Hollywood Century, 1952: In which we find that the classically boyish genre of the Western has decided to grow up

The next time you're at a cocktail party, and the hostess stands up tipsily and imperiously like Rosalind Russell in Auntie Mame to demand that everybody share their favorite actor-director team,* I want you to do me a favor. Overlook the obvious (De Niro and Scorsese), the tasteless (Depp and Burton), the snobby (Ullmann and Bergman), the classic (Flynn and Curtiz), and the snobbily classicist (Dietrich and von Sternberg). Even if your head happens to be in a Western state of mind, I'd ask you to check the impulse to say the Johns Wayne and Ford. Instead, I would be so bold as to gently nudge you in the direction of all-American Everyfella James Stewart and lean, muscular genre master Anthony Mann, who made eight films together in the 1950s, five of them Westerns, and those among the most starkly modernist, elegantly savage films that genre would ever know until the Italians started in with their displays of hyperviolence in the mid-'60s.

We shall not in this moment recount the entire history of their collaboration, tarrying to mention only that their first work, 1950's Winchester '73 was something of a watershed moment in both the development of the Western and in the evolution of Stewart's career. Prior to serving as a highly-decorated bomber in World War II, the actor had played a lot of breezy, charming, idealistic roles in a breezy, charming, idealistic way, but the shock and horror of what he encountered during the war years changed him immensely: his first movie back was It's a Wonderful Life, everybody's favorite heart-warming Christmas parable about hanging on through a potent fit of suicidal depression, and most of his movies remained tinged by death, psychosis, and suffering forever after. Teaming with Mann, already establishing himself as the creator of blunt, masculine films depicting and anatomising human cruelty, was perhaps not the inevitable nor natural next step, but it worked out splendidly: Winchester '73 is both Mann's first unassailable great film and the first role for Stewart that actively flaunted and mocked his kindly persona, suggesting that being an Old West hero took the kind of tough asshole that circumstances only, and not morality or decency, permitted to emerge as "heroic".

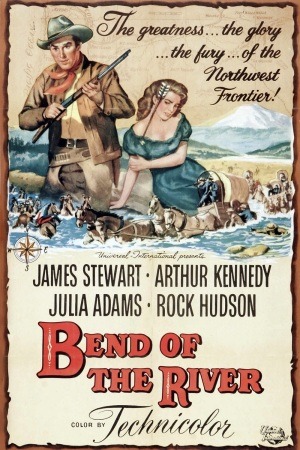

It's a great film and it made a good showing for itself at the box office, so a follow-up was inevitable. It came in the form of 1952's Bend of the River, a film that generally plays things a bit more respectfully, with less complicated morality, a more conventional story, and lavish Technicolor cinematography to capture the lush Oregon shooting locations, in place of the lightly noir-flavored black-and-white in Winchester '73. All of which makes it feel less of a live-wire than the other Mann/Stewart Westerns, and I don't see much of a way around declaring it the weakest of their five collaborations in the genre. Though that says much more about the superlative quality of the other films than it points out any particular weakness in Bend of the River itself: on its own merits, this is still a top-notch movie with a clear method to its surprisingly bleak depiction of violence, however beholden Borden Chase's script (great name for a Western writer) is in some places to genre clichés that do it no favors as a story or as a depiction of a society (the casually racist "the Injuns are attacking!" scene, in particular, stands out as a lazy crutch that only exists to advance a single plot point, and makes it clear just how much more progressive Ford's films of the same vintage could be than they're typically given credit for).

The film opens east of the Rockies: here we find Glyn McLyntock (Stewart), a weathered trail guide leading a wagon train of Missouri farmers west to Oregon, where they plan on building a little slice of domesticity for themselves. McLyntock is a transparent Man With A Past, though the nature of that past is only slowly revealed to us, and then almost purely through innuendo and implication. But the hints start immediately, when he happens upon a lynch mob during one of his scouting trips: a group of trappers are in the process of hanging Emerson Cole (Arthur Kennedy) for stealing horses, and without even stopping to figure out whether this is true, McLyntock interrupts this swift country justice with an authoritative snarl.

Cheyenne attacks and nascent romantic triangles between McLyntock, Cole and Laura Baile (Julie Adams) fill up the rest of the trip to the rough frontier town of Portland, where the farmers buy the first wave of supplies to overwinter; Laura has to stay behind to nurse a shoulder wound sustained in the attack, and Cole drifts away to seek his fortune in California. McLyntock joins the riverboat trek through treacherous waters to the fertile lands around the …wait for it… bend of the river, but when winter looms and the back-up supplies doesn't show, he and Laura's father, and the de facto leader of the farmers, Jeremy (Jay C. Flippen) head back to Portland, where they find that a gold rush has transformed the peaceful, rural West into a hellhole of greed, lust, and violence. McLyntock, who we've sussed out by now was a border raider during the Civil War, has enough of the killer left in his soul that he's equipped to deal with this situation, and even when he hires a transparently shady team of ruffians to help sneak the farmers' supplies away from an avaricious mercantilist, it's clear that he's well aware of the possibility that a bit of betrayal and violence might erupt on the way, to be dealt with however they must.

It's a straightforward story of redemption: never really asking whether a violent man who is regretful in his heart can actually succeed at being moral and just, but more than slightly unsure if such a man will ever be trusted by the Nice People. That's the actual tension between McLyntock and Cole: not whether a former border raider can change his path, but whether the cynicism of others will cause him to change it right back. It's giving away very little that Stewart doesn't clearly foreshadow through his calm, level performance that Bend of the River adopts a mostly optimistic attitude towards this topic, but getting there requires a shocking amount of on-screen bloodshed for '52 (figurative bloodshed: we see bodies, but never the red stuff), and a cold-bloodedness from Stewart that's intensely shocking coming from the face and voice of Jeff Smith, Macaulay Connor and George Bailey.

There's a moment, late in the movie, that represents perhaps the exact moment that the Early, Pleasant Stewart is finally and irrevocably dropped in favor of New, Harsh Stewart, a moment that competes with anything in Vertigo for thoroughly undoing any viewer who comes into the movie with visions of Midwestern optimism dancing in their heads: "You'll be seeing me. You'll be seeing me. Every time you bed down for the night, you'll look back to the darkness and wonder if I'm there. And some night, I will be. You'll be seeing me!" McLyntock hisses, with venom on his tongue and ice-cold hate in his eyes. It's like Stewart was pouring every negative emotion he felt over the past ten years into that one moment, his whole body arched like a big cat ready to pounce, and his words delivered with no emphasis or size, just low boiling menace. If there's one single instant in the Mann/Stewart films that crystallises the theme of all of them - there are times and places where only the real bastards can possibly survive, and the best bastards are simply the ones with enough humanity to recognize their own incivility - this is that moment.

That moment is houses inside a film that is, all in all, a little bit less complicated than one might wish it to be. It is a terrific Western, but it feels constrained by the genre in a way that Winchester '73 doesn't, and the later The Naked Spur and The Man from Laramie really especially don't. The music by Hans J. Salter does it no favors: all stock-issue "This here is the Wild West, and them thar's Indians!" cues, fine for getting the pulse racing but not really for teasing out the nasty moral complexity in the central characters. And meanwhile, that moral complexity is only in the central characters: the plainspoken nobility of the farmers, and their dogged determination to carve out a home on the unforgiving frontier is given lopsided prominence in every possible way over the venal, greedy, violent, whoring miners: the script implies it, the beatific performance of Flippen contrasted with just about everybody else in the film insists on it, the lighting - Portland as the den of gold rush hedonism is shot in pitch nighttime blacks, while the farming scenes, and Portland as the cozy last sign of civilisation, take place in broad daylight - demands it. Not that the story really would benefit from muddying that morality anyway, in blunt narrative terms, but the greyness and ambivalence baked into the McLyntock/Cole story makes the stark "farm good, gold bad" depiction of the background story seem disappointingly unadventurous and square.

There are also the inevitable representational issues that one can't help but expect from a film, in a white man's genre, from 1952. As is not uncommon with Mann, women serve as totems rather than personalities; the whole movie knows that it's occupying a mythic space in which characters tend to function as representatives of a concept, and this keeps it from being quite as unpleasant to modern tastes as plenty of other Westerns throughout history, but thoroughness demands I mention it. Girls are props and trophies and symbols of the men's development; there's no way around it. Far more inexplicable (because after all, if you're surprised by the presence of patriarchalism in a 1950s movie, it's because you are not paying even a tiny bit of attention) is the film's outdated racial depiction: it's not for very long, but Bend of the River actually sees fit to haul out Stepin Fetchit, the most notorious of all professional embodiments of the ugliest stereotype of the cringing, lazy black man, after that actor had been out of commission for well over a decade, as far as features for a white target audience went. And sure enough, he slinks, and warbles nervously, and chomps all over English in the most servile, scraping way, and it's so completely unnecessary to film in any way - the scenes in which he appear are literally just there to add, I beg you to pardon the expression, some local color - that it's far more uncomfortable than most garden variety '50s movie racism.

I don't know how to walk back from that, so I won't bother trying, and shall instead just bodily wrench the review back on track: though it is the most flawed and maybe the least interesting of the Mann/Stewart Westerns, Bend of the River is still great, cunningly and gorgeously made, and impressively unyielding in its physical brutality. It lingers intently on its characters, with cinematographer Irving Glassberg always favoring shots that emphasise the humans, either in relationship to each other or to the wilderness that constantly looms as a promise and a threat. For all its glorious Technicolor tourism of the Cascades, the movie never favors sweeping vistas and spectacular landscape photography: wide shots always serve a strictly narrative function. And the most important thing the mountains ever do is to contrast with the people, never show off their rocky grandeur.

Its preference for psychology over all other concerns puts Bend of the River in the early wave of a new kind of genre filmmaking: maybe most prominent in the Westerns, given how dramatic the discrepancy between the most and least sophisticated examples of the form, though it's certainly visible in the evolution of film noir and the gradual development of science fiction from idiot nonsense to social commentary. In the dawning years of the Cold War, the American Empire, the Post-War World, whatever the hell you want to call it, cinema as a whole began to grow very obsessed with the inner workings of the mind; I am no sociologist and cannot say what this says about the changes in society beyond its art. But it's as real as anything, that movies began to grapple with psychological interiors like never before. It's always easiest (and I tend to think, most rewarding) to see those kinds of shifts in the most innocuous pulp; Bend of the River is so accomplished that we might not want to use a word like "pulp" to describe it, but it still fits, and it showcases the need to acknowledge difficulties with individuals and societies in a deep, probing way, right at the start of the period in American history that's generally considered to have been more anxious to paper over those difficulties than any before or since. There's something really special to me about movies whose lessons and art are timeless, but whose interests and obsessions are particularly attached to a single, specific context; Mann's Westerns are both agelessly classic and irrevocably dated to the '50s in just that way, and they're able to do double-duty as time capsule and top-notch entertainment alike. Even when it's not perfect, it doesn't get much more rewarding than that.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1952

-United Artists releases Bwana Devil, igniting the first 3-D craze, while This Is Cinerama introduces the most gimmicky possible version of widescreen

-John Ford makes Ireland look even lovelier in the romantic comedy The Quiet Man

-The year's biggest hit, and the Best Picture Oscar winner, is Cecil B. DeMille's peculiarly unwatchable circus drama The Greatest Show on Earth

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1952

-Mizoguchi Kenji's magnificent feminist period drama Life of Oharu is released in Japan

-After making movies throughout Europe, Brazilian director Alberto Cavalcanti makes his first works back at home, Song of the Sea and Simon the One-Eyed

-Future Italian master Federico Fellini's makes his solo directorial debut, The White Sheik