, that it's hard to feel much moved by them. This, then, is the film's horror: it reflects a world of alienation so complete that even we in the audience can't see past it. It's a hard and cruel film, the moral universe of classic noir taken to its absolute extreme, and a gripping experience for anybody already onboard Tarr's wavelength, though I think it would be an especially grueling first exposure.