Now museum, now you don't

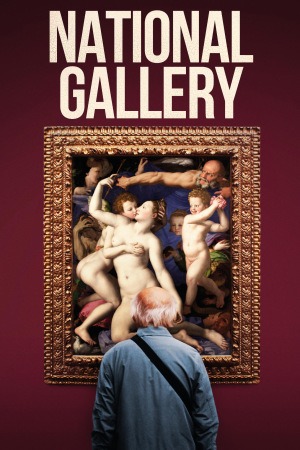

Last year's superlative At Berkeley dropped me squarely into the "Frederick Wiseman, where have you been all my life?" phase of my cinephilia, and now National Gallery confirms it: this man's documentaries are magnificent, essential, pure cinema. You can draw a line straight back from National Gallery's patient and inflectionless shots of people standing in the rooms of the titular museum all the way back to Auguste and Louis Lumière's objective viewpoint of Parisian crowds, and yet National Gallery feels profoundly modern in every way. It has as much to say about life and culture in the 2010s as any other movie I've seen all year, while being just a hell of a lot of fun to watch for its deep access to the inner workings of a living institution that most of us won't have had a chance to see. At Berkeley is probably "better" with its epic scale and monumental nature, but National Gallery, with far more editing that has shaped it to offer more of a clear progression of arguments, is rather more enjoyable, if I say so myself.

The subject, of course, is London's National Gallery, which Wiseman (doubling down as sound recordist, on top of directing and editing) visited in 2011 and 2012, during its exhibition of the works of Leonardo Da Vinci (this means, please note, that Wiseman was cutting At Berkeley and National Gallery more or less in tandem, which makes the fact that they're both amazing even more dumbfounding). But it is not a documentary about Leonardo's work. Nor, really, about any of the important works in the National Gallery collection, though many pieces are thoroughly discussed and analysed by onscreen experts over the course of the film's three hours.

What it is about, instead, is how art is curated and sold to people in the buzzy world of the 2010s. There's only a small amount of screentime devoted to the Gallery's bureaucracy, but the longest such scene comes very near the beginning, with a meeting of administrators discussing with polite British acrimony whether it makes sense for the Gallery to associate itself with a charity event, thereby setting A Precedent (which, even the most pro-charity people agree, is a thing that must absolutely not be set). The argument for it is that in a world with an ever-increasing number of diversions, people need a reason to care about the United Kingdom's publicly-owned collection of some of the most important European paintings gathered under one roof, with its attendant veneer of boring conservative respectability.

That's a conversation that never stops echoing throughout the remainder of the film, which becomes, in great part, a study of the way that art experts try to package and explain art. We see lecturers explaining to crowds of tourists how to view art through a modern lens and through a suitably contextualised historical one. We see the fussy, protracted work of tweaking lights to show off the right aspects of a painting. We see the scientific process of restoring damaged paintings and hear an extensive artistic description of what aesthetic philosophy the scientist needs to adopt in order to attempt that restoration. In a cheeky moment that reveals Wiseman has quite the dry sense of humor, we see another documentary team filming the same collection, though with an authoritative narrator who insists on interpretations, as opposed to Wiseman's ultra-detached willingness to stand back and let whoever happens to be in front of the camera do their thing.

Even that's the shallow end of the rabbit hole. For the longer we spend with the historians, lecturers, and administrators explaining within themselves and to outsiders how best to curate collections and then explain to an audience what the importance of all this art is, the more it becomes apparent that Wiseman has basically done the same thing. Taking a pile of God knows how much footage, deciding what story to tell with it, and then cutting it down to a streamlined three hours (which, by virtue of the variety and brevity of scenes, is absolutely never boring), in which we see plenty of explanations to an audience on both sides of the screen of why this art is important. The construction of Wiseman's National Gallery is very much like the construction of the actual edifice which shares its name, a link that the movie fully embraces, insomuch as the hands-off technique that defines the film "embraces" much of anything.

The film ends up being less an argument that classical art does or should still speak to us plugged-in moderns, and more an examination of the multifaceted ways in which it can engage everyone from children to students to art world professionals, and even a group of blind people, in one startling and beautiful scene showcasing just how flexible we can be in our approach to teaching and enjoying art. It's never didactic or politicised, and let's be thankful for that: instead, it simply leads by example, making every new topic it turns its camera to seem fascinating and complex and tremendously exciting, whether it's as revelatory as watching a restorer strip away a thick veneer of aged varnish right before our eyes, or as minute as watching a discussion of where to put the ropes in an exhibition space to correctly guide the viewer's eye and feet. Along the way, a host of interpretive models are forwarded, from the arch-democracy of "I think this one looks like she's texting!" of a centuries-old painting, to the heavily proscribed philosophy that we can only really judge a painting if we see it in the exact room that it was designed for.

It's all the more fascinating because Wiseman simply presents it to us as a flow of ideas and moments and images that present fine art as both timeless and very current, abstractions of light, shape, and mood that are also physical objects which react to the ravages of time and the specifics of their environment in any number of ways. National Gallery finds angles to view these paintings and their presentation as a ongoing process, a job, and an end result, and in all these modes argues silently but persuasively that paying any kind of attention to our combined cultural legacy is the most important thing, not getting it "right" or being sufficiently respectful and stuffy about it. It is, simply, a great film about what art is, with the justified pride to include itself under that umbrella. As it should, for this is easily one of the best films of 2014.

The subject, of course, is London's National Gallery, which Wiseman (doubling down as sound recordist, on top of directing and editing) visited in 2011 and 2012, during its exhibition of the works of Leonardo Da Vinci (this means, please note, that Wiseman was cutting At Berkeley and National Gallery more or less in tandem, which makes the fact that they're both amazing even more dumbfounding). But it is not a documentary about Leonardo's work. Nor, really, about any of the important works in the National Gallery collection, though many pieces are thoroughly discussed and analysed by onscreen experts over the course of the film's three hours.

What it is about, instead, is how art is curated and sold to people in the buzzy world of the 2010s. There's only a small amount of screentime devoted to the Gallery's bureaucracy, but the longest such scene comes very near the beginning, with a meeting of administrators discussing with polite British acrimony whether it makes sense for the Gallery to associate itself with a charity event, thereby setting A Precedent (which, even the most pro-charity people agree, is a thing that must absolutely not be set). The argument for it is that in a world with an ever-increasing number of diversions, people need a reason to care about the United Kingdom's publicly-owned collection of some of the most important European paintings gathered under one roof, with its attendant veneer of boring conservative respectability.

That's a conversation that never stops echoing throughout the remainder of the film, which becomes, in great part, a study of the way that art experts try to package and explain art. We see lecturers explaining to crowds of tourists how to view art through a modern lens and through a suitably contextualised historical one. We see the fussy, protracted work of tweaking lights to show off the right aspects of a painting. We see the scientific process of restoring damaged paintings and hear an extensive artistic description of what aesthetic philosophy the scientist needs to adopt in order to attempt that restoration. In a cheeky moment that reveals Wiseman has quite the dry sense of humor, we see another documentary team filming the same collection, though with an authoritative narrator who insists on interpretations, as opposed to Wiseman's ultra-detached willingness to stand back and let whoever happens to be in front of the camera do their thing.

Even that's the shallow end of the rabbit hole. For the longer we spend with the historians, lecturers, and administrators explaining within themselves and to outsiders how best to curate collections and then explain to an audience what the importance of all this art is, the more it becomes apparent that Wiseman has basically done the same thing. Taking a pile of God knows how much footage, deciding what story to tell with it, and then cutting it down to a streamlined three hours (which, by virtue of the variety and brevity of scenes, is absolutely never boring), in which we see plenty of explanations to an audience on both sides of the screen of why this art is important. The construction of Wiseman's National Gallery is very much like the construction of the actual edifice which shares its name, a link that the movie fully embraces, insomuch as the hands-off technique that defines the film "embraces" much of anything.

The film ends up being less an argument that classical art does or should still speak to us plugged-in moderns, and more an examination of the multifaceted ways in which it can engage everyone from children to students to art world professionals, and even a group of blind people, in one startling and beautiful scene showcasing just how flexible we can be in our approach to teaching and enjoying art. It's never didactic or politicised, and let's be thankful for that: instead, it simply leads by example, making every new topic it turns its camera to seem fascinating and complex and tremendously exciting, whether it's as revelatory as watching a restorer strip away a thick veneer of aged varnish right before our eyes, or as minute as watching a discussion of where to put the ropes in an exhibition space to correctly guide the viewer's eye and feet. Along the way, a host of interpretive models are forwarded, from the arch-democracy of "I think this one looks like she's texting!" of a centuries-old painting, to the heavily proscribed philosophy that we can only really judge a painting if we see it in the exact room that it was designed for.

It's all the more fascinating because Wiseman simply presents it to us as a flow of ideas and moments and images that present fine art as both timeless and very current, abstractions of light, shape, and mood that are also physical objects which react to the ravages of time and the specifics of their environment in any number of ways. National Gallery finds angles to view these paintings and their presentation as a ongoing process, a job, and an end result, and in all these modes argues silently but persuasively that paying any kind of attention to our combined cultural legacy is the most important thing, not getting it "right" or being sufficiently respectful and stuffy about it. It is, simply, a great film about what art is, with the justified pride to include itself under that umbrella. As it should, for this is easily one of the best films of 2014.