Cinderellas Who Have Gone Before: This lovely night was only a fantasy

The Slipper and the Rose: The Story of Cinderella is, to begin with, an absurd anachronism. For anyone in the English-speaking world to try to put over an overlong spectacle-driven megamusical in 1976 was psychotic - the last hit film on that model was the five-year-old Fiddler on the Roof, and that was itself clearly already an aberration, two years after the very visible implosion of Paint Your Wagon and Hello, Dolly! - and The Slipper and the Rose didn't even have the advantage of being an adaptation of an established show. Though the cinematography is pure mid-'70s, everything else about the film is unreservedly old-fashioned. This is, in honesty, the primary locus of its charm: the clear sense, even some four decades after its creation, that this is all a bit hokey and warmly conservative, and it simply doesn't care what we think about that. It's too busy putting on a show in the most enormous, sloppy, ridiculous way. It is the movie version of a St. Bernard that just lumbers right on over and clambers up on your lap to lick your face.

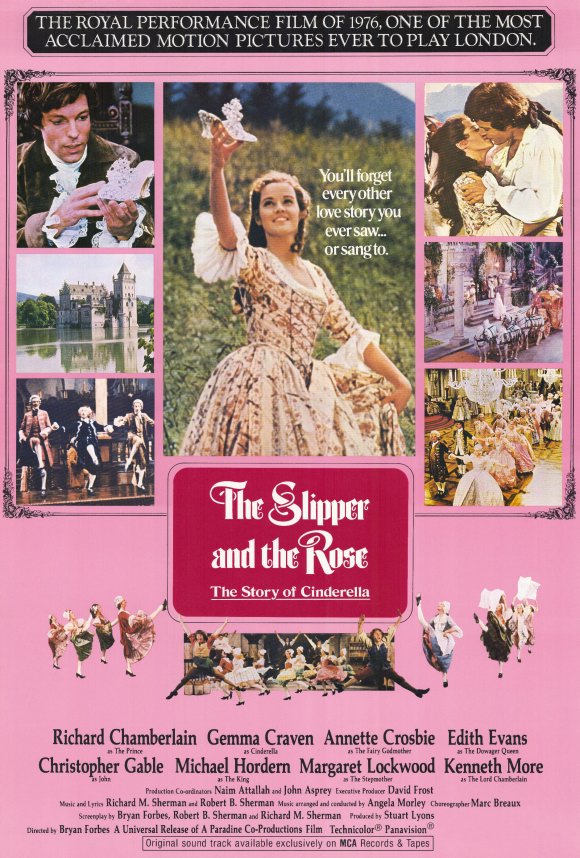

The updated version of the classic fairy tale, written by brothers Robert M. Sherman and Richard B. Sherman, with some polishing done by Bryan Forbes - the former pair provided the film's soundtrack, the latter its direction - takes place in the 18th Century in a particularly British Ruritanian kingdom by the name of Euphrania. Here, the sturdy but easily rattled king (Michael Hordern) is busily trying to marry off his sole child, Prince Edward (Richard Chamberlain), but Edward has a rather snide disdain for the looks of the (presumably inbred) princesses his father has been sending him off to visit, and roughly declares that he'd rather marry for love than political convenience. This baffles or offends the whole court: his father and mother (Lally Bowers) have been tremendously happy in their arranged marriage, and, they, along with the Lord Chamberlain (Kenneth More) and the batty queen mother (Dame Edith Evans, in the last of her screen roles released during her life) loudly try to sing him down. The only person on his side is his valet and best friend, John (Christopher Gable), who knows the same pain: he's in love with a woman far above his station, whom he can never marry.

You know, the basic meat and potatoes of the Cinderella fairy tale.

After 19 minutes and two songs, we do finally meet Cinderella (Gemma Craven), returning from her father's funeral to learn that her stepmother (Margaret Lockwood, in her own final screen role, though she'd live another 14 years) and gorgeous but cruel stepsisters (Rosalind Ayres and Sherrie Hewson) are exploiting the letter of the dead man's will, though by no means the spirit, to rob Cinderella of her birthright and leave her at the status of unpaid housekeeper. This happens just before the king irritably announces a ball which is to find every woman of the nobility lining up to be thrown at the prince in a last-ditch effort to make him interested in anybody besides John. And the rest you know: Cinderella is aided by a curious woman (Annette Crosbie) who uses magic to help the girl in her chores, and eventually to attend the ball herself. She and the prince fall in love, she runs away, he hunts through the kingdom for her, we all leave happy.

Or, you know, not that. The film gave away the game by waiting so long to introduce its nominal protagonist: this version of the story is, weirdly, more interested with family-friendly court intrigue and the annoyances of dynastic politics than it is with fairy tale princesses. And so, after the ball is over, there's almost a solid hour of movie left that decides, inexplicably, to roll a whole theme of class bigotry into the story, and send Cinderella into willing exile so that Edward will marry for the best good of the kingdom. And all this realpolitik is, I want to point out, in the context of a story that also witnesses a magical woman turn ballet dancing mice into horses

It's different, anyway. And mostly, it's different in ways that demonstrate just how little actually happens in Charles Perrault's Cinderella that qualifies as drama. Even with its puffy opening sequence, the main part of The Slipper and the Rose still only gets us to about 80 minutes or so, out of an indefensibly indulgent 143 minute running time (the original U.S. release of this British production cut that down by 16 minutes: two songs - two of the better songs, actually - and some cute but largely irrelevant business for the fairy godmother). It's fascinatingly wrong-headed: this isn't a case of too much story stapled to a slender frame, it's a case of even the added story proving insufficient to hoist the running time up, so the filmmakers kept adding new wrinkles out of nowhere. It doesn't feel like a 143-minute film that got there through a lack of discipline and trimming; it feels like they wanted it to be 143 minutes, and kept adding acts till it got there.

That being said, for that first hour and twenty minutes, The Slipper and the Rose is a genuinely charming and likable variant on the well-told tale. The focus on the sullen prince and the desperate king is a weird shift, absolutely, but it draws attention away from how thoroughly dull Cinderella is in the source material and every traditional adaptation thereof. Some of the individual tweaks are even clever: e.g. the expanded role for the fairy godmother as a general helper sets up the mid-film twist that she's used up too much magic on Cinderella's behalf, and has to borrow more than her share to set up her goddaughter for the ball; hence the otherwise arbitrary midnight cutoff, which represents all the extra magic she was able to scrounge up. And any depiction in any Cinderella story of the stepsisters as attractive and fashionable helps to cushion the material's deeply broken notions of femininity.

Mostly, though, what works is the filmmaking itself, rather than the storytelling. Bryan Forbes was a better director than this project deserved, frankly, and he puts a lot more care into it than it needed. The film has an odd but totally effective addiction to wide shots: Forbes and cinematographer Tony Imi use the full scale of the anamorphic frame to present crowd shots and big interior spaces, adding a distinct sense of grandeur and scale to the film; mixed with the '70s-style naturalism of the lighting and focus, it's physically present in a way that belies the general '60s superproduction tenor of most of what's going on otherwise. By stressing wide shots and using close-ups only as very conscious punction, the filmmakers emphasise the world of the story, rather like the script's attention to politicking over fairytale lovemaking. And the design team certainly built up a world worth emphasising: Raymond Simm's sets are plausible enough that the fantasy and fluffiness don't float away into the ether, but it's Julie Harris's costumes that really dominate the film. They rush right up to the edge of gaudy: the ball scenes resembling nothing as much as the carefully choreographed dancing of a display case of brightly-iced cupcakes. But that same sugar-sweet fanciness is entirely beguiling at the level of glossy fable; and this is, after all, Cinderella.

Beyond the look of the thing, the film enjoys a pretty terrific cast; with a blank role to play, Craven can't do much, but it's not her film. This movie belongs entirely to the grown-ups: the icy but still human Lockwood, the sputtering, lovable Hordern, the calm and stern Bowers, and chiefly and above all Evans, who plays the most generic role imaginable - the old lady has no idea what's going on, har har - but does so with the most infectious possible brio. It's caricature at it's absolute best, and Evans's performance is the most effortless kind of scene-stealing.

Really, the performances and style are so good that even with the leaden final hour, The Slipper and the Rose could still sparkle; the only thing holding it down to the level of generally charming trifle that's far more boring than it has any cause to be is, I hate to say, the songs by the Sherman brothers. So many delectable scores for Disney came out of those two minds! And yet the 12 songs here are pretty much just one banality after another: perfectly serviceable tunes matched to lyrics that are infinitely clever and proud of their twisty wordplay, without being actually funny; the love ballads are at least a touch more concrete than the prattle-heavy comic numbers, but they're also a bit treacly. Either way, the songs come off as a bit strained and brittle, and they're derivative in obvious ways from the Shermans' earlier, better-known, and just plain stronger songs: it doesn't help that the odd "well, let's go ahead and talk about the class struggle" tune "Position and Positioning" steals its choreography straight from "Step In Time" from Mary Poppins, in case anybody had made it that far into the film without flashing back to the Shermans' most iconic musical.

Snip out the songs, though, and The Slipper and the Rose is a cutely off-kilter riff on a familiar story, with just enough peculiar fascination with the unexplored ramifications of that story to feel like its own thing. Obviously, "snip out the songs" is about as bad a thing as anybody could say about a feature-length musical; but the vivid craftsmanship and thoroughly delightful character acting is enough to make a surprisingly enjoyable experience out of the film, even as it fails what theoretically ought to be its most basic test.

The updated version of the classic fairy tale, written by brothers Robert M. Sherman and Richard B. Sherman, with some polishing done by Bryan Forbes - the former pair provided the film's soundtrack, the latter its direction - takes place in the 18th Century in a particularly British Ruritanian kingdom by the name of Euphrania. Here, the sturdy but easily rattled king (Michael Hordern) is busily trying to marry off his sole child, Prince Edward (Richard Chamberlain), but Edward has a rather snide disdain for the looks of the (presumably inbred) princesses his father has been sending him off to visit, and roughly declares that he'd rather marry for love than political convenience. This baffles or offends the whole court: his father and mother (Lally Bowers) have been tremendously happy in their arranged marriage, and, they, along with the Lord Chamberlain (Kenneth More) and the batty queen mother (Dame Edith Evans, in the last of her screen roles released during her life) loudly try to sing him down. The only person on his side is his valet and best friend, John (Christopher Gable), who knows the same pain: he's in love with a woman far above his station, whom he can never marry.

You know, the basic meat and potatoes of the Cinderella fairy tale.

After 19 minutes and two songs, we do finally meet Cinderella (Gemma Craven), returning from her father's funeral to learn that her stepmother (Margaret Lockwood, in her own final screen role, though she'd live another 14 years) and gorgeous but cruel stepsisters (Rosalind Ayres and Sherrie Hewson) are exploiting the letter of the dead man's will, though by no means the spirit, to rob Cinderella of her birthright and leave her at the status of unpaid housekeeper. This happens just before the king irritably announces a ball which is to find every woman of the nobility lining up to be thrown at the prince in a last-ditch effort to make him interested in anybody besides John. And the rest you know: Cinderella is aided by a curious woman (Annette Crosbie) who uses magic to help the girl in her chores, and eventually to attend the ball herself. She and the prince fall in love, she runs away, he hunts through the kingdom for her, we all leave happy.

Or, you know, not that. The film gave away the game by waiting so long to introduce its nominal protagonist: this version of the story is, weirdly, more interested with family-friendly court intrigue and the annoyances of dynastic politics than it is with fairy tale princesses. And so, after the ball is over, there's almost a solid hour of movie left that decides, inexplicably, to roll a whole theme of class bigotry into the story, and send Cinderella into willing exile so that Edward will marry for the best good of the kingdom. And all this realpolitik is, I want to point out, in the context of a story that also witnesses a magical woman turn ballet dancing mice into horses

It's different, anyway. And mostly, it's different in ways that demonstrate just how little actually happens in Charles Perrault's Cinderella that qualifies as drama. Even with its puffy opening sequence, the main part of The Slipper and the Rose still only gets us to about 80 minutes or so, out of an indefensibly indulgent 143 minute running time (the original U.S. release of this British production cut that down by 16 minutes: two songs - two of the better songs, actually - and some cute but largely irrelevant business for the fairy godmother). It's fascinatingly wrong-headed: this isn't a case of too much story stapled to a slender frame, it's a case of even the added story proving insufficient to hoist the running time up, so the filmmakers kept adding new wrinkles out of nowhere. It doesn't feel like a 143-minute film that got there through a lack of discipline and trimming; it feels like they wanted it to be 143 minutes, and kept adding acts till it got there.

That being said, for that first hour and twenty minutes, The Slipper and the Rose is a genuinely charming and likable variant on the well-told tale. The focus on the sullen prince and the desperate king is a weird shift, absolutely, but it draws attention away from how thoroughly dull Cinderella is in the source material and every traditional adaptation thereof. Some of the individual tweaks are even clever: e.g. the expanded role for the fairy godmother as a general helper sets up the mid-film twist that she's used up too much magic on Cinderella's behalf, and has to borrow more than her share to set up her goddaughter for the ball; hence the otherwise arbitrary midnight cutoff, which represents all the extra magic she was able to scrounge up. And any depiction in any Cinderella story of the stepsisters as attractive and fashionable helps to cushion the material's deeply broken notions of femininity.

Mostly, though, what works is the filmmaking itself, rather than the storytelling. Bryan Forbes was a better director than this project deserved, frankly, and he puts a lot more care into it than it needed. The film has an odd but totally effective addiction to wide shots: Forbes and cinematographer Tony Imi use the full scale of the anamorphic frame to present crowd shots and big interior spaces, adding a distinct sense of grandeur and scale to the film; mixed with the '70s-style naturalism of the lighting and focus, it's physically present in a way that belies the general '60s superproduction tenor of most of what's going on otherwise. By stressing wide shots and using close-ups only as very conscious punction, the filmmakers emphasise the world of the story, rather like the script's attention to politicking over fairytale lovemaking. And the design team certainly built up a world worth emphasising: Raymond Simm's sets are plausible enough that the fantasy and fluffiness don't float away into the ether, but it's Julie Harris's costumes that really dominate the film. They rush right up to the edge of gaudy: the ball scenes resembling nothing as much as the carefully choreographed dancing of a display case of brightly-iced cupcakes. But that same sugar-sweet fanciness is entirely beguiling at the level of glossy fable; and this is, after all, Cinderella.

Beyond the look of the thing, the film enjoys a pretty terrific cast; with a blank role to play, Craven can't do much, but it's not her film. This movie belongs entirely to the grown-ups: the icy but still human Lockwood, the sputtering, lovable Hordern, the calm and stern Bowers, and chiefly and above all Evans, who plays the most generic role imaginable - the old lady has no idea what's going on, har har - but does so with the most infectious possible brio. It's caricature at it's absolute best, and Evans's performance is the most effortless kind of scene-stealing.

Really, the performances and style are so good that even with the leaden final hour, The Slipper and the Rose could still sparkle; the only thing holding it down to the level of generally charming trifle that's far more boring than it has any cause to be is, I hate to say, the songs by the Sherman brothers. So many delectable scores for Disney came out of those two minds! And yet the 12 songs here are pretty much just one banality after another: perfectly serviceable tunes matched to lyrics that are infinitely clever and proud of their twisty wordplay, without being actually funny; the love ballads are at least a touch more concrete than the prattle-heavy comic numbers, but they're also a bit treacly. Either way, the songs come off as a bit strained and brittle, and they're derivative in obvious ways from the Shermans' earlier, better-known, and just plain stronger songs: it doesn't help that the odd "well, let's go ahead and talk about the class struggle" tune "Position and Positioning" steals its choreography straight from "Step In Time" from Mary Poppins, in case anybody had made it that far into the film without flashing back to the Shermans' most iconic musical.

Snip out the songs, though, and The Slipper and the Rose is a cutely off-kilter riff on a familiar story, with just enough peculiar fascination with the unexplored ramifications of that story to feel like its own thing. Obviously, "snip out the songs" is about as bad a thing as anybody could say about a feature-length musical; but the vivid craftsmanship and thoroughly delightful character acting is enough to make a surprisingly enjoyable experience out of the film, even as it fails what theoretically ought to be its most basic test.

Categories: british cinema, costume dramas, fantasy, love stories, musicals