Coming to get you

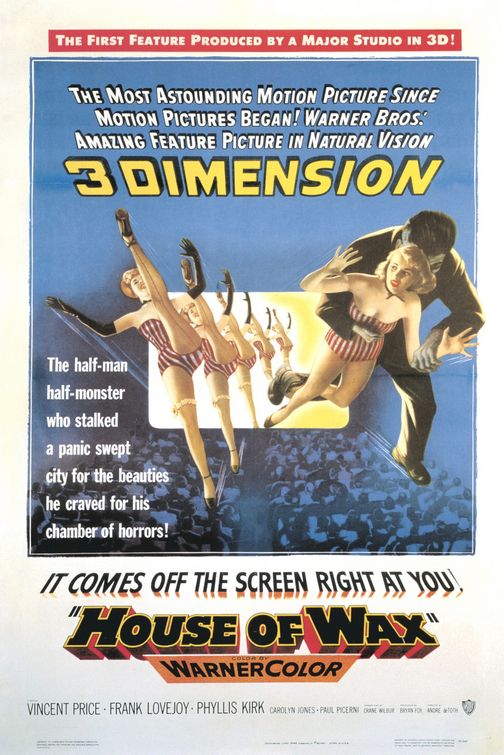

History remembers 1953's House of Wax as the first big studio film shot in 3-D during that gimmick's earliest incarnation. History remembers this so well, in fact, that history tends to overlook that House of Wax has perhaps even more significant a claim to fame: it was more or less the movie that first linked Vincent Price to the horror genre. I can't make that claim entirely divorced of hedging: it would be another half-decade until he appeared in The Fly, the first film in the almost uninterrupted run of horror movies he'd appear in throughout the second half of his career (we could maybe stretch a point and call the starting point of this run his 1957 appearance as a non-threatening Satan in the horror-free The Story of Mankind), and he'd already appeared in three horror-ish films in 1939 and '40, Tower of London, The Invisible Man Returns, and The House of the Seven Gables. But there were a lot of years and movie separating those films from House of Wax, and even if it took a while for him to stumble into a follow up, it was this film that created, perfectly formed in its first appearance, the archetypal Vincent Price Bad Guy. To wit, an erudite, well-educated genius who is turned by tragedy into a crazed madman willing to commit any number of murders to satiate his muse. And he's disfigured, to boot, an unnecessary but helpful addition to the form.

The film itself was a fairly loose remake of 1933's Mystery of the Wax Museum (which is, ironically, most significant for being a last: it was the final major studio feature shot in 2-color Technicolor), which means basically that the opening sequence, climax, and narrative hook are all the same, but the mix of characters is completely different. Mostly because Mystery of the Wax Museum was every inch an early-'30s movie, and things like fast-talking girl reporters and Depression hucksters weren't part of the cinematic landscape anymore in 1953. It's the same basic nugget, though: Henry Jarrod (Price) is the genius creator of the finest wax museum in New York around the turn of the century, but he lacks the mercenary edge to exploit his talents for profit. This aggravates his business partner Matthew Burke (Roy Roberts), who elects to set the museum on fire to collect the insurance money. Jarrod will have none of this, and tries to fight Burke, but he's overpowered and left for dead as the fires rage.

Some years later, Burke is enjoying the fruits of his arson, swanning around New York with his flighty girlfriend Cathy Gray (Carolyn Jones), but this all comes to a crashing halt one night when he's attacked in his apartment by a man all in black, of whose features we can see only that they appear to be grotesquely scarred. This killer stages Burke's death to look like a suicide by hanging, and in hardly any time, he chases after Cathy, as well; but just as he's strangled the life out of her, he's interrupted by her roommate Sue Allen (Phyllis Kirk), who flees in terror and finds refuge in the home of her mother's friend, Mrs. Andrews (Angela Clarke), and more to the point, her friend's hunky son Scott (Paul Picerni). Scott is a sculptor, terribly excited to study at the new wax museum that's about to open, and guess who's running it: the not-so-burned-to-death Henry Jarrod, whose hands have been uselessly crippled and who uses a wheelchair to get around, but is otherwise in fine shape after his ordeal, and anxious to finish rebuilding his great collection with the help of two shifty assistants, Leon (Nedrick Young) and the burly, mute Igor (Charles Bronson back in the wee early days of his career, still using his birth name of Charles Buchinsky).

Scott is amazed by the detail and lifelike quality of Jarrod's work, but not half as amazed as Sue, who finds in the sculptor's new Joan of Arc statue the very spitting image of the dead Cathy, whose body was stolen from the morgue. At this point, even the most naïve of 1950s audiences is pretty much up to speed with the movie, which acts like it's a mystery, though the only thing that's even slightly questionable by the time the film hits the intermission at its halfway point (the technological limitations of early 3-D meant that only around 45 minutes could be played straight through) is whether the hideous facial scars are Jarrod's disguise, or if his apparently hale and hearty face is the mask covering his wounds. And even this isn't much of a surprise, though even the film seems guiltily aware that, in fact, a wax mask would be brittle and unyielding and not really likely to convince anybody that it's a real face.

At the basic level of communicating its story, House of Wax really isn't as strong as Mystery of the Wax Museum, simply because it's so astonishingly predictable, and with the benefit of hindsight pertaining to Price's career, it's easy to get out in front of it almost from before it even starts. In every other way, though, I far prefer the remake, which is one of the most absolutely fun of all horror studio pictures in the 1950s. It would be frivolous to avoid admitting right off that a big part of this is that same 3-D gimmick: despite being infamously directed by one-eyed André De Toth, who thus had no idea what the hell he was doing or what it looked like in the end, House of Wax has some of the most engaging dimensional effects ever, both in terms of creating a deeper, richer world, and in terms of sheer idiot spectacle. The second half is introduced with a lengthy sequence in which a barker (Reggie Rymal) entices people to come to the House of Wax by showing off all kinds of tricks with a paddle ball on the longest elastic string you could imagine - absolute gaudy bullshit that makes no sense whatsoever on a story level, and even the other characters know it. It might well be the most overt "you're watching a 3-D movie, so let's throw shit in your face" scene I have ever seen outside of a theme park attraction. And I am not ashamed to confess that I love it.

But in other places, the 3-D adds wonderfully to the inherently spooky atmosphere of the wax museum: it's slightly exaggerated, stretched for effect, and it place the wax statues in a position where they feel hyper-present, in way, all their limbs and poses distended in an aggressive way. And when that fire starts! It's one of the absolute best moments of 3-D as immersion into a dramatic, distressing situation ever filmed. Now, that leaves us with a good 65 minutes out of 88 where the 3-D pretty much just sits there doing nothing at all: no Pina is this, where every frame is aware of the depth and shape it offers. It's not even Creature from the Black Lagoon. Beyond question, though, the film gains a lot of impact and effect from its use of the technology: I have seen and enjoyed in 2-D in the past, but it absolutely belongs on the list of films that are just plain better when they have that added dimension.

On the other hand, ol' Flat Vision De Toth, as I doubt very much that he was called at the time, turned out to be great for the film in one respect: because he wasn't thinking of it in terms of dimensional gags, he was driven to make it work on its own terms as a piece of visual storytelling, and while being in full color means that House of Wax isn't nearly the moodiest or most vividly atmospheric of '50s horror pictures, it's pretty damn impressive just how much mood it gets, whether from the creepy artifice of the wax museum itself, or from Jarrod's torture chamber-esque molding room in the basement. It's not only because of its star that the film looks forward to the Roger Corman cycle of Edgar Allan Poe movies from dawn of the '60s: there's a similar use of great sets lit with a certain mustiness and gloom to create a hugely persuasive world for the gaudy, silly action to take place.

And about that star: we can talk about 3-D or sets or even the rest of the solid cast (Carolyn Jones rises to pretty fantastic in her twittery, weird performance, the rest stay stalled at "good enough to get the job done), but the reason House of Wax works is Vincent Price. It really is that simple. That man had screen presence like nobody's business, and a flawless, unmatched ability to play melodrama in a relaxed, naturalistic way. As good as that was in his early roles as a shady lover or criminal, and as enjoyably as he undoubtedly is when he's playing the hero of his horror movies, he was always at his very best playing theatrically expansive villains, and with Jarrod, we even get to see how that robust hamminess evolves out of the tamped-down enthusiasm he shows in the earliest scenes, when he's merely an eccentric artist. The transformation from that to the declamatory monster of the final scenes is as evocative as anything in the script at dramatising Jarrod's descent into madness, and the way that Price plays through his thick make-up rather than using it as a cheat (a trick he'd refine into mastery by the time of The Abominable Dr. Phibes, where he'd give a rich, elaborate performance despite being unable to move his face at all) gives a fullness and even pathetic scope to Jarrod's monstrosity that makes him one of the most engaging of all '50s horror madmen.

The scenario is clunky enough, and there are just enough flat-out dumb moments - the film's very final beat, a lame 3-D gag, is among the worst - that I can't in good faith call this one of the decade's standout horror pictures, but it's awfully damn entertaining, and it's essential viewing for Price alone. A horror film about the high cost of giving into mindless spectacle, it's awfully satisfying mindless spectacle itself, and in any number of dimensions, it's a delightfully garish exercise in low-grade creeps.

The film itself was a fairly loose remake of 1933's Mystery of the Wax Museum (which is, ironically, most significant for being a last: it was the final major studio feature shot in 2-color Technicolor), which means basically that the opening sequence, climax, and narrative hook are all the same, but the mix of characters is completely different. Mostly because Mystery of the Wax Museum was every inch an early-'30s movie, and things like fast-talking girl reporters and Depression hucksters weren't part of the cinematic landscape anymore in 1953. It's the same basic nugget, though: Henry Jarrod (Price) is the genius creator of the finest wax museum in New York around the turn of the century, but he lacks the mercenary edge to exploit his talents for profit. This aggravates his business partner Matthew Burke (Roy Roberts), who elects to set the museum on fire to collect the insurance money. Jarrod will have none of this, and tries to fight Burke, but he's overpowered and left for dead as the fires rage.

Some years later, Burke is enjoying the fruits of his arson, swanning around New York with his flighty girlfriend Cathy Gray (Carolyn Jones), but this all comes to a crashing halt one night when he's attacked in his apartment by a man all in black, of whose features we can see only that they appear to be grotesquely scarred. This killer stages Burke's death to look like a suicide by hanging, and in hardly any time, he chases after Cathy, as well; but just as he's strangled the life out of her, he's interrupted by her roommate Sue Allen (Phyllis Kirk), who flees in terror and finds refuge in the home of her mother's friend, Mrs. Andrews (Angela Clarke), and more to the point, her friend's hunky son Scott (Paul Picerni). Scott is a sculptor, terribly excited to study at the new wax museum that's about to open, and guess who's running it: the not-so-burned-to-death Henry Jarrod, whose hands have been uselessly crippled and who uses a wheelchair to get around, but is otherwise in fine shape after his ordeal, and anxious to finish rebuilding his great collection with the help of two shifty assistants, Leon (Nedrick Young) and the burly, mute Igor (Charles Bronson back in the wee early days of his career, still using his birth name of Charles Buchinsky).

Scott is amazed by the detail and lifelike quality of Jarrod's work, but not half as amazed as Sue, who finds in the sculptor's new Joan of Arc statue the very spitting image of the dead Cathy, whose body was stolen from the morgue. At this point, even the most naïve of 1950s audiences is pretty much up to speed with the movie, which acts like it's a mystery, though the only thing that's even slightly questionable by the time the film hits the intermission at its halfway point (the technological limitations of early 3-D meant that only around 45 minutes could be played straight through) is whether the hideous facial scars are Jarrod's disguise, or if his apparently hale and hearty face is the mask covering his wounds. And even this isn't much of a surprise, though even the film seems guiltily aware that, in fact, a wax mask would be brittle and unyielding and not really likely to convince anybody that it's a real face.

At the basic level of communicating its story, House of Wax really isn't as strong as Mystery of the Wax Museum, simply because it's so astonishingly predictable, and with the benefit of hindsight pertaining to Price's career, it's easy to get out in front of it almost from before it even starts. In every other way, though, I far prefer the remake, which is one of the most absolutely fun of all horror studio pictures in the 1950s. It would be frivolous to avoid admitting right off that a big part of this is that same 3-D gimmick: despite being infamously directed by one-eyed André De Toth, who thus had no idea what the hell he was doing or what it looked like in the end, House of Wax has some of the most engaging dimensional effects ever, both in terms of creating a deeper, richer world, and in terms of sheer idiot spectacle. The second half is introduced with a lengthy sequence in which a barker (Reggie Rymal) entices people to come to the House of Wax by showing off all kinds of tricks with a paddle ball on the longest elastic string you could imagine - absolute gaudy bullshit that makes no sense whatsoever on a story level, and even the other characters know it. It might well be the most overt "you're watching a 3-D movie, so let's throw shit in your face" scene I have ever seen outside of a theme park attraction. And I am not ashamed to confess that I love it.

But in other places, the 3-D adds wonderfully to the inherently spooky atmosphere of the wax museum: it's slightly exaggerated, stretched for effect, and it place the wax statues in a position where they feel hyper-present, in way, all their limbs and poses distended in an aggressive way. And when that fire starts! It's one of the absolute best moments of 3-D as immersion into a dramatic, distressing situation ever filmed. Now, that leaves us with a good 65 minutes out of 88 where the 3-D pretty much just sits there doing nothing at all: no Pina is this, where every frame is aware of the depth and shape it offers. It's not even Creature from the Black Lagoon. Beyond question, though, the film gains a lot of impact and effect from its use of the technology: I have seen and enjoyed in 2-D in the past, but it absolutely belongs on the list of films that are just plain better when they have that added dimension.

On the other hand, ol' Flat Vision De Toth, as I doubt very much that he was called at the time, turned out to be great for the film in one respect: because he wasn't thinking of it in terms of dimensional gags, he was driven to make it work on its own terms as a piece of visual storytelling, and while being in full color means that House of Wax isn't nearly the moodiest or most vividly atmospheric of '50s horror pictures, it's pretty damn impressive just how much mood it gets, whether from the creepy artifice of the wax museum itself, or from Jarrod's torture chamber-esque molding room in the basement. It's not only because of its star that the film looks forward to the Roger Corman cycle of Edgar Allan Poe movies from dawn of the '60s: there's a similar use of great sets lit with a certain mustiness and gloom to create a hugely persuasive world for the gaudy, silly action to take place.

And about that star: we can talk about 3-D or sets or even the rest of the solid cast (Carolyn Jones rises to pretty fantastic in her twittery, weird performance, the rest stay stalled at "good enough to get the job done), but the reason House of Wax works is Vincent Price. It really is that simple. That man had screen presence like nobody's business, and a flawless, unmatched ability to play melodrama in a relaxed, naturalistic way. As good as that was in his early roles as a shady lover or criminal, and as enjoyably as he undoubtedly is when he's playing the hero of his horror movies, he was always at his very best playing theatrically expansive villains, and with Jarrod, we even get to see how that robust hamminess evolves out of the tamped-down enthusiasm he shows in the earliest scenes, when he's merely an eccentric artist. The transformation from that to the declamatory monster of the final scenes is as evocative as anything in the script at dramatising Jarrod's descent into madness, and the way that Price plays through his thick make-up rather than using it as a cheat (a trick he'd refine into mastery by the time of The Abominable Dr. Phibes, where he'd give a rich, elaborate performance despite being unable to move his face at all) gives a fullness and even pathetic scope to Jarrod's monstrosity that makes him one of the most engaging of all '50s horror madmen.

The scenario is clunky enough, and there are just enough flat-out dumb moments - the film's very final beat, a lame 3-D gag, is among the worst - that I can't in good faith call this one of the decade's standout horror pictures, but it's awfully damn entertaining, and it's essential viewing for Price alone. A horror film about the high cost of giving into mindless spectacle, it's awfully satisfying mindless spectacle itself, and in any number of dimensions, it's a delightfully garish exercise in low-grade creeps.

Categories: horror, mysteries, the third dimension, vincent price, worthy remakes