Hollywood Century, 1937: In which budgets are exploded in the name of spectacle; and we learn an important lesson about film preservation

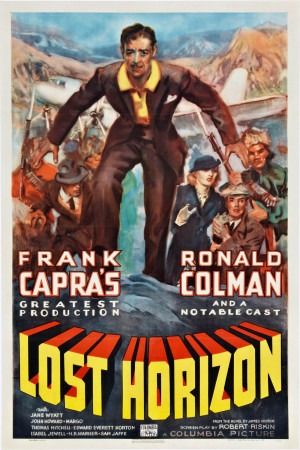

There's nothing easier than losing favor with Hollywood: no matter how successful a director's high peaks might be, all it takes is one project that ends up costing far too much and makes far too little back at the box office to tarnish even the brightest shining star. This truism takes us to one Frank Capra, who was the closest thing Hollywood in the '30s had to a brand-name filmmaker, and whose highly profitable run of movies with Columbia Pictures - one of the mini-majors, along with Universal and United Artists, but still responsible fora fair number of big hits - came to a bitter close over the matter of 1937's Lost Horizon, an epic that was green-lit with (by some accounts) the highest budget ever allocated to a Hollywood production, and still managed to shoot over it by a third. The film was cut from an assembly edit of six hours down to three and a half, down to two and a quarter, and finally down to 107, the length that was generally released in America to thoroughly unimpressive box office numbers. Capra and Columbia boss Harry Cohn fought nastily over the final cut, over pay, over contracts. And then the next year, Capra directed the Best Picture Oscar winner You Can't Take It with You, Columbia's biggest film of 1938, and it was like nothing ever happened. Because it's almost as easy to gain Hollywood's favor as it is to lose it. It's always, and only, about money.

Adapted by Capra's regular screenwriter Robert Riskin - they too had a falling-out, and didn't patch things up, either - from James Hilton's 1933 novel, the film tells of what happens when a planeful of Brits flees Shanghai following political upheavals in 1935. Cool-headed diplomat Robert Conway (Ronald Colman) is the head of the rescue mission, but it's really an Asian pilot (Val Duran) who dictates what's going to happen: the plane is crashed, deliberately, in the Himalayas, where the survivor (not including the hijacker) are found in the bitter snow by a team from a valley hidden deep in the mountains. This unbelievably idyllic place goes by the name of Shangri-La; a rural community guided, but not precisely "led" by the High Lama (Sam Jaffe) who dwells in the lamasery on a cliff overlooking the valley. He doesn't have much to do with everyday life, though; his primary actor is a certain Chang (H.B. Warner), and it is this Chang who explains the ins and outs of life to the survivors, including Robert and his brother George (John Howard), con-man Henry Barnard (Thomas Mitchell), paleontologist Alexander Lovett (Edward Everett Horton), and Gloria Stone (Isabel Jewell), sixth months past her due date for dying of some dread disease. At first, only Robert is terribly excited by the calm sensibility that permeates Shangri-La; he is encouraged in this upon meeting the lovely Sondra (Jane Wyatt), an oddly European-looking resident of the valley. But as the rest find, one by one, that the slow pace and simple needs of life in the valley can be more rewarding than the chaos of the West - and that the valley has some unexplained power that can restore health and prolong life to extraordinary lengths - only George ends up staying angrily insistent that, goddammit, they need to get out of this weird Oriental hell.

So let's knock the unpleasant bit out of the way first. Lost Horizon has a racial politic that almost can't help but make a modern viewer feel a bit queasy - just the yellowface is enough for that, really, but the story grips with particular enthusiasm an idea of hyper-spiritual, Zen-like Asian spirituality that is, at any rate, a lot easier to handle than the notion of ignorant savage hordes of slant-eyed monsters in the Fu Manchu mode. Still, it is by all of the standards of our time - less so by the standards of its own (in fact, the film was later re-edited to downplay its over sympathy for the Chinese, when this became a political liability) - a deprecatory representation that's long on exoticising foreign culture. And this is not true only of the script: there are many shots that find Capra and cinematographer Joseph Walker framing characters and the Stephen Goosson-designed Shangri-La itself with a kind of precious fussiness, one that, on hand, stresses the ethereal nature of the place (which I think to be appropriate and good), and on the other, is deeply invested in making some kind of Orientalist art object of the frame that denies any kind of life or flexibility to the content.

All that being said, this is a fable, not an social documentary, and a certain sense of rich mystery and formalised ritual in the story and the visuals suits the material just fine. After all, the explicit, top-level narrative of Lost Horizon involves a man - a very British man (Colman could play no other kind), that is to say a man who embodies all the things that the phrase "white European colonialist" calls to mind - being thrown into a completely foreign environment and finding that he is entirely the better for it, and that it is a deeply spiritual place to be. The specific trappings do, of course, put Lost Horizon squarely in a tradition of Exotic Other stories, but I am now thinking less of the degree to which, nearly 80 years after its creation, the film matches contemporary tastes, but of how well it functions as a drama driven by its visuals; and I am inclined to say, it does this very well indeed.

One of the things I perpetually re-learn, as I get older and less worked over what films have political and social agendas I agree with, is that Capra - a filmmaker whose politics are very infrequently cotangent with my own - was a talented motherfucker. For all that he's tarred and feathered with the seemingly immortal slur of "Capra-corn", and accused of ticky-tacky sentiment, that criticism only works if you haven't actually seen many Capra films, especially since his most famous work - It's a Wonderful Life, though I wonder how much longer till Mr. Smith Goes to Washington eclipses it - actively repudiates that line of thinking, though many people do not realise this. Not that Lost Horizon is some kind of dour, cynical downer, but it does pretty bluntly suggest that all of "civilisation" - a word that the film unmistakably puts in those exact ironic quotes - is savagery, violence, and base behavior, and what we should hope for is not that some genius will come to save us from ourselves, but that there's a wonderful land far off in the untouchable mountains where a cluster of decent humanity can be saved and groomed until the world is ready for it. The movie says that we all long for a Shangri-La of our own; in so doing, it implies that damn few of us ever get one.

But that has nothing to do with Capra's quality as a filmmaker, of course. What I was starting to say just then was that he's actually quite a gifted craftsman of stirring, interesting visuals, and an extraordinary director of actors - the list of performers who gave their best or near-best performances under his guidance is not a short one, and this film certainly adds Ronald Colman to that list. I have little use for him on the whole: there's a packaged dignity to most of his acting that I find largely indigestible. But his slowly percolating enthusiasm is communicated here with subtlety and restraint, as Capra builds Robert Conway's character through simply watching Colman's feelings move quietly up through his face. And the last act, in which Conway is full of regret, dismay, and fear at the thought of losing his Shangri-La, is simply the best stuff in Colman's career, bleak without being punishing and hopeless.

The other thing that's really extraordinary about the way the film is put together is its use of sound: Dimitri Tiomkin's music especially, but sound effects too. There is a simple, almost primitive scheme used here: when things are chaotic, driven by conflict, or full of negative emotion, the film is loud. When things are serene, thoughtful, reflective, and at peace, the film is quiet. The opening is a violent rebellion, and then the sound drops out to almost nothing but dialogue on the plane. The plane crash is busy and metallic, and then the early scenes in Shangri-La lack even the hint of ambient noise or music. It's elementally powerful, working on an almost wholly subconscious front - and yet, if it's so obvious and simple, why does it feel so unusual? That the film includes virtually nothing on the soundtrack at its most peaceful moments, besides human voices - no birds, no chimes, no wind in the grass - is genuinely startling, but by God, does it work.

Clever filmmaking, and impressively grand filmmaking too: for a hell of an expensive film, Lost Horizon looks it, with massive sets and setpieces, presented by the filmmakers with an eye towards emphasising their scale - the film looks like it takes place in a huge valley surrounded by massive mountains. The use of stock footage from documentaries about the Himalayas certainly aids in this illusion, but it's not the only reason: the mountain sets often seem just as vast, and it should be noted, not without regret, that the studio-shoot footage and the stock footage don't cut together so cleanly, so consistently, that there's much of an illusion to be had, anyway. But setting that aside, it's a sprawling, epic-sized film, and however much Columbia hurt for it, this was money well spent.

And now, a complete change of subject for our final word. As noted, Lost Horizon was generally released at 107 minutes, with 132 minutes being the longest cut that was ever screened for a paying audience. In the '70s and '80s, a massive restoration was attempted, using every scrap of footage that could be scrounged up anywhere in the world. Though a complete soundtrack for the 132-minute cut was found, several minutes of visual information could not, and so the film ends up with several scenes playing out over stills. Meanwhile, the quality of the restored footage is immensely variable, with some of it so blurred and scratched that only context clues make it entirely clear what's going on. To a degree, then, watching the "full" version of Lost Horizon is an act of interpretation: you can gather what's going on and suppose what it might have looked like, but it requires work to get there. And this is not entirely unknown - the reconstructed A Star Is Born from 1954 is exactly the same kind of hybrid.

What is kind of delightful, or at least instructive is seeing the footage that was snipped out, the footage that Cohn deemed inessential. This includes, mind you, the scene where Lama explains his vision of peace and harmony, and clarifies the entire backstory of Shangri-La. So much for an idea-driven movie (it also includes a scene - one of the still photo reconstructions - where the film-long homoeroticism between Henry Barnard and Alexander Lovett sounds to have exploded into full-blown homosexual domesticity. Since this could hardly have been possible in a film made in America in 1937, even one with Edward Everett Horton, the missing visuals must have downplayed things fiercely). Undoubtedly, this moved faster, but that's really the only thing that can be said on its behalf. The longer version of the film is actually a film, with a throughline and clear character moments; yet it is also a compromised Frankenstein monster of passable and unacceptable elements. And so it is with film preservation and restoration: always a situation of coming as close as possible, never actually getting all the way there. Some things, like Shangri-La itself, are hidden away where no one will ever be able to see them again.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1937

-The first cel-animated feature film in history, Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premieres at the end of the year, going on to explode box office records

-Leo McCarey's devastating autumn-years romantic drama Make Way for Tomorrow opens, breaks everybody's heart who sees it

-Daffy Duck makes his first appearance in the Warner Bros. Looney Tune short Porky's Duck Hunt

Elsewhere in World cinema in 1937

-Jean Renoir's magnificent anti-war film Grand Illusion opens in France

-Little-known in the West Yamanaka Sadao's Humanity and Paper Balloons makes a profound impact on the future development of Japanese period dramas, or jidaigeki

-The Polish production The Dybbuk is one of the earliest important works of Yiddish-language filmmaking

Adapted by Capra's regular screenwriter Robert Riskin - they too had a falling-out, and didn't patch things up, either - from James Hilton's 1933 novel, the film tells of what happens when a planeful of Brits flees Shanghai following political upheavals in 1935. Cool-headed diplomat Robert Conway (Ronald Colman) is the head of the rescue mission, but it's really an Asian pilot (Val Duran) who dictates what's going to happen: the plane is crashed, deliberately, in the Himalayas, where the survivor (not including the hijacker) are found in the bitter snow by a team from a valley hidden deep in the mountains. This unbelievably idyllic place goes by the name of Shangri-La; a rural community guided, but not precisely "led" by the High Lama (Sam Jaffe) who dwells in the lamasery on a cliff overlooking the valley. He doesn't have much to do with everyday life, though; his primary actor is a certain Chang (H.B. Warner), and it is this Chang who explains the ins and outs of life to the survivors, including Robert and his brother George (John Howard), con-man Henry Barnard (Thomas Mitchell), paleontologist Alexander Lovett (Edward Everett Horton), and Gloria Stone (Isabel Jewell), sixth months past her due date for dying of some dread disease. At first, only Robert is terribly excited by the calm sensibility that permeates Shangri-La; he is encouraged in this upon meeting the lovely Sondra (Jane Wyatt), an oddly European-looking resident of the valley. But as the rest find, one by one, that the slow pace and simple needs of life in the valley can be more rewarding than the chaos of the West - and that the valley has some unexplained power that can restore health and prolong life to extraordinary lengths - only George ends up staying angrily insistent that, goddammit, they need to get out of this weird Oriental hell.

So let's knock the unpleasant bit out of the way first. Lost Horizon has a racial politic that almost can't help but make a modern viewer feel a bit queasy - just the yellowface is enough for that, really, but the story grips with particular enthusiasm an idea of hyper-spiritual, Zen-like Asian spirituality that is, at any rate, a lot easier to handle than the notion of ignorant savage hordes of slant-eyed monsters in the Fu Manchu mode. Still, it is by all of the standards of our time - less so by the standards of its own (in fact, the film was later re-edited to downplay its over sympathy for the Chinese, when this became a political liability) - a deprecatory representation that's long on exoticising foreign culture. And this is not true only of the script: there are many shots that find Capra and cinematographer Joseph Walker framing characters and the Stephen Goosson-designed Shangri-La itself with a kind of precious fussiness, one that, on hand, stresses the ethereal nature of the place (which I think to be appropriate and good), and on the other, is deeply invested in making some kind of Orientalist art object of the frame that denies any kind of life or flexibility to the content.

All that being said, this is a fable, not an social documentary, and a certain sense of rich mystery and formalised ritual in the story and the visuals suits the material just fine. After all, the explicit, top-level narrative of Lost Horizon involves a man - a very British man (Colman could play no other kind), that is to say a man who embodies all the things that the phrase "white European colonialist" calls to mind - being thrown into a completely foreign environment and finding that he is entirely the better for it, and that it is a deeply spiritual place to be. The specific trappings do, of course, put Lost Horizon squarely in a tradition of Exotic Other stories, but I am now thinking less of the degree to which, nearly 80 years after its creation, the film matches contemporary tastes, but of how well it functions as a drama driven by its visuals; and I am inclined to say, it does this very well indeed.

One of the things I perpetually re-learn, as I get older and less worked over what films have political and social agendas I agree with, is that Capra - a filmmaker whose politics are very infrequently cotangent with my own - was a talented motherfucker. For all that he's tarred and feathered with the seemingly immortal slur of "Capra-corn", and accused of ticky-tacky sentiment, that criticism only works if you haven't actually seen many Capra films, especially since his most famous work - It's a Wonderful Life, though I wonder how much longer till Mr. Smith Goes to Washington eclipses it - actively repudiates that line of thinking, though many people do not realise this. Not that Lost Horizon is some kind of dour, cynical downer, but it does pretty bluntly suggest that all of "civilisation" - a word that the film unmistakably puts in those exact ironic quotes - is savagery, violence, and base behavior, and what we should hope for is not that some genius will come to save us from ourselves, but that there's a wonderful land far off in the untouchable mountains where a cluster of decent humanity can be saved and groomed until the world is ready for it. The movie says that we all long for a Shangri-La of our own; in so doing, it implies that damn few of us ever get one.

But that has nothing to do with Capra's quality as a filmmaker, of course. What I was starting to say just then was that he's actually quite a gifted craftsman of stirring, interesting visuals, and an extraordinary director of actors - the list of performers who gave their best or near-best performances under his guidance is not a short one, and this film certainly adds Ronald Colman to that list. I have little use for him on the whole: there's a packaged dignity to most of his acting that I find largely indigestible. But his slowly percolating enthusiasm is communicated here with subtlety and restraint, as Capra builds Robert Conway's character through simply watching Colman's feelings move quietly up through his face. And the last act, in which Conway is full of regret, dismay, and fear at the thought of losing his Shangri-La, is simply the best stuff in Colman's career, bleak without being punishing and hopeless.

The other thing that's really extraordinary about the way the film is put together is its use of sound: Dimitri Tiomkin's music especially, but sound effects too. There is a simple, almost primitive scheme used here: when things are chaotic, driven by conflict, or full of negative emotion, the film is loud. When things are serene, thoughtful, reflective, and at peace, the film is quiet. The opening is a violent rebellion, and then the sound drops out to almost nothing but dialogue on the plane. The plane crash is busy and metallic, and then the early scenes in Shangri-La lack even the hint of ambient noise or music. It's elementally powerful, working on an almost wholly subconscious front - and yet, if it's so obvious and simple, why does it feel so unusual? That the film includes virtually nothing on the soundtrack at its most peaceful moments, besides human voices - no birds, no chimes, no wind in the grass - is genuinely startling, but by God, does it work.

Clever filmmaking, and impressively grand filmmaking too: for a hell of an expensive film, Lost Horizon looks it, with massive sets and setpieces, presented by the filmmakers with an eye towards emphasising their scale - the film looks like it takes place in a huge valley surrounded by massive mountains. The use of stock footage from documentaries about the Himalayas certainly aids in this illusion, but it's not the only reason: the mountain sets often seem just as vast, and it should be noted, not without regret, that the studio-shoot footage and the stock footage don't cut together so cleanly, so consistently, that there's much of an illusion to be had, anyway. But setting that aside, it's a sprawling, epic-sized film, and however much Columbia hurt for it, this was money well spent.

And now, a complete change of subject for our final word. As noted, Lost Horizon was generally released at 107 minutes, with 132 minutes being the longest cut that was ever screened for a paying audience. In the '70s and '80s, a massive restoration was attempted, using every scrap of footage that could be scrounged up anywhere in the world. Though a complete soundtrack for the 132-minute cut was found, several minutes of visual information could not, and so the film ends up with several scenes playing out over stills. Meanwhile, the quality of the restored footage is immensely variable, with some of it so blurred and scratched that only context clues make it entirely clear what's going on. To a degree, then, watching the "full" version of Lost Horizon is an act of interpretation: you can gather what's going on and suppose what it might have looked like, but it requires work to get there. And this is not entirely unknown - the reconstructed A Star Is Born from 1954 is exactly the same kind of hybrid.

What is kind of delightful, or at least instructive is seeing the footage that was snipped out, the footage that Cohn deemed inessential. This includes, mind you, the scene where Lama explains his vision of peace and harmony, and clarifies the entire backstory of Shangri-La. So much for an idea-driven movie (it also includes a scene - one of the still photo reconstructions - where the film-long homoeroticism between Henry Barnard and Alexander Lovett sounds to have exploded into full-blown homosexual domesticity. Since this could hardly have been possible in a film made in America in 1937, even one with Edward Everett Horton, the missing visuals must have downplayed things fiercely). Undoubtedly, this moved faster, but that's really the only thing that can be said on its behalf. The longer version of the film is actually a film, with a throughline and clear character moments; yet it is also a compromised Frankenstein monster of passable and unacceptable elements. And so it is with film preservation and restoration: always a situation of coming as close as possible, never actually getting all the way there. Some things, like Shangri-La itself, are hidden away where no one will ever be able to see them again.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1937

-The first cel-animated feature film in history, Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premieres at the end of the year, going on to explode box office records

-Leo McCarey's devastating autumn-years romantic drama Make Way for Tomorrow opens, breaks everybody's heart who sees it

-Daffy Duck makes his first appearance in the Warner Bros. Looney Tune short Porky's Duck Hunt

Elsewhere in World cinema in 1937

-Jean Renoir's magnificent anti-war film Grand Illusion opens in France

-Little-known in the West Yamanaka Sadao's Humanity and Paper Balloons makes a profound impact on the future development of Japanese period dramas, or jidaigeki

-The Polish production The Dybbuk is one of the earliest important works of Yiddish-language filmmaking