Go east, young man

The Homesman is a film with an unimaginably specific and small ideal audience. It is, to begin with, a Western; a Western lover's Western, drunk on the iconography of the genre and steeped in an awareness of the kind of myths told in Western cinema and more than that, the particular language and tenor of those myths. It expects its viewer to know Westerns very well. Not a winning strategy in the 2010s. Meanwhile, it is also a film that holds the morality and conventions of the very same genre in open contempt: it regards the mythologising and wiry masculinity of the traditional Western with extreme distrust. That leaves basically nobody left to be fan of the thing, which is maybe why this terribly excellent film hit the ground stumbling at Cannes and has been greeted with muted positive reviews ever since. That, and the fact that it is unrelentingly bold in its experiments, and some of them don't land, and some of them only land if you're willing to buy into the film's ultimate thematic conclusion that basically sums up as: "fuck it, everything is hopeless". Which cuts into its target audience even more.

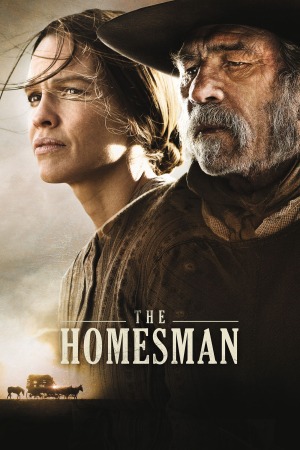

The second theatrical feature directed by Tommy Lee Jones (adapting the screenplay from Glendon Swarthout's novel alongside Kieran Fitzgerald & Wesley A. Oliver), and cementing him as an enormously interesting complicator of Western imagery, after his marvelous and horribly underrated The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, The Homesman is a film about madness. A specifically female variant of madness: once upon a time in the West, three women were broken down by the sheer oppressive agony of life in the Nebraska Territory, and the male-dominated culture that has managed to take root there. Arabella Sours (Grace Gummer) lost her children to diphtheria, Gro Svendson (Sonja Richter) was badly raped, and Theoline Belknap (Miranda Otto) just up and snapped from the sheer desolation of it all, and killed her child. All three of them have been left incapable of functioning in the merciless, survivalist world of the untamed West, and the community where they live has collectively decided to send them back East to Iowa, where a religious charity will tend to them. Only none of the men in the community can be bothered, and it falls to spinster Mary Bee Cuddy (Hilary Swank) to escort them all back to civilisation. Crossing paths with a pathetic claim jumper, George Briggs (Jones), Cuddy saves him from a lynching if and only if he'll act as guide and bodyguard.

That takes us around halfway through, which is before things get really peculiar, including a two-thirds twist that completely redirects the film's focus and energies, and is another reason why it's easy to hate the film; if you've been reading it as feminist up till that point (and there's no clear reason why you shouldn't), the twist comes as even more disruptive as a shock, since the film that happens afterwards can't be meaningfully defended as feminist on any level I'm familiar with. Except insofar as it goes to extreme lengths to look with dismay on the performance of masculinity in the context of the American West. Briggs, when we meet him, is a loathsome sad-sack, wheedling and messy and begging; over the course of his exposure to Cuddy, he tries very hard to become a better and more noble soul, and this ends up going nowhere at all. In its last scenes, the film adopts the perspective of late John Ford, the notion that the kind of unapologetic maledom that makes space for European civilisation to enter untamed wild spaces is itself totally unsuited for civilised people, and had better be regarded with cautious, pitying disgust than admiration. There is certainly nothing admirable about Briggs, except for little patches in the back half, and Jones's enthusiastic portrayal of all the character's faults is impressively free of any pride whatsoever.

But where Briggs is the prism through which the film refracts its ideas about morality and behavior in the West and thus, implicitly, in America itself (for what does the West function as in Westerns, if not a symbolic version of the country that rolled in after it?), The Homesman is not his movie. It's maybe not even Cuddy's movie, though you'd be forgiven for thinking that given the excellent precision of the writing and Swank's performance, which combine to make her one of the most singularly well-etched figures in English-language cinema in 2014. The film is really about those three madwomen, barely given lines of dialogue or individualising characteristics outside of the flashbacks that clarify what, exactly, drove them mad. Through all five of its central characters, the film is a pessimistic study of personally identity: how easily it can be broken, in the case of the three ill women; how conditional it is and subject to torment by the offhand cruelty of others, in the case of Cuddy; how powerless we can be to change it despite our best intentions, in the case of Briggs.

In short, it is a study of human, and especially feminine strength in the face of the bleakest hell of life imaginable. The West, as depicted in The Homesman, is a nasty and cruel place: Rodrigo Prieto's gorgeously severe cinematography, framing the horizon as prison that keeps the images pinned down, makes the New Mexican landscapes of the film shoot look beautiful and merciless; Marco Beltrami's score taps into traditional Western-style musical cues while bleaching them of all sentiment. It's a dry, bony film, always grappling in new and ever more eccentric ways with the limits and possibilities of human fortitude in the face of both physical and social cruelty.

Absolutely none of which successfully implies how captivating the whole of it is: impeccably acted, sharply written, and directed with a keen sense of both the power of visuals and the nuances of human behavior. It's not always free from being derivative - Ford's The Searchers and 7 Women are never far from mind, and its desire to probe its characters ends up leading it to some, odd, lumpy places (the last 15 minutes, in particular, are just damned confusing in the way they're assembled). But while it is a flawed film, they are glorious flaws; the flaws that come of trying to be as complicated and challenging as possible, to bend genre rules to one's own will, and to make an experience that genuinely interrogates itself and its audience. It's not always a totally satisfying experience, but it's one of the most engaging and rewarding films of the year even so.

9/10

The second theatrical feature directed by Tommy Lee Jones (adapting the screenplay from Glendon Swarthout's novel alongside Kieran Fitzgerald & Wesley A. Oliver), and cementing him as an enormously interesting complicator of Western imagery, after his marvelous and horribly underrated The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, The Homesman is a film about madness. A specifically female variant of madness: once upon a time in the West, three women were broken down by the sheer oppressive agony of life in the Nebraska Territory, and the male-dominated culture that has managed to take root there. Arabella Sours (Grace Gummer) lost her children to diphtheria, Gro Svendson (Sonja Richter) was badly raped, and Theoline Belknap (Miranda Otto) just up and snapped from the sheer desolation of it all, and killed her child. All three of them have been left incapable of functioning in the merciless, survivalist world of the untamed West, and the community where they live has collectively decided to send them back East to Iowa, where a religious charity will tend to them. Only none of the men in the community can be bothered, and it falls to spinster Mary Bee Cuddy (Hilary Swank) to escort them all back to civilisation. Crossing paths with a pathetic claim jumper, George Briggs (Jones), Cuddy saves him from a lynching if and only if he'll act as guide and bodyguard.

That takes us around halfway through, which is before things get really peculiar, including a two-thirds twist that completely redirects the film's focus and energies, and is another reason why it's easy to hate the film; if you've been reading it as feminist up till that point (and there's no clear reason why you shouldn't), the twist comes as even more disruptive as a shock, since the film that happens afterwards can't be meaningfully defended as feminist on any level I'm familiar with. Except insofar as it goes to extreme lengths to look with dismay on the performance of masculinity in the context of the American West. Briggs, when we meet him, is a loathsome sad-sack, wheedling and messy and begging; over the course of his exposure to Cuddy, he tries very hard to become a better and more noble soul, and this ends up going nowhere at all. In its last scenes, the film adopts the perspective of late John Ford, the notion that the kind of unapologetic maledom that makes space for European civilisation to enter untamed wild spaces is itself totally unsuited for civilised people, and had better be regarded with cautious, pitying disgust than admiration. There is certainly nothing admirable about Briggs, except for little patches in the back half, and Jones's enthusiastic portrayal of all the character's faults is impressively free of any pride whatsoever.

But where Briggs is the prism through which the film refracts its ideas about morality and behavior in the West and thus, implicitly, in America itself (for what does the West function as in Westerns, if not a symbolic version of the country that rolled in after it?), The Homesman is not his movie. It's maybe not even Cuddy's movie, though you'd be forgiven for thinking that given the excellent precision of the writing and Swank's performance, which combine to make her one of the most singularly well-etched figures in English-language cinema in 2014. The film is really about those three madwomen, barely given lines of dialogue or individualising characteristics outside of the flashbacks that clarify what, exactly, drove them mad. Through all five of its central characters, the film is a pessimistic study of personally identity: how easily it can be broken, in the case of the three ill women; how conditional it is and subject to torment by the offhand cruelty of others, in the case of Cuddy; how powerless we can be to change it despite our best intentions, in the case of Briggs.

In short, it is a study of human, and especially feminine strength in the face of the bleakest hell of life imaginable. The West, as depicted in The Homesman, is a nasty and cruel place: Rodrigo Prieto's gorgeously severe cinematography, framing the horizon as prison that keeps the images pinned down, makes the New Mexican landscapes of the film shoot look beautiful and merciless; Marco Beltrami's score taps into traditional Western-style musical cues while bleaching them of all sentiment. It's a dry, bony film, always grappling in new and ever more eccentric ways with the limits and possibilities of human fortitude in the face of both physical and social cruelty.

Absolutely none of which successfully implies how captivating the whole of it is: impeccably acted, sharply written, and directed with a keen sense of both the power of visuals and the nuances of human behavior. It's not always free from being derivative - Ford's The Searchers and 7 Women are never far from mind, and its desire to probe its characters ends up leading it to some, odd, lumpy places (the last 15 minutes, in particular, are just damned confusing in the way they're assembled). But while it is a flawed film, they are glorious flaws; the flaws that come of trying to be as complicated and challenging as possible, to bend genre rules to one's own will, and to make an experience that genuinely interrogates itself and its audience. It's not always a totally satisfying experience, but it's one of the most engaging and rewarding films of the year even so.

9/10

Categories: fun with structure, gorgeous cinematography, travelogues, westerns