Max overdrive

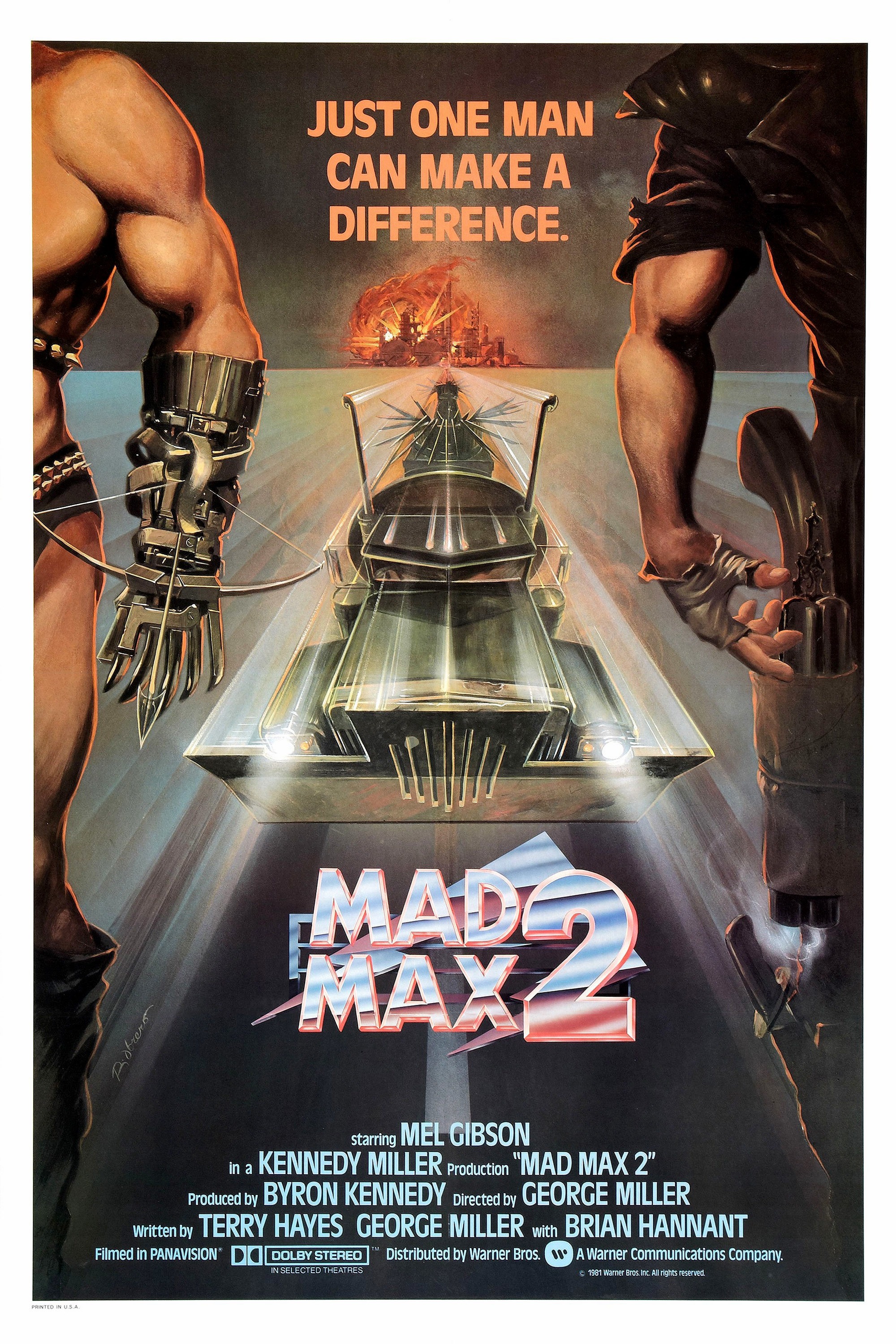

Mad Max 2 is, maybe, the perfect sequel. And if you'll let me pause on that very ebullient sentiment, a note on usage. The film is known by that title everywhere in the world except for North America; the original Mad Max had received a virtually invisible release in 1980, the victim of immensely poor timing, with its distributor American International Pictures in its final death throes at exactly the same time. When Warner Bros. prepared to release the sequel into the United States in 1982, the company (correctly) felt that marketing the film as a sequel to a movie that few people had heard of and fewer had actually seen would be commercial suicide, and so they retitled it, based on the film's dialogue. It was called, in the States, The Road Warrior, and that is how those of us who grew up in the States have learned its name. Including the present author, though I've only ever actually watched the film in prints that show the title as Mad Max 2 (the currently in-print DVD and Blu-ray have it as such). But that is not the reason I shall hereafter refer to the movie as The Road Warrior; I have far more boring pragmatic reasons. Mad Max and Mad Max 2 look very similar; Mad Max and The Road Warrior can be quickly distinguished and leave no room for any confusion. So now we can comfortably talk about the thing.

As I was saying, The Road Warrior is surely the perfect sequel. Structurally and as a story, it follows logically on from the circumstances of Mad Max, but it is entirely self-contained in its arcs, and can be readily appreciated with no more background than that provided in an opening montage including some footage from the earlier film (as is neatly attested to by the film becoming a hit Stateside and a star-making vehicle in the American film industry for Mel Gibson, despite most Americans having no clue what went on in Mad Max). It greatly expands upon the world established in the first film without any contradiction; it replicates the elements of the first movie that were most successful without simply repeating them. It is both "more of Mad Max", and "more than Mad Max", as beautiful an example of a filmmaker getting to do more of the same thing only with more resources and experience and as a result creating something that's better in almost every way than its predecessor (we'll get to the hedge in that "almost" soon enough).

In fact, The Road Warrior is such a perfect sequel that it also happens to be damn close to a perfect movie in and of itself. At any rate, I'd have a hard time scrounging up anything that's wrong with it; where it has limitations in its character writing and acting, it patches over them with its very particular tone, and it has not other limitations that I can speak of. And it is surely the single best post-apocalyptic movie ever made - and in its wake, there were a shit-ton of post-apocalyptic movies that copied its "leather daddies in the desert" aesthetic without a tenth of the inspiration or success - and as much respect as we should give to the exemplar of any genre, that happens to be one for which I have totally disproportionate affection anyway.

The film starts with a series of impressionistic snatches of imagery from Mad Max, from the end of The Road Warrior, and from news reels, with an aged narrator (Harold Baigent) recalling how all the civilisations in the world collapsed following a global war which avoided using nuclear weaponry (that favorite crutch of the post-apocalypse set), but still managed to leave the world in a pile of shit, by tapping all the resources available. In the short term, that led to the sagging, tired Australia of Mad Max. In the long term, even the spare framework of industrial civilisation remaining in that film has rotted away, and the machines left behind by the world's collapse have become the fetish objects of the humans left. And since a car in the desert is nothing but an immobile oven if you can't make it run, the meager resources of gasoline still remaining have turned into the most precious substance in the Outback. It's in this world that our narrator positions Max (Gibson), "a shell of a man; a burned-out, desolate man". He is the Road Warrior, a spirit of loss and tragedy roaming the wasteland until he has boiled away the last of his self. And so, before it even starts its plot, The Road Warrior has already overleapt its predecessor to become an honest-to-God myth; we are positioned decades after the events we're about to watch unfold, and invited to think of the film as a legend happening in real time. That's the definitive difference between this film and Mad Max, and it entirely favors the sequel.

The unfolding legend finds Max fleeing in the Last of the V-8 Interceptors from a gang of motorcycle hooligans who, like him, are scavenging fuel from anyplace they can find it; unlike him, they're willing to kill people to do it. The particular hooligan that especially causes Max difficulty is Wex (Vernon Wells), a mohawked psycho who keeps his slave and presumable lover (Jimmy Brown) chained to him; and while Max is able to endeavor to have a nasty-looking dart hit Wez in the arm, it only slows the biker down and sends him back to home base. In the meantime, Max's explorations of the desert scrub lead him to a trap set by a gangly, demented gyro captain (Bruce Spence), who also shows a marked willingness to ambush innocents for the fuel to power his currently dead autogyro, but Max takes virtually no time to turn the tables on his attacker. The gyro captain bargains for his life with some valuable knowledge: not very far away, there's a colony of relative pacifists living on a functioning oil refinery. Max immediately sets off, and finds the same gang which Wez belongs to attacking a pair of the refinery's residents; he's able to keep one of them alive just long enough to take him back on the promise that the man's life will be Max's bargaining chip to get some precious, precious fuel. The colony leader, Pappagallo (Mike Preston), has no interest in dealing with this stranger, but there are bigger problems: the gang, under the leadership of the Lord Humungus (Kjell Nilsson), has been attacking the refinery regularly, and the latest of those attacks is about to kick in. A feral boy (Emil Minty), who has taken a shine to Max, exacerbates the situation by killing Wez's slave with a sharpened boomerang, and with war about to break out, Max cuts a new deal, to help the refinery colonists escape Humungus's onslaught. And while the cold calculations of all involved don't seem to imply it, we can assume that the narrator's opening promise that Max's journeys through the wasteland led to the restoration of his humanity is going to kick in sometime through his attempts to save the colony.

I've made that seem more complicated than it is, but that's part of the joy of The Road Warrior: getting lost in the pile-up of details in story. It is, after all, an act of storytelling, presented explicitly as such in the opening moments, and the tone follows through on that consistently. Half of the cast has completely functional names - Gyro Captain, Feral Kid, Warrior Woman (Virginia Hey), the Toadie (Max Phipps) - and everybody in the cast plays their roles with a sort of detached superficiality; there's no room to dig into these characters' inner lives, because they are very self-consciously pitched as larger-than-life concepts in a larger-than-life mythic adventure that takes place in one of the most convincing fantastical settings in the movies, if the dehydrated post-war world on display can count as "fantastical".

It's quite a visual world, expressed as much in the costuming (by Norma Moriceau) and art direction (by Graham "Grace" Walker) as in the script - when I call this the best post-apocalypse movie ever made, what I'm largely thinking about is how thoughtfully it absorbs the nature of that apocalypse into its world and spits it out in the form of little details that are presented without any real comment, but matter deeply. The cobbled-together outfits and the reclaimed-garbage nature of many of the props and vehicles speaks to an entire society based on scavenging what still works from the old world and adapting it to the new; the whole film is so compellingly about the way that life might function in a post-industrial desert world, far more than any other film I can name. We are never, ever told what the rules are, of anything - not the gang's theatrical way of dressing (Humungus wears something that looks like a hockey mask designed to resemble the visor from a medieval helmet), not the codes of honor that guide Max and Pappagallo's interactions. And some of it never becomes clear; but much of it we can pick up, just by paying close attention to the way things are shot and how people behave. The best example I can think of is the way the film deals with ammunition: the Humungus has a fancy case with his ridiculously convoluted gun, and just five bullets - we don't need a single word of dialogue to understand that each of those bullets is used with the most reluctant care. Or when Max is given the gift of two shotgun shells, and we grasp what a profound thank-you this represents.

When it takes time away from world-building and myth-spinning, The Road Warrior is also an action movie, and this is that one single place I mentioned where it's not an improvement on Mad Max. There simply isn't as much action to go around. The first movie is a kaleidoscopic marvel of car chases staged with imagination and recklessness like the world had never seen; the sequel only really has one actual car chase to speak of, with a few smaller sequences that are over and done so quickly that they don't even deserve the name "setpieces". That one actual car chase is a fucking dream, though; a protracted climax that involves a small army of car chasing a tanker and another small army defending it, with people clambering on the outside of vehicles obviously tearing ass down the Australian highways, as Brian May's score urgently blasts from the soundtrack. It's a triumph of scale and knowing exactly the way to cut between individual moments within a huge tapestry of moving parts; between this and the similarly wide-ranging truck race in the back half of Raiders of the Lost Ark, I am fully inclined to call 1981 the year of Peak Car Chase.

Even if he doesn't have quite as much desire to show off radically inventive action sequences, though, director George Miller's enormous jump in talent from the last film means that the whole movie has the humming tension that Mad Max only enjoyed in its best moments. It's a terrifically confident piece of filmmaking, from the biggest strokes - Miller and cinematographer Dean Semler using the horizon line to slice the frame between sky and land in the most dramatic way possible to emphasise the desolation of their locations - down to the most immodestly little details, like the single white frame that flashes up when Wez headbutts one of the colonists, an almost boringly minute notion that makes that action have vastly more impact than it might otherwise. I cannot imagine how to make The Road Warrior a better version of itself: a drama of the brutality it takes to survive a merciless environment, filtered through memory, nostalgia, and the encoding of history into narrative forms. This is basically perfect cinema, using every cut, every piece of visual information, and every line of dialogue to guide us towards its unexpectedly rich broad-strokes storytelling and exhilarating triumph of decency over cynicism and cruelty (it is, in fact, a direct refutation of the nihilism of Mad Max). Out of the countless action movies produced in the 1980s, there only a few genuine works of art; and The Road Warrior might very well be the best of that extremely rarefied company.

Reviews in this series

Mad Max (Miller, 1979)

Mad Max 2 AKA The Road Warrior (Miller, 1981)

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (Miller and Ogilvie, 1985)

Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller, 2015)

As I was saying, The Road Warrior is surely the perfect sequel. Structurally and as a story, it follows logically on from the circumstances of Mad Max, but it is entirely self-contained in its arcs, and can be readily appreciated with no more background than that provided in an opening montage including some footage from the earlier film (as is neatly attested to by the film becoming a hit Stateside and a star-making vehicle in the American film industry for Mel Gibson, despite most Americans having no clue what went on in Mad Max). It greatly expands upon the world established in the first film without any contradiction; it replicates the elements of the first movie that were most successful without simply repeating them. It is both "more of Mad Max", and "more than Mad Max", as beautiful an example of a filmmaker getting to do more of the same thing only with more resources and experience and as a result creating something that's better in almost every way than its predecessor (we'll get to the hedge in that "almost" soon enough).

In fact, The Road Warrior is such a perfect sequel that it also happens to be damn close to a perfect movie in and of itself. At any rate, I'd have a hard time scrounging up anything that's wrong with it; where it has limitations in its character writing and acting, it patches over them with its very particular tone, and it has not other limitations that I can speak of. And it is surely the single best post-apocalyptic movie ever made - and in its wake, there were a shit-ton of post-apocalyptic movies that copied its "leather daddies in the desert" aesthetic without a tenth of the inspiration or success - and as much respect as we should give to the exemplar of any genre, that happens to be one for which I have totally disproportionate affection anyway.

The film starts with a series of impressionistic snatches of imagery from Mad Max, from the end of The Road Warrior, and from news reels, with an aged narrator (Harold Baigent) recalling how all the civilisations in the world collapsed following a global war which avoided using nuclear weaponry (that favorite crutch of the post-apocalypse set), but still managed to leave the world in a pile of shit, by tapping all the resources available. In the short term, that led to the sagging, tired Australia of Mad Max. In the long term, even the spare framework of industrial civilisation remaining in that film has rotted away, and the machines left behind by the world's collapse have become the fetish objects of the humans left. And since a car in the desert is nothing but an immobile oven if you can't make it run, the meager resources of gasoline still remaining have turned into the most precious substance in the Outback. It's in this world that our narrator positions Max (Gibson), "a shell of a man; a burned-out, desolate man". He is the Road Warrior, a spirit of loss and tragedy roaming the wasteland until he has boiled away the last of his self. And so, before it even starts its plot, The Road Warrior has already overleapt its predecessor to become an honest-to-God myth; we are positioned decades after the events we're about to watch unfold, and invited to think of the film as a legend happening in real time. That's the definitive difference between this film and Mad Max, and it entirely favors the sequel.

The unfolding legend finds Max fleeing in the Last of the V-8 Interceptors from a gang of motorcycle hooligans who, like him, are scavenging fuel from anyplace they can find it; unlike him, they're willing to kill people to do it. The particular hooligan that especially causes Max difficulty is Wex (Vernon Wells), a mohawked psycho who keeps his slave and presumable lover (Jimmy Brown) chained to him; and while Max is able to endeavor to have a nasty-looking dart hit Wez in the arm, it only slows the biker down and sends him back to home base. In the meantime, Max's explorations of the desert scrub lead him to a trap set by a gangly, demented gyro captain (Bruce Spence), who also shows a marked willingness to ambush innocents for the fuel to power his currently dead autogyro, but Max takes virtually no time to turn the tables on his attacker. The gyro captain bargains for his life with some valuable knowledge: not very far away, there's a colony of relative pacifists living on a functioning oil refinery. Max immediately sets off, and finds the same gang which Wez belongs to attacking a pair of the refinery's residents; he's able to keep one of them alive just long enough to take him back on the promise that the man's life will be Max's bargaining chip to get some precious, precious fuel. The colony leader, Pappagallo (Mike Preston), has no interest in dealing with this stranger, but there are bigger problems: the gang, under the leadership of the Lord Humungus (Kjell Nilsson), has been attacking the refinery regularly, and the latest of those attacks is about to kick in. A feral boy (Emil Minty), who has taken a shine to Max, exacerbates the situation by killing Wez's slave with a sharpened boomerang, and with war about to break out, Max cuts a new deal, to help the refinery colonists escape Humungus's onslaught. And while the cold calculations of all involved don't seem to imply it, we can assume that the narrator's opening promise that Max's journeys through the wasteland led to the restoration of his humanity is going to kick in sometime through his attempts to save the colony.

I've made that seem more complicated than it is, but that's part of the joy of The Road Warrior: getting lost in the pile-up of details in story. It is, after all, an act of storytelling, presented explicitly as such in the opening moments, and the tone follows through on that consistently. Half of the cast has completely functional names - Gyro Captain, Feral Kid, Warrior Woman (Virginia Hey), the Toadie (Max Phipps) - and everybody in the cast plays their roles with a sort of detached superficiality; there's no room to dig into these characters' inner lives, because they are very self-consciously pitched as larger-than-life concepts in a larger-than-life mythic adventure that takes place in one of the most convincing fantastical settings in the movies, if the dehydrated post-war world on display can count as "fantastical".

It's quite a visual world, expressed as much in the costuming (by Norma Moriceau) and art direction (by Graham "Grace" Walker) as in the script - when I call this the best post-apocalypse movie ever made, what I'm largely thinking about is how thoughtfully it absorbs the nature of that apocalypse into its world and spits it out in the form of little details that are presented without any real comment, but matter deeply. The cobbled-together outfits and the reclaimed-garbage nature of many of the props and vehicles speaks to an entire society based on scavenging what still works from the old world and adapting it to the new; the whole film is so compellingly about the way that life might function in a post-industrial desert world, far more than any other film I can name. We are never, ever told what the rules are, of anything - not the gang's theatrical way of dressing (Humungus wears something that looks like a hockey mask designed to resemble the visor from a medieval helmet), not the codes of honor that guide Max and Pappagallo's interactions. And some of it never becomes clear; but much of it we can pick up, just by paying close attention to the way things are shot and how people behave. The best example I can think of is the way the film deals with ammunition: the Humungus has a fancy case with his ridiculously convoluted gun, and just five bullets - we don't need a single word of dialogue to understand that each of those bullets is used with the most reluctant care. Or when Max is given the gift of two shotgun shells, and we grasp what a profound thank-you this represents.

When it takes time away from world-building and myth-spinning, The Road Warrior is also an action movie, and this is that one single place I mentioned where it's not an improvement on Mad Max. There simply isn't as much action to go around. The first movie is a kaleidoscopic marvel of car chases staged with imagination and recklessness like the world had never seen; the sequel only really has one actual car chase to speak of, with a few smaller sequences that are over and done so quickly that they don't even deserve the name "setpieces". That one actual car chase is a fucking dream, though; a protracted climax that involves a small army of car chasing a tanker and another small army defending it, with people clambering on the outside of vehicles obviously tearing ass down the Australian highways, as Brian May's score urgently blasts from the soundtrack. It's a triumph of scale and knowing exactly the way to cut between individual moments within a huge tapestry of moving parts; between this and the similarly wide-ranging truck race in the back half of Raiders of the Lost Ark, I am fully inclined to call 1981 the year of Peak Car Chase.

Even if he doesn't have quite as much desire to show off radically inventive action sequences, though, director George Miller's enormous jump in talent from the last film means that the whole movie has the humming tension that Mad Max only enjoyed in its best moments. It's a terrifically confident piece of filmmaking, from the biggest strokes - Miller and cinematographer Dean Semler using the horizon line to slice the frame between sky and land in the most dramatic way possible to emphasise the desolation of their locations - down to the most immodestly little details, like the single white frame that flashes up when Wez headbutts one of the colonists, an almost boringly minute notion that makes that action have vastly more impact than it might otherwise. I cannot imagine how to make The Road Warrior a better version of itself: a drama of the brutality it takes to survive a merciless environment, filtered through memory, nostalgia, and the encoding of history into narrative forms. This is basically perfect cinema, using every cut, every piece of visual information, and every line of dialogue to guide us towards its unexpectedly rich broad-strokes storytelling and exhilarating triumph of decency over cynicism and cruelty (it is, in fact, a direct refutation of the nihilism of Mad Max). Out of the countless action movies produced in the 1980s, there only a few genuine works of art; and The Road Warrior might very well be the best of that extremely rarefied company.

Reviews in this series

Mad Max (Miller, 1979)

Mad Max 2 AKA The Road Warrior (Miller, 1981)

Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (Miller and Ogilvie, 1985)

Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller, 2015)