Hollywood Century, 1931: In which we praise Marxist anarchy

The five films made by the four Marx brothers at Paramount between 1929 and 1933 are the stuff of legend, and the basis for what is likely the most famous career of any comic team in history (and this despite the first of those films, The Cocoanuts, sagging under the weight of an insipid romantic B-plot involving none of the brothers). Two more near-masterpieces followed at MGM, but the version of the comics presented by that studio was tame and domesticated compared to the very real sense of anything-goes danger presented in a quartet of movies with titles referencing animals; a probably not accidental nod to the tendency of these films to feel like somebody opened all the cages at the zoo.

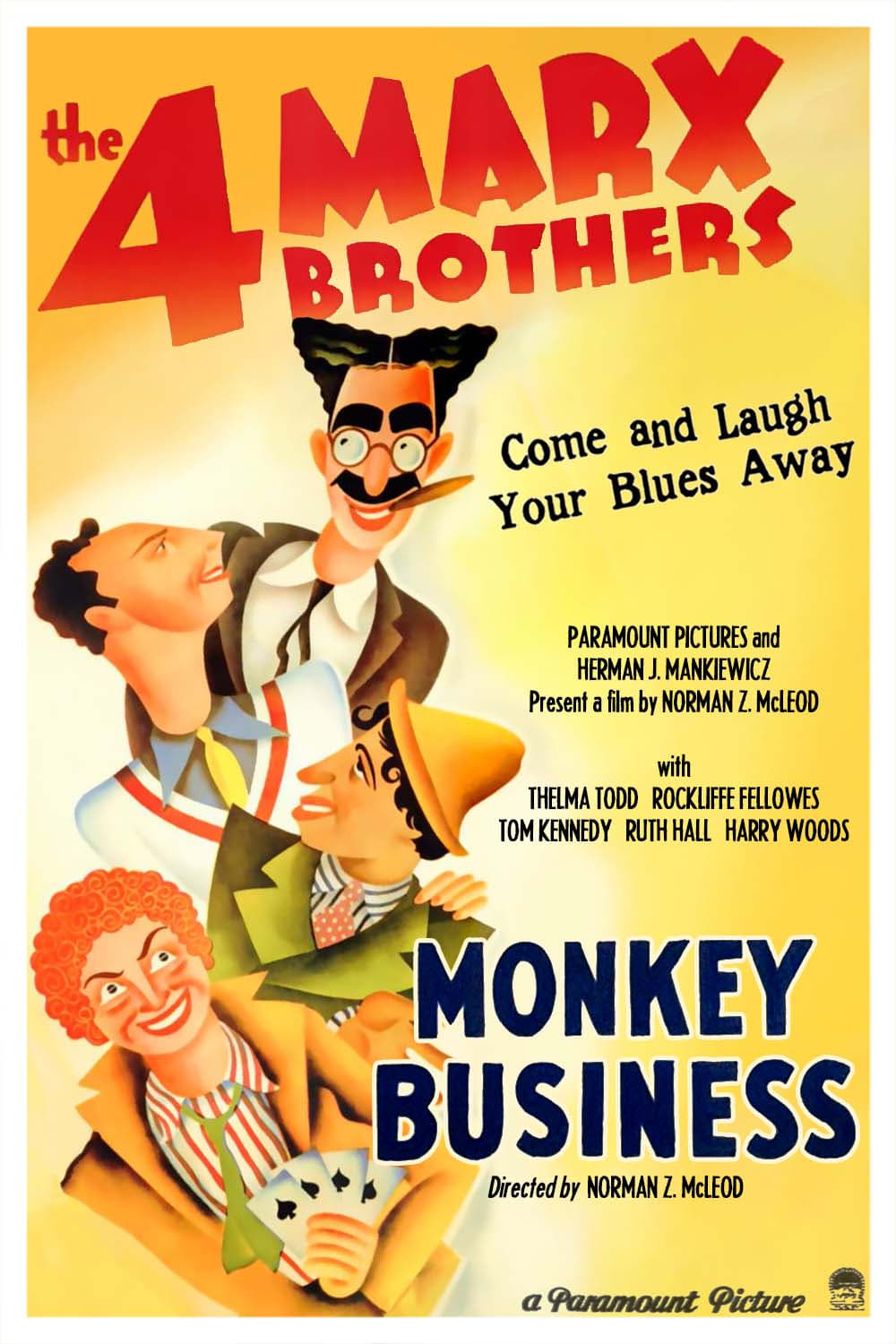

Of these, perhaps the most significant, while also perhaps the least successful, is 1931's Monkey Business. The latter point is harder to quantify, but as concerns the former, the basic facts are that it was the first Marx brothers film shot on the West Coast, after The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers were filmed at the Kaufman Astoria Studios in New York (the Marxes being, at this time, Broadway stars looking to make the jump to movies like so many other theater icons at the dawn of the sound era); it was also the first of their movies made from an entirely new script by S.J. Perelman and Will B. Johnstone, instead of being adapted from one of their stage shows. In this film, the brothers don't play characters - of course, they never really played characters, but simply versions of their well-honed personae tagged with different names to suit different scenarios; this was even true of their debut, when most moviegoers throughout the United States and the rest of the world likely didn't have a good sense of who they were. But even so, Monkey Business is the film where the fig leaf was taken away: in addition to having no names spoken on screen (the end credits simply call them by their respective stage names), they have no apparent history, just four guys who clearly know each other well ending up in a bunch of comic situations and responding to them. Outside of the fact that they start off penniless, there are no tweaks that would have to be made for this exact story to work if it revolved around the literal Marx brothers, superstar vaudevillians who elected to stow away onboard a transatlantic ship. It is their hang-out movie, so to speak.

Owing to all of this, maybe, Monkey Business also strikes me as being the purest Marx brothers film, the one that exemplifies what I have always regarded as their chief characteristic: a willfulness about flaunting decency and openly mocking the Nice People. It's the easiest, laziest thing in the world to talk about the meta-narratives American films from the '30s tell about the Great Depression, but let's do it anyway: there's something about watching four people (or three, in the MGM films) surrounded by costly trappings and rich people, and treating them with a complete absence of respect or dignity, that feels like it could never attain such a nervy charge at any other point in American history, until maybe the 2010s. And nobody is making films like this in the 2010s.

But to focus in a little bit more on what I was saying: Monkey Business, almost entirely divorced from a plot, functions mostly as an assembly line of gags and sketches, all clustered into one of two large chunks. The first part of the movie follows the brothers - or whatever relationship we want to imagine for them - on a ship, with Groucho (for the uninitiated: the mustache-and-glasses-wearing sarcastic one with a penchant for sexual innuendo - and as this film itself teaches us, love flies out the door when money comes innuendo) and Zeppo (the straight man, though he was perhaps the most versatile and talented as a performer) ending up helping one gangster Alky Briggs (Harry Woods), while Chico (the dim-witted fake Italian) and Harpo (the silent one who's more dementedly anarchic than the others combined) end up helping Briggs's rival, Big Joe Helton (Rockliffe Fellows). Groucho, meanwhile, flirts shamelessly with Briggs's resentful wife Lucille (Thelma Todd), while Zeppo falls in love with Helton's innocent daughter Mary (Ruth Hall). And while all of that happens, with no real attention to coherence or causality, the four race around the ship, one step ahead of the furious crew, causing all sorts of nonsensical mischief.

The second part finds them doing much the same at a fancy society costume party that Helton throws, and from which Briggs kidnaps Mary, ending in a chase that resolves in a fight in a barn. And if Monkey Business has one serious handicap that holds it back from the masterpiece-level status of the later Horse Feathers and Duck Soup, it's that the film takes a massive step down in madness and comic inspiration when it leaves the ship. The film is still funny, sure; the lines still zing, the physical comedy remains astonishingly fluid and clever (even in their lowest moments, Groucho was still one of the great joke-deliverers in cinema, and Harpo the most perfect physical comedian of the sound era). But the opening sequence - which makes up more than half of the 77-minute movie, so it's not like we're talking about some dreadful wasteland of hours at the end of the film - has so much more potency to it! It is, both in the Marx brothers' filmography and in '30s Hollywood generally, unmatched in its unhinged lunacy. Freed from all but the the most rudimentary plot and character relationships, the comedians are free to indulge in whatever acts of wild comedy they like; the result is a non-stop flow of gags that have a legitimate feeling of radicalism like very little else. Nothing is stable in Monkey Business: every conversation feels like it could go in any direction, with even the non-Marx characters eventually folded into the mirror-world logic that, in other movies, would cause them to at least question the sanity of the events unfolding around them.

As a work of cinema, Monkey Business doesn't do much besides record action, occasionally using close-ups for effect, and cutting to silently hide set-ups; by and large, the Marx brothers didn't end up in films that were particularly inventive; Norman Z. McLeod, working with them for the first of two films, doesn't do much else besides make sure they're in frame. And this is perhaps another reason that the film doesn't quite land with as much punch as Duck Soup - the only conspicuously well-made film of their career - for the jokes are not packaged in a way that makes them work well. Though there is a lengthy sequence centered on Maurice Chevalier impressions - my favorite part of the movie, incidentally - that could only work as well as it does, and in the specific way it does, in the context of early sound cinema, and as such doesn't have as much of the "we're recording a stage performance!" energy that mutes certain passages of Animal Crackers (also, compared to that film, Monkey Business doesn't have the same ragged editing that comes from censorship and trying to badly stitch together improv).

Still, comedy is a genre unique in its ability to succeed even if the filmmaking is flaccid - there is probably a better version of Monkey Business with a more gifted and versatile director at the helm, but the Monkey Business we have is still mostly brilliant, with the inventiveness and flawless execution of the comedy routines doing all the work of making it great. It's not the most dynamic and timeless of the brothers' movies (the fact that it boasts a lengthy Maurice Chevalier joke already tells us that it can't help but be dated), but it has enough moments and lines to stand alongside any of them as an essential holy text of American comedy.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1931

-Universal's Dracula and Frankenstein establish the horror genre in its pure form in America

-Charles Chaplin makes his final true silent film and his masterpiece, City Lights

-The success of Little Caesar and The Public Enemy at Warner Bros. causes the popularity of the gangster movie to explode

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1931

-Fritz Lang's M in Germany and René Clair's Le million in France revolutionise the use of sound in film in two wildly different directions

-Mário Peixoto's highly experimental Limite is the first Brazilian film to make a major impact internationally

-Talkies comes to India, led by the now-lost Alam Ara

Of these, perhaps the most significant, while also perhaps the least successful, is 1931's Monkey Business. The latter point is harder to quantify, but as concerns the former, the basic facts are that it was the first Marx brothers film shot on the West Coast, after The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers were filmed at the Kaufman Astoria Studios in New York (the Marxes being, at this time, Broadway stars looking to make the jump to movies like so many other theater icons at the dawn of the sound era); it was also the first of their movies made from an entirely new script by S.J. Perelman and Will B. Johnstone, instead of being adapted from one of their stage shows. In this film, the brothers don't play characters - of course, they never really played characters, but simply versions of their well-honed personae tagged with different names to suit different scenarios; this was even true of their debut, when most moviegoers throughout the United States and the rest of the world likely didn't have a good sense of who they were. But even so, Monkey Business is the film where the fig leaf was taken away: in addition to having no names spoken on screen (the end credits simply call them by their respective stage names), they have no apparent history, just four guys who clearly know each other well ending up in a bunch of comic situations and responding to them. Outside of the fact that they start off penniless, there are no tweaks that would have to be made for this exact story to work if it revolved around the literal Marx brothers, superstar vaudevillians who elected to stow away onboard a transatlantic ship. It is their hang-out movie, so to speak.

Owing to all of this, maybe, Monkey Business also strikes me as being the purest Marx brothers film, the one that exemplifies what I have always regarded as their chief characteristic: a willfulness about flaunting decency and openly mocking the Nice People. It's the easiest, laziest thing in the world to talk about the meta-narratives American films from the '30s tell about the Great Depression, but let's do it anyway: there's something about watching four people (or three, in the MGM films) surrounded by costly trappings and rich people, and treating them with a complete absence of respect or dignity, that feels like it could never attain such a nervy charge at any other point in American history, until maybe the 2010s. And nobody is making films like this in the 2010s.

But to focus in a little bit more on what I was saying: Monkey Business, almost entirely divorced from a plot, functions mostly as an assembly line of gags and sketches, all clustered into one of two large chunks. The first part of the movie follows the brothers - or whatever relationship we want to imagine for them - on a ship, with Groucho (for the uninitiated: the mustache-and-glasses-wearing sarcastic one with a penchant for sexual innuendo - and as this film itself teaches us, love flies out the door when money comes innuendo) and Zeppo (the straight man, though he was perhaps the most versatile and talented as a performer) ending up helping one gangster Alky Briggs (Harry Woods), while Chico (the dim-witted fake Italian) and Harpo (the silent one who's more dementedly anarchic than the others combined) end up helping Briggs's rival, Big Joe Helton (Rockliffe Fellows). Groucho, meanwhile, flirts shamelessly with Briggs's resentful wife Lucille (Thelma Todd), while Zeppo falls in love with Helton's innocent daughter Mary (Ruth Hall). And while all of that happens, with no real attention to coherence or causality, the four race around the ship, one step ahead of the furious crew, causing all sorts of nonsensical mischief.

The second part finds them doing much the same at a fancy society costume party that Helton throws, and from which Briggs kidnaps Mary, ending in a chase that resolves in a fight in a barn. And if Monkey Business has one serious handicap that holds it back from the masterpiece-level status of the later Horse Feathers and Duck Soup, it's that the film takes a massive step down in madness and comic inspiration when it leaves the ship. The film is still funny, sure; the lines still zing, the physical comedy remains astonishingly fluid and clever (even in their lowest moments, Groucho was still one of the great joke-deliverers in cinema, and Harpo the most perfect physical comedian of the sound era). But the opening sequence - which makes up more than half of the 77-minute movie, so it's not like we're talking about some dreadful wasteland of hours at the end of the film - has so much more potency to it! It is, both in the Marx brothers' filmography and in '30s Hollywood generally, unmatched in its unhinged lunacy. Freed from all but the the most rudimentary plot and character relationships, the comedians are free to indulge in whatever acts of wild comedy they like; the result is a non-stop flow of gags that have a legitimate feeling of radicalism like very little else. Nothing is stable in Monkey Business: every conversation feels like it could go in any direction, with even the non-Marx characters eventually folded into the mirror-world logic that, in other movies, would cause them to at least question the sanity of the events unfolding around them.

As a work of cinema, Monkey Business doesn't do much besides record action, occasionally using close-ups for effect, and cutting to silently hide set-ups; by and large, the Marx brothers didn't end up in films that were particularly inventive; Norman Z. McLeod, working with them for the first of two films, doesn't do much else besides make sure they're in frame. And this is perhaps another reason that the film doesn't quite land with as much punch as Duck Soup - the only conspicuously well-made film of their career - for the jokes are not packaged in a way that makes them work well. Though there is a lengthy sequence centered on Maurice Chevalier impressions - my favorite part of the movie, incidentally - that could only work as well as it does, and in the specific way it does, in the context of early sound cinema, and as such doesn't have as much of the "we're recording a stage performance!" energy that mutes certain passages of Animal Crackers (also, compared to that film, Monkey Business doesn't have the same ragged editing that comes from censorship and trying to badly stitch together improv).

Still, comedy is a genre unique in its ability to succeed even if the filmmaking is flaccid - there is probably a better version of Monkey Business with a more gifted and versatile director at the helm, but the Monkey Business we have is still mostly brilliant, with the inventiveness and flawless execution of the comedy routines doing all the work of making it great. It's not the most dynamic and timeless of the brothers' movies (the fact that it boasts a lengthy Maurice Chevalier joke already tells us that it can't help but be dated), but it has enough moments and lines to stand alongside any of them as an essential holy text of American comedy.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1931

-Universal's Dracula and Frankenstein establish the horror genre in its pure form in America

-Charles Chaplin makes his final true silent film and his masterpiece, City Lights

-The success of Little Caesar and The Public Enemy at Warner Bros. causes the popularity of the gangster movie to explode

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1931

-Fritz Lang's M in Germany and René Clair's Le million in France revolutionise the use of sound in film in two wildly different directions

-Mário Peixoto's highly experimental Limite is the first Brazilian film to make a major impact internationally

-Talkies comes to India, led by the now-lost Alam Ara