You never open your mouth until you know what the shot is

A review requested by Andrew Yankes, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

Here's something of a paradox: David Mamet doesn't know shit about directing films, if we're to judge from his 1991 book On Directing Films (as pristine an example I can name of the bizarre fixation that many theater professionals apparently have on cinema as good for only the most ascetic kind of realism), and yet he is absolutely the best director of David Mamet films that has ever been. This is possibly because the viciously lean aesthetic he preaches and practices is so uniquely well-suited to showing off the tightly machined, rhythmic dialogue upon which his entire career has been based. At any rate, nobody does Mamet like Mamet, and the other attempts to do so have been all over the map, quality-wise.

But we have the good fortune to now train our attention on maybe the best of all Mamet movies directed by somebody else, the 1992 adaptation of his 1984 Pulitzer-winning play Glengarry Glen Ross, as directed by James Foley.* In latter days, Foley has found his niche as a prolific director of episodes of House of Cards, and this speaks directly to his primary qualification for adapting an enormously popular play: he is a great facilitator who doesn't try to get in the way of material with his own personalising stamp. In the case of Glengarry, this means (on the good side of the ledger) that maximum attention is drawn to the words being spoken and the actors speaking them, and quite a spectacular marriage that proves to be; it also means (on the bad side) that the film is a bit stilted as a film: there some visual ideas that play and some that don't, but mostly there aren't really ideas at all, just a choppy series of close-ups where we might prefer a longer wide shot to allow the actors to throw lines and pacing back and forth, rather than have editor Howard Smith do all the work for them.

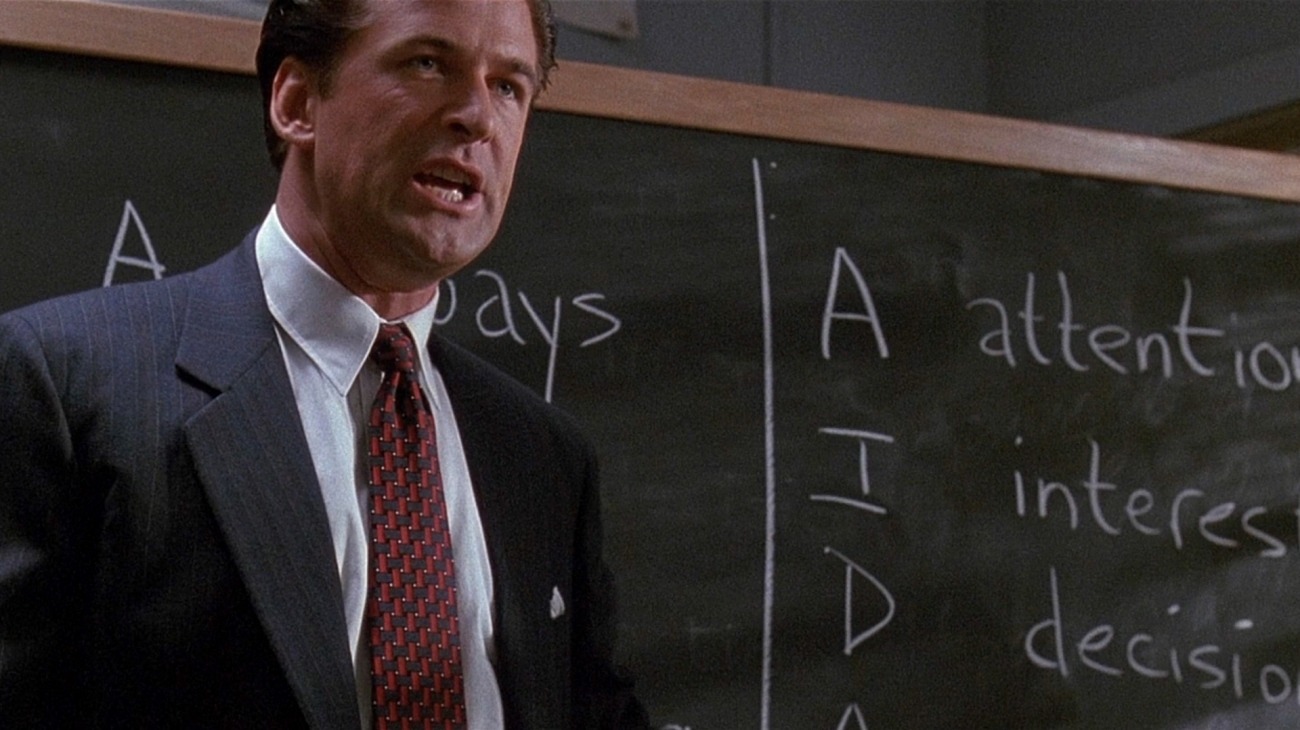

As an expression of a great fucking script, though, Glengarry really can't be beat. The piece itself is a modern classic: Mamet's revisiting of the themes of Death of a Salesman with the added disillusionment of the 1980s and enough profanity to choke a motherfucker. In a crappy little dive office in The Big City (played by New York, but not inherently required to be there), four men sweat and hustle and try to bilk middle class marks out of their retirement money with shady real estate deals: Ricky Roma (Al Pacino) is the current star of the office, though it takes very little effort to outsell George Aaronow (Alan Arkin), Dave Moss (Ed Harris), and especially Shelley Levene (Jack Lemmon), an old-timer who lost his game and blusters around in a haze of tart-tongued flop sweat. We meet them on a dank, rainy night when a fire has been lit under their collective asses: Mitch and Murray, the owners of the office, have called in a motivational speaker (Alec Baldwin) - "Blake", he's called in the credits, but I don't believe he gets named onscreen - who has come with a sales contest: first place is a Cadillac El Dorado, second prize is a set of steak knives, third prize is you're fired. And with slimy little office manager John Williamson (Kevin Spacey) holding a precious set of promising sales leads away from everybody, the mood in the office is grim as a funeral while the salesmen try to scrape some money out of people with nothing better to do than listen to oily flim-flam on the phone.

Mamet re-wrote the play himself, adding the scene with Baldwin's character, and shifting around some scenes in the first half, and in the process made Glengarry Glen Ross, the screenplay, an even stronger piece of drama than the awfully good original. Much of that resides in the Baldwin scene, a fire-and-brimstone sermon from the depths of capitalism at its most merciless. "My name is fuck you" he snarls at one point, and it's a good laugh-line, well-delivered (in a cast that's strong across the board, it's no controversial opinion to propose that Baldwin is the clear stand-out). But it's also kind of true. This is indeed Fuck You, the embodied spirit of the American Dream at its most aggressive and savage, a tyrannical belief that winning is the only thing, and if you can only win by ripping your morality and humanity out at the roots in order to more effectively rape your way across the countryside, than all that says is that morality and humanity weren't things you needed in the first place. It's a caustic tirade that flawlessly sets the scene for all to follow: a bile-soaked depiction of white American men so deep in the toxic atmosphere of brutal economic competition that decades of post-War affluence have built up as the shining ideal of white American masculinity that they can't imagine anything outside of it.

The story has no heroes: when the pathetic achieve a measure of success, they only become the exact same profane bullies they had previously bemoaned, and when the pathetic continue to fail, they simply retrench into an ever more self-effacing space of servile diminishment. It's a scorched-earth approach to satire, but it works perfectly: if there is a less apologetic and more thorough dismantling of the basic precepts of American capitalism - work hard and you'll be rewarded, making the most money makes you the best person, success is manly and admirable - to have been filmed in the last 25 years, I cannot name it. And it's all enacted by the best cast you could imagine. As the most dynamic character and the one who most fully lives out the whole range of themes explored in the writing, Lemmon gave his best performance in the 32 years since The Apartment, which inevitably echoes here: one generation of the American Dream gone sour informing another in the body of a pleasant-looking old man with an ingratiating voice who lashes out like a wounded animal in humiliated anger that's visceral and unpleasant to watch. And even with all that, he's not clearly "better" than anybody else: the clenched guts and bitter line deliveries and sweaty tension delivered by Harris and Arkin, the calm masking a deep well of rage that marks one of Pacino's last great performances, and the clammy, unimpressed, small meanness of a pre-fame Spacey are all absolutely terrific, breathing life into Mamet's blackhearted fable and flawlessly dancing with his words.

And for enabling all of this, it's absolutely impossible to find fault with this Glengarry, which above all else does nothing wrong. In the first hour, in particular, it even does a lot right, in capturing the bright, gaudy lighting of the Chinese restaurant where the men do most of their hustling - a neon symbol of excessive, kitschy Americana that's omnipresent without being labored - and the claustrophobia of a horrid, wet night, the kind that's chilly outside and humid inside. But the film's sense of place is undone by Foley's highly segmented way of assembling it; this is a film that favors the individual line and close-up shot at the expense of the flow of the whole. It doesn't feel conventionally stagebound in the least: it's almost not stagebound enough, in fact, since the biggest liaibility the film has is failing to include multiple characters in the same frame at the same time. None of this comes even close to making Glengarry Glen Ross a poor experience: the material is brilliant and the actors will never be bettered. And it even passes my private "would this be every bit as good as a radio play?" test - the use of color and lighting are generally strong, and the sense of damp in the first half pervasive. It's not a masterpiece of cinema, though - a masterpiece of drama presented in a cinematic matrix, but not a masterpiece of cinema. And that is, however slightly, a disappointment.

*I leave as an asterisk to this topic Louis Malle's 1994 Vanya on 42nd Street, with a screenplay by Andre Gregory adapted from Mamet's translation of Anton Chekov.

Here's something of a paradox: David Mamet doesn't know shit about directing films, if we're to judge from his 1991 book On Directing Films (as pristine an example I can name of the bizarre fixation that many theater professionals apparently have on cinema as good for only the most ascetic kind of realism), and yet he is absolutely the best director of David Mamet films that has ever been. This is possibly because the viciously lean aesthetic he preaches and practices is so uniquely well-suited to showing off the tightly machined, rhythmic dialogue upon which his entire career has been based. At any rate, nobody does Mamet like Mamet, and the other attempts to do so have been all over the map, quality-wise.

But we have the good fortune to now train our attention on maybe the best of all Mamet movies directed by somebody else, the 1992 adaptation of his 1984 Pulitzer-winning play Glengarry Glen Ross, as directed by James Foley.* In latter days, Foley has found his niche as a prolific director of episodes of House of Cards, and this speaks directly to his primary qualification for adapting an enormously popular play: he is a great facilitator who doesn't try to get in the way of material with his own personalising stamp. In the case of Glengarry, this means (on the good side of the ledger) that maximum attention is drawn to the words being spoken and the actors speaking them, and quite a spectacular marriage that proves to be; it also means (on the bad side) that the film is a bit stilted as a film: there some visual ideas that play and some that don't, but mostly there aren't really ideas at all, just a choppy series of close-ups where we might prefer a longer wide shot to allow the actors to throw lines and pacing back and forth, rather than have editor Howard Smith do all the work for them.

As an expression of a great fucking script, though, Glengarry really can't be beat. The piece itself is a modern classic: Mamet's revisiting of the themes of Death of a Salesman with the added disillusionment of the 1980s and enough profanity to choke a motherfucker. In a crappy little dive office in The Big City (played by New York, but not inherently required to be there), four men sweat and hustle and try to bilk middle class marks out of their retirement money with shady real estate deals: Ricky Roma (Al Pacino) is the current star of the office, though it takes very little effort to outsell George Aaronow (Alan Arkin), Dave Moss (Ed Harris), and especially Shelley Levene (Jack Lemmon), an old-timer who lost his game and blusters around in a haze of tart-tongued flop sweat. We meet them on a dank, rainy night when a fire has been lit under their collective asses: Mitch and Murray, the owners of the office, have called in a motivational speaker (Alec Baldwin) - "Blake", he's called in the credits, but I don't believe he gets named onscreen - who has come with a sales contest: first place is a Cadillac El Dorado, second prize is a set of steak knives, third prize is you're fired. And with slimy little office manager John Williamson (Kevin Spacey) holding a precious set of promising sales leads away from everybody, the mood in the office is grim as a funeral while the salesmen try to scrape some money out of people with nothing better to do than listen to oily flim-flam on the phone.

Mamet re-wrote the play himself, adding the scene with Baldwin's character, and shifting around some scenes in the first half, and in the process made Glengarry Glen Ross, the screenplay, an even stronger piece of drama than the awfully good original. Much of that resides in the Baldwin scene, a fire-and-brimstone sermon from the depths of capitalism at its most merciless. "My name is fuck you" he snarls at one point, and it's a good laugh-line, well-delivered (in a cast that's strong across the board, it's no controversial opinion to propose that Baldwin is the clear stand-out). But it's also kind of true. This is indeed Fuck You, the embodied spirit of the American Dream at its most aggressive and savage, a tyrannical belief that winning is the only thing, and if you can only win by ripping your morality and humanity out at the roots in order to more effectively rape your way across the countryside, than all that says is that morality and humanity weren't things you needed in the first place. It's a caustic tirade that flawlessly sets the scene for all to follow: a bile-soaked depiction of white American men so deep in the toxic atmosphere of brutal economic competition that decades of post-War affluence have built up as the shining ideal of white American masculinity that they can't imagine anything outside of it.

The story has no heroes: when the pathetic achieve a measure of success, they only become the exact same profane bullies they had previously bemoaned, and when the pathetic continue to fail, they simply retrench into an ever more self-effacing space of servile diminishment. It's a scorched-earth approach to satire, but it works perfectly: if there is a less apologetic and more thorough dismantling of the basic precepts of American capitalism - work hard and you'll be rewarded, making the most money makes you the best person, success is manly and admirable - to have been filmed in the last 25 years, I cannot name it. And it's all enacted by the best cast you could imagine. As the most dynamic character and the one who most fully lives out the whole range of themes explored in the writing, Lemmon gave his best performance in the 32 years since The Apartment, which inevitably echoes here: one generation of the American Dream gone sour informing another in the body of a pleasant-looking old man with an ingratiating voice who lashes out like a wounded animal in humiliated anger that's visceral and unpleasant to watch. And even with all that, he's not clearly "better" than anybody else: the clenched guts and bitter line deliveries and sweaty tension delivered by Harris and Arkin, the calm masking a deep well of rage that marks one of Pacino's last great performances, and the clammy, unimpressed, small meanness of a pre-fame Spacey are all absolutely terrific, breathing life into Mamet's blackhearted fable and flawlessly dancing with his words.

And for enabling all of this, it's absolutely impossible to find fault with this Glengarry, which above all else does nothing wrong. In the first hour, in particular, it even does a lot right, in capturing the bright, gaudy lighting of the Chinese restaurant where the men do most of their hustling - a neon symbol of excessive, kitschy Americana that's omnipresent without being labored - and the claustrophobia of a horrid, wet night, the kind that's chilly outside and humid inside. But the film's sense of place is undone by Foley's highly segmented way of assembling it; this is a film that favors the individual line and close-up shot at the expense of the flow of the whole. It doesn't feel conventionally stagebound in the least: it's almost not stagebound enough, in fact, since the biggest liaibility the film has is failing to include multiple characters in the same frame at the same time. None of this comes even close to making Glengarry Glen Ross a poor experience: the material is brilliant and the actors will never be bettered. And it even passes my private "would this be every bit as good as a radio play?" test - the use of color and lighting are generally strong, and the sense of damp in the first half pervasive. It's not a masterpiece of cinema, though - a masterpiece of drama presented in a cinematic matrix, but not a masterpiece of cinema. And that is, however slightly, a disappointment.

*I leave as an asterisk to this topic Louis Malle's 1994 Vanya on 42nd Street, with a screenplay by Andre Gregory adapted from Mamet's translation of Anton Chekov.