Modern welfare

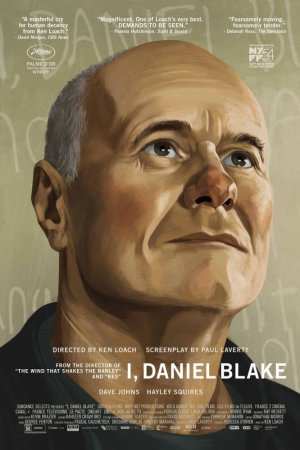

It's tempting to write off I, Daniel Blake as just Ken Loach doing that Ken Loach that he does so well, as if being one the greatest leftist message-movie directors in the history of the English language cinema is something to sniff at. Certainly it's more than tempting to look at the uniquely great main competition at the 2016 Cannes International Film Festival and wonder what in the name of our sweet lord Jesus the jury thought this film had that Toni Erdmann or The Handmaiden didn't, when they handed it the Palme d'Or

But that is a small-minded way to go about the business of being a movie-watcher, particularly in the face of such a committed, passionate, desperately urgent film as I, Daniel Blake, which is certainly a hectoring political op-ed about The State Of Britain Today, but when you've been hectored by Loach, you've been hectored by the very best.

The title character is a 59-year-old carpenter (played by stand-up comedian Dave Johns) who has, in the immediate backstory of the film, suffered a minor heart attack. He's been receiving good treatment from a never-seen cardiologist, with the admonishment that he must take some time off work to allow his body to fully recover. And so he applies for the Employment and Support Allowance, a social welfare program that will provide him with enough money to live on until his doctor gives him the go-ahead to start seeking work again. The problem creeps in when it turns out that one person who needed to fill out one form somewhere back along the line didn't do so, and therefore Daniel can't receive support until after he goes through a lengthy, arbitrary appeal that almost certainly will go against him. In the meantime, he can only receive a Jobseeker's Allowance, which requires that he prove that he's actively looking for work, despite being flatly told that looking for work is going to put his health at risk. Adding to the general misery, almost all of the UK's social programs have transitioned to internet-only application forms, and Daniel does not own a computer and knows nothing at all about how they work.

Paul Laverty's screenplay (marking his 20th year as a regular Loach collaborator) draws unapologetically from Kafka's The Trial, in sketching out a nightmare world of bureaucracy where every problem has a solution that is itself an even more daunting problem. Only instead of Kafka's shadowy world of allegory, I, Daniel Blake takes place right out in the sunshine of Real-World Great Britain, and has been shot in the traditionally unadorned Ken Loach style, his inheritance from the kitchen sink realism of the '50s and '60s where his career took off. The movie isn't indifferent to visuals: not with the terrific cinematographer Robbie Ryan involved. If nothing else, the film's cunning, calculated use of unconventional focal depth to ask us to focus on the people in the background, the people who aren't in the center of the story, is tremendously interesting, a most democratic & egalitarian aesthetic for an egalitarian story. But there's nothing stylish about the movie. One gets the sense that all concerned would consider that a way of trivializing the very serious message of it all, and they'd be right, of course.

No indeed, this is very much a message film, presenting a perfectly nice, mostly unexceptional man who through no fault of his own can't figure out how in the hell to navigate Britain's morass of social welfare programs that are apparently designed with the single intention of preventing people from receiving social welfare. It is a vigorously left-wing affair, presenting Daniel's increasing despair as a profoundly normal, every day tragedy, and demanding that we grow good and angry about it. To compound matters, there's another story about normal, decent people being pulverised because of a solitary "whoops" running in tandem with Daniel's: Katie (Hayley Squires), a single mother who has just relocated from London to Newcastle because that's where the government housing agency shunted her, and whose unfamiliarity with the new city led to her being a few minutes late for a meeting on the first day. And because of those few minutes, she's been punished with severe reductions to her benefits. So Daniel and Katie form a bond, one that is happily quite without even the smallest romantic overtones, as they try to help each other survive.

Loach and Laverty don't hold back in piling up the misery, and I can't honestly say that the movie's better off for it: the developments of Katie's plotline, for one thing, are as unsurprising as they are trite. Delicacy around spoilers leads me to avoid saying more, but- oh for fuck's sake. She becomes a prostitute. It's Poverty Is Hell 101 stuff, though thankfully not dwelt upon too very much. And anyway, Squires's performance is so excellent that it largely carries us past the worst bits. The same is true for Johns, whose entire role is an exercise in internalised frustration bursting out in helpless rages, growing increasingly desperate and teary and angry as the plot clatters away without any form of resolution or satisfaction on the horizon. His background in comedy turns out to be the film's secret weapon par excellence: he plays the role with the beat-beat-punchline timing of a comic, which in the context of a stern and mirthless examination of impoverishment proves to be a remarkably effective way of grounding the film's suffocating tragedy in quicksilver human feeling. I'd still give Squires best-in-show accolades, if only for the gutting honesty of how she plays one key scene at a foodbank - itself a tiny jewel of activist filmmaking, among the most potent depictions of the demhumanising viciousness of poverty I've ever seen in a movie. But the both of them together are a perfectly matched set, putting a tangible, personal face on the impersonality of stats and figures about welfare programs.

The film is a polemic, and that does mean some artistry is sacrificed: the final scene is nothing but an over-written, anti-dramatic monologue neatly summing up the film's arguments about human dignity in the face of immiseration, and while I admire the sentiment, it's the opposite of cinema. But it is a polemic in favor of beliefs I happen to agree with entirely - that it is better for governments to alleviate economic suffering than to cause it. I'm not at all confident that's enough to justify giving I, Daniel Blake the world's most prestigious film award, but it's certainly gratifying that the film exists in such a visible way.

But that is a small-minded way to go about the business of being a movie-watcher, particularly in the face of such a committed, passionate, desperately urgent film as I, Daniel Blake, which is certainly a hectoring political op-ed about The State Of Britain Today, but when you've been hectored by Loach, you've been hectored by the very best.

The title character is a 59-year-old carpenter (played by stand-up comedian Dave Johns) who has, in the immediate backstory of the film, suffered a minor heart attack. He's been receiving good treatment from a never-seen cardiologist, with the admonishment that he must take some time off work to allow his body to fully recover. And so he applies for the Employment and Support Allowance, a social welfare program that will provide him with enough money to live on until his doctor gives him the go-ahead to start seeking work again. The problem creeps in when it turns out that one person who needed to fill out one form somewhere back along the line didn't do so, and therefore Daniel can't receive support until after he goes through a lengthy, arbitrary appeal that almost certainly will go against him. In the meantime, he can only receive a Jobseeker's Allowance, which requires that he prove that he's actively looking for work, despite being flatly told that looking for work is going to put his health at risk. Adding to the general misery, almost all of the UK's social programs have transitioned to internet-only application forms, and Daniel does not own a computer and knows nothing at all about how they work.

Paul Laverty's screenplay (marking his 20th year as a regular Loach collaborator) draws unapologetically from Kafka's The Trial, in sketching out a nightmare world of bureaucracy where every problem has a solution that is itself an even more daunting problem. Only instead of Kafka's shadowy world of allegory, I, Daniel Blake takes place right out in the sunshine of Real-World Great Britain, and has been shot in the traditionally unadorned Ken Loach style, his inheritance from the kitchen sink realism of the '50s and '60s where his career took off. The movie isn't indifferent to visuals: not with the terrific cinematographer Robbie Ryan involved. If nothing else, the film's cunning, calculated use of unconventional focal depth to ask us to focus on the people in the background, the people who aren't in the center of the story, is tremendously interesting, a most democratic & egalitarian aesthetic for an egalitarian story. But there's nothing stylish about the movie. One gets the sense that all concerned would consider that a way of trivializing the very serious message of it all, and they'd be right, of course.

No indeed, this is very much a message film, presenting a perfectly nice, mostly unexceptional man who through no fault of his own can't figure out how in the hell to navigate Britain's morass of social welfare programs that are apparently designed with the single intention of preventing people from receiving social welfare. It is a vigorously left-wing affair, presenting Daniel's increasing despair as a profoundly normal, every day tragedy, and demanding that we grow good and angry about it. To compound matters, there's another story about normal, decent people being pulverised because of a solitary "whoops" running in tandem with Daniel's: Katie (Hayley Squires), a single mother who has just relocated from London to Newcastle because that's where the government housing agency shunted her, and whose unfamiliarity with the new city led to her being a few minutes late for a meeting on the first day. And because of those few minutes, she's been punished with severe reductions to her benefits. So Daniel and Katie form a bond, one that is happily quite without even the smallest romantic overtones, as they try to help each other survive.

Loach and Laverty don't hold back in piling up the misery, and I can't honestly say that the movie's better off for it: the developments of Katie's plotline, for one thing, are as unsurprising as they are trite. Delicacy around spoilers leads me to avoid saying more, but- oh for fuck's sake. She becomes a prostitute. It's Poverty Is Hell 101 stuff, though thankfully not dwelt upon too very much. And anyway, Squires's performance is so excellent that it largely carries us past the worst bits. The same is true for Johns, whose entire role is an exercise in internalised frustration bursting out in helpless rages, growing increasingly desperate and teary and angry as the plot clatters away without any form of resolution or satisfaction on the horizon. His background in comedy turns out to be the film's secret weapon par excellence: he plays the role with the beat-beat-punchline timing of a comic, which in the context of a stern and mirthless examination of impoverishment proves to be a remarkably effective way of grounding the film's suffocating tragedy in quicksilver human feeling. I'd still give Squires best-in-show accolades, if only for the gutting honesty of how she plays one key scene at a foodbank - itself a tiny jewel of activist filmmaking, among the most potent depictions of the demhumanising viciousness of poverty I've ever seen in a movie. But the both of them together are a perfectly matched set, putting a tangible, personal face on the impersonality of stats and figures about welfare programs.

The film is a polemic, and that does mean some artistry is sacrificed: the final scene is nothing but an over-written, anti-dramatic monologue neatly summing up the film's arguments about human dignity in the face of immiseration, and while I admire the sentiment, it's the opposite of cinema. But it is a polemic in favor of beliefs I happen to agree with entirely - that it is better for governments to alleviate economic suffering than to cause it. I'm not at all confident that's enough to justify giving I, Daniel Blake the world's most prestigious film award, but it's certainly gratifying that the film exists in such a visible way.