An unmarried woman

A review requested by John Smith, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

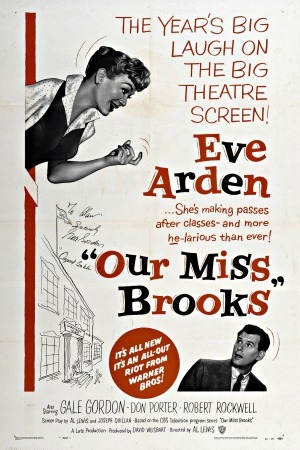

Against all reason and the evidence of the film itself, Our Miss Brooks is one of the most singular movies I've ever had occasion to talk about. As far as I can tell, it's the second feature film ever to be adapted from an episodic television series (Dragnet beat it by two years), perhaps the first theatrical movie to serve as an expanded series finale (it's not clear to me when exactly the film was released in 1956, the year that the fourth and final season of Our Miss Brooks aired on CBS), while simultaneously being the first theatrical remake of an episodic television series. If these last two points seem mutually exclusive, that's only because they are, and that's part of the strange fascination the Our Miss Brooks film holds.

And who is our Miss Brooks? She's a sharp-witted, put-upon English teacher at Madison High School, first portrayed by Eve Arden on a hugely successful radio show that started in 1949 and outlived both the TV and cinematic incarnations of the same character played by the same actor. As I understand it, the show balanced four years of her work dealing with the repugnant principal Osgood Conklin (Gale Gordon), teaching some kids who were comically dumb, pining for her boyfriend, hunky biology teacher Phil Boynton (Robert Rockwell), to finally just goddamn propose to her already, and kvetching to her gossipy landlady Mrs. Davis (Jane Morgan) about all of the above. The movie does much the same thing, though in a more ambitious and compressed frame; it opens with Connie Brooks's arrival in town, blurs through anything from several months to several years in a whirlwind, and then lands on most of its actual plotlines, circling around the tortured politicking by which Conklin convinces Connie to support his bid to be made district superintendent in exchange for his promise to make Phil the new principal at Madison, thus clearing the way for him to finally be able to afford to pop the question. Meanwhile, Connie is tutoring the bright but lazy and underperforming Gary Nolan (Nick Adams), son of newspaper magnate Lawrence Nolan (Don Porter), one of the richest men in town. And Lawrence is quite taken with Connie's sardonic spunkiness, and he's much less reluctant to show it than Phil has been after all this time dating.

Two thoughts: this leaves us with another possible explanation for the movie: it's a wraparound prequel and finale to the show, but one which is enabled to function as a complete standalone narrative because the prequel elements do a fine job setting up all the characters and situations (it is, in fact, maybe the only TV series adapted into a movie with the same cast by the same creators I've seen that doesn't feel like it's trading on the viewer's knowledge of the show whatsoever; and this despite being a big hit when there were only three networks). And in this it is not merely the first of its kind, but maybe also the only one.

The other thought: golly gee whiz, the '50s, huh? It's not the only decade in American cinema where the motivating force behind the plot would be the female lead conniving to get her boyfriend a higher paying position so he could afford to propose to her so she could quit a job she was good at and enjoyed. But it's probably the decade where it doesn't seem that there could have been any other option. It's easy to get hung up on that kind of thing, and not very edifying intellectually, but still, it makes for an extraordinarily weird viewing experience; so heavily invested in the most reactive kind of Eisenhower Era social conservatism that one starts to wonder if the thing to do is regard it as some manner of deliberate camp. It can't really be that, of course. It definitely triggers our emotional responses in straightforward ways that assume that yes, we can't think of a better task for an adult woman with talent as a schoolteacher than to be constantly on a man hunt.

It does everything pretty straightforwardly, for that matter. The creative leads, director and co-writer Al Lewis, and co-writer Joseph Quillan, were both primarily veterans of TV - of Our Miss Brooks itself, naturally - and while the statement "this theatrical motion picture looks and feels like an episode of television" no longer has quite the same bite in 21st Century, back in '56, there's pretty much no upshot to that criticism. Our Miss Brooks has a crew who came mostly out of the movies, including Oscared cinematographer Joseph LaShelle and producer David Weisbart, a year after he oversaw Rebel Without a Cause, and all combined, they're just about able to force a kind of cinematic visual scale onto the material that balances out, if not exactly compensates for, the grimly by-the-numbers screenwriting. This is not the kind of comedy that startles you and catches you off guard; it is the kind for which the set-up for future gags is done that an even slightly savvy viewer will be able to map out the exact timing of the jokes sometimes whole scenes in advance. It is possible that this is what a half-century of sitcom evolution does for us, and viewers in '56 would have been quite absorbed by the comic shenanigans before them. But that requires assuming that World War II made everybody so stupid that they'd forgotten about comedy in the '30s.

This is, then, sitcom humor: big, broad, obvious sitcom humor. Stating that feels less like an insult than a simple definition. The weird thing about the movie, though, is that it's doofy comedy doesn't seem to matter really. There's nothing bigger, or broader, or more obvious in the film than Arden's mugging - she pulls faces like the bronze medalist at a Harpo Marx competition, wheeling her head around to grimace and bug out every one of her features simultaneously, somehow, to let us know exactly how mortified Connie is by the obviousness and venality of all the people she interacts with on a daily basis. It's not "acting" quite as much as it is "pantomime". And yet, while being the most conspicuously unhinged thing to be found onscreen, Arden is also clearly the film's saving grace. Her cartoon exaggerations, entirely out of proportion to the mild japery that goes on, push the film into a weirdly subjective realm, in which we find ourselves plugging through the constant bombardment of petty indignities that our Miss Brooks has to suffer through right along with her.

It provides an inexplicable tether of emotional honesty to a tossed-off lark that registers as a comedy more because of its happy lack of substance than because anything within it is particularly funny - comedy being subjective and all, I still don't feel even a little bit guilty about how much I wasn't laughing nor being tempted to laugh throughout the movie. It's tremendously easy to like Connie Brooks, to find her opponents offensive and her lovers frustratingly obtuse, simply because Arden has such an easy way of falling into the character's clownish beats, and make them feel comfortable. That's the TV connection, I have no doubt: even without trading on the viewer's relationship with the show (which was entirely nonexistent, for this viewer), it trades on the performers' relationship with the show, and the acting shorthand and fully worked-out personality that the performers have built. Our Miss Brooks is rather plain-looking cinema, and rote storytelling, and I doubt I'll have concrete memories of it a year from now. And yet, in the moment of watching it, Arden and some of her costars (not, unfortunately, Rockwell, a terribly uninvolving romantic lead) present characters who've been sharply-etched to the point that it's easy to get invested in watching them even if what they're doing isn't particularly interesting. That's a bizarre half-triumph, but it's far more than I expected when I started the movie or even during its pokey opening ten minutes, and I find myself fondly disposed towards Our Miss Brooks despite the paucity of things I can point to and state, firmly, "oh, I liked that." Television is just weird that way.

Against all reason and the evidence of the film itself, Our Miss Brooks is one of the most singular movies I've ever had occasion to talk about. As far as I can tell, it's the second feature film ever to be adapted from an episodic television series (Dragnet beat it by two years), perhaps the first theatrical movie to serve as an expanded series finale (it's not clear to me when exactly the film was released in 1956, the year that the fourth and final season of Our Miss Brooks aired on CBS), while simultaneously being the first theatrical remake of an episodic television series. If these last two points seem mutually exclusive, that's only because they are, and that's part of the strange fascination the Our Miss Brooks film holds.

And who is our Miss Brooks? She's a sharp-witted, put-upon English teacher at Madison High School, first portrayed by Eve Arden on a hugely successful radio show that started in 1949 and outlived both the TV and cinematic incarnations of the same character played by the same actor. As I understand it, the show balanced four years of her work dealing with the repugnant principal Osgood Conklin (Gale Gordon), teaching some kids who were comically dumb, pining for her boyfriend, hunky biology teacher Phil Boynton (Robert Rockwell), to finally just goddamn propose to her already, and kvetching to her gossipy landlady Mrs. Davis (Jane Morgan) about all of the above. The movie does much the same thing, though in a more ambitious and compressed frame; it opens with Connie Brooks's arrival in town, blurs through anything from several months to several years in a whirlwind, and then lands on most of its actual plotlines, circling around the tortured politicking by which Conklin convinces Connie to support his bid to be made district superintendent in exchange for his promise to make Phil the new principal at Madison, thus clearing the way for him to finally be able to afford to pop the question. Meanwhile, Connie is tutoring the bright but lazy and underperforming Gary Nolan (Nick Adams), son of newspaper magnate Lawrence Nolan (Don Porter), one of the richest men in town. And Lawrence is quite taken with Connie's sardonic spunkiness, and he's much less reluctant to show it than Phil has been after all this time dating.

Two thoughts: this leaves us with another possible explanation for the movie: it's a wraparound prequel and finale to the show, but one which is enabled to function as a complete standalone narrative because the prequel elements do a fine job setting up all the characters and situations (it is, in fact, maybe the only TV series adapted into a movie with the same cast by the same creators I've seen that doesn't feel like it's trading on the viewer's knowledge of the show whatsoever; and this despite being a big hit when there were only three networks). And in this it is not merely the first of its kind, but maybe also the only one.

The other thought: golly gee whiz, the '50s, huh? It's not the only decade in American cinema where the motivating force behind the plot would be the female lead conniving to get her boyfriend a higher paying position so he could afford to propose to her so she could quit a job she was good at and enjoyed. But it's probably the decade where it doesn't seem that there could have been any other option. It's easy to get hung up on that kind of thing, and not very edifying intellectually, but still, it makes for an extraordinarily weird viewing experience; so heavily invested in the most reactive kind of Eisenhower Era social conservatism that one starts to wonder if the thing to do is regard it as some manner of deliberate camp. It can't really be that, of course. It definitely triggers our emotional responses in straightforward ways that assume that yes, we can't think of a better task for an adult woman with talent as a schoolteacher than to be constantly on a man hunt.

It does everything pretty straightforwardly, for that matter. The creative leads, director and co-writer Al Lewis, and co-writer Joseph Quillan, were both primarily veterans of TV - of Our Miss Brooks itself, naturally - and while the statement "this theatrical motion picture looks and feels like an episode of television" no longer has quite the same bite in 21st Century, back in '56, there's pretty much no upshot to that criticism. Our Miss Brooks has a crew who came mostly out of the movies, including Oscared cinematographer Joseph LaShelle and producer David Weisbart, a year after he oversaw Rebel Without a Cause, and all combined, they're just about able to force a kind of cinematic visual scale onto the material that balances out, if not exactly compensates for, the grimly by-the-numbers screenwriting. This is not the kind of comedy that startles you and catches you off guard; it is the kind for which the set-up for future gags is done that an even slightly savvy viewer will be able to map out the exact timing of the jokes sometimes whole scenes in advance. It is possible that this is what a half-century of sitcom evolution does for us, and viewers in '56 would have been quite absorbed by the comic shenanigans before them. But that requires assuming that World War II made everybody so stupid that they'd forgotten about comedy in the '30s.

This is, then, sitcom humor: big, broad, obvious sitcom humor. Stating that feels less like an insult than a simple definition. The weird thing about the movie, though, is that it's doofy comedy doesn't seem to matter really. There's nothing bigger, or broader, or more obvious in the film than Arden's mugging - she pulls faces like the bronze medalist at a Harpo Marx competition, wheeling her head around to grimace and bug out every one of her features simultaneously, somehow, to let us know exactly how mortified Connie is by the obviousness and venality of all the people she interacts with on a daily basis. It's not "acting" quite as much as it is "pantomime". And yet, while being the most conspicuously unhinged thing to be found onscreen, Arden is also clearly the film's saving grace. Her cartoon exaggerations, entirely out of proportion to the mild japery that goes on, push the film into a weirdly subjective realm, in which we find ourselves plugging through the constant bombardment of petty indignities that our Miss Brooks has to suffer through right along with her.

It provides an inexplicable tether of emotional honesty to a tossed-off lark that registers as a comedy more because of its happy lack of substance than because anything within it is particularly funny - comedy being subjective and all, I still don't feel even a little bit guilty about how much I wasn't laughing nor being tempted to laugh throughout the movie. It's tremendously easy to like Connie Brooks, to find her opponents offensive and her lovers frustratingly obtuse, simply because Arden has such an easy way of falling into the character's clownish beats, and make them feel comfortable. That's the TV connection, I have no doubt: even without trading on the viewer's relationship with the show (which was entirely nonexistent, for this viewer), it trades on the performers' relationship with the show, and the acting shorthand and fully worked-out personality that the performers have built. Our Miss Brooks is rather plain-looking cinema, and rote storytelling, and I doubt I'll have concrete memories of it a year from now. And yet, in the moment of watching it, Arden and some of her costars (not, unfortunately, Rockwell, a terribly uninvolving romantic lead) present characters who've been sharply-etched to the point that it's easy to get invested in watching them even if what they're doing isn't particularly interesting. That's a bizarre half-triumph, but it's far more than I expected when I started the movie or even during its pokey opening ten minutes, and I find myself fondly disposed towards Our Miss Brooks despite the paucity of things I can point to and state, firmly, "oh, I liked that." Television is just weird that way.

Categories: comedies, movies about teachers, romcoms