Blockbuster history: Sci-fi comics

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the most outlandish movie yet made by the Marvel film factory, Guardians of the Galaxy, at least wins points for feeling unlike all the other comic book adaptations of recent vintage, looking back to the sci-fi adventures of the '80s. And at least one of those, I am happy to say, was also adapted from graphic literature.

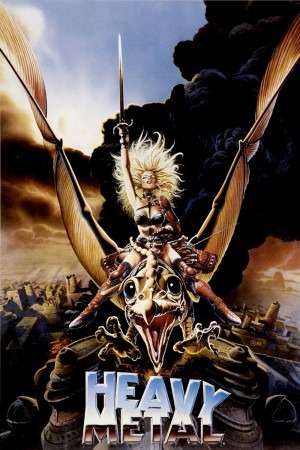

In principle, I adore 1981's Heavy Metal. It represents a kind of science-fiction storytelling inordinately rare in English-language filmmaking, on the model of the anything goes kind of batshit nuts world-creating that went in in things like Weird Tales and Amazing Stories back in their early years; its multiple visual styles are all taken from the pages its namesake magazine, which nurtured some incredibly gifted talents in both comic book art and writing. And it's an animated movie from Canada, which is pretty much all it takes to get me interested.

The downside to being based on Heavy Metal, though, is that the film is, well, based on Heavy Metal: a publication that exemplifies the notion that the euphemism "adult material" almost exclusively denotes content which is chiefly of appeal to people other than adults. 12-year-old boys, to take the age group usually picked in such conversations, and I'm sure that in history there have been many 12-year-old boys of class, refinement, and unusual moral and aesthetic sensitivity. But Heavy Metal doesn't care about them. It is a title premised on the wholly sound observation that you can get a 12-year-old boy to pay any price for a glimpse of tits; even cartoon tits, like the ones here. A little gore here, a little astonishing creation of disparate worlds from across the galaxy there; but mostly it is a film dedicated so making sure that there is as much footage possible of rosy areolae surrounding lovingly drafted erect nipples on breasts the size of volleyballs. It is a film that can imagine planet-spanning conquests between toxic zombies on giant bats fighting spirit warriors from a dead race on a huge pterodactyl, but it can't quite fathom a universe where any of the women wear shirts.

I concede that calling this a "downside" ignores the fact that for Heavy Metal's target audience, it's actually closer to being exactly the point of the thing, and while it's easy to ask a heterosexual adolescent boy, "don't you want more from your art than the constant sexual objectification of physiologically impossible women?", there's no point in being distressed when he answers "no". So on we go to the other really big, heaving problem with Heavy Metal, which is that it's an anthology film: the whole shebang is directed by Gerald Potterton with a screenplay by Daniel Goldberg & Len Blum, which gives it a certain consistency of tone, but it was adapted from stories by a number of different people, and even animated by several different studios. It's just the nature of anthology films, that they are never consistent: some segments are brilliant, some work intermittently, some completely suck. That's the nature of the animal. And Heavy Metal compounds things by wrapping all of its individual stories in a completely perplexing and ineffectual frame narrative in which a glowing green orb from space called the Loc-Nar (Percy Rodriguez) melts an astronaut and torments his daughter by promising her that it is the embodiment of all evil in the universe. And before it does whatever heinous crimes to her that it has in mind, it's going to show her a bunch of its greatest hits, conveniently demonstrating a whole range of the kind of evil that it can engender, in all sorts of varied environments. It's as nonsensical as the moment in The Star Wars Holiday Special where a galaxy-wide red alert demands that we learn something about the corruption of the Rebellion by watching Bea Arthur play a singing bartender. Also, the way that the girl spends the entire frame, interstitials an all, with a single look of aghast terror plastered on her face is wildly out of proportion to the Loc-Nar's rather wandering, businesslike way of presenting its flashbacks.

The worst of the framing narrative doesn't occur until its second or third appearance, though; and happily, the frame is easily the worst individual component of the movie. The only individual story that even comes close to the same low level is "So Beautiful and So Dangerous", based on an Angus McKie story, which depicts a Pentagon secretary (Alice Playten) being abducted to a spaceship by an alien android (Roger Bumpass), at which time she strikes up a sexual affair with a robot voiced by John Candy. The ship's pilots (Harold Ramis and Eugene Levy) are bored and get high, driving the ship into the flight deck of a space station. What in the living hell this has to do with the Loc-Nar's ancient cosmic evil is anybody's guess, and the aimless, dimwitted comedy on display is hardly captivating enough to sell the short on its own merits, particularly coupled with its complete abandonment of its own plot midway through, when it shifts from "abducted women reaches sexual ecstasy with a vibrating robot" to "stoner gags with aliens".

Everything else is at least satisfactory, though the best of the segments by far, "B-17", gets that way by abandoning science fiction for horror (it's adapted from a Dan O'Bannon story, no less), and as such implicitly calls the whole idea of the project into question a bit. It's your basic "alien orb turns dead airmen into skeletal zombies in a bomber during World War II" number, and the undead are rendered with particularly loving care by the animation team on that segment. It's heavy on atmosphere and abruptly short on plot: just creating a mood and getting the hell out of there, and in that respect it's kind of cheating: most of the other segments are at least partially involved in world-building and completely removed from the simpler goals of horror, so it's harder for them to achieve as much without having to work a lot harder for it. But there are other standouts; "Harry Canyon," the first after the framing narrative is established, is probably my favorite of these, a straightforward future-noir piece that's one of the original stories Goldberg & Blum whipped up just for the movie. The crude art style with heavy lines and an exaggerated impulse to realism that defines most, but not quite all of the segments is better suited to the story here than anywhere else; and the narrative is clearer on its own terms than anything else.

The other three segments include the Richard Corben story "Den", a hyper-sexualised "weird fantasy" world story that feels influenced by the work of Lord Dunsany (or rather, one of the countless works influenced by Lord Dunsany throughout the 20th Century), and involving possibly the least appealing animation of all of them; and the Bernie Wrightson story "Captain Sternn", an odd comic bit that has no real ending, nor a beginning. The film's showpiece is the other Goldberg & Blum original, "Taarna", which takes place on a world overrun by toxic mutant barbarians, and involves a woman wearing straps of cloth across her nipples and vagina who speaks no words and swings a big sword, which she acquires in a sequence that I am absolutely certain must have influenced He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, that most beloved of all toy commercials in the guise of a TV cartoon. And indeed, the whole of the segment seems to suggest quite a lot of influence, on that series and anything else you can name where a desert planet with modular buildings is inhabited by sci-fi barbarians: the design is pretty terrific, I will happily concede that. So is the effects animation, including some flying shots that must have absolutely pushed the maximum limit that the budget of a Canadian animated feature could mange in 1981. The story is a confusing, undernourished wreck (uniquely among the segments, it feels like it could only be better with more running time to explore its world and define its rules, and to create more of a personality for its blank protagonist), but it looks nice.

Underneath all of this, we hear plenty of songs that are either heavy metal, or comfortably near to it, or don't come even close but are present anyway (has anyone, in history, tried to argue that Devo was a heavy metal group?). Mostly, the soundtrack feels like somebody wanted to justify the title of the feature, and not that anybody had a driving passion for metal that led them to make cunning and artistically inevitable marriages of music and image, though there's never anything that really feels wrong, just mostly arbitrary. That's largely how the film as a whole feels, too: a bit of inspiration but not enough to support the whole 90-minute running time, and too many of the stories end with a fizzled "so that happened" feeling, rather than the punch that comes from a really good short story collection. It's one of the more unusual corners of the early-'80s "Let's be Star Wars" cottage industry, but not also one of the most effective; and outside of animation buffs, metal historians, and the horny 12-year-old boy who lives in the heart of all of us, there's just not that much reason to bother with it.

In principle, I adore 1981's Heavy Metal. It represents a kind of science-fiction storytelling inordinately rare in English-language filmmaking, on the model of the anything goes kind of batshit nuts world-creating that went in in things like Weird Tales and Amazing Stories back in their early years; its multiple visual styles are all taken from the pages its namesake magazine, which nurtured some incredibly gifted talents in both comic book art and writing. And it's an animated movie from Canada, which is pretty much all it takes to get me interested.

The downside to being based on Heavy Metal, though, is that the film is, well, based on Heavy Metal: a publication that exemplifies the notion that the euphemism "adult material" almost exclusively denotes content which is chiefly of appeal to people other than adults. 12-year-old boys, to take the age group usually picked in such conversations, and I'm sure that in history there have been many 12-year-old boys of class, refinement, and unusual moral and aesthetic sensitivity. But Heavy Metal doesn't care about them. It is a title premised on the wholly sound observation that you can get a 12-year-old boy to pay any price for a glimpse of tits; even cartoon tits, like the ones here. A little gore here, a little astonishing creation of disparate worlds from across the galaxy there; but mostly it is a film dedicated so making sure that there is as much footage possible of rosy areolae surrounding lovingly drafted erect nipples on breasts the size of volleyballs. It is a film that can imagine planet-spanning conquests between toxic zombies on giant bats fighting spirit warriors from a dead race on a huge pterodactyl, but it can't quite fathom a universe where any of the women wear shirts.

I concede that calling this a "downside" ignores the fact that for Heavy Metal's target audience, it's actually closer to being exactly the point of the thing, and while it's easy to ask a heterosexual adolescent boy, "don't you want more from your art than the constant sexual objectification of physiologically impossible women?", there's no point in being distressed when he answers "no". So on we go to the other really big, heaving problem with Heavy Metal, which is that it's an anthology film: the whole shebang is directed by Gerald Potterton with a screenplay by Daniel Goldberg & Len Blum, which gives it a certain consistency of tone, but it was adapted from stories by a number of different people, and even animated by several different studios. It's just the nature of anthology films, that they are never consistent: some segments are brilliant, some work intermittently, some completely suck. That's the nature of the animal. And Heavy Metal compounds things by wrapping all of its individual stories in a completely perplexing and ineffectual frame narrative in which a glowing green orb from space called the Loc-Nar (Percy Rodriguez) melts an astronaut and torments his daughter by promising her that it is the embodiment of all evil in the universe. And before it does whatever heinous crimes to her that it has in mind, it's going to show her a bunch of its greatest hits, conveniently demonstrating a whole range of the kind of evil that it can engender, in all sorts of varied environments. It's as nonsensical as the moment in The Star Wars Holiday Special where a galaxy-wide red alert demands that we learn something about the corruption of the Rebellion by watching Bea Arthur play a singing bartender. Also, the way that the girl spends the entire frame, interstitials an all, with a single look of aghast terror plastered on her face is wildly out of proportion to the Loc-Nar's rather wandering, businesslike way of presenting its flashbacks.

The worst of the framing narrative doesn't occur until its second or third appearance, though; and happily, the frame is easily the worst individual component of the movie. The only individual story that even comes close to the same low level is "So Beautiful and So Dangerous", based on an Angus McKie story, which depicts a Pentagon secretary (Alice Playten) being abducted to a spaceship by an alien android (Roger Bumpass), at which time she strikes up a sexual affair with a robot voiced by John Candy. The ship's pilots (Harold Ramis and Eugene Levy) are bored and get high, driving the ship into the flight deck of a space station. What in the living hell this has to do with the Loc-Nar's ancient cosmic evil is anybody's guess, and the aimless, dimwitted comedy on display is hardly captivating enough to sell the short on its own merits, particularly coupled with its complete abandonment of its own plot midway through, when it shifts from "abducted women reaches sexual ecstasy with a vibrating robot" to "stoner gags with aliens".

Everything else is at least satisfactory, though the best of the segments by far, "B-17", gets that way by abandoning science fiction for horror (it's adapted from a Dan O'Bannon story, no less), and as such implicitly calls the whole idea of the project into question a bit. It's your basic "alien orb turns dead airmen into skeletal zombies in a bomber during World War II" number, and the undead are rendered with particularly loving care by the animation team on that segment. It's heavy on atmosphere and abruptly short on plot: just creating a mood and getting the hell out of there, and in that respect it's kind of cheating: most of the other segments are at least partially involved in world-building and completely removed from the simpler goals of horror, so it's harder for them to achieve as much without having to work a lot harder for it. But there are other standouts; "Harry Canyon," the first after the framing narrative is established, is probably my favorite of these, a straightforward future-noir piece that's one of the original stories Goldberg & Blum whipped up just for the movie. The crude art style with heavy lines and an exaggerated impulse to realism that defines most, but not quite all of the segments is better suited to the story here than anywhere else; and the narrative is clearer on its own terms than anything else.

The other three segments include the Richard Corben story "Den", a hyper-sexualised "weird fantasy" world story that feels influenced by the work of Lord Dunsany (or rather, one of the countless works influenced by Lord Dunsany throughout the 20th Century), and involving possibly the least appealing animation of all of them; and the Bernie Wrightson story "Captain Sternn", an odd comic bit that has no real ending, nor a beginning. The film's showpiece is the other Goldberg & Blum original, "Taarna", which takes place on a world overrun by toxic mutant barbarians, and involves a woman wearing straps of cloth across her nipples and vagina who speaks no words and swings a big sword, which she acquires in a sequence that I am absolutely certain must have influenced He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, that most beloved of all toy commercials in the guise of a TV cartoon. And indeed, the whole of the segment seems to suggest quite a lot of influence, on that series and anything else you can name where a desert planet with modular buildings is inhabited by sci-fi barbarians: the design is pretty terrific, I will happily concede that. So is the effects animation, including some flying shots that must have absolutely pushed the maximum limit that the budget of a Canadian animated feature could mange in 1981. The story is a confusing, undernourished wreck (uniquely among the segments, it feels like it could only be better with more running time to explore its world and define its rules, and to create more of a personality for its blank protagonist), but it looks nice.

Underneath all of this, we hear plenty of songs that are either heavy metal, or comfortably near to it, or don't come even close but are present anyway (has anyone, in history, tried to argue that Devo was a heavy metal group?). Mostly, the soundtrack feels like somebody wanted to justify the title of the feature, and not that anybody had a driving passion for metal that led them to make cunning and artistically inevitable marriages of music and image, though there's never anything that really feels wrong, just mostly arbitrary. That's largely how the film as a whole feels, too: a bit of inspiration but not enough to support the whole 90-minute running time, and too many of the stories end with a fizzled "so that happened" feeling, rather than the punch that comes from a really good short story collection. It's one of the more unusual corners of the early-'80s "Let's be Star Wars" cottage industry, but not also one of the most effective; and outside of animation buffs, metal historians, and the horny 12-year-old boy who lives in the heart of all of us, there's just not that much reason to bother with it.