Abuses of power

A second review requested by David Greenwood, with thanks for contributing twice to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

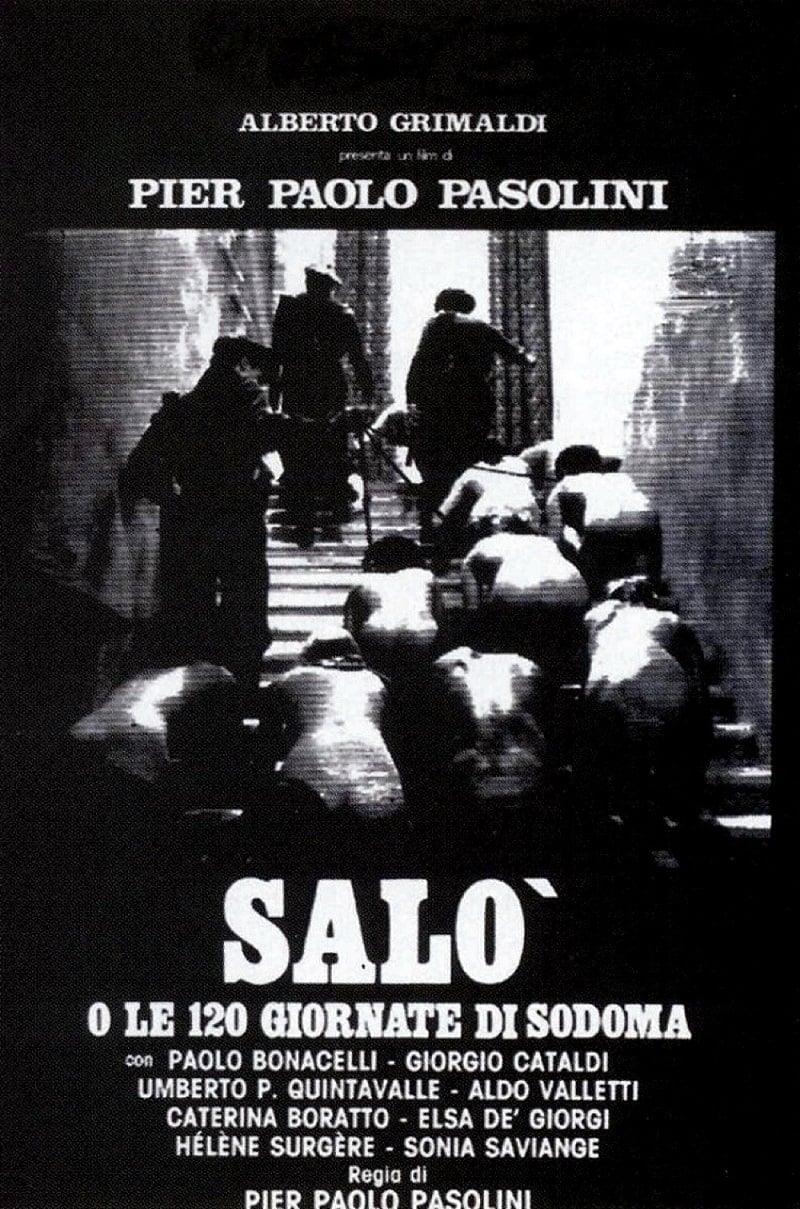

Knowing, as one can't help but know, that Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is the most god-damned notorious art film of them all for its grotesque displays of violence, warped sexuality, and bottomless imagination for depicting human cruelty, the film's opening is even more disorienting than it should be. And it's nothing but black titles on a white background! But underneath plays a jaunty, jazzy tune, Franco Ansaldo and Alfredo Bracchi's "Son tanto triste", promising a breezy tossed-off insincere experience to follow. In its own tiny way, it's as perverse and excruciating as anything that follows.

Truth be told, Salò's reputation for toxic, vile unwatchability is a bit overblown. It is, beyond question, a harrowing experience, and one that is very difficult to recommend - having at last seen it, I'm comfortable calling it an absolutely vital work of cinema that I'll never recommend to anybody for any reason - but it's nothing like a non-stop chamber of horrors that, once it stops, never lets up in punishing the audience. It's extremely formalised, in fact, and takes repeated stops to shift away from its depictions or even descriptions of depravity to indulge in circular conversation amongst its villains about European philosophy. True, these narrative pauses have a tendency to feel like the film is mustering its strength and drawing its breath for the next onslaught, so it's not like we're given a chance to relax in front of it. No, it keeps us pretty tense and wired throughout. Really, the parts of it that are most explicit are in some way the easiest to take, since at least in those cases we get to have a reaction and thus catharsis.

The film was the last to be directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose horrible murder came earlier in the same month as the film's November, 1975 premiere in France, giving its depiction of sexualised violence an extra charge of sickening potency - moreso when it was new than now, I am sure, and the papers aren't busily running photos of Pasolini's bloody corpse. He and Sergio Citti adapted it from the novel by the Marquis de Sade, added some of Dante's Inferno for the framework - though Salò describes only a one-way descent into Hell - and transposed the action to the Mussolini government during its final days as a puppet for the waning Nazi regime. How closely it hews to de Sade, I cannot begin to say, but taken on its own terms, the story adopts an almost poetic structure, built around four "stanzas", each moving through roughly the same sequence of events, while escalating the specific cruelty and intensity of those events. Simply put, the plot centers on a Duke (Paolo Bonacelli), a Bishop (Giorgio Cataldi), a Magistrate (Umberto P. Quintavalle), and the President (Aldo Valletti), who assemble a host of gorgeous young men and women, some kidnapped and some hired, to populate their castle on the outskirts of Salò, the capitol of the short-lived Italian Social Republic. There, they conduct an endless (or 120 days, anyway) experiment in causing humiliation and torture to their victims as a way of indulging their own pleasure. And that's basically it.

Pasolini's essays and interviews conducted in the last few years of his life leave virtually no ambiguity as to what he wanted to accomplish with this film, particularly in relationship to the three immediately preceding it in his career, the "Trilogy of Life" - The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, and Arabian Nights. Those films, the sunniest of his career, cumulatively present an idealised vision of pre-capitalist society, using primitive film technique and ancient storytelling style to depict sexual and social freedom, something not entirely unlike Rousseau's swoony Enlightenment-era adoration of noble savagery. In that way, it makes perfect sense that Pasolini would turn to de Sade, whose work was an explicit and purposeful contrast to Rousseau's optimism, showcasing the darker side of human possibility. For Pasolini, who had abandoned Marxism but not anti-capitalism at this point, the kind of joyful sexuality he had explored in the trilogy was fundamentally implausible in the corrupt capitalist world around him, based on relationship of power and the exploitation and ownership of the lower classes by the upper classes. It's not unusual to see Salò described as an anti-Fascist parable, using humiliation, torture, and rape as metaphors for the exploitation of a whole country by right-wing authoritarians during the war, but it's more the case that Fascism itself is also a metaphor, and the whole thing is a more general parable about the inherent abuses meted out by the self-indulgent leadership classes against the rest of society, baked into The System The Way It Is Now. This approach itself led to the film being attacked by the Italian intelligentsia, notably Italo Calvino, who viewed Pasolini's appropriation of Mussolini's real-life abuses to serve as an extreme parody in a provocative movie to be dangerously amoral.

That might very well be the case - the last thing I'm qualified to do is tell the intellectuals who lived through Fascism that they don't understand Fascism. Morally, I am genuinely uncertain what we should do with Salò, other than to firmly declare that it's grotesque excesses have very little in common with the like of torture porn or the Nazi sexploitation films of the same era. As cinema, though, the film is ingenious - one can debate the merits of Pasolini's intentions, but not the skill with which he carried them off, and even if we allow for Death of the Author and Intentional Fallacy and the like (and we should), there's no denying that the movie and themes the director described in the last year of his life is precisely the movie that we can watch today, those of us who don't live in countries where it's still illegal.

It's a marvelously crafty picture, Salò is, an enormous shift away from the artful crudeness of the Trilogy of Life and mostly unlike anything Pasolini ever did. It's a mercilessly aesthetic piece: the all-star team of production designer Dante Ferretti, set decorator Osvaldo Desideri, and costume designer Danilo Donati, in concert with Pasolini and cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli's proscenium-like framing along strict gridlines, gives Salò the polish, richness, and geometric precision of classical art; for a film so jam-packed with ugliness, it's gorgeous, like, constantly. But also chilly and mechanical: what none of the visuals do is give any life to the movie, and the customary hollowed-out sound design of Italian film production does nothing to combat that, nor do the dispassionate performances which (much like the sound), only really have much vibrancy to speak of during the cruelest acts depicted. The film is so sharp and precise that it feels totally artificial, and the whole time one watches it, one is first and always aware of the artifice on display: the fussy staging, the inorganic cutting, the way that depravity turns on and off like a light switch.

It becomes uncomfortably clear, in other words, that the film anticipates an audience - ourselves, and probably Pasolini too, whose sexual proclivities weren't entirely unlike some of the ones being depicted in the film as so ugly. Particularly viewed in the context of Tree of Life, Salò is obviously a scream of primal rage, directed at a world where everything is cruel and even something as beautiful as sex has been curdled and turned into a device for the powerful to assert their control over the powerless (I'm not sure that I've ever seen a movie that so bluntly insists on rape as a totally de-eroticised act). But it is not righteous. It indicts itself, its maker, and its viewers for existing in the same system of abuse and exploitation as its subjects; even as the victimised characters start to become increasingly complicit in sustaining the sordid world they're suffering through, it grows harder to deny that Salò isn't letting us off the hook. Isn't it a beautiful movie to just look at? Aren't the many young men and women seen naked throughout the film attractive? Yes and yes - that's the movie's trap for us, for even though it's as thoroughly unpleasant as any film that does not depict actual dead humans or animals could possibly be, Salò anticipates its status as an unspeakable provocation, one of those movies that we all go see precisely because they're so shocking and upsetting and horrible. The film tricks us, though: first by including so much material that's upsetting without being shocking, its long passage of depressingly violent stories and shitty jokes and its slow-paced development of the visual and narrative rules, and sitting listening to its characters talk about how utterly vile they are without punishing them for it. And then when the shocks start to come, they're staged in a way that makes us feel like voyeurs - explicitly so, in one of the final moments. It's a film that indicts everything, up to and including itself for existing in the world it depicts.

It's a one-of-a-kind mixture of rarefied intellectualism and disgusting visceral spectacle, and its themes are so severe as to feel like a howl of despair more than an articulate statement of radical politics. But it is pure cinema. I was not glad to see it while I was watching it, but I'm glad to have seen it; it is quite a thing to grapple with. Movies like this simply don't exist: that's arguably a good thing, but it certainly makes Salò stand out as a singular artistic accomplishment.

Knowing, as one can't help but know, that Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom is the most god-damned notorious art film of them all for its grotesque displays of violence, warped sexuality, and bottomless imagination for depicting human cruelty, the film's opening is even more disorienting than it should be. And it's nothing but black titles on a white background! But underneath plays a jaunty, jazzy tune, Franco Ansaldo and Alfredo Bracchi's "Son tanto triste", promising a breezy tossed-off insincere experience to follow. In its own tiny way, it's as perverse and excruciating as anything that follows.

Truth be told, Salò's reputation for toxic, vile unwatchability is a bit overblown. It is, beyond question, a harrowing experience, and one that is very difficult to recommend - having at last seen it, I'm comfortable calling it an absolutely vital work of cinema that I'll never recommend to anybody for any reason - but it's nothing like a non-stop chamber of horrors that, once it stops, never lets up in punishing the audience. It's extremely formalised, in fact, and takes repeated stops to shift away from its depictions or even descriptions of depravity to indulge in circular conversation amongst its villains about European philosophy. True, these narrative pauses have a tendency to feel like the film is mustering its strength and drawing its breath for the next onslaught, so it's not like we're given a chance to relax in front of it. No, it keeps us pretty tense and wired throughout. Really, the parts of it that are most explicit are in some way the easiest to take, since at least in those cases we get to have a reaction and thus catharsis.

The film was the last to be directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose horrible murder came earlier in the same month as the film's November, 1975 premiere in France, giving its depiction of sexualised violence an extra charge of sickening potency - moreso when it was new than now, I am sure, and the papers aren't busily running photos of Pasolini's bloody corpse. He and Sergio Citti adapted it from the novel by the Marquis de Sade, added some of Dante's Inferno for the framework - though Salò describes only a one-way descent into Hell - and transposed the action to the Mussolini government during its final days as a puppet for the waning Nazi regime. How closely it hews to de Sade, I cannot begin to say, but taken on its own terms, the story adopts an almost poetic structure, built around four "stanzas", each moving through roughly the same sequence of events, while escalating the specific cruelty and intensity of those events. Simply put, the plot centers on a Duke (Paolo Bonacelli), a Bishop (Giorgio Cataldi), a Magistrate (Umberto P. Quintavalle), and the President (Aldo Valletti), who assemble a host of gorgeous young men and women, some kidnapped and some hired, to populate their castle on the outskirts of Salò, the capitol of the short-lived Italian Social Republic. There, they conduct an endless (or 120 days, anyway) experiment in causing humiliation and torture to their victims as a way of indulging their own pleasure. And that's basically it.

Pasolini's essays and interviews conducted in the last few years of his life leave virtually no ambiguity as to what he wanted to accomplish with this film, particularly in relationship to the three immediately preceding it in his career, the "Trilogy of Life" - The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, and Arabian Nights. Those films, the sunniest of his career, cumulatively present an idealised vision of pre-capitalist society, using primitive film technique and ancient storytelling style to depict sexual and social freedom, something not entirely unlike Rousseau's swoony Enlightenment-era adoration of noble savagery. In that way, it makes perfect sense that Pasolini would turn to de Sade, whose work was an explicit and purposeful contrast to Rousseau's optimism, showcasing the darker side of human possibility. For Pasolini, who had abandoned Marxism but not anti-capitalism at this point, the kind of joyful sexuality he had explored in the trilogy was fundamentally implausible in the corrupt capitalist world around him, based on relationship of power and the exploitation and ownership of the lower classes by the upper classes. It's not unusual to see Salò described as an anti-Fascist parable, using humiliation, torture, and rape as metaphors for the exploitation of a whole country by right-wing authoritarians during the war, but it's more the case that Fascism itself is also a metaphor, and the whole thing is a more general parable about the inherent abuses meted out by the self-indulgent leadership classes against the rest of society, baked into The System The Way It Is Now. This approach itself led to the film being attacked by the Italian intelligentsia, notably Italo Calvino, who viewed Pasolini's appropriation of Mussolini's real-life abuses to serve as an extreme parody in a provocative movie to be dangerously amoral.

That might very well be the case - the last thing I'm qualified to do is tell the intellectuals who lived through Fascism that they don't understand Fascism. Morally, I am genuinely uncertain what we should do with Salò, other than to firmly declare that it's grotesque excesses have very little in common with the like of torture porn or the Nazi sexploitation films of the same era. As cinema, though, the film is ingenious - one can debate the merits of Pasolini's intentions, but not the skill with which he carried them off, and even if we allow for Death of the Author and Intentional Fallacy and the like (and we should), there's no denying that the movie and themes the director described in the last year of his life is precisely the movie that we can watch today, those of us who don't live in countries where it's still illegal.

It's a marvelously crafty picture, Salò is, an enormous shift away from the artful crudeness of the Trilogy of Life and mostly unlike anything Pasolini ever did. It's a mercilessly aesthetic piece: the all-star team of production designer Dante Ferretti, set decorator Osvaldo Desideri, and costume designer Danilo Donati, in concert with Pasolini and cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli's proscenium-like framing along strict gridlines, gives Salò the polish, richness, and geometric precision of classical art; for a film so jam-packed with ugliness, it's gorgeous, like, constantly. But also chilly and mechanical: what none of the visuals do is give any life to the movie, and the customary hollowed-out sound design of Italian film production does nothing to combat that, nor do the dispassionate performances which (much like the sound), only really have much vibrancy to speak of during the cruelest acts depicted. The film is so sharp and precise that it feels totally artificial, and the whole time one watches it, one is first and always aware of the artifice on display: the fussy staging, the inorganic cutting, the way that depravity turns on and off like a light switch.

It becomes uncomfortably clear, in other words, that the film anticipates an audience - ourselves, and probably Pasolini too, whose sexual proclivities weren't entirely unlike some of the ones being depicted in the film as so ugly. Particularly viewed in the context of Tree of Life, Salò is obviously a scream of primal rage, directed at a world where everything is cruel and even something as beautiful as sex has been curdled and turned into a device for the powerful to assert their control over the powerless (I'm not sure that I've ever seen a movie that so bluntly insists on rape as a totally de-eroticised act). But it is not righteous. It indicts itself, its maker, and its viewers for existing in the same system of abuse and exploitation as its subjects; even as the victimised characters start to become increasingly complicit in sustaining the sordid world they're suffering through, it grows harder to deny that Salò isn't letting us off the hook. Isn't it a beautiful movie to just look at? Aren't the many young men and women seen naked throughout the film attractive? Yes and yes - that's the movie's trap for us, for even though it's as thoroughly unpleasant as any film that does not depict actual dead humans or animals could possibly be, Salò anticipates its status as an unspeakable provocation, one of those movies that we all go see precisely because they're so shocking and upsetting and horrible. The film tricks us, though: first by including so much material that's upsetting without being shocking, its long passage of depressingly violent stories and shitty jokes and its slow-paced development of the visual and narrative rules, and sitting listening to its characters talk about how utterly vile they are without punishing them for it. And then when the shocks start to come, they're staged in a way that makes us feel like voyeurs - explicitly so, in one of the final moments. It's a film that indicts everything, up to and including itself for existing in the world it depicts.

It's a one-of-a-kind mixture of rarefied intellectualism and disgusting visceral spectacle, and its themes are so severe as to feel like a howl of despair more than an articulate statement of radical politics. But it is pure cinema. I was not glad to see it while I was watching it, but I'm glad to have seen it; it is quite a thing to grapple with. Movies like this simply don't exist: that's arguably a good thing, but it certainly makes Salò stand out as a singular artistic accomplishment.