This turbulent priest

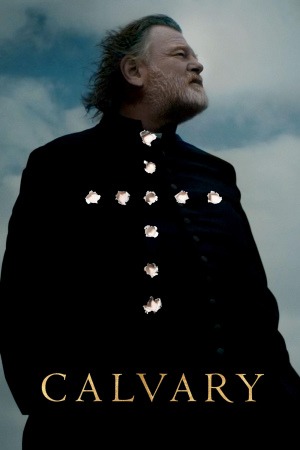

Titling one's movie Calvary, as writer-director John Michael McDonagh has done in his second feature (and also the second entry in his project to give amazing lead roles to Brendan Gleeson), boxes things in pretty well. It has to be a film with a walking, talking Christ surrogate, pretty much, and Calvary's is a doozy: Father James (Gleeson), one of two priests in a rural Irish parish, who spends the film's opening scene taking confession from one of his flock who bluntly announces an intention to kill the priest the following Sunday. And this is specifically because Father James is so totally, undeniably innocent of any wrongdoing of any kind, that the killer has chosen him to be the pure sacrificial lamb to atone for the sins of a Church that hasn't sufficiently acknowledged its sin of allowing pedophiles the protection of the cloth.

In another universe, this could serve as the opening to a crackling thriller about a targeted innocent hunting down his unknown assailant, a kind of religious-themed D.O.A.; but my oh my, that's not even slightly the film McDonagh had in mind to make. Fairly early on, Father James speaks to his bishop (David McSavage), and acknowledges that he recognised the man's voice in the confessional; so much for being a mystery. And despite having this knowledge, and being informed by the bishop that this situation doesn't fall under the sanctity protecting those in the confessional (the would-be killer not showing any desire to atone), Father James shows no interest in stopping his assailant. Instead, he spends what may very well be the last week of his life trying to do the best he can to better the lives of those in his small community, and to feel his way around the broken relationship between himself and his daughter Fiona (Kelly Reilly), born prior to his entry into the priesthood upon the occasion of his wife's death.

Calvary is, if this doesn't seem like an artificial construction, an extremely lapsed-Catholic movie. It could only possibly have been made in a country dominated by Catholicism and by a native of that country; as much as it is concerned with any other topic under the sun, the film is obsessively interested in the waning authority of the Church in a place where it once was simply assumed to be the primary force guiding the lives of everyone living there. It's a film whose characters and story are so nakedly symbolic that it doesn't care even a little bit if that symbolism gets overbearing or trumps the realistic logic of the scenario, which I will confess to finding immensely rewarding. Grappling with national religious identity in the form of a character study is not a task for the squeamish or the subtle, and for all its political cartoon filing of characters into types like The Atheist, Dr. Frank Harte (Aiden Gillen), The Rich Man, Michael Fitzgerald (Dylan Moran), The Foreigner, Simon (Isaach De Bankolé), and so on, there's an organic texture to the way that Calvary assembles and cycles through its characters that keeps it from feeling forced or overly messagey.

As the center of this swirl of metaphorical approaches to the Church's role in modern times, Gleeson has to play three layers all at once, two of them wholly symbolic, and still make Father James feel like an actual, plausible human being. The film cheats its way into it: McDonagh's script unabashedly conforms itself to the actor and makes use of all his best skills, without having to necessarily tax Gleeson to do much more than stand with his mournful beardy expression in some of the quieter moments. Then again, McDonagh and Gleeson developed the character and the script together, so the work of creating a character goes deeper than just standing in front of a camera and reciting lines, in this case. However it came to be, Gleeson is absolutely devastating in the role, one of the great triumphs of commanding screen presence of the year. Evoking Father James's inner fear and resignation and willingness to assume guilt through long wordless stretches and the heavy way he carries his body, Gleeson provides the movie with all the shape and focus it needs to carry off its broad ambitions.

Not that he's the whole movie, or anything; frequently, he's put in an entirely reactive role to the splashy characters surrounding him. The film loves its supporting characters: it gives all of them big showcase moments and all the best lines of tart dialogue, adding a pitch-black hilarity that keeps the film from feeling too damn serious too often. A film about religion, religious institutions, and pessimistic faith though it is, Calvary is grounded in the messy stuff of day-to-day humanity, and its stately movement from one character to the next as each scene glides by gives all of its humans a chance to shine.

Larry Smith's grey-washed cinematography lends a sense of terrible Romantic grandeur to the Irish landscapes (an easy thing to do, in fairness) and aging interiors alike reinforcing and deepening the shifting emotions of the story, while Chris Gill's editing provides a crisp momentum that draws us unto scenes, and carefully shapes our relationship to James. So for for all that it's driven by ideas and screenwriterly conceits, it doesn't drop the ball on being a well-built piece of cinema. The ideas are what count most, though: they're a bit bleak at times and willing to let theme triumph over characters every so often (including, probably, the ending shots), but presented with impressive thoughtfulness and intellectual grounding, and just enough humor that it doesn't burn on the way down. It is, in more than a few ways, an Irish Catholic variant on the scorched-earth Swedish Lutheranism of Ingmar Bergman's Winter Light; not a recipe for a breezy fun time at the movies, but when you're in the mood to really grapple, I mean, just grapple with religion and sociology and dense character acting, you could hardly find anything better in the contemporary cinema landscape.

In another universe, this could serve as the opening to a crackling thriller about a targeted innocent hunting down his unknown assailant, a kind of religious-themed D.O.A.; but my oh my, that's not even slightly the film McDonagh had in mind to make. Fairly early on, Father James speaks to his bishop (David McSavage), and acknowledges that he recognised the man's voice in the confessional; so much for being a mystery. And despite having this knowledge, and being informed by the bishop that this situation doesn't fall under the sanctity protecting those in the confessional (the would-be killer not showing any desire to atone), Father James shows no interest in stopping his assailant. Instead, he spends what may very well be the last week of his life trying to do the best he can to better the lives of those in his small community, and to feel his way around the broken relationship between himself and his daughter Fiona (Kelly Reilly), born prior to his entry into the priesthood upon the occasion of his wife's death.

Calvary is, if this doesn't seem like an artificial construction, an extremely lapsed-Catholic movie. It could only possibly have been made in a country dominated by Catholicism and by a native of that country; as much as it is concerned with any other topic under the sun, the film is obsessively interested in the waning authority of the Church in a place where it once was simply assumed to be the primary force guiding the lives of everyone living there. It's a film whose characters and story are so nakedly symbolic that it doesn't care even a little bit if that symbolism gets overbearing or trumps the realistic logic of the scenario, which I will confess to finding immensely rewarding. Grappling with national religious identity in the form of a character study is not a task for the squeamish or the subtle, and for all its political cartoon filing of characters into types like The Atheist, Dr. Frank Harte (Aiden Gillen), The Rich Man, Michael Fitzgerald (Dylan Moran), The Foreigner, Simon (Isaach De Bankolé), and so on, there's an organic texture to the way that Calvary assembles and cycles through its characters that keeps it from feeling forced or overly messagey.

As the center of this swirl of metaphorical approaches to the Church's role in modern times, Gleeson has to play three layers all at once, two of them wholly symbolic, and still make Father James feel like an actual, plausible human being. The film cheats its way into it: McDonagh's script unabashedly conforms itself to the actor and makes use of all his best skills, without having to necessarily tax Gleeson to do much more than stand with his mournful beardy expression in some of the quieter moments. Then again, McDonagh and Gleeson developed the character and the script together, so the work of creating a character goes deeper than just standing in front of a camera and reciting lines, in this case. However it came to be, Gleeson is absolutely devastating in the role, one of the great triumphs of commanding screen presence of the year. Evoking Father James's inner fear and resignation and willingness to assume guilt through long wordless stretches and the heavy way he carries his body, Gleeson provides the movie with all the shape and focus it needs to carry off its broad ambitions.

Not that he's the whole movie, or anything; frequently, he's put in an entirely reactive role to the splashy characters surrounding him. The film loves its supporting characters: it gives all of them big showcase moments and all the best lines of tart dialogue, adding a pitch-black hilarity that keeps the film from feeling too damn serious too often. A film about religion, religious institutions, and pessimistic faith though it is, Calvary is grounded in the messy stuff of day-to-day humanity, and its stately movement from one character to the next as each scene glides by gives all of its humans a chance to shine.

Larry Smith's grey-washed cinematography lends a sense of terrible Romantic grandeur to the Irish landscapes (an easy thing to do, in fairness) and aging interiors alike reinforcing and deepening the shifting emotions of the story, while Chris Gill's editing provides a crisp momentum that draws us unto scenes, and carefully shapes our relationship to James. So for for all that it's driven by ideas and screenwriterly conceits, it doesn't drop the ball on being a well-built piece of cinema. The ideas are what count most, though: they're a bit bleak at times and willing to let theme triumph over characters every so often (including, probably, the ending shots), but presented with impressive thoughtfulness and intellectual grounding, and just enough humor that it doesn't burn on the way down. It is, in more than a few ways, an Irish Catholic variant on the scorched-earth Swedish Lutheranism of Ingmar Bergman's Winter Light; not a recipe for a breezy fun time at the movies, but when you're in the mood to really grapple, I mean, just grapple with religion and sociology and dense character acting, you could hardly find anything better in the contemporary cinema landscape.

Categories: irish cinema, very serious movies