Misapplied science

A review requested by Sara L, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

Anthology films are always a shaky prospect, but they don't come more clear-cut and solid in conception than Memories, a 1995 animated film in three parts. It is nothing more complex than an adaptation of three short stories from manga artist Otomo Katushiro, unquestionably known best in the English-speaking world as the author and director of 1988's Akira, the film with which anime broke out in the West. He was on board to oversee Memories as executive producer and director of the last of its segments, but otherwise there's no obvious attempt to unify the three stories, each of which offer a different tone and completely different style. They are linked only by the theme that it's easy for humans to over-use technology without thinking about what we're doing; but that would likely have been the theme of any Otomo-derived anthology.

The result of filtering one man's thoughts through three different filmmaking sensibilities paid off well: unlike a great many anthology films, Memories doesn't have a weak link, though it feels that way while you're watching it, kind of. For it's terrifically imbalanced: the segment that is, far and away, the most stylistically inventive is also, far and away, the most shoddily constructed as a narrative, and the film commits the gaping structural error of leading off with its best segment by such a totally unfair margin that it tends to make the other segments feel a great deal more disappointing in comparison than they deserve.

It's also, quite incidentally, the only one of the three to meaningfully earn the title Memories; and not incidentally, the one that feels least of a piece with the attitude of the other two. Which I wish to believe, largely out of auteur loyalty and not for any real reason, is because it was written by Kon Satoshi, not yet a major director in his own right (his debut feature, Perfect Blue, was two years in the future) - the director in this case was Morimoto Koji, an animator of some note (he served as animation director on of the marvelous 2004 Mind Game), but who hadn't prior to this film had much chance to show off his directorial talents.

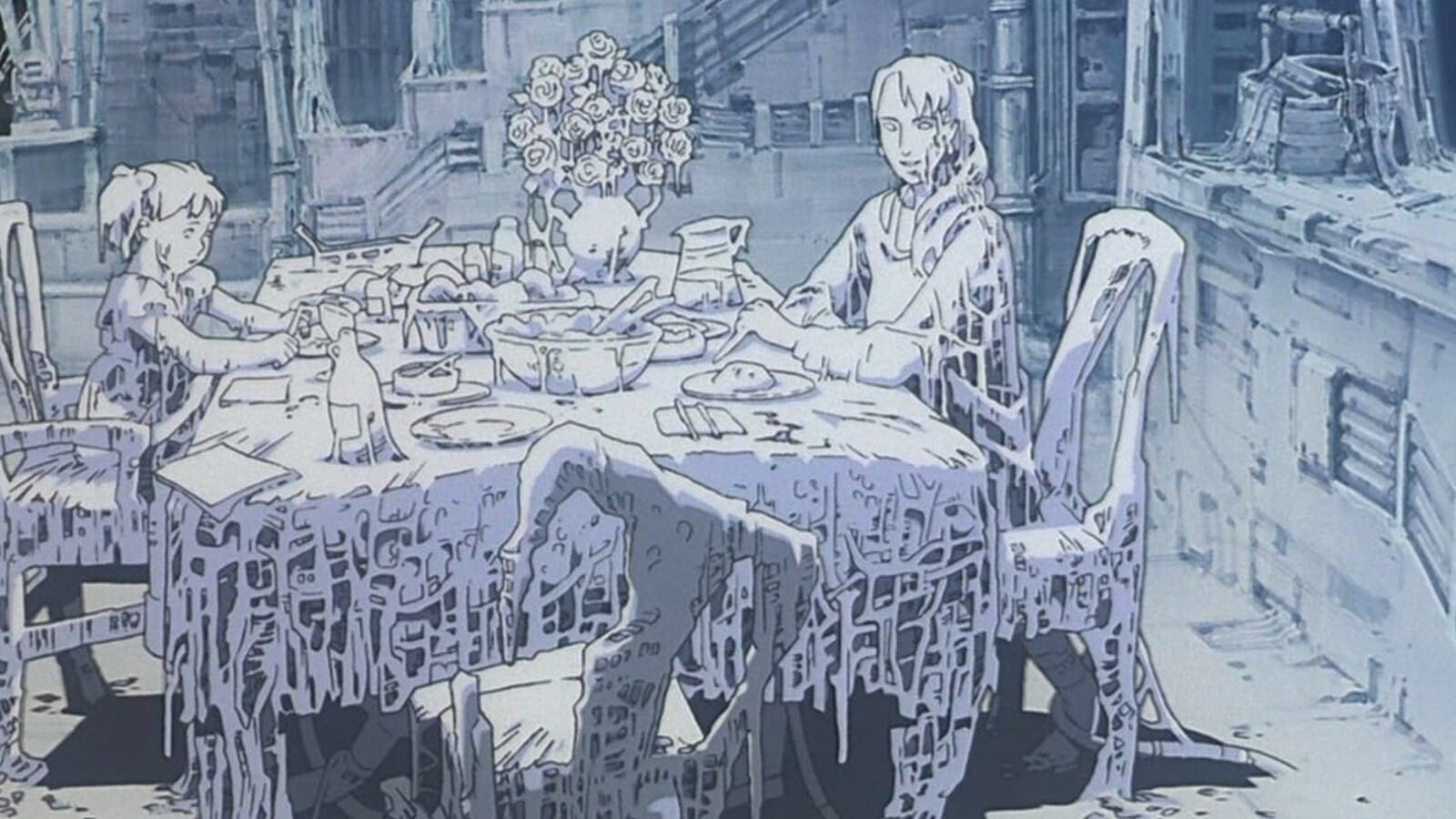

This opening movement, "Magnetic Rose", is the most conventional science-fiction piece in the film, taking place in deep space, where the crew of a salvage ship responds to a distress call from what appears to be a derelict station. That whole song and dance. The crewmembers who head onto the station to investigate that we need to be most concerned with are Heinz (Isobe Tsutomu) and Miguel (Yamadera Koichi), and what they find beggars belief: the inside of the station exactly resembles a plush European mansion of centuries earlier, right down to a simulation of the gardens outside. And it's haunted, apparently, by the presence of Eva (Takashima Gara), an opera singer with a tragic life that led directly to the psychologically fracturing mysteries of the place: Miguel begins to lose his grasp on reality and his own identity, while Heinz is tormented by visions of his dead daughter and promised that he can reside in his memories of his family forever.

There's nothing here that reinvents the wheel, either as a sci-fi fable or a work of animation, but as a mood piece about people being consumed by their pasts, it's hard to imagine "Magnetic Rose" being any better. The sagging, ancient sense of rotted opulence in the backgrounds is staggering, and perfectly matched to Maria Callas's performance of the iconic aria "Un bel dì vedremo" from Madama Butterfly, a song that sounds beautifully mournful in all the right ways, and which itself expresses similar themes of obsession with the lost past as the sequence containing it. "Magnetic Rose" is explicitly about the way that too much time stuck in memory can make it impossible to distinguish between what is true and right and what's merely illusion; the sci-fi trappings literalise that in the form of robots and holograms, but the emotional resonance of the piece is contained more in its faded old world settings and the heaving operatic music. It's old fashioned with crackling generic elements, tremendously accessible and deeply resonant, and it sets the bar for the rest of the film extravagantly high.

And, well, the rest of the film smacks into that bar. The second segment, "Stink Bomb", written by Otomo and directed by Okamura Tensai (who, unlike his co-directors, has worked almost exclusively in television, outside of this film, coming early in his career), is a strong black comedy in its own right, but frankly a bit goofy and one-note compared to "Magnetic Rose". It centers on Nobuo (Hori Hideyuki), a somewhat dim lab technician at a medical research firm, who get pushed into trying some experimental pills for fever when he comes to work sick. Except that he takes the wrong pills, and ingests a bio-warfare concoction instead, and once it enters its system, it reacts terribly with his body, causing him to emit a noxious, toxic gas that kills all animal life and triggers massive plant growth. The clouds of stench emanating from his body pervade the city so effectively that it becomes a national crisis almost immediately, and then an international one, as the U.S. military intercedes to capture Nobuo for their own ends.

The satire is blunt but not thus ineffective; casting secret weapons research as a badly safeguarded game played by blustering politicians and easily fucked up by a workaday dope is rather more biting and cynical and effective than putting it in the realm of shadowy melodrama. The bigger problem "Stink Bomb" has is that it's full of missed potential to be something even more interesting - the story's best and most haunting moments, of which there are several, all hinge on the sense of confusion, loneliness, and terror Nobuo feels at being plunged into a world where everything around him is dying, and heavily suited soldiers are hellbent on capturing him for reasons he doesn't understand. There's a sense of desolation that feels like something out of George A. Romero, the genre film as metaphor for social loss and isolation; crisply captured in the visuals and wonderfully acted out in the rich, heavily expressive animation of Nobuo's singularly well-designed face, it's quite a beautiful and touching thing, when it happens. And then it shifts back to the sardonic, bleak satire, and it feels like something goes out of it when that happens, a little bit every time.

It also starts to get wearisome before the segment's 40 minutes are up (it's just a bit shorter than "Magnetic Rose", and quite a bit longer than the finale) that Nobuo is such an utter dimwit. All of the strongest moments would be even stronger with a more knowing, self-aware person of largely average intelligence in the center; the plot mechanics work the same either way. By putting such a comic schlub in the central role, "Stink Bomb" scores some laughs, but at the expense of depth.

The last segment, Otomo's "Cannon Fodder", goes even deeper into overt satiric commentary than "Stink Bomb", while almost totally eschewing story. It's set in a nameless city state whose entire culture seems to be based around its series of building-sized cannons, fired multiple times every day at the neighboring enemy city, never seen by any of the cannon city's residents. Our tour guide for this militaristic world is a boy (Hayashi Isamu) whose father (Yamada Keaton) is a loader on Cannon 17, a necessary job but one that lacks the glamor or prestige of the cannon-firer, and is accompanied by no end of shitty working conditions.

Nothing "happens" - it's just a single day slice of life - but Otomo stuffs a great deal into the twenty-some minutes of his segment, managing to present a complete portrait of a 1984-style society in a constant state of war against an enemy that very possibly doesn't exist, and has been in even the smallest details of dress and decoration built around the idea of admiring its military, while also throwing out ideas about the oppression and exploitation of the working class that get far less screen time but still feel quite well fleshed-out. It's idea driven, and those ideas are important and urgently presented, though there's an inevitable dryness that comes from having only concepts, no drama.

Instead, all the dynamism in "Cannon Fodder" comes from its aesthetic, which is absolutely magnificent: the first two segments both use relatively straightforward anime style, but this one starts off with rough lines and smudgy coloring that feels exactly like pencil sketches, only done using cels. It's beautiful and striking, and that's only the least unique aspect of the style. The character design is even more idiosyncratic, primitive and almost inhuman in its presentation of the toothy humanoids with their lumpy builds and necrotic colors, all the better to stress the bedraggled, sickly lives of the workers, and the puffy inauthenticity of the military-approved heroes. But the most impressive thing of all, beyond doubt, is the gonzo ambition of the "camera movement", using what I suppose has to be CGI in concert with elaborate, difficult drawings to flow images together in a steady stream of sinuous shots in and around the film's world and all its trappings. It's involving and hypnotic, beautifully executed and astonishingly daunting in conception, and it's excellently suited to drawing us into the setting that is the primary reason "Cannon Fodder" exists at all.

Sure, it's a bit academic and detached, but it's smart as hell. That's true of everything in Memories: it is a most thoughtful collection of sci-fi notions, lovely to look at and troubling to contemplate. Like any anthology, it can't help but feel misshapen, but even its weakest moments are still awfully successful and worthwhile, and if the overall effect feels a bit less than the sum of its parts, that doesn't take away from how outstanding those parts are individually.

Anthology films are always a shaky prospect, but they don't come more clear-cut and solid in conception than Memories, a 1995 animated film in three parts. It is nothing more complex than an adaptation of three short stories from manga artist Otomo Katushiro, unquestionably known best in the English-speaking world as the author and director of 1988's Akira, the film with which anime broke out in the West. He was on board to oversee Memories as executive producer and director of the last of its segments, but otherwise there's no obvious attempt to unify the three stories, each of which offer a different tone and completely different style. They are linked only by the theme that it's easy for humans to over-use technology without thinking about what we're doing; but that would likely have been the theme of any Otomo-derived anthology.

The result of filtering one man's thoughts through three different filmmaking sensibilities paid off well: unlike a great many anthology films, Memories doesn't have a weak link, though it feels that way while you're watching it, kind of. For it's terrifically imbalanced: the segment that is, far and away, the most stylistically inventive is also, far and away, the most shoddily constructed as a narrative, and the film commits the gaping structural error of leading off with its best segment by such a totally unfair margin that it tends to make the other segments feel a great deal more disappointing in comparison than they deserve.

It's also, quite incidentally, the only one of the three to meaningfully earn the title Memories; and not incidentally, the one that feels least of a piece with the attitude of the other two. Which I wish to believe, largely out of auteur loyalty and not for any real reason, is because it was written by Kon Satoshi, not yet a major director in his own right (his debut feature, Perfect Blue, was two years in the future) - the director in this case was Morimoto Koji, an animator of some note (he served as animation director on of the marvelous 2004 Mind Game), but who hadn't prior to this film had much chance to show off his directorial talents.

This opening movement, "Magnetic Rose", is the most conventional science-fiction piece in the film, taking place in deep space, where the crew of a salvage ship responds to a distress call from what appears to be a derelict station. That whole song and dance. The crewmembers who head onto the station to investigate that we need to be most concerned with are Heinz (Isobe Tsutomu) and Miguel (Yamadera Koichi), and what they find beggars belief: the inside of the station exactly resembles a plush European mansion of centuries earlier, right down to a simulation of the gardens outside. And it's haunted, apparently, by the presence of Eva (Takashima Gara), an opera singer with a tragic life that led directly to the psychologically fracturing mysteries of the place: Miguel begins to lose his grasp on reality and his own identity, while Heinz is tormented by visions of his dead daughter and promised that he can reside in his memories of his family forever.

There's nothing here that reinvents the wheel, either as a sci-fi fable or a work of animation, but as a mood piece about people being consumed by their pasts, it's hard to imagine "Magnetic Rose" being any better. The sagging, ancient sense of rotted opulence in the backgrounds is staggering, and perfectly matched to Maria Callas's performance of the iconic aria "Un bel dì vedremo" from Madama Butterfly, a song that sounds beautifully mournful in all the right ways, and which itself expresses similar themes of obsession with the lost past as the sequence containing it. "Magnetic Rose" is explicitly about the way that too much time stuck in memory can make it impossible to distinguish between what is true and right and what's merely illusion; the sci-fi trappings literalise that in the form of robots and holograms, but the emotional resonance of the piece is contained more in its faded old world settings and the heaving operatic music. It's old fashioned with crackling generic elements, tremendously accessible and deeply resonant, and it sets the bar for the rest of the film extravagantly high.

And, well, the rest of the film smacks into that bar. The second segment, "Stink Bomb", written by Otomo and directed by Okamura Tensai (who, unlike his co-directors, has worked almost exclusively in television, outside of this film, coming early in his career), is a strong black comedy in its own right, but frankly a bit goofy and one-note compared to "Magnetic Rose". It centers on Nobuo (Hori Hideyuki), a somewhat dim lab technician at a medical research firm, who get pushed into trying some experimental pills for fever when he comes to work sick. Except that he takes the wrong pills, and ingests a bio-warfare concoction instead, and once it enters its system, it reacts terribly with his body, causing him to emit a noxious, toxic gas that kills all animal life and triggers massive plant growth. The clouds of stench emanating from his body pervade the city so effectively that it becomes a national crisis almost immediately, and then an international one, as the U.S. military intercedes to capture Nobuo for their own ends.

The satire is blunt but not thus ineffective; casting secret weapons research as a badly safeguarded game played by blustering politicians and easily fucked up by a workaday dope is rather more biting and cynical and effective than putting it in the realm of shadowy melodrama. The bigger problem "Stink Bomb" has is that it's full of missed potential to be something even more interesting - the story's best and most haunting moments, of which there are several, all hinge on the sense of confusion, loneliness, and terror Nobuo feels at being plunged into a world where everything around him is dying, and heavily suited soldiers are hellbent on capturing him for reasons he doesn't understand. There's a sense of desolation that feels like something out of George A. Romero, the genre film as metaphor for social loss and isolation; crisply captured in the visuals and wonderfully acted out in the rich, heavily expressive animation of Nobuo's singularly well-designed face, it's quite a beautiful and touching thing, when it happens. And then it shifts back to the sardonic, bleak satire, and it feels like something goes out of it when that happens, a little bit every time.

It also starts to get wearisome before the segment's 40 minutes are up (it's just a bit shorter than "Magnetic Rose", and quite a bit longer than the finale) that Nobuo is such an utter dimwit. All of the strongest moments would be even stronger with a more knowing, self-aware person of largely average intelligence in the center; the plot mechanics work the same either way. By putting such a comic schlub in the central role, "Stink Bomb" scores some laughs, but at the expense of depth.

The last segment, Otomo's "Cannon Fodder", goes even deeper into overt satiric commentary than "Stink Bomb", while almost totally eschewing story. It's set in a nameless city state whose entire culture seems to be based around its series of building-sized cannons, fired multiple times every day at the neighboring enemy city, never seen by any of the cannon city's residents. Our tour guide for this militaristic world is a boy (Hayashi Isamu) whose father (Yamada Keaton) is a loader on Cannon 17, a necessary job but one that lacks the glamor or prestige of the cannon-firer, and is accompanied by no end of shitty working conditions.

Nothing "happens" - it's just a single day slice of life - but Otomo stuffs a great deal into the twenty-some minutes of his segment, managing to present a complete portrait of a 1984-style society in a constant state of war against an enemy that very possibly doesn't exist, and has been in even the smallest details of dress and decoration built around the idea of admiring its military, while also throwing out ideas about the oppression and exploitation of the working class that get far less screen time but still feel quite well fleshed-out. It's idea driven, and those ideas are important and urgently presented, though there's an inevitable dryness that comes from having only concepts, no drama.

Instead, all the dynamism in "Cannon Fodder" comes from its aesthetic, which is absolutely magnificent: the first two segments both use relatively straightforward anime style, but this one starts off with rough lines and smudgy coloring that feels exactly like pencil sketches, only done using cels. It's beautiful and striking, and that's only the least unique aspect of the style. The character design is even more idiosyncratic, primitive and almost inhuman in its presentation of the toothy humanoids with their lumpy builds and necrotic colors, all the better to stress the bedraggled, sickly lives of the workers, and the puffy inauthenticity of the military-approved heroes. But the most impressive thing of all, beyond doubt, is the gonzo ambition of the "camera movement", using what I suppose has to be CGI in concert with elaborate, difficult drawings to flow images together in a steady stream of sinuous shots in and around the film's world and all its trappings. It's involving and hypnotic, beautifully executed and astonishingly daunting in conception, and it's excellently suited to drawing us into the setting that is the primary reason "Cannon Fodder" exists at all.

Sure, it's a bit academic and detached, but it's smart as hell. That's true of everything in Memories: it is a most thoughtful collection of sci-fi notions, lovely to look at and troubling to contemplate. Like any anthology, it can't help but feel misshapen, but even its weakest moments are still awfully successful and worthwhile, and if the overall effect feels a bit less than the sum of its parts, that doesn't take away from how outstanding those parts are individually.