Walking about

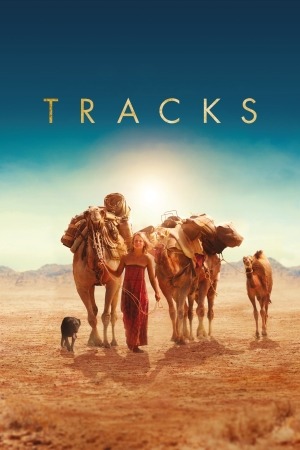

In 1977, 27-year-old Robyn Davidson walked from Alice Springs, Australia, to the west coast of that country, a 2700-kilometer hike primarily through desert that took nine months. The trip was financed by National Geographic out of the United States, which published an article written by Davidson the year following her journey, and filmmakers have been trying to tell her story ever since (more precisely, ever since her 1980 memoir, Tracks). And now they have finally succeeded, with a film also called Tracks, starring Mia Wasikowska as Davidson - an actress whose lifespan is shorter than the story's time in Development Hell.

Was it worth the wait? Probably. The story is very worth the telling, though Tracks the movie is not, I suspect, the best telling it could have received. It doesn't have the same messiness that plagues the awfully similar American film Wild (which premiered at Telluride one year to the day later than Tracks's bow at the 2013 Venice Film Festival), but only because it lacks Wild's go-for-broke ambition. Tracks is a lovely little film - very literally lovely. Director John Curran and cinematographer Mandy Walker have framed the Outback with one heartstopping postcard-ready frame after another, emphasising the hard orange ground and the empty pale-blue sky as the totality of Robyn's world, gorgeous but also devoid of anything that allows human beings to interact with it. Of course, the Australian Outback is just one of those landscapes: if you can't make it look extravagantly beautiful in endless anamorphic widescreen vistas like the ones Tracks has, they take away your right to be a cinematographer, I'm pretty sure. But Australia native Walker has been here before (she shot Baz Luhrmann's Australia, for starters), and while she is primarily interested in making Tracks gorgeous, she's not only interested in that. Which counts for a hell of a lot.

The point being, Tracks looks as picturesquely desolate as you could ever hope for, which cuts both ways. On the one hand, it sure does look like the kind of landscape that you would not want to walk through, if you had any plans of not dying from thirst. On the other hand, it's the most obvious manifestation of a problem that kicks in the second that Robyn starts her walk and doesn't let up for a solid half of the film's overall running time: the film does a terrible job of making her walk seem all that arduous or dangerous. Obstacles come up, the kind that in real life could have easily resulted in Davidson's real-life death if she hadn't kept her wits about her and taken quick, decisive action. But in the movie, that's all they seem to be: obstacles. Not even very daunting ones, just kind of like petty annoyances that just have to be cleared out, sigh, why do these things happen to me in the middle of the most isolated corner of God's earth, populated by the nastiest, most deadly fauna ever bred in the pits of hell?

Only late in the film, well over 100 days into the journey, does the toll of the desert start to wear on the character Robyn, and that's not even because of the walking itself; it's because she finally got caught by the past she's been trying to keep ahead of (presented in a terribly shovey flashback, thankfully a device that the film mostly avoids), in the process of having to make a hard but necessary choice that would be all sorts of spoilers to bring it up. It means that the film ends far more effectively than it middles, but by then it's too little, too late.

Not that Tracks is a waste, or anything like that at all. It ends well; so does it begin well, not with Robyn's first steps into the wild, but a full half-hour detailing her lengthy, years-long planning, in which she gathered information and knowledge in the delicate art of handling camels, four of which follow her as pack animals during her otherwise isolated trek. We meet the usual collection of sharply-etched colorful locals from movies set in rural Australia, and the American photographer assigned by National Geographic to bother Robyn, Rick Smolan (Adam Driver), who the film teases as a romantic partner before real life obliges it to abandon that thread around midway through. And we get to bask in the best of Wasikowska's terrifically strong performance, when she is an immovable object steadily hewing to her plans in the face of every single person she meets besides Rick finding it odd and inexplicable, rather than doing so in the face of lots of desert. With the film steadily refusing to supply overt reasons for what she's doing, Waskikowska's Robyn has to seem strong and determined and prideful and resilient as qualities solely in reference to themselves, without coming off like some sort of robot acting according to the arbitrary whims of the scenario, and this she does marvelously well; without being permitted to open up a woman who is very clearly disinterested in letting us or any of the other characters psychoanalyze her, Wasikowska still manages to create a totally engaging and relatable protagonist.

Which is pretty much all that Tracks is interested in, ultimately. Marion Nelson's screenplay and Curran's directing alike are flatly presentational: "this happened, in roughly this way, and isn't that absolutely fascinating?" is pretty much the entirety of the film's editorial viewpoint. Nor does the filmmaking push any harder; some intriguingly aggressive close-ups and a few daring cuts to elide time are absolutely the only things challenging about it in any way. It has a story to tell and it tells it, with neither fuss nor much digging into the marrow of that story. There's something appealing to that kind of clarity and total lack of pretension, but it leaves us without all that much in the way of memorable cinema; if Tracks had anything in it to match Wasikowska's performance, we might have a real movie to pass down through the years, instead of something that's solid entertainment the one and probably only time ever you watch it.

7/10

Was it worth the wait? Probably. The story is very worth the telling, though Tracks the movie is not, I suspect, the best telling it could have received. It doesn't have the same messiness that plagues the awfully similar American film Wild (which premiered at Telluride one year to the day later than Tracks's bow at the 2013 Venice Film Festival), but only because it lacks Wild's go-for-broke ambition. Tracks is a lovely little film - very literally lovely. Director John Curran and cinematographer Mandy Walker have framed the Outback with one heartstopping postcard-ready frame after another, emphasising the hard orange ground and the empty pale-blue sky as the totality of Robyn's world, gorgeous but also devoid of anything that allows human beings to interact with it. Of course, the Australian Outback is just one of those landscapes: if you can't make it look extravagantly beautiful in endless anamorphic widescreen vistas like the ones Tracks has, they take away your right to be a cinematographer, I'm pretty sure. But Australia native Walker has been here before (she shot Baz Luhrmann's Australia, for starters), and while she is primarily interested in making Tracks gorgeous, she's not only interested in that. Which counts for a hell of a lot.

The point being, Tracks looks as picturesquely desolate as you could ever hope for, which cuts both ways. On the one hand, it sure does look like the kind of landscape that you would not want to walk through, if you had any plans of not dying from thirst. On the other hand, it's the most obvious manifestation of a problem that kicks in the second that Robyn starts her walk and doesn't let up for a solid half of the film's overall running time: the film does a terrible job of making her walk seem all that arduous or dangerous. Obstacles come up, the kind that in real life could have easily resulted in Davidson's real-life death if she hadn't kept her wits about her and taken quick, decisive action. But in the movie, that's all they seem to be: obstacles. Not even very daunting ones, just kind of like petty annoyances that just have to be cleared out, sigh, why do these things happen to me in the middle of the most isolated corner of God's earth, populated by the nastiest, most deadly fauna ever bred in the pits of hell?

Only late in the film, well over 100 days into the journey, does the toll of the desert start to wear on the character Robyn, and that's not even because of the walking itself; it's because she finally got caught by the past she's been trying to keep ahead of (presented in a terribly shovey flashback, thankfully a device that the film mostly avoids), in the process of having to make a hard but necessary choice that would be all sorts of spoilers to bring it up. It means that the film ends far more effectively than it middles, but by then it's too little, too late.

Not that Tracks is a waste, or anything like that at all. It ends well; so does it begin well, not with Robyn's first steps into the wild, but a full half-hour detailing her lengthy, years-long planning, in which she gathered information and knowledge in the delicate art of handling camels, four of which follow her as pack animals during her otherwise isolated trek. We meet the usual collection of sharply-etched colorful locals from movies set in rural Australia, and the American photographer assigned by National Geographic to bother Robyn, Rick Smolan (Adam Driver), who the film teases as a romantic partner before real life obliges it to abandon that thread around midway through. And we get to bask in the best of Wasikowska's terrifically strong performance, when she is an immovable object steadily hewing to her plans in the face of every single person she meets besides Rick finding it odd and inexplicable, rather than doing so in the face of lots of desert. With the film steadily refusing to supply overt reasons for what she's doing, Waskikowska's Robyn has to seem strong and determined and prideful and resilient as qualities solely in reference to themselves, without coming off like some sort of robot acting according to the arbitrary whims of the scenario, and this she does marvelously well; without being permitted to open up a woman who is very clearly disinterested in letting us or any of the other characters psychoanalyze her, Wasikowska still manages to create a totally engaging and relatable protagonist.

Which is pretty much all that Tracks is interested in, ultimately. Marion Nelson's screenplay and Curran's directing alike are flatly presentational: "this happened, in roughly this way, and isn't that absolutely fascinating?" is pretty much the entirety of the film's editorial viewpoint. Nor does the filmmaking push any harder; some intriguingly aggressive close-ups and a few daring cuts to elide time are absolutely the only things challenging about it in any way. It has a story to tell and it tells it, with neither fuss nor much digging into the marrow of that story. There's something appealing to that kind of clarity and total lack of pretension, but it leaves us without all that much in the way of memorable cinema; if Tracks had anything in it to match Wasikowska's performance, we might have a real movie to pass down through the years, instead of something that's solid entertainment the one and probably only time ever you watch it.

7/10

Categories: gorgeous cinematography, oz/kiwi cinema, the dread biopic