Blockbuster History: Your A.I. wants to kill you

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the Walt Disney Company is about to make a ridiculous sum of money on a movie about an artificial intelligence that goes violent, using the best and brightest visual effects available, in Avengers: Age of Ultron. They've done this before, absent the "ridiculous sum of money" part.

The whole matter of Disney's desperate attempt to court a teenage audience in the wake of Star Wars resulted in some of the most batty movies in that studio's history, but even within that company, 1982's TRON is particularly weird. It's brazenly marketing-driven: the conceit was transparently to tap into the new vogue for science fiction and simultaneously the even newer vogue for these "video games" that were apparently a big deal. And if that's not hook enough, the film is also a self-conscious landmark in the history of visual effects: it was the first feature with extensive use of computer-generated scenery and objects, about 15 minutes' worth. It was as shameless a piece of bandwagon-hopping and spectacle-first filmmaking as you could hope for then or anytime in the intervening three decades and change, blindly commercial in every way. And yet it's so deranged in every aspect of its conception and execution that you'd never, for a minute, think that the people who made it had even the smallest commercial designs.

TRON is a baffling mixture of tech arcana with computer science so far off the charts that it's infinitely more fair to call this a fantasy than anything else, grafted onto a script that's at its best when it's ridden with clichés - at it's worst, you can't even make out what the story is meant to be. The opening 15 minutes, for example, throw a seemingly random collection of moments at us, first diving inside the circuits of an arcade cabinet to show the gameplay affecting the software inside as a real life-and-death struggle, and then zipping rather recklessly over to a hacker, Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges), using a computer program named CLU to dig into some unspecified files, which consists of a humanoid CLU - who looks just like Flynn - interacting with a three-dimensional environment representing the interior of a computer system. Or maybe it really is three-dimensional, only you have to be microscopically small to perceive it. By the time we even start to process what's going on, we've arrived at Ed Dillinger (David Warner), former software engineer and current head of ENCOM, speaking to a self-aware program he's developed called the Master Control Program (which talks with Warner's voice) about Flynn's intrusions into their network. And then we stumble into ENCOM engineers Alan Bradley (Bruce Boxleitner) and Lora Baines (Cindy Morgan), without having received any idea of what's going on or how things fit together. That's not an unfair strategy, of course: the idea, I'd imagine, was to pique our interest by making things just unclear enough that we wouldn't be able to contain our sense of curiosity.

But the effect is nothing remotely so elegant: the opening quarter-hour is a murky mess that at once explains things in far too exhaustive detail (using the good old "let's discuss this thing that we both know about already" trick) while leaving everything that's actually important for a single exposition dump delivered by Bridges at full speed with minimal artfulness. It's difficult to put into words the perplexing way that TRON mixes incredibly blunt explanations with maddeningly obtuse loose ends - the kind of film that establishes the villains are evil by letting them swap lines like "You're becoming brutal, and needlessly sadistic." / "Thank you.", but never actually clarifying out what the villains do, other than run a dystopian dictatorship for the hell of it. Director and co-writer Steve Lisberger, an independent animator who originated the idea when he hit upon the world and visual effects concepts, had the exact sort of career before and after TRON that equips one to do many things that aren't tell a story or communicate ideas clearly, and his film suffers mightily from those flaws. It's easy enough to say that a world in which computer programs of every sort are sapient humanoids in a physical space of buildings and canyons doesn't "make sense"; but even once you've bought in to that as a requirement of the film's plot, TRON's world is perplexingly inconsistent in some of the places where the plot depends on it the most. Particularly regarding how much the programs know about their Users, and vice versa. The film ends up as a rather off-kilter religious allegory, on top of all its other quirks (it even updates the idea of throwing the faithful into a gladiatorial arena, in more or less precisely those terms), and failing to clarify what relationship the characters have to their gods makes it immensely hard to take that part seriously.

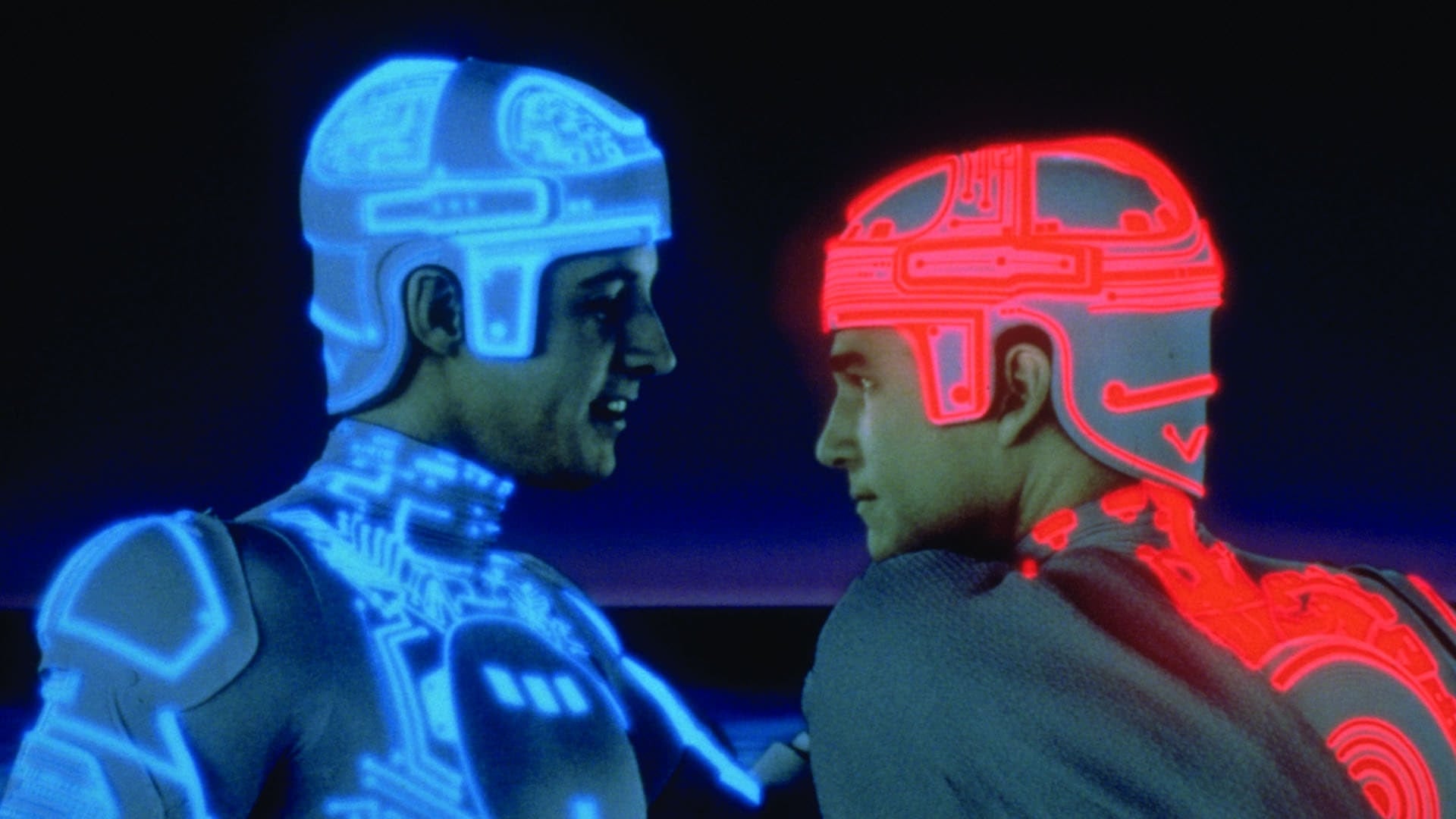

That's a lot of energy devoted to proving the thesis "TRON has a shitty script", which is about as uncontroversial a claim about this movie as I could possibly have made. That's not to say that the film is without its charms, though they're not as pronounced as in its 28-years-later sequel, TRON: Legacy, which is better at being a Daft Punk music video than TRON is at being anything. Still, while its visual effects have aged laughably poorly, the original movie can be quite lovely to look at, particularly since its CGI isn't trying to represent anything more realistic than 1982-era CGI. That is to say, it makes sense that the virtual world inside an early '80s computer would look rather monotone and blocky. It even seems right that the characters (shot in black and white with hand-colored details on their costumes) would feel so jerkily disconnected from their setting (animated backdrops, for the most part) - it adds to the synthetic feeling. If nothing else, TRON does a splendid job of presenting a disconcerting otherworld, one that poor Flynn never quite figures out - oh, right, Flynn ends up getting zapped by a laser while he's trying to hack the Master Control Program, where he meets up with Alan's anti-MCP security program TRON and they journey through a computer hellscape to get some kind of uplink with Alan. But mostly production and costume design happens, interspersed with visual effects, and given a disconcerting sonic texture by some really impressive sound work and a wonderfully unnatural electronic score by Wendy Carlos, as obvious a choice for this job in 1982 as Daft Punk was in 2010.

At a certain point, TRON's eerily smooth surfaces and harsh contrasts of primary colors simply end up working as purely abstract experience: colored shapes interacting with each other in a network of oddly soothing sounds, considering how grating they are. Given the inventive, strange workarounds the filmmakers had to go through to execute their ideas, workarounds that would almost immediately become unnecessary, no film has ever been obliged to look like this, so no film ever has (certainly not its own sequel). Most films that rely on their outdated visual effects tend to benefit from being seen through a certain haze, but not this: the bleedingly crisp delineations of lines and colors available in high definition end up leaving TRON look quite beautiful, for all its limited palette and omnipresent darkness. Don't think of it as a story, but an exercise in hue, geometry, and textures ranging from ethereal glossiness to intense grain, and it's downright pleasant.

That doesn't excuse how much of a life-sucking slog it is to get to the point that Flynn gets sucked into the computer. It is a deathly long first act, with nothing but Bridges's demented energy and Warner's ever-reliable voice to provide anything that even marginally distracts from how stupid and aimless everything that we're watching is. That's the problem with style-driven movies: you can't ease up on the style for even a second, and TRON spends so much time wallowing in the most utterly boring tripe that it's largely burned off any possible reservoir of audience goodwill even before it does anything to earn it.

The whole matter of Disney's desperate attempt to court a teenage audience in the wake of Star Wars resulted in some of the most batty movies in that studio's history, but even within that company, 1982's TRON is particularly weird. It's brazenly marketing-driven: the conceit was transparently to tap into the new vogue for science fiction and simultaneously the even newer vogue for these "video games" that were apparently a big deal. And if that's not hook enough, the film is also a self-conscious landmark in the history of visual effects: it was the first feature with extensive use of computer-generated scenery and objects, about 15 minutes' worth. It was as shameless a piece of bandwagon-hopping and spectacle-first filmmaking as you could hope for then or anytime in the intervening three decades and change, blindly commercial in every way. And yet it's so deranged in every aspect of its conception and execution that you'd never, for a minute, think that the people who made it had even the smallest commercial designs.

TRON is a baffling mixture of tech arcana with computer science so far off the charts that it's infinitely more fair to call this a fantasy than anything else, grafted onto a script that's at its best when it's ridden with clichés - at it's worst, you can't even make out what the story is meant to be. The opening 15 minutes, for example, throw a seemingly random collection of moments at us, first diving inside the circuits of an arcade cabinet to show the gameplay affecting the software inside as a real life-and-death struggle, and then zipping rather recklessly over to a hacker, Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges), using a computer program named CLU to dig into some unspecified files, which consists of a humanoid CLU - who looks just like Flynn - interacting with a three-dimensional environment representing the interior of a computer system. Or maybe it really is three-dimensional, only you have to be microscopically small to perceive it. By the time we even start to process what's going on, we've arrived at Ed Dillinger (David Warner), former software engineer and current head of ENCOM, speaking to a self-aware program he's developed called the Master Control Program (which talks with Warner's voice) about Flynn's intrusions into their network. And then we stumble into ENCOM engineers Alan Bradley (Bruce Boxleitner) and Lora Baines (Cindy Morgan), without having received any idea of what's going on or how things fit together. That's not an unfair strategy, of course: the idea, I'd imagine, was to pique our interest by making things just unclear enough that we wouldn't be able to contain our sense of curiosity.

But the effect is nothing remotely so elegant: the opening quarter-hour is a murky mess that at once explains things in far too exhaustive detail (using the good old "let's discuss this thing that we both know about already" trick) while leaving everything that's actually important for a single exposition dump delivered by Bridges at full speed with minimal artfulness. It's difficult to put into words the perplexing way that TRON mixes incredibly blunt explanations with maddeningly obtuse loose ends - the kind of film that establishes the villains are evil by letting them swap lines like "You're becoming brutal, and needlessly sadistic." / "Thank you.", but never actually clarifying out what the villains do, other than run a dystopian dictatorship for the hell of it. Director and co-writer Steve Lisberger, an independent animator who originated the idea when he hit upon the world and visual effects concepts, had the exact sort of career before and after TRON that equips one to do many things that aren't tell a story or communicate ideas clearly, and his film suffers mightily from those flaws. It's easy enough to say that a world in which computer programs of every sort are sapient humanoids in a physical space of buildings and canyons doesn't "make sense"; but even once you've bought in to that as a requirement of the film's plot, TRON's world is perplexingly inconsistent in some of the places where the plot depends on it the most. Particularly regarding how much the programs know about their Users, and vice versa. The film ends up as a rather off-kilter religious allegory, on top of all its other quirks (it even updates the idea of throwing the faithful into a gladiatorial arena, in more or less precisely those terms), and failing to clarify what relationship the characters have to their gods makes it immensely hard to take that part seriously.

That's a lot of energy devoted to proving the thesis "TRON has a shitty script", which is about as uncontroversial a claim about this movie as I could possibly have made. That's not to say that the film is without its charms, though they're not as pronounced as in its 28-years-later sequel, TRON: Legacy, which is better at being a Daft Punk music video than TRON is at being anything. Still, while its visual effects have aged laughably poorly, the original movie can be quite lovely to look at, particularly since its CGI isn't trying to represent anything more realistic than 1982-era CGI. That is to say, it makes sense that the virtual world inside an early '80s computer would look rather monotone and blocky. It even seems right that the characters (shot in black and white with hand-colored details on their costumes) would feel so jerkily disconnected from their setting (animated backdrops, for the most part) - it adds to the synthetic feeling. If nothing else, TRON does a splendid job of presenting a disconcerting otherworld, one that poor Flynn never quite figures out - oh, right, Flynn ends up getting zapped by a laser while he's trying to hack the Master Control Program, where he meets up with Alan's anti-MCP security program TRON and they journey through a computer hellscape to get some kind of uplink with Alan. But mostly production and costume design happens, interspersed with visual effects, and given a disconcerting sonic texture by some really impressive sound work and a wonderfully unnatural electronic score by Wendy Carlos, as obvious a choice for this job in 1982 as Daft Punk was in 2010.

At a certain point, TRON's eerily smooth surfaces and harsh contrasts of primary colors simply end up working as purely abstract experience: colored shapes interacting with each other in a network of oddly soothing sounds, considering how grating they are. Given the inventive, strange workarounds the filmmakers had to go through to execute their ideas, workarounds that would almost immediately become unnecessary, no film has ever been obliged to look like this, so no film ever has (certainly not its own sequel). Most films that rely on their outdated visual effects tend to benefit from being seen through a certain haze, but not this: the bleedingly crisp delineations of lines and colors available in high definition end up leaving TRON look quite beautiful, for all its limited palette and omnipresent darkness. Don't think of it as a story, but an exercise in hue, geometry, and textures ranging from ethereal glossiness to intense grain, and it's downright pleasant.

That doesn't excuse how much of a life-sucking slog it is to get to the point that Flynn gets sucked into the computer. It is a deathly long first act, with nothing but Bridges's demented energy and Warner's ever-reliable voice to provide anything that even marginally distracts from how stupid and aimless everything that we're watching is. That's the problem with style-driven movies: you can't ease up on the style for even a second, and TRON spends so much time wallowing in the most utterly boring tripe that it's largely burned off any possible reservoir of audience goodwill even before it does anything to earn it.