The 50th Chicago International Film Festival

Winner of the Gold Hugo for Best Film

Screens at CIFF: 10/15 & 10/16

World premiere: 30 August, 2014, Venice International Film Festival

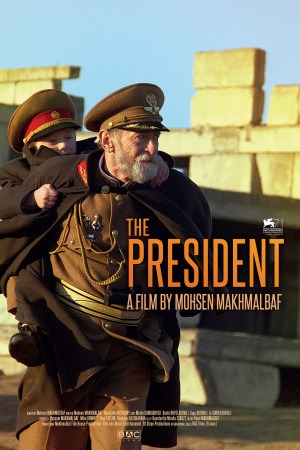

Satire doesn't get much more on-the-nose, snottily sarcastic, or, in fairness, absolutely hilarious as the opening of The President, a most uncharacteristic but hugely welcome surprise from self-exiled Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A narrator waxes rhapsodic about the beauty of the capital city in this nameless (but pretty obviously former Soviet) nation, with special attention paid to the beloved president-for-life, also nameless, whose vision is what caused the city to bathed in attractive modern light. And then we travel up to the presidential palace, where the president himself (Misha Gomiashvili) is sitting with his beloved grandson (Dachi Orvelashvili), indulging the boy's every random question with happy patience, and for a finale, offers to let the boy place a call to have the entire power grid shut down and turned back on over and over again the way that a child of less powerful descent might play with the lights on a Christmas tree. That is: the dictator literally treats the city under his command like a child's toy. No wonder that during one of the dark patches, the city suddenly erupts in revolution.

No, not subtle at all. Funny, though - between Gomiashvili's warm grandpa routine crashing aggressively into the thoughtless brutality of his actions, and the grandson's ridiculously adorable little mini-dictator costume, there's a warped, zingy sense of black comedy here, one that mocks the president with unabashed glee. That's not a tone the film keeps up (it would undoubtedly be too smug and juvenile to bear if that were the case), although it does frequently drift back into angry comedy, ready at any moment to remind us of how ridiculous and awful this character is any time he starts to seem too pathetic.

Which is a real possibility, for The President adopts the shape of a travelogue, in which an old man and his grandson journey through the rural part of their country, learning truths. As the president, deposed in the wake of that revolution (a protracted sequence suggesting that, beyond his customary skill with character and his newfound facility for humor, Makhmalbaf might have a really good action thriller hiding in him, too), wanders through the immense poverty and suffering his policies have caused, he discovers for the first time that actual human beings have been affected by his capricious behavior, and that the love he though all his people had for his regime was actually fear and resentment hiding behind desperately waving his poster around in attempt to avoid becoming the next political prisoner. What this knowledge does not do, as I feared for a while it might, is turn the president soft, like an eastern European Scrooge; it also doesn't quite push him into the territory of Lear wandering the heath in a mad daze, though Lear is undoubtedly in the back of Makhmalbaf and co-writer (and wife) Marziyeh Meshkiny's minds throughout the long middle section of the film, where he prostrates himself more and more, discarding his miltary garb for peasant's clothes and then for a prisoner's cloak.

There is a kind of awareness going on, tempered by humiliation and rage; what is going on, in fact, is that the president is discovering actual humanity for the first time, both in the targets of his dictatorial cruelty and in himself. This couldn't possibly work without such a measured, complicated performance as the one Gomiashvili gives; he reveals weakness and blossoming self-knowledge without requiring that we overlook the fact that the man going through this is a murderer and thug. It's remarkably delicate, how the actor and by extension the film ask us to understand the president without having any notion of our forgiving or liking him.

Essentially the film posits that people are people, even horrible dictators, and as it moves towards its increasingly grim concluding acts, it begins to showcase how tempting the overuse of violent power is to anyone, demonstrating how the revolutionaries are as capable of making life hell for the people of the country as the president himself ever was. It is, at absolutely no credit to its originality, about how power corrupts, a theme of considerable antiquity, though by virtue of always being ignored by everybody, it remains important to keep retelling stories like this. The dictator loves his grandson; he doesn't regard himself as a bad person; he is capable of suffering from cold and hunger and fear. He is a person. The film doesn't spell this out to let him off the hook, but to keep us on our toes, admitting that the potential for evil and violence isn't something that only the monsters are born with.

It's a rich and wonderful character study, light on its feet and sophisticated about re-packaging its insights into how easy it is for humans to go wrong, hard and savage in depicting what that wrongness looks like. Whether considering the effects of the president's own depravities, or of the new depravities being visited upon the world by his enemies, the film confronts everything with a steady, unblinking eye; when recognising that the revolutionaries or the president are people, it reverses into beautiful poetry, most satisfyingly in a lengthy circular tracking shot that reduces the president and his most miserable victims to the status of humans all needing more connection to the rest of humanity. It is a film fascinated by people, much too fascinated to hate even the worst of them; it's that, not the satire nor the violence nor the sometimes clumsy use of the child as an purified innocent, that makes this a captivating piece of storytelling and intimate work of cinema.

Screens at CIFF: 10/15 & 10/16

World premiere: 30 August, 2014, Venice International Film Festival

Satire doesn't get much more on-the-nose, snottily sarcastic, or, in fairness, absolutely hilarious as the opening of The President, a most uncharacteristic but hugely welcome surprise from self-exiled Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A narrator waxes rhapsodic about the beauty of the capital city in this nameless (but pretty obviously former Soviet) nation, with special attention paid to the beloved president-for-life, also nameless, whose vision is what caused the city to bathed in attractive modern light. And then we travel up to the presidential palace, where the president himself (Misha Gomiashvili) is sitting with his beloved grandson (Dachi Orvelashvili), indulging the boy's every random question with happy patience, and for a finale, offers to let the boy place a call to have the entire power grid shut down and turned back on over and over again the way that a child of less powerful descent might play with the lights on a Christmas tree. That is: the dictator literally treats the city under his command like a child's toy. No wonder that during one of the dark patches, the city suddenly erupts in revolution.

No, not subtle at all. Funny, though - between Gomiashvili's warm grandpa routine crashing aggressively into the thoughtless brutality of his actions, and the grandson's ridiculously adorable little mini-dictator costume, there's a warped, zingy sense of black comedy here, one that mocks the president with unabashed glee. That's not a tone the film keeps up (it would undoubtedly be too smug and juvenile to bear if that were the case), although it does frequently drift back into angry comedy, ready at any moment to remind us of how ridiculous and awful this character is any time he starts to seem too pathetic.

Which is a real possibility, for The President adopts the shape of a travelogue, in which an old man and his grandson journey through the rural part of their country, learning truths. As the president, deposed in the wake of that revolution (a protracted sequence suggesting that, beyond his customary skill with character and his newfound facility for humor, Makhmalbaf might have a really good action thriller hiding in him, too), wanders through the immense poverty and suffering his policies have caused, he discovers for the first time that actual human beings have been affected by his capricious behavior, and that the love he though all his people had for his regime was actually fear and resentment hiding behind desperately waving his poster around in attempt to avoid becoming the next political prisoner. What this knowledge does not do, as I feared for a while it might, is turn the president soft, like an eastern European Scrooge; it also doesn't quite push him into the territory of Lear wandering the heath in a mad daze, though Lear is undoubtedly in the back of Makhmalbaf and co-writer (and wife) Marziyeh Meshkiny's minds throughout the long middle section of the film, where he prostrates himself more and more, discarding his miltary garb for peasant's clothes and then for a prisoner's cloak.

There is a kind of awareness going on, tempered by humiliation and rage; what is going on, in fact, is that the president is discovering actual humanity for the first time, both in the targets of his dictatorial cruelty and in himself. This couldn't possibly work without such a measured, complicated performance as the one Gomiashvili gives; he reveals weakness and blossoming self-knowledge without requiring that we overlook the fact that the man going through this is a murderer and thug. It's remarkably delicate, how the actor and by extension the film ask us to understand the president without having any notion of our forgiving or liking him.

Essentially the film posits that people are people, even horrible dictators, and as it moves towards its increasingly grim concluding acts, it begins to showcase how tempting the overuse of violent power is to anyone, demonstrating how the revolutionaries are as capable of making life hell for the people of the country as the president himself ever was. It is, at absolutely no credit to its originality, about how power corrupts, a theme of considerable antiquity, though by virtue of always being ignored by everybody, it remains important to keep retelling stories like this. The dictator loves his grandson; he doesn't regard himself as a bad person; he is capable of suffering from cold and hunger and fear. He is a person. The film doesn't spell this out to let him off the hook, but to keep us on our toes, admitting that the potential for evil and violence isn't something that only the monsters are born with.

It's a rich and wonderful character study, light on its feet and sophisticated about re-packaging its insights into how easy it is for humans to go wrong, hard and savage in depicting what that wrongness looks like. Whether considering the effects of the president's own depravities, or of the new depravities being visited upon the world by his enemies, the film confronts everything with a steady, unblinking eye; when recognising that the revolutionaries or the president are people, it reverses into beautiful poetry, most satisfyingly in a lengthy circular tracking shot that reduces the president and his most miserable victims to the status of humans all needing more connection to the rest of humanity. It is a film fascinated by people, much too fascinated to hate even the worst of them; it's that, not the satire nor the violence nor the sometimes clumsy use of the child as an purified innocent, that makes this a captivating piece of storytelling and intimate work of cinema.

Categories: ciff, eastern european cinema, political movies, satire, travelogues