's awful nice

A review requested by Monica Reida, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

This article is doing no less than quadruple-duty, so get ready. First, it's of course fulfilling Monica's request to go along with her donation to the ACS. Second, it's plugging another hole in the list of Best Picture Oscar winners, a set of films I'd ultimately like to have reviewed in full. Third, our subject is one of three possible choices for Hit Me with Your Best Shot over at the Film Experience, and fourth, Nathaniel has added a wrinkle this week, in the form of the first-ever and possibly last-ever episode of Hit Me with Your Best Costume.

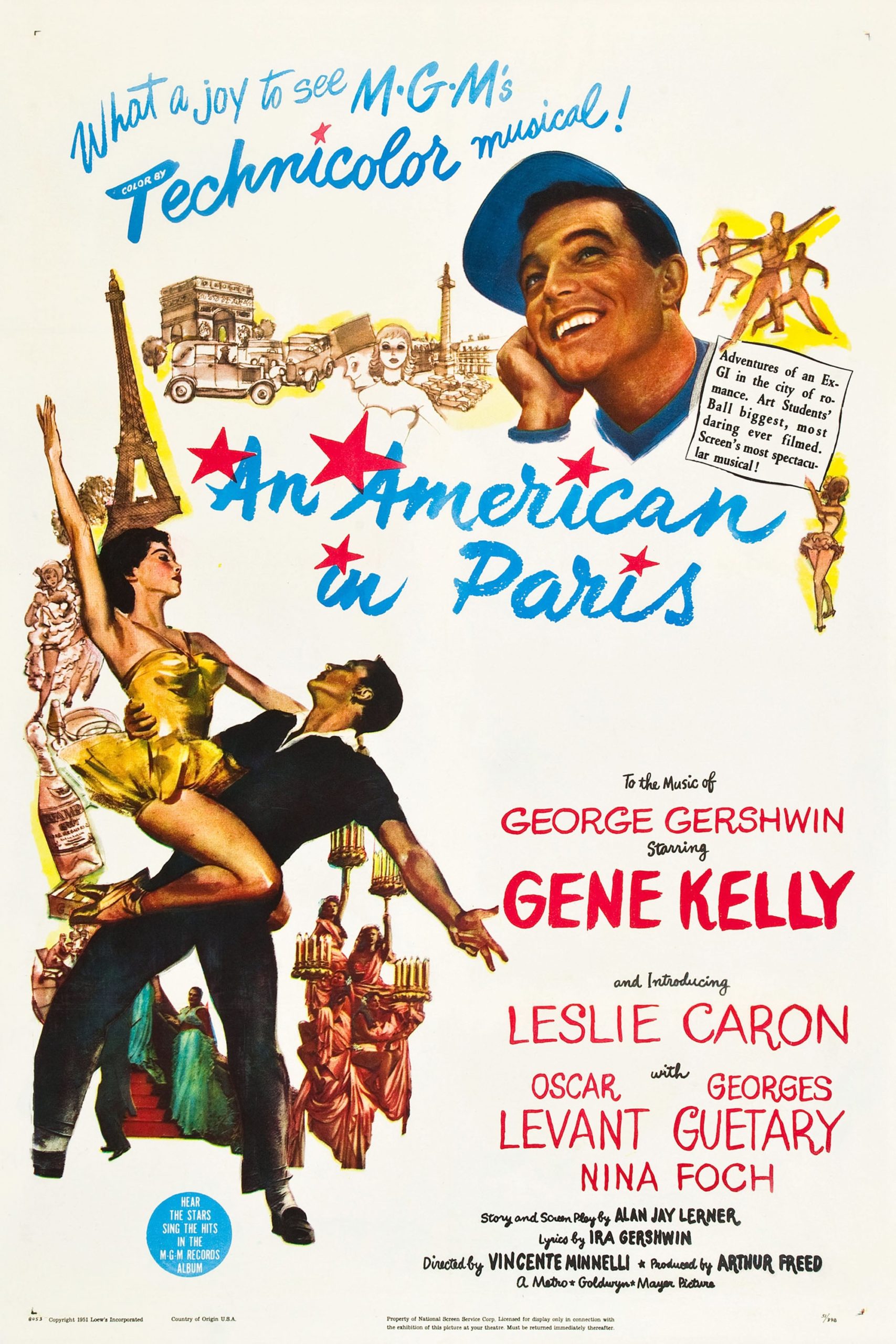

So with all that lined up, let us skip and dance our way over to 1951's An American in Paris, one of the fizziest and most effortlessly delightful trifles of a film ever to be broadly disliked on account of beating some other film for the Oscar (A Streetcar Named Desire, in this case, though I contend that A Place in the Sun is the best of the nominees, and I'd have been an American voter over Streetcar if I had to pick). Oh well, it's their loss.

In fairness, the problems with An American in Paris are hardly difficult to spot, mostly to do with its Alan Jay Lerner screenplay. It's a featherweight, gossamer thing, languidly stretching hardly any conflict across two hours mostly through the strategy of frequently dropping in extended sequences in which literally nothing happens. There are so many of these interludes that I suspect it's impossible that this was anything other than a deliberate choice: befitting its title and inspiration (an 18-minute tone poem written in 1928 by George Gershwin attempting to musically summarise his impressions of life in Jazz Age France), the film is in large part a plotless saunter through the places and people encountered and enjoyed by an American in, well, you know. Jerry Mulligan (Gene Kelly) is at once too entrenched in the life of post-war Paris to count as a tourist, but he's still a foreigner through and through, leaving him stuck somewhere outside the culture he admires and enjoys from arm's length. Much of An American in Paris examines, quite without making a fuss about it, what the city appears like from that perspective, and that's what you get from all those structurally disastrous scenes of Jerry poking around in corners.

It's probably an accident that this story of an American trying to fit into the culture of post-war Europe should mirror his efforts through its own aesthetic, but there seems like something of the faintest echo of Italian and French cinema from the same post-war period in the way that An American in Paris contents itself to stop and watch people simply being without feeling the need to force their being-ness into a tight narrative design. Of course, the film was still shot on sets at MGM by producer Arthur Freed's famously lavish production unit, under the direction of lush stylist Vincente Minnelli - neorealism it ain't. But by Freed Unit standards, this is damn near grubby for most of its running time, and for a solid hour almost completely free of even a hint of melodrama.

Such plot as the movie has follows Jerry's attempts to make it as a successful painter, garnering admiring nods but no money for his art (it's impossible to say if the movie expects us to regard his paintings as the run-of-the-mill neo-impressionist Parisian landscapes they so very much are, but ultimately his talent is completely beside any point). This changes when he catches the eye of a wealthy, young, attractive heiress named Milo Roberts (Nina Foch); Jerry has no desire to be anybody's gigolo, but he has less of a desire to starve to death, so he only vaguely discourages her flirtation and, later, her professional assistance. Jerry's got an American buddy also trying to hack it in Paris, pianist Adam Cook (Oscar Levant), and Adam is tight with an up-and-coming French singer, Henri "Hank" Baurel (George Guétary), who has of late been courting a charming shopgirl, Lise Bouvier (Leslie Caron), whose affection for him is more sisterly than amorous, but she's permitted herself to play-act at falling in love with him, in the absence of any hunky Americans to sweep her off her feet. Then one night, Jerry and Lise meet at a club.

It's simple enough, and anyway I've already proposed that the film is mostly interested in capturing a broad sense of Paris, circa 1951, rather than relating a strikingly original romantic plot; it's a little disheartening that with so little to do, the script still doesn't quite do it. The film opens with a baffling choice to give Jerry, Adam, and Hank a minute or two of voiceover narration to establish themselves and their role in the burgeoning artistic life of post-war Paris, with the camera actually adopting Hank's physical position for a brief tracking shot, which is even more baffling; it also relies a lot on the old "if you're watching the leads in a musical, you just expect them to fall in love" to avoid having to fully flesh out the early scenes between Jerry and Lise, which it seems clear that the film, if not the filmmakers, view as an imposition on the much more rewarding dog-ends of scenes exploring Paris. And the ending is one of the all-time great con jobs in Hollywood history, coming after-

...well, at some point I was going to have to dive into it. An American in Paris is extraordinarily charming. It has a terrific soundtrack, as films will when they are musical culled exclusively from the songbook of George and Ira Gershwin. There's some really phenomenal choreography by Kelly, who had firmly established himself as one of Hollywood's preeminent choreographers over the preceding five years, especially on the backs of The Pirate in 1948 and On the Town in 1949. Without discounting the Minnelli-ness of the sweet attitude and razor-sharp use of color, the Freed-ness of the gigantic production scale, and the (not always welcome) Lerner-ness of the twee script, I believe it is not inaccurate to suggest that this is a film in service to Kelly's vision: when the film slows down, like as not it's to take in one of his numbers, and the very Kelly-esque attitude on display in the dancing infects everything else. The first proper dance number, "By Strauss", finds the choreographer incorporating a whole room full of extras, giving some nice old ladies a chance to have fun dancing a reasonably stripped-down routine; the next song after that, "I Got Rhythm", hands much of the action over to a group of kids. There is a great democracy involved in these moments, and opening up dance to everybody, whether as participant or artist, was one of Kelly's animating interests (see, for example, the mostly inept but beautifully earnest and eager Invitation to the Dance). Less simply, but no less beautifully, Kelly provides a moderately complex dance for himself and Caron, set to "Our Love is Here to Stay", and set on the banks of the fake Seine. Much of An American in Paris consists of nothing but paying tribute to the joy that singing and dancing provide in the moment, and that is just a delightful, wonderful thing.

So again: charming. Extraordinarily charming, I believe I said. If it was 96 minutes long, I think that charm would be enough to put it in most people's top third of all MGM musicals, though you'd have to be the person who'd seen enough MGM musicals to have a top third in order to even know it existed. It would probably not have won the Oscar, which I think would have have made it hard for it to live on as an established classic. But it is not 96 minutes long. It is 113 minutes long, and those 17 minutes extra are almost certainly the finest extended stretch of American filmmaking in the 1950s. For that is where we find the "An American in Paris" ballet, and it is beyond divine. If An American in Paris was just a short film and it contained nothing but the ballet, that would be enough to earn it a spot in the "best movies ever made" conversation - the rest of the film, honestly, is in some ways nothing but a framework to get us to the ballet.

It is more or less the same story as the film containing it: Jerry meanders around a market, finds Lise, falls in love with her, and then she abruptly vanishes after an interlude that he thinks meant true love. But it is so much more striking in its abstraction than the rest is in its cheerful shuffling of well-worn tropes. The combination of Gershwin's music (full disclosure: "An American in Paris" is one of my dozen or so favorite pieces of music from the 20th Century, which surely makes me an easy mark for the ballet) and the wide scope of choreography techniques from Kelly's grab bag - classical ballet, jazz, tap, even a splash of can-can - make for a phenomenal piece of populist art. And I do use the word "populist" with some intent: like "An American in Paris" itself, the ballet here is not trying to prove itself to the connoisseur, but make something special for the groundlings.

It's inconceivable that Kelly hadn't seen Rodgers & Hammerstein's 1943 musical Oklahoma!, with its groundbreaking dream ballet; I suppose that his goal with this ballet was do to for movie musicals what that show did for stage musicals, radically expanding the set of available storytelling tools into a whole new medium, all in one push. If he did intend such a thing, he got his wish; An American in Paris led to an immediate vogue for huge extended ballet-style production numbers with no connection to the plot, something that hadn't been seen really since Busby Berkeley's great pre-Code masterpieces. The most familiar of these are probably Singin' in the Rain's "Broadway Melody", The Band Wagon's "Girl Hunt", and over at Warner's, A Star Is Born's singing-heavy "Born in a Trunk", and two of those are masterpieces in their own right (apologies, "Girl Hunt"; love the sets and cinematography, but you make Fred Astaire look faintly ludicrous). But they're nothing on "An American in Paris", not at the level of storytelling nor filmmaking nor pure "go for it with all you've got" talent - for "An American in Paris" finds Kelly working at a level he'd never been and would never really return to, and for as much as I love several numbers in Singin' in the Rain, none of them are playing at this level of world-beating ambition.

"An American in Paris" is an astonishment on every level. First, we notice the eruption of color: after a movie that has been almost exclusively doled out in shades of brown since the searing Technicolor of the fantasy sequence introducing Lise in a series of balletic cutaways in solid-color rooms, we are thrust into a world of gorgeous, oversaturated blue, white, and red, before noting that each phase of the dance shifts the color palette: sometimes in the sexy golds and reds of twilight, sometimes in the florid pinks, purples, and oranges of Paris in the springtime, sometimes a cool white-on-grey to accentuate a sense of pessimistic confusion. Minnelli wasn't no dope when it came to using color in a way that would have the strongest possible effect on the audience, and An American in Paris, in that one moment of its huge swing from naturalistic to utterly fantastic colors, is just about his masterpiece in that regard.

Then there is the emotional component of the dance, the way it springboards off of Gershwin to explore a wide range of bittersweet and joyful feelings ranging from intoxicated romance to outright depression. And with that, I would like to finally share with you my choice for the film's best shot, which is just such a moment of depression:

Look, An American in Paris is cake. Not its biggest defender would deny that - hell, I'm its biggest defender that I know of, and I'm telling you, right now, this film will give you cavities and has absolutely no nutritional content. But there, sometimes, hiding right inside the movie, you get a moment like this one, so sublimely depicting in one tableaux a genuinely bitter and broken feeling: the self-isolating misery of a man who has hit the skids romantically, and found that everything is miserable. The feeling does not last - mere seconds after rebuffing the four giddy military men trying to drag him out for a day on the town, Jerry gives in and dances into the clothing shop to put on a vivid red coat. But for those few seconds, the effervescent, sugary joy of the movie parts ways for just long enough to reveal a disquieting depiction of honest-to-God depression, when all you want to do is to be left along, to specifically not have fun, because having fun is just stupid bullshit.

I can't come up with a nice segue to my pick for the best of Orry-Kelly's costumes, but it happens in the very next scene, so here it is:

It's probably the most famous thing Caron wears in the movie, so no points for originality. But I love about it the way that it feels unmistakably "French" in a way that you can't quite pin down. Is it the hat? It is it the lack of sleeves? Ooh, I think it's actually the gloves, which I just noticed, like really noticed for the first time. It's also unmistakably multicolored, but not in the way the Kelly and the boys' rainbow of sport coats are multi-colored. It's, somehow, like if all the colors contributed to black, not to white.

Overall, it's a weird combination of the excessive with the subdued (all that Technicolor used in ways that are quiet and subdued rather than bold and overwhelming) and the juvenile with the mature (the hat makes the girlish Caron look even more so, while the form-fitting lines and accent on her waist call attention to her body and almost sexualise it; but actually sexualising the Eternal Virgin Caron would take a few more years and much less crowd-pleasing movies than this).

The whole of the "American in Paris" ballet is full of the most dynamic design, of sets and costumes and color, and its emotional palette is affecting in ways that, for the most part, the movie itself isn't: first-time movie actor Caron isn't a hopeless, and I think Minnelli would later come up with some fairly nervy minor keys for her to play in another fizzy French musical, Gigi, but neither he nor she was up to that at this point. It leaves one-half of the film's romantic partnership flat, and Kelly doesn't pick up the slack: he was always a bundle of charisma and warm smiles, and his genial chemistry with the film's old ladies and darling French moppets proves that he was ready to bring his A-game as an actor, however besotted with his own charm he tends to be. But he's only ever particularly good at sparking with his female leads when they can do most of the work (he's generally great with his male co-stars, and Levant is no exception here): outside of Debbie Reynolds in Singin' in the Rain, which was anyway a whole film's worth of things that shouldn't succeed turning out sublimely, he's only really effective as a romantic lead opposite Judy Garland, whose palpable, self-destroying need to be loved draws something focused and real from Kelly's slick presence.

So the romantic A-plot doesn't do a whole lot for me. But re-run it in the form of dance, and it is heartbreaking and beautiful, and I have all the hairs on my arms standing at attention just thinking of some of the shots and some of the movements in the ballet.

That's ultimately part of why I called this a con job. Remember how I called this a con job, like, 6000 words ago? It's because of two things: one is that An American in Paris doesn't have an ending, and it doesn't do the right emotional heavy lifting to earn the ending it doesn't have. SPOILER ALERT for a 65-year-old movie with exactly the ending you predict it to have: so Lise goes away with Hank, and Jerry stands watching his guts splash out on the ground in front of his feet, and he drifts into a reverie where he imagines his entire time in Paris as a fantasy in which he falls in love and loses love, and he ends with a look of stupefied horror even in his daydream. He then opens his eyes and Lise comes running up to him, with Hank having had an apparent change of heart upon realising that she didn't love him. This takes less than 90 seconds, from the end of the ballet to "The End: Made in Hollywood, USA by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer". It makes absolutely no sense whatsoever other than pure emotional Hollywood logic: we want them together, we're watching a movie, so they shall end up together. It's not inexplicable: we've seen Hank's discomfort at knowing that Lise only respects him, but loves Jerry. It's just very, very fast, and very, very arbitrary.

And An American in Paris gets away with it scot-free. Part of it is simply because it has taken a 17-minute pause, and we can conceive of more or less whatever we want filling those 17 minutes; likeliest of all is that we've just forgotten. The bigger part, I think, is that the opening 95 minutes of An American in Paris encourage us to want a "story" ending: we want to see Lise's sadness and Hank's sacrifice, we want Jerry to run out into the Paris night bemoaning his loss. Minutes 96-112 retrain us: they present a world of essentialised, bold-color emotions presented in pantomime and gesture. More importantly, they are much more engaging than the 95 minutes preceding, so that we are more worked up by that shot of a despairing Kelly clutching a rose to his chest than we are by whatever the last plot beat prior to the ballet. Jerry tears up one of his drawings, I think. So what we really want from the ending of the film isn't a concrete "story" ending, but an emotional, gestural "ballet" ending. And that's what we get: even the cross-cutting between Jerry and Lise on the stairs is more about their movements than anything else. Plus, the last minute of the score is a whirlwind recap of the entire 17-minute tone poem, reminding us more of the ballet than anything else. It is a totally unacceptable ending, but it's exactly the one that An American in Paris needs and earns - it is contrived and shamefully dishonest Hollywood hokum at its most bravura and therefore most overwhelming. I think you can only despise this or love it - I love it. The first three-quarters of An American in Paris might be at best B-tier Freed Unit filmmaking, but those last 18 minutes are as precious to me as anything produced by studio-era Hollywood.

This article is doing no less than quadruple-duty, so get ready. First, it's of course fulfilling Monica's request to go along with her donation to the ACS. Second, it's plugging another hole in the list of Best Picture Oscar winners, a set of films I'd ultimately like to have reviewed in full. Third, our subject is one of three possible choices for Hit Me with Your Best Shot over at the Film Experience, and fourth, Nathaniel has added a wrinkle this week, in the form of the first-ever and possibly last-ever episode of Hit Me with Your Best Costume.

So with all that lined up, let us skip and dance our way over to 1951's An American in Paris, one of the fizziest and most effortlessly delightful trifles of a film ever to be broadly disliked on account of beating some other film for the Oscar (A Streetcar Named Desire, in this case, though I contend that A Place in the Sun is the best of the nominees, and I'd have been an American voter over Streetcar if I had to pick). Oh well, it's their loss.

In fairness, the problems with An American in Paris are hardly difficult to spot, mostly to do with its Alan Jay Lerner screenplay. It's a featherweight, gossamer thing, languidly stretching hardly any conflict across two hours mostly through the strategy of frequently dropping in extended sequences in which literally nothing happens. There are so many of these interludes that I suspect it's impossible that this was anything other than a deliberate choice: befitting its title and inspiration (an 18-minute tone poem written in 1928 by George Gershwin attempting to musically summarise his impressions of life in Jazz Age France), the film is in large part a plotless saunter through the places and people encountered and enjoyed by an American in, well, you know. Jerry Mulligan (Gene Kelly) is at once too entrenched in the life of post-war Paris to count as a tourist, but he's still a foreigner through and through, leaving him stuck somewhere outside the culture he admires and enjoys from arm's length. Much of An American in Paris examines, quite without making a fuss about it, what the city appears like from that perspective, and that's what you get from all those structurally disastrous scenes of Jerry poking around in corners.

It's probably an accident that this story of an American trying to fit into the culture of post-war Europe should mirror his efforts through its own aesthetic, but there seems like something of the faintest echo of Italian and French cinema from the same post-war period in the way that An American in Paris contents itself to stop and watch people simply being without feeling the need to force their being-ness into a tight narrative design. Of course, the film was still shot on sets at MGM by producer Arthur Freed's famously lavish production unit, under the direction of lush stylist Vincente Minnelli - neorealism it ain't. But by Freed Unit standards, this is damn near grubby for most of its running time, and for a solid hour almost completely free of even a hint of melodrama.

Such plot as the movie has follows Jerry's attempts to make it as a successful painter, garnering admiring nods but no money for his art (it's impossible to say if the movie expects us to regard his paintings as the run-of-the-mill neo-impressionist Parisian landscapes they so very much are, but ultimately his talent is completely beside any point). This changes when he catches the eye of a wealthy, young, attractive heiress named Milo Roberts (Nina Foch); Jerry has no desire to be anybody's gigolo, but he has less of a desire to starve to death, so he only vaguely discourages her flirtation and, later, her professional assistance. Jerry's got an American buddy also trying to hack it in Paris, pianist Adam Cook (Oscar Levant), and Adam is tight with an up-and-coming French singer, Henri "Hank" Baurel (George Guétary), who has of late been courting a charming shopgirl, Lise Bouvier (Leslie Caron), whose affection for him is more sisterly than amorous, but she's permitted herself to play-act at falling in love with him, in the absence of any hunky Americans to sweep her off her feet. Then one night, Jerry and Lise meet at a club.

It's simple enough, and anyway I've already proposed that the film is mostly interested in capturing a broad sense of Paris, circa 1951, rather than relating a strikingly original romantic plot; it's a little disheartening that with so little to do, the script still doesn't quite do it. The film opens with a baffling choice to give Jerry, Adam, and Hank a minute or two of voiceover narration to establish themselves and their role in the burgeoning artistic life of post-war Paris, with the camera actually adopting Hank's physical position for a brief tracking shot, which is even more baffling; it also relies a lot on the old "if you're watching the leads in a musical, you just expect them to fall in love" to avoid having to fully flesh out the early scenes between Jerry and Lise, which it seems clear that the film, if not the filmmakers, view as an imposition on the much more rewarding dog-ends of scenes exploring Paris. And the ending is one of the all-time great con jobs in Hollywood history, coming after-

...well, at some point I was going to have to dive into it. An American in Paris is extraordinarily charming. It has a terrific soundtrack, as films will when they are musical culled exclusively from the songbook of George and Ira Gershwin. There's some really phenomenal choreography by Kelly, who had firmly established himself as one of Hollywood's preeminent choreographers over the preceding five years, especially on the backs of The Pirate in 1948 and On the Town in 1949. Without discounting the Minnelli-ness of the sweet attitude and razor-sharp use of color, the Freed-ness of the gigantic production scale, and the (not always welcome) Lerner-ness of the twee script, I believe it is not inaccurate to suggest that this is a film in service to Kelly's vision: when the film slows down, like as not it's to take in one of his numbers, and the very Kelly-esque attitude on display in the dancing infects everything else. The first proper dance number, "By Strauss", finds the choreographer incorporating a whole room full of extras, giving some nice old ladies a chance to have fun dancing a reasonably stripped-down routine; the next song after that, "I Got Rhythm", hands much of the action over to a group of kids. There is a great democracy involved in these moments, and opening up dance to everybody, whether as participant or artist, was one of Kelly's animating interests (see, for example, the mostly inept but beautifully earnest and eager Invitation to the Dance). Less simply, but no less beautifully, Kelly provides a moderately complex dance for himself and Caron, set to "Our Love is Here to Stay", and set on the banks of the fake Seine. Much of An American in Paris consists of nothing but paying tribute to the joy that singing and dancing provide in the moment, and that is just a delightful, wonderful thing.

So again: charming. Extraordinarily charming, I believe I said. If it was 96 minutes long, I think that charm would be enough to put it in most people's top third of all MGM musicals, though you'd have to be the person who'd seen enough MGM musicals to have a top third in order to even know it existed. It would probably not have won the Oscar, which I think would have have made it hard for it to live on as an established classic. But it is not 96 minutes long. It is 113 minutes long, and those 17 minutes extra are almost certainly the finest extended stretch of American filmmaking in the 1950s. For that is where we find the "An American in Paris" ballet, and it is beyond divine. If An American in Paris was just a short film and it contained nothing but the ballet, that would be enough to earn it a spot in the "best movies ever made" conversation - the rest of the film, honestly, is in some ways nothing but a framework to get us to the ballet.

It is more or less the same story as the film containing it: Jerry meanders around a market, finds Lise, falls in love with her, and then she abruptly vanishes after an interlude that he thinks meant true love. But it is so much more striking in its abstraction than the rest is in its cheerful shuffling of well-worn tropes. The combination of Gershwin's music (full disclosure: "An American in Paris" is one of my dozen or so favorite pieces of music from the 20th Century, which surely makes me an easy mark for the ballet) and the wide scope of choreography techniques from Kelly's grab bag - classical ballet, jazz, tap, even a splash of can-can - make for a phenomenal piece of populist art. And I do use the word "populist" with some intent: like "An American in Paris" itself, the ballet here is not trying to prove itself to the connoisseur, but make something special for the groundlings.

It's inconceivable that Kelly hadn't seen Rodgers & Hammerstein's 1943 musical Oklahoma!, with its groundbreaking dream ballet; I suppose that his goal with this ballet was do to for movie musicals what that show did for stage musicals, radically expanding the set of available storytelling tools into a whole new medium, all in one push. If he did intend such a thing, he got his wish; An American in Paris led to an immediate vogue for huge extended ballet-style production numbers with no connection to the plot, something that hadn't been seen really since Busby Berkeley's great pre-Code masterpieces. The most familiar of these are probably Singin' in the Rain's "Broadway Melody", The Band Wagon's "Girl Hunt", and over at Warner's, A Star Is Born's singing-heavy "Born in a Trunk", and two of those are masterpieces in their own right (apologies, "Girl Hunt"; love the sets and cinematography, but you make Fred Astaire look faintly ludicrous). But they're nothing on "An American in Paris", not at the level of storytelling nor filmmaking nor pure "go for it with all you've got" talent - for "An American in Paris" finds Kelly working at a level he'd never been and would never really return to, and for as much as I love several numbers in Singin' in the Rain, none of them are playing at this level of world-beating ambition.

"An American in Paris" is an astonishment on every level. First, we notice the eruption of color: after a movie that has been almost exclusively doled out in shades of brown since the searing Technicolor of the fantasy sequence introducing Lise in a series of balletic cutaways in solid-color rooms, we are thrust into a world of gorgeous, oversaturated blue, white, and red, before noting that each phase of the dance shifts the color palette: sometimes in the sexy golds and reds of twilight, sometimes in the florid pinks, purples, and oranges of Paris in the springtime, sometimes a cool white-on-grey to accentuate a sense of pessimistic confusion. Minnelli wasn't no dope when it came to using color in a way that would have the strongest possible effect on the audience, and An American in Paris, in that one moment of its huge swing from naturalistic to utterly fantastic colors, is just about his masterpiece in that regard.

Then there is the emotional component of the dance, the way it springboards off of Gershwin to explore a wide range of bittersweet and joyful feelings ranging from intoxicated romance to outright depression. And with that, I would like to finally share with you my choice for the film's best shot, which is just such a moment of depression:

Look, An American in Paris is cake. Not its biggest defender would deny that - hell, I'm its biggest defender that I know of, and I'm telling you, right now, this film will give you cavities and has absolutely no nutritional content. But there, sometimes, hiding right inside the movie, you get a moment like this one, so sublimely depicting in one tableaux a genuinely bitter and broken feeling: the self-isolating misery of a man who has hit the skids romantically, and found that everything is miserable. The feeling does not last - mere seconds after rebuffing the four giddy military men trying to drag him out for a day on the town, Jerry gives in and dances into the clothing shop to put on a vivid red coat. But for those few seconds, the effervescent, sugary joy of the movie parts ways for just long enough to reveal a disquieting depiction of honest-to-God depression, when all you want to do is to be left along, to specifically not have fun, because having fun is just stupid bullshit.

I can't come up with a nice segue to my pick for the best of Orry-Kelly's costumes, but it happens in the very next scene, so here it is:

It's probably the most famous thing Caron wears in the movie, so no points for originality. But I love about it the way that it feels unmistakably "French" in a way that you can't quite pin down. Is it the hat? It is it the lack of sleeves? Ooh, I think it's actually the gloves, which I just noticed, like really noticed for the first time. It's also unmistakably multicolored, but not in the way the Kelly and the boys' rainbow of sport coats are multi-colored. It's, somehow, like if all the colors contributed to black, not to white.

Overall, it's a weird combination of the excessive with the subdued (all that Technicolor used in ways that are quiet and subdued rather than bold and overwhelming) and the juvenile with the mature (the hat makes the girlish Caron look even more so, while the form-fitting lines and accent on her waist call attention to her body and almost sexualise it; but actually sexualising the Eternal Virgin Caron would take a few more years and much less crowd-pleasing movies than this).

The whole of the "American in Paris" ballet is full of the most dynamic design, of sets and costumes and color, and its emotional palette is affecting in ways that, for the most part, the movie itself isn't: first-time movie actor Caron isn't a hopeless, and I think Minnelli would later come up with some fairly nervy minor keys for her to play in another fizzy French musical, Gigi, but neither he nor she was up to that at this point. It leaves one-half of the film's romantic partnership flat, and Kelly doesn't pick up the slack: he was always a bundle of charisma and warm smiles, and his genial chemistry with the film's old ladies and darling French moppets proves that he was ready to bring his A-game as an actor, however besotted with his own charm he tends to be. But he's only ever particularly good at sparking with his female leads when they can do most of the work (he's generally great with his male co-stars, and Levant is no exception here): outside of Debbie Reynolds in Singin' in the Rain, which was anyway a whole film's worth of things that shouldn't succeed turning out sublimely, he's only really effective as a romantic lead opposite Judy Garland, whose palpable, self-destroying need to be loved draws something focused and real from Kelly's slick presence.

So the romantic A-plot doesn't do a whole lot for me. But re-run it in the form of dance, and it is heartbreaking and beautiful, and I have all the hairs on my arms standing at attention just thinking of some of the shots and some of the movements in the ballet.

That's ultimately part of why I called this a con job. Remember how I called this a con job, like, 6000 words ago? It's because of two things: one is that An American in Paris doesn't have an ending, and it doesn't do the right emotional heavy lifting to earn the ending it doesn't have. SPOILER ALERT for a 65-year-old movie with exactly the ending you predict it to have: so Lise goes away with Hank, and Jerry stands watching his guts splash out on the ground in front of his feet, and he drifts into a reverie where he imagines his entire time in Paris as a fantasy in which he falls in love and loses love, and he ends with a look of stupefied horror even in his daydream. He then opens his eyes and Lise comes running up to him, with Hank having had an apparent change of heart upon realising that she didn't love him. This takes less than 90 seconds, from the end of the ballet to "The End: Made in Hollywood, USA by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer". It makes absolutely no sense whatsoever other than pure emotional Hollywood logic: we want them together, we're watching a movie, so they shall end up together. It's not inexplicable: we've seen Hank's discomfort at knowing that Lise only respects him, but loves Jerry. It's just very, very fast, and very, very arbitrary.

And An American in Paris gets away with it scot-free. Part of it is simply because it has taken a 17-minute pause, and we can conceive of more or less whatever we want filling those 17 minutes; likeliest of all is that we've just forgotten. The bigger part, I think, is that the opening 95 minutes of An American in Paris encourage us to want a "story" ending: we want to see Lise's sadness and Hank's sacrifice, we want Jerry to run out into the Paris night bemoaning his loss. Minutes 96-112 retrain us: they present a world of essentialised, bold-color emotions presented in pantomime and gesture. More importantly, they are much more engaging than the 95 minutes preceding, so that we are more worked up by that shot of a despairing Kelly clutching a rose to his chest than we are by whatever the last plot beat prior to the ballet. Jerry tears up one of his drawings, I think. So what we really want from the ending of the film isn't a concrete "story" ending, but an emotional, gestural "ballet" ending. And that's what we get: even the cross-cutting between Jerry and Lise on the stairs is more about their movements than anything else. Plus, the last minute of the score is a whirlwind recap of the entire 17-minute tone poem, reminding us more of the ballet than anything else. It is a totally unacceptable ending, but it's exactly the one that An American in Paris needs and earns - it is contrived and shamefully dishonest Hollywood hokum at its most bravura and therefore most overwhelming. I think you can only despise this or love it - I love it. The first three-quarters of An American in Paris might be at best B-tier Freed Unit filmmaking, but those last 18 minutes are as precious to me as anything produced by studio-era Hollywood.