Hollywood Century, 1983: In which the New Hollywood kids, reeling from the unexpected arrival of the 1980s, pay for their alleged sins

Whatever sequence of events, marketing pressures, shifting audiences preferences, and directorial indulgences contributed to the death of the New Hollywood Cinema at the dawn of the 1980s, it's satisfyingly easy to point out when the corpse stopped twitching. In February, 1982, New Hollywood idol and godfather, if you will (and if you won't, it's no more than I deserve) Francis Ford Coppola released what is almost incontestably the most ill-advised, jaw-dropping insular, willfully alienating and implausible film made by any of his generation of filmmakers after their respective rises to prominence, the glowingly colored Las Vegas drama about a collapsing marriage, One from the Heart. I will contentedly declare that I enjoy, sort of, and admire, in a way, this fucked-up little geyser of Coppola's most weirdly personal aesthetic fascinations; but holy crap, there's just no way it should exist.

The film was conceived as the pilot, essentially for Coppola's passion project, American Zoetrope Studios. Tucked away in Los Angeles, right underneath the major studios' noses, Coppola hoped to make a haven for the creative, visionary filmmakers who'd suddenly found the ground shifting under their feet. Looking to make a quick, cheap film to get American Zoetrope's feet solidly underneath it, Coppola's simply little domestic musical quickly exploded from a $2 million quickie to a $27 million monster of fussy sets and sniper-precise manipulation of objects and actors within those sets, of startling, gorgeous colors, of Tom Waits and Crystal Gayle glumly wail about the basic disconnect between humans as set out in the vivid and grotesque imagery of Waits's lyrics for the wall-to-wall songs. Instead of declaring American Zoetrope open for business, One from the Heart shot it point-blank in the forehead: as could be predicted by pretty much every human being who watched the film besides Coppola himself, One from the Heart was an enormous flop, earning less than $700,000 in its humiliating U.S. theatrical run, and plunging Coppola - whose personal fortune had formed the backbone of the film and American Zoetrope's financial portfolio - into crushing debt.

This is not, however, a review of One from the Heart.

After the positively murderous failure of his grand folly, Coppola - an Oscar-winning filmmaker who went 4-for-4 in the 1970s in directing movies that would be almost instantaneously regarded as essential modern masterpieces - found himself plunged straight into Director Jail. I am not sure when to say he was released; I am not honestly sure that he ever was released, unless we assume that cobbling together defiantly oddball little curios like Youth Without Youth on European shoestring budgets represents the obvious career path for the man behind The Godfather.

Coppola was obliged to become a singularly financially-driven filmmaker in short order - exactly the opposite of what the American Zoetrope experiment was hoping for. But becoming a commercial sell-out does not necessarily require one to forget all about how to make movies, and it is very much the case that most of Coppola's blatantly pandering cash-grabs are also, to some degree, concerned with artistry and creativity as well, they just have to hide it a little. And this brings us to the very first of those cash-grabs, 1983's The Outsiders, something that we'd now call a YA adaptation (the screenplay was by Kathleen Rowell, the first she ever saw produced), but at the time of its creation was simply an example of a filmmaker discovering, somewhat by accident, that here was a property which would almost certainly make a nice chunk of money and also provide a crutch for him to do interesting things that had very little to do with the actual task of adapting S.E. Hinton's 1967 novel (published when she was just 18!), which came to his attention when a Fresno, CA middle school class voted him the filmmaker they most wanted to see tackle the book that was held in dear esteem by all of them. A fun exercise is to glance over Coppola's filmography to that point, take out all the titles that are spectacularly inappropriate for middle-schoolers, and determine that the class apparently rallied behind Coppola on the strength of his 1968 adaptation of Finian's Rainbow, every kid's favorite musical.

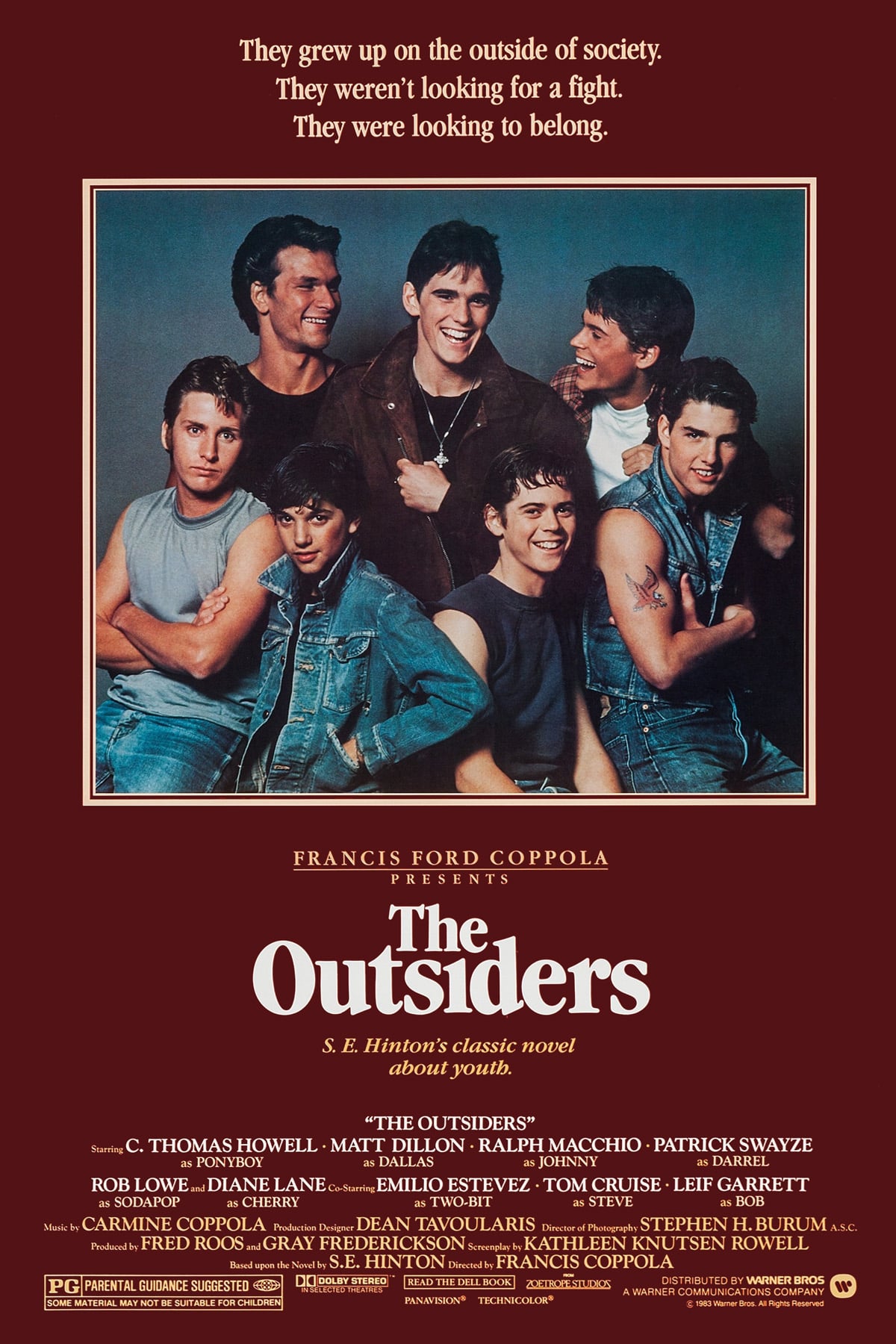

The Outsiders - about which I know nothing at all save that it is the basis for this film, and my apologies to its apparently strong, multi-generational audience of passionate followers for my ignorance - is a pretty basic JD story set in a vaguely defined Oklahoma in a vaguely specified 1960s. It takes place in a small town where teen culture is apparently divided between two gangs: the lower-glass Greasers, and the rich Socs. Our main points of entry in to this world are the two youngest, least-qualified members of the Greasers: 14-year-olds Ponyboy Curtis (C. Thomas Howell) and Johnny Cade (Ralph Macchio). They are chiefly in thrall to Dallas Winston (Matt Dillon), the sort of low-key cad who reads as "charismatic" almost exclusively to younger, impressionable males, but for Ponyboy, at least, the Greasers are a family tradition: among its members are his elder brothers Sodapop (Rob Lowe) and Darrel (Patrick Swayze), who seems to be the oldest and most leaderly of the gang. The boys end up accidentally killing one of the Socs, and go into hiding under the dubious guidance of Dallas; during their exile in the wilds of the Plain states, they manage to heroically and selflessly save some children from a burning church, and return home, to find that heroism hasn't quite wiped the legal slate clean, and also the Socs are plotting a rumble to get back at the Greasers.

Straightforward enough (and about a quarter shorter than the "full" version Coppola presented to Warner Bros., which apparently kept more of the resonance of the book intact - it has since been released to DVD), but there's absolutely no sense at any point that The Outsiders is to any meaningful extent a story of life among the gangs, no matter how much it keeps tapping you on the shoulder to ask, "By the way, did you say something about West Side Story? No, huh? I could have sworn you did. What about Rebel Without a Cause?" It is, instead, an attempt to capture penetrating, iconic imagery of the American West in a way that reflects the particular soulfulness and questioning of these young, tragically dislocated hoodlums. More specifically, it's an overt nod to Gone with the Wind, which is specifically mentioned at multiple points in the dialogue and obviously referenced, especially in the middle of the film, in sequences that crib from that film's famous "silhouettes against an orange-red sky" motif.

It's unapologetic Romanticism, in a film that looks at its teenage characters, with their overheated passions and intense feelings; and then looks at its prospective teenage audience, with its proprietary, emotionally invested ownership of the book; and then decides "well, let's go ahead and be sincere about all this, then". Which is kind of refreshing and bold: a movie about heightened teen melodrama that firmly embraces that melodrama with both arms, trying to find cinematic equivalences to to the heady, potent certitude that this feeling we are feeling is the absolute most important thing ever. The Outsiders is gorgeous, shamelessly so: Coppola and cinematographer Stephen H. Burum invest heavily in draping the perfectly attractive scrublands of Oklahoma, the picture-postcard nostalgic locations, and the slightly-too-clean but soft and peaceable interiors, in dappled lighting and slow movements, and Coppola and editor Anne Goursaud then combine those images in emotionally intuitive rather than narratively driven cuts. Unexpectedly, it turns out to be something like Malick's Badlands for '80s teen audiences (this is, again, most true of the film's middle, which I find to be easily its most compelling sequence: the beginning is over-invested in period signifiers that don't really matter, the end suddenly starts to double down on the plot and climaxes in an impressionistically lovely, but otherwise imprecise gang rumble), right down to the way that the dusky dryness of the setting is both enormously specific in every detail of every building, while also feeling like a dream-soaked Neverland. The textures and sounds of the physical setting are enormously important, that is, while the notion of Oklahoma, 1965, is almost completely besides the point.

Coppola and company do an outstanding job of creating and sustaining a mood through their visuals, and occasional shifts into Expressionism (Ponyboy, recalling his parents' death, has a car apparently drive over his face during a dissolve, with a cut to that car wrecking in a visually and audibly garish shift that's almost funny in its shocking violence), making a film about the idea of being an isolated teenager trying to find love, family, and a place as a series of dense and empty images, with Coppola's father Carmine providing an absolutely terrific score that unsentimentally provides a sense of placelessness, and Howell, excellent in only his second credited film role, seems to absorb all the internal confusion, yearning need, fearful self-doubt, and anger of every movie about juvenile delinquents ever and turn them into an excellent vessel for the film's concepts.

What I'm not as convinced about is that Coppola and company do as good a job, or even a good job, period, at telling the basic story of characters that Hinton set out. In between all the deliberately, self-consciously iconic imagery, the character moments feel a little straightforward and disinvested, and though the film is impressively stocked with young people who would go on to have important and highly visible careers - besides Howell, Dillon, Macchio, Swayze, and Lowe, Diane Lane has a big role, and Tom Cruise and Emilio Estevez both show up - Coppola only really seems to take an interest in Howell, and Macchio and Dillon as the people Howell interacts with the most, leaving the rest of the cast as attractive faces to fill out the frame with business that seems more about creating a sense of movement than doing anything to build character or stress the reality of the world being depicted. And Howell himself is, as I said, more effective at channeling concepts than really clarifying who Ponyboy is: in fact, The Outsiders in this form is largely predicated on Ponyboy not being anyone specific, but being an abstracted concept about "being a lonely teenager". The result is that The Outsiders works entirely as an explication of a mindset rather than as a depiction of individual minds, and while its target audience has, apparently, found this gratifying and legitimising for some 30 years now, the film strikes me as being stubbornly remote, for all its undeniable beauty and talent.

It made its money, anyway: no blockbuster, but enough to ease Coppola back from the nightmare of One from the Heart-induced destitution. It's such a perfect metaphor for '70s cinema transitioning to '80s cinema that I'm almost embarrassed to make it the punchline of a whole review: the artistic madman, tamed and docile, but still making movies he at least can believe in, and all to give the audience exactly what it was asking for and nothing more. It's a lovely film in a lot of ways, for all that it's a little too safe, and it's at any rate a more satisfying example of the artist-as-talented-hack exercise than The Godfather, Part III would prove to be, for starters.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1983

-Moms watching their daughters die of cancer prove shockingly popular in Terms of Endearment

-Tom Cruise in his underwear is popular, but it's not really shocking, in Risky Business

-A Christmas Story is not especially popular at first, but over the years, this will change

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1983

-It's Bond vs. Bond, as the "official" movie Octopussy, starring Roger Moore, outperforms the return of Sean Connery to his most iconic role in Never Say Never Again

-Robert Bresson ends his career with the pseudo-Marxist thriller L'argent

-Bizarre Japanese filmmaker Oshima Nagisa and bizarre British pop star David Bowie collaborate in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence

The film was conceived as the pilot, essentially for Coppola's passion project, American Zoetrope Studios. Tucked away in Los Angeles, right underneath the major studios' noses, Coppola hoped to make a haven for the creative, visionary filmmakers who'd suddenly found the ground shifting under their feet. Looking to make a quick, cheap film to get American Zoetrope's feet solidly underneath it, Coppola's simply little domestic musical quickly exploded from a $2 million quickie to a $27 million monster of fussy sets and sniper-precise manipulation of objects and actors within those sets, of startling, gorgeous colors, of Tom Waits and Crystal Gayle glumly wail about the basic disconnect between humans as set out in the vivid and grotesque imagery of Waits's lyrics for the wall-to-wall songs. Instead of declaring American Zoetrope open for business, One from the Heart shot it point-blank in the forehead: as could be predicted by pretty much every human being who watched the film besides Coppola himself, One from the Heart was an enormous flop, earning less than $700,000 in its humiliating U.S. theatrical run, and plunging Coppola - whose personal fortune had formed the backbone of the film and American Zoetrope's financial portfolio - into crushing debt.

This is not, however, a review of One from the Heart.

After the positively murderous failure of his grand folly, Coppola - an Oscar-winning filmmaker who went 4-for-4 in the 1970s in directing movies that would be almost instantaneously regarded as essential modern masterpieces - found himself plunged straight into Director Jail. I am not sure when to say he was released; I am not honestly sure that he ever was released, unless we assume that cobbling together defiantly oddball little curios like Youth Without Youth on European shoestring budgets represents the obvious career path for the man behind The Godfather.

Coppola was obliged to become a singularly financially-driven filmmaker in short order - exactly the opposite of what the American Zoetrope experiment was hoping for. But becoming a commercial sell-out does not necessarily require one to forget all about how to make movies, and it is very much the case that most of Coppola's blatantly pandering cash-grabs are also, to some degree, concerned with artistry and creativity as well, they just have to hide it a little. And this brings us to the very first of those cash-grabs, 1983's The Outsiders, something that we'd now call a YA adaptation (the screenplay was by Kathleen Rowell, the first she ever saw produced), but at the time of its creation was simply an example of a filmmaker discovering, somewhat by accident, that here was a property which would almost certainly make a nice chunk of money and also provide a crutch for him to do interesting things that had very little to do with the actual task of adapting S.E. Hinton's 1967 novel (published when she was just 18!), which came to his attention when a Fresno, CA middle school class voted him the filmmaker they most wanted to see tackle the book that was held in dear esteem by all of them. A fun exercise is to glance over Coppola's filmography to that point, take out all the titles that are spectacularly inappropriate for middle-schoolers, and determine that the class apparently rallied behind Coppola on the strength of his 1968 adaptation of Finian's Rainbow, every kid's favorite musical.

The Outsiders - about which I know nothing at all save that it is the basis for this film, and my apologies to its apparently strong, multi-generational audience of passionate followers for my ignorance - is a pretty basic JD story set in a vaguely defined Oklahoma in a vaguely specified 1960s. It takes place in a small town where teen culture is apparently divided between two gangs: the lower-glass Greasers, and the rich Socs. Our main points of entry in to this world are the two youngest, least-qualified members of the Greasers: 14-year-olds Ponyboy Curtis (C. Thomas Howell) and Johnny Cade (Ralph Macchio). They are chiefly in thrall to Dallas Winston (Matt Dillon), the sort of low-key cad who reads as "charismatic" almost exclusively to younger, impressionable males, but for Ponyboy, at least, the Greasers are a family tradition: among its members are his elder brothers Sodapop (Rob Lowe) and Darrel (Patrick Swayze), who seems to be the oldest and most leaderly of the gang. The boys end up accidentally killing one of the Socs, and go into hiding under the dubious guidance of Dallas; during their exile in the wilds of the Plain states, they manage to heroically and selflessly save some children from a burning church, and return home, to find that heroism hasn't quite wiped the legal slate clean, and also the Socs are plotting a rumble to get back at the Greasers.

Straightforward enough (and about a quarter shorter than the "full" version Coppola presented to Warner Bros., which apparently kept more of the resonance of the book intact - it has since been released to DVD), but there's absolutely no sense at any point that The Outsiders is to any meaningful extent a story of life among the gangs, no matter how much it keeps tapping you on the shoulder to ask, "By the way, did you say something about West Side Story? No, huh? I could have sworn you did. What about Rebel Without a Cause?" It is, instead, an attempt to capture penetrating, iconic imagery of the American West in a way that reflects the particular soulfulness and questioning of these young, tragically dislocated hoodlums. More specifically, it's an overt nod to Gone with the Wind, which is specifically mentioned at multiple points in the dialogue and obviously referenced, especially in the middle of the film, in sequences that crib from that film's famous "silhouettes against an orange-red sky" motif.

It's unapologetic Romanticism, in a film that looks at its teenage characters, with their overheated passions and intense feelings; and then looks at its prospective teenage audience, with its proprietary, emotionally invested ownership of the book; and then decides "well, let's go ahead and be sincere about all this, then". Which is kind of refreshing and bold: a movie about heightened teen melodrama that firmly embraces that melodrama with both arms, trying to find cinematic equivalences to to the heady, potent certitude that this feeling we are feeling is the absolute most important thing ever. The Outsiders is gorgeous, shamelessly so: Coppola and cinematographer Stephen H. Burum invest heavily in draping the perfectly attractive scrublands of Oklahoma, the picture-postcard nostalgic locations, and the slightly-too-clean but soft and peaceable interiors, in dappled lighting and slow movements, and Coppola and editor Anne Goursaud then combine those images in emotionally intuitive rather than narratively driven cuts. Unexpectedly, it turns out to be something like Malick's Badlands for '80s teen audiences (this is, again, most true of the film's middle, which I find to be easily its most compelling sequence: the beginning is over-invested in period signifiers that don't really matter, the end suddenly starts to double down on the plot and climaxes in an impressionistically lovely, but otherwise imprecise gang rumble), right down to the way that the dusky dryness of the setting is both enormously specific in every detail of every building, while also feeling like a dream-soaked Neverland. The textures and sounds of the physical setting are enormously important, that is, while the notion of Oklahoma, 1965, is almost completely besides the point.

Coppola and company do an outstanding job of creating and sustaining a mood through their visuals, and occasional shifts into Expressionism (Ponyboy, recalling his parents' death, has a car apparently drive over his face during a dissolve, with a cut to that car wrecking in a visually and audibly garish shift that's almost funny in its shocking violence), making a film about the idea of being an isolated teenager trying to find love, family, and a place as a series of dense and empty images, with Coppola's father Carmine providing an absolutely terrific score that unsentimentally provides a sense of placelessness, and Howell, excellent in only his second credited film role, seems to absorb all the internal confusion, yearning need, fearful self-doubt, and anger of every movie about juvenile delinquents ever and turn them into an excellent vessel for the film's concepts.

What I'm not as convinced about is that Coppola and company do as good a job, or even a good job, period, at telling the basic story of characters that Hinton set out. In between all the deliberately, self-consciously iconic imagery, the character moments feel a little straightforward and disinvested, and though the film is impressively stocked with young people who would go on to have important and highly visible careers - besides Howell, Dillon, Macchio, Swayze, and Lowe, Diane Lane has a big role, and Tom Cruise and Emilio Estevez both show up - Coppola only really seems to take an interest in Howell, and Macchio and Dillon as the people Howell interacts with the most, leaving the rest of the cast as attractive faces to fill out the frame with business that seems more about creating a sense of movement than doing anything to build character or stress the reality of the world being depicted. And Howell himself is, as I said, more effective at channeling concepts than really clarifying who Ponyboy is: in fact, The Outsiders in this form is largely predicated on Ponyboy not being anyone specific, but being an abstracted concept about "being a lonely teenager". The result is that The Outsiders works entirely as an explication of a mindset rather than as a depiction of individual minds, and while its target audience has, apparently, found this gratifying and legitimising for some 30 years now, the film strikes me as being stubbornly remote, for all its undeniable beauty and talent.

It made its money, anyway: no blockbuster, but enough to ease Coppola back from the nightmare of One from the Heart-induced destitution. It's such a perfect metaphor for '70s cinema transitioning to '80s cinema that I'm almost embarrassed to make it the punchline of a whole review: the artistic madman, tamed and docile, but still making movies he at least can believe in, and all to give the audience exactly what it was asking for and nothing more. It's a lovely film in a lot of ways, for all that it's a little too safe, and it's at any rate a more satisfying example of the artist-as-talented-hack exercise than The Godfather, Part III would prove to be, for starters.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1983

-Moms watching their daughters die of cancer prove shockingly popular in Terms of Endearment

-Tom Cruise in his underwear is popular, but it's not really shocking, in Risky Business

-A Christmas Story is not especially popular at first, but over the years, this will change

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1983

-It's Bond vs. Bond, as the "official" movie Octopussy, starring Roger Moore, outperforms the return of Sean Connery to his most iconic role in Never Say Never Again

-Robert Bresson ends his career with the pseudo-Marxist thriller L'argent

-Bizarre Japanese filmmaker Oshima Nagisa and bizarre British pop star David Bowie collaborate in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence