Out of sight

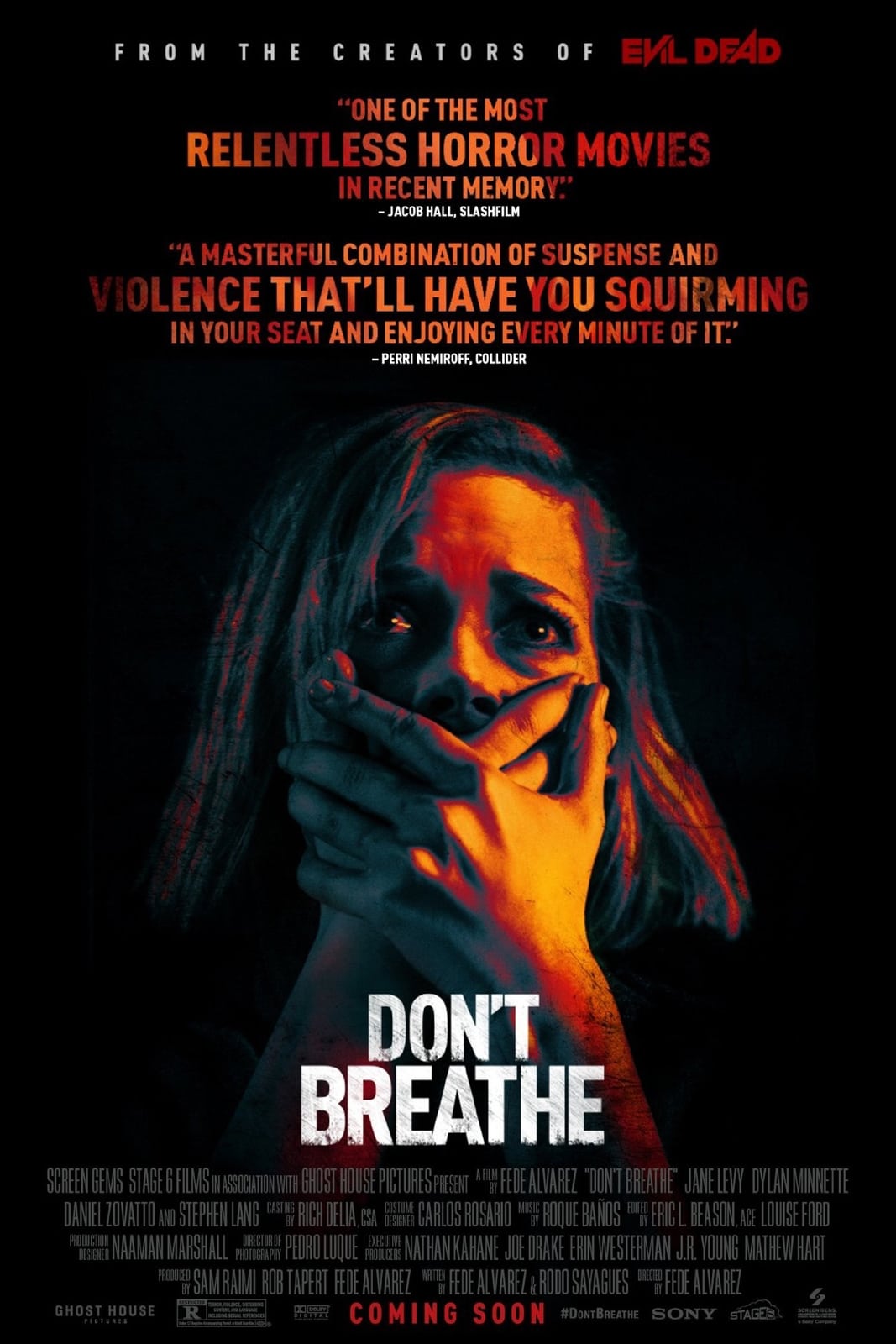

Fundamentally, the only thing that Don't Breathe gets wrong is that is has the wrong protagonists. Or maybe it's even that it has the right protagonists, but doesn't know what to properly do with them. So much of the film feels like it should be a perfectly engaging bit of end-of-summer tosh, a shabby little shocker of, if not the first order, then comfortably the second. Fede Alvarez's direction is more pointed and confident than when he proficiently and indifferently remade Evil Dead back in 2013; if nothing else, he's absolutely perfectly nailed the mixture of rhythms - from cautious, low-boil tension to shrieking terror and then back again - that go into making this sort of thriller work. And while the film's visual design is every bit as full of convenient holes as its plot (my goodness, but this movie's blind man does like to leave random lamps turned on in the corner of rooms at 2:30 in the morning), the sense of a creepy haunted house drawn from the most unexceptional sort of suburban residential architecture services the film enormously well. Then you get to the script that Alvarez wrote with Rodo Sayagues, and you discover what kind of protagonist they're trying to pass off on us, and it's just the most deflating thing. Hard to appreciate a mercilessly slow build of tension when you spend half of the movie muttering to yourself "for God's sake, why haven't these fuckers died yet?" Not since Frozen - not that one - have I encountered such a good-in-most-ways thriller that broke apart completely as a result of forcing me to spend time with people who so little deserved my sympathy.

We'll return to that, but for now, the plot: in Detroit, that city which most pithily sums up the idea of post-industrial poverty in the United States, there are many desperately poor people, but we for the moment chiefly care about three. These are Alex (Dylan Minnette), Roxanne AKA Rocky (Jane Levy), and Money (Daniel Zovatto), which is also an AKA, I suppose, but we never learn for what (incidentally, two of these people are white and one is Latino, which isn't exactly what the phrase "the miserable poor of Detroit" calls to mind, but movie industry gonna movie industry). They are house robbers, breaking their way into the homes of the extraordinarily rich thanks to Alex's father's job at a home security firm; apparently his job involves bringing home his keys that unlock everything in the world and deactivate the alarm systems his company installs, and then leaving them in unsecured locations, which is the first time the movie dragged a reluctant "...well, if that's actually going to be the premise, I'll let you have it" out of me. Anyway, we quickly learn about our three brigands that Money is the outright sociopath, breaking shit and pissing on stuff; Alex, who nervously recites legal factoids to the others (most pertinently, that as long as they keep their takings to under $10,000 per house, they aren't technically felons); and Rocky is the one who is Just Doing It For Her Daughter. Sister? Gotta Be Daughter. The relationship between her, and little Diddy (Emma Bercovici), and her nightmare of a mother (Katia Bokor) only really makes sense if Rocky is Diddy's mother, but very, very late in the movie, we have it confirmed that these ragged-looking twentysomethings are in fact just teenagers. Which is a development that legitimately costs the movie a whole hell of a lot: young adults driven to crimes and bad decisions out of economic want have a wholly different tragic dimension than teenagers doing the same.

Anyway, Money's fence lets him in on a secret, way out on the edge of town, where nobody lives, there's one solitary inhabited house, and the owner of that house once received hundreds of thousands of dollars in a settlement when a rich teen girl ran over his daughter and killed her. With proper justice denied, the old man had to settle for money that he apparently didn't want, or at least hasn't visibly spent; he still lives in a rundown shithole, and his only apparently expenditure of late has been to trick out his house with security from Alex's dad's company. Money and Rocky enthusiastically decide to rip him off, and Alex is wrangled into thanks to his unspoken but super-obvious crush on Rocky. While they're observing the man (Stephen Lang), they discover that he's blind, a victim of the first Iraq War; this is almost enough to completely rattle Alex, but he's still stuck thinking with his dick, and it doesn't even give Rocky and Money pause to think that they're about to steal the whole net worth of a blind man whose sole loved one was brutally taken away thanks to the mindless indulgence of an entitled upper class idiot. Our heroes!

I mean literally, our heroes. The film knows that Money is a greedy prick, to its credit, but it genuinely seems to think that Rocky's motives to take Diddy away to Los Angeles obviate her choices, and Alex's forthright guilt does the same for him. As a result, I hated both of them much more: Rocky especially, given the needless way that the movie keeps making her reiterate her bad choices. At one point, somewhat more than midway through, there is a point where they can abandon the money and escape reasonably intact and safe, and she goes out of her way to decide that she's not going to do that. If I hadn't mostly loathed her before then, I surely would have after. It doesn't help that Levy's and especially Minnette's performances are both pretty mildewy and whinging; if any little bit of sympathy had managed to accrue to the protagonists, their watery facial expressions and shrill line deliveries would surely have done it in.

The thing is, Don't Breathe is a horror film and a thriller, but mostly it is a thriller. This means something very specifically important in this case. If this were, say, a slasher movie, it wouldn't matter if the "good guys" were awful. In that kind of horror picture, the real protagonist is the killings themselves and the make-up effects used to execute them; having unlikable victims is, indeed, part of the charm, since we are secretly hoping they die in robust ways. Or not so secretly. But in a thriller of this stripe, we need, somewhat, to feel sorry for the victims: we are meant to be able to inhabit their situation and feel empathetically what they feel. We can't root for their deaths, because the entire effect of the movie hinges on the question: "what if that were me?" If it were me, I pray that I would not be a repulsive asshole - a hypocritical repulsive asshole, in Alex's case. And mind you, in the real world, being kind of needlessly obnoxious and stealing from a man who's really no better off than they are wouldn't earn the characters the ghastly things that happen to them - but in the karmic universe of a genre film, they get just what they've earned.

There could be something in here: the story of a blind man with a unique set of skills turning the tables on his idiot teen assailants, only told from the other side. But grasping, perhaps, that they've left the villain of the piece as the more inherently sympathetic figure (and Lang's performance, outclassing everybody else in the movie by margins that I almost can't even get my head around, makes him something close to a tearful Lear figure, making it even harder to root against him in this context), even as he uses his military training to rather effortlessly take the teens down, Alvarez & Sayagues turn him into some kind of psychopathic super-monster; I will not say how or what, other than that it's too crass for the straitlaced, mostly realistic tone of the movie, and not nearly crass enough to transform it into ripping good exploitation. Anyway, the film enters a moral dead zone: ludicriously evil bad guy versus pointlessly unlikable leads. Who could definitely have been made likable, but no matter. It leaves the film a perfectly-tuned, well-oiled machine without an engine: this kind of thriller simply can't function as a pure exercise in craft, it needs someone for us to feel for, and it lacks that, and so there's nothing to do but admire, in an empty way, what Alvarez and his crew have accomplished.

By all means! Let us so admire! The assembly of the film's visual elements leaves very little to be desired: especially Pedro Luque's choking, underlit cinematography, which sets off Naaman Marshall's wonderful production design. The blind man's home undoubtedly comes across as much too spacious and elaborately laid-out for a stock bungalow in a run-down part of Detroit - and the basement, where much of the most important action takes place, is easily four times bigger than it has any sane right to be - but it serves well as a creepy movie set full of appropriately secretive hidey-holes for the blind man to pop out of, doing his absolute best Teleporting Killer routine. And the sound design is, genuinely, superlative stuff: many of the sounds are unreasonably loud and given grating, jarring timbre, exaggerated and heightened in a horror movie elaboration of the way that sounds magnify when everything is unnaturally silent. Everything about the film works, except for the fact that it just plain doesn't work at all. 'Tis pity that such a well-honed thriller should take place around such a vacuous center.

We'll return to that, but for now, the plot: in Detroit, that city which most pithily sums up the idea of post-industrial poverty in the United States, there are many desperately poor people, but we for the moment chiefly care about three. These are Alex (Dylan Minnette), Roxanne AKA Rocky (Jane Levy), and Money (Daniel Zovatto), which is also an AKA, I suppose, but we never learn for what (incidentally, two of these people are white and one is Latino, which isn't exactly what the phrase "the miserable poor of Detroit" calls to mind, but movie industry gonna movie industry). They are house robbers, breaking their way into the homes of the extraordinarily rich thanks to Alex's father's job at a home security firm; apparently his job involves bringing home his keys that unlock everything in the world and deactivate the alarm systems his company installs, and then leaving them in unsecured locations, which is the first time the movie dragged a reluctant "...well, if that's actually going to be the premise, I'll let you have it" out of me. Anyway, we quickly learn about our three brigands that Money is the outright sociopath, breaking shit and pissing on stuff; Alex, who nervously recites legal factoids to the others (most pertinently, that as long as they keep their takings to under $10,000 per house, they aren't technically felons); and Rocky is the one who is Just Doing It For Her Daughter. Sister? Gotta Be Daughter. The relationship between her, and little Diddy (Emma Bercovici), and her nightmare of a mother (Katia Bokor) only really makes sense if Rocky is Diddy's mother, but very, very late in the movie, we have it confirmed that these ragged-looking twentysomethings are in fact just teenagers. Which is a development that legitimately costs the movie a whole hell of a lot: young adults driven to crimes and bad decisions out of economic want have a wholly different tragic dimension than teenagers doing the same.

Anyway, Money's fence lets him in on a secret, way out on the edge of town, where nobody lives, there's one solitary inhabited house, and the owner of that house once received hundreds of thousands of dollars in a settlement when a rich teen girl ran over his daughter and killed her. With proper justice denied, the old man had to settle for money that he apparently didn't want, or at least hasn't visibly spent; he still lives in a rundown shithole, and his only apparently expenditure of late has been to trick out his house with security from Alex's dad's company. Money and Rocky enthusiastically decide to rip him off, and Alex is wrangled into thanks to his unspoken but super-obvious crush on Rocky. While they're observing the man (Stephen Lang), they discover that he's blind, a victim of the first Iraq War; this is almost enough to completely rattle Alex, but he's still stuck thinking with his dick, and it doesn't even give Rocky and Money pause to think that they're about to steal the whole net worth of a blind man whose sole loved one was brutally taken away thanks to the mindless indulgence of an entitled upper class idiot. Our heroes!

I mean literally, our heroes. The film knows that Money is a greedy prick, to its credit, but it genuinely seems to think that Rocky's motives to take Diddy away to Los Angeles obviate her choices, and Alex's forthright guilt does the same for him. As a result, I hated both of them much more: Rocky especially, given the needless way that the movie keeps making her reiterate her bad choices. At one point, somewhat more than midway through, there is a point where they can abandon the money and escape reasonably intact and safe, and she goes out of her way to decide that she's not going to do that. If I hadn't mostly loathed her before then, I surely would have after. It doesn't help that Levy's and especially Minnette's performances are both pretty mildewy and whinging; if any little bit of sympathy had managed to accrue to the protagonists, their watery facial expressions and shrill line deliveries would surely have done it in.

The thing is, Don't Breathe is a horror film and a thriller, but mostly it is a thriller. This means something very specifically important in this case. If this were, say, a slasher movie, it wouldn't matter if the "good guys" were awful. In that kind of horror picture, the real protagonist is the killings themselves and the make-up effects used to execute them; having unlikable victims is, indeed, part of the charm, since we are secretly hoping they die in robust ways. Or not so secretly. But in a thriller of this stripe, we need, somewhat, to feel sorry for the victims: we are meant to be able to inhabit their situation and feel empathetically what they feel. We can't root for their deaths, because the entire effect of the movie hinges on the question: "what if that were me?" If it were me, I pray that I would not be a repulsive asshole - a hypocritical repulsive asshole, in Alex's case. And mind you, in the real world, being kind of needlessly obnoxious and stealing from a man who's really no better off than they are wouldn't earn the characters the ghastly things that happen to them - but in the karmic universe of a genre film, they get just what they've earned.

There could be something in here: the story of a blind man with a unique set of skills turning the tables on his idiot teen assailants, only told from the other side. But grasping, perhaps, that they've left the villain of the piece as the more inherently sympathetic figure (and Lang's performance, outclassing everybody else in the movie by margins that I almost can't even get my head around, makes him something close to a tearful Lear figure, making it even harder to root against him in this context), even as he uses his military training to rather effortlessly take the teens down, Alvarez & Sayagues turn him into some kind of psychopathic super-monster; I will not say how or what, other than that it's too crass for the straitlaced, mostly realistic tone of the movie, and not nearly crass enough to transform it into ripping good exploitation. Anyway, the film enters a moral dead zone: ludicriously evil bad guy versus pointlessly unlikable leads. Who could definitely have been made likable, but no matter. It leaves the film a perfectly-tuned, well-oiled machine without an engine: this kind of thriller simply can't function as a pure exercise in craft, it needs someone for us to feel for, and it lacks that, and so there's nothing to do but admire, in an empty way, what Alvarez and his crew have accomplished.

By all means! Let us so admire! The assembly of the film's visual elements leaves very little to be desired: especially Pedro Luque's choking, underlit cinematography, which sets off Naaman Marshall's wonderful production design. The blind man's home undoubtedly comes across as much too spacious and elaborately laid-out for a stock bungalow in a run-down part of Detroit - and the basement, where much of the most important action takes place, is easily four times bigger than it has any sane right to be - but it serves well as a creepy movie set full of appropriately secretive hidey-holes for the blind man to pop out of, doing his absolute best Teleporting Killer routine. And the sound design is, genuinely, superlative stuff: many of the sounds are unreasonably loud and given grating, jarring timbre, exaggerated and heightened in a horror movie elaboration of the way that sounds magnify when everything is unnaturally silent. Everything about the film works, except for the fact that it just plain doesn't work at all. 'Tis pity that such a well-honed thriller should take place around such a vacuous center.

Categories: horror, summer movies, thrillers