Childhood dreams

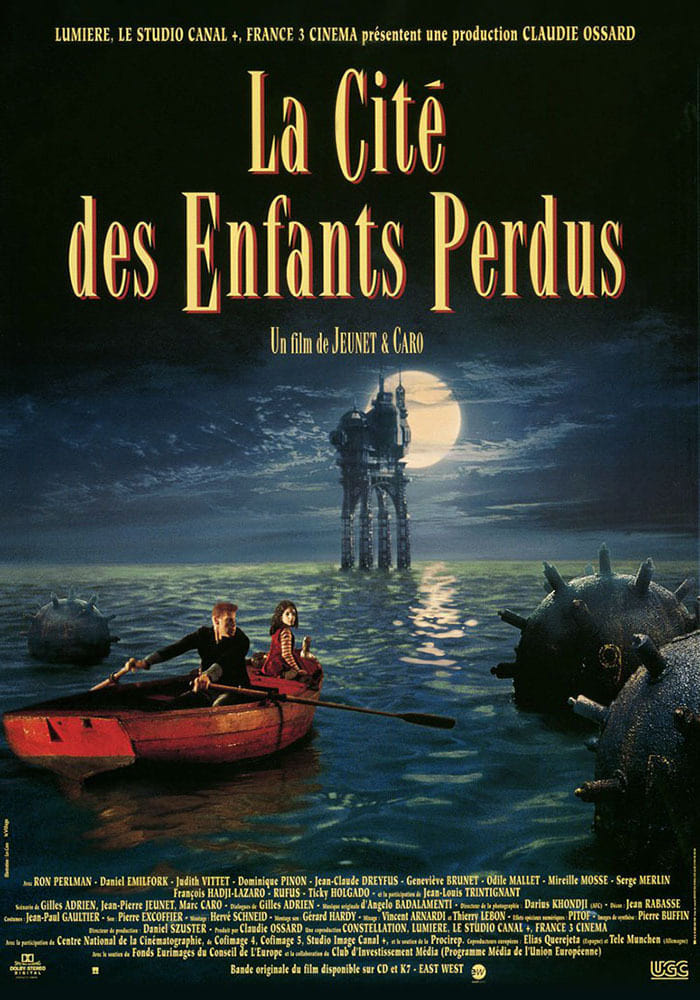

A review requested by Vianney B, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser. This was the opening film of the 48th Cannes International Film Festival, on 17 May, 1995 - more on the 1995 Cannes Festival project.

The two biggest problems with 1995's The City of Lost Children are that Delicatessen came out before it, and Amélie came out after it. And I concede that this is the least-fair way to go about the business of film criticism, but it's still hard to shake the sense that everything the film does well - and it does many things well - other films by the members of its directing team also do, as well or better (it's also heavily indebted to Terry Gilliam's Brazil, but if we're going to start shitting on all the movies that crib from Brazil, we might as well not even bother having movies with production design).

The film is the second and last movie directed by Marc Caro & Jean-Pierre Jeunet, before the lure of Hollywood's Alien: Resurrection drew Jeunet to America and broke up the team (though Caro did help with the visual design of that film). And while the thinness of animator & comic book artist Caro's film career in the 20 years since leads a lot of us into the habit of acting like there's a straight line between this and the rest of Jeunet's career, that's a mistake, particularly in this case. There's a profound tonal difference between Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children on the one hand, and everything Jeunet made by himself on the other. A kind of nightmare veneer covers the first two, not in the sense that the films are horrifying or disturbing, but that they present places which feel mean and dangerous in ways that can be neither predicted nor redirected. While Jeunet's solo work is more boisterous, carnivalesque, and sentimental; even his Alien film is more chipper and upbeat than Delicatessen, a pitch black comedy about cannibalism, or City of Lost Children, a movie about a child kidnapping ring whose plot leaps around in such arbitrary bursts that it comes close to Surrealism, the aggressive sort where we're meant to be in a constant state of mental disarray while we're watching it.

What can never be said is that it's not exactly the film that Caro and Jeunet intended for it to be, or at least so I assume. There are no moments in The City of Lost Children that feel accidental, and the film's mise en scène is so hermetically sealed off that every single thing we see onscreen has to be regarded as a deliberate choice. The result is a movie that is first and foremost an exercise in design. Not just the production design, by Caro and Jean Rabasse, though it is impossible to see the movie and not first notice this; nor the character design, and it does seem that "character design" is the more correct term to use than "costumes and makeup", given how much the film starts from the ground and goes up in making its human figures feel like extensions of the world they inhabit, with Jean-Paul Gaultier's striking costumes defining the shape of the wearers as line objects, growing out of the lines of the set design and erupting in the comic grotesques of the faces of all the characters in the story. I swear it's not just knowing Caro's background in cartooning that leads me to suggest that The City of Lost Children resembles French comics come to life; not the soft, kid-friendly kind like Asterix, but the more graphically sleek and otherworldly sort drawn by artists like Moebius.

It's this sense, that the film has been assembled according to the principles of graphic art rather than movie directing, that most sets The City of Lost Children apart from all the movies I started off by comparing it to, and makes it a genuinely important film to hunt out and watch. It feels like concept art come to life, in way that's arresting and genuinely exciting to look at. But you'll notice that other than the phrase"kidnapping ring", I haven't said a word about the plot, and other than vague handwaving about the way it subscribes the narrative logic of a nightmare, nothing about the way it feels. Which is exactly "the problem", though I don't know that the movie labors on believing that this is something it's doing wrong. Still, it's the reason that I prefer Delicatessen, with its clear command of tone throughout, and its straightforward narrative development, or Amélie, which in some ways is just as self-contained as The City of Lost Children, but is light and sweet-natured enough that it doesn't seem so locked away from us as viewers. There's a story here, written by the directors & Gilles Adrien, and it's even a bit of a complicated one that's interesting to follow with, even though it doesn't really make sense until the last thirty minutes or so start to provide the whys behind all these weird beings we've been following. The approximate shape of it is that there's an oil rig outside of a port town, and on this rig lives Krank (Daniel Emilfork), a balding mad scientist who's all lab coat and gangly limbs, the little woman Mlle. Bismuth (Mireille Mossé), six dimwitted clones (all played by Dominique Pinon, who has been in every one of Jeunet's films), and Uncle Irving, a brain in a tank (voiced by Jean-Louis Trintignant). Krank has been kidnappign children from the town to steal their dreams, and one of his latest acquisitions is the adopted brother of One (Ron Perlman, speaking French phonetically), a strongman who sets himself to the task of finding the lost children, aided by the little girl Miette (Judith Vittet), an escapee from a ring of orphan thieves controlled by a cruel pair of conjoined twins (Geneviève Brunet and Odile Mallet).

Straightforward enough, though the way the story develops is so heavily based in innuendo and mysteries that don't pay off for half the running time that it's all much more of a "just go along for the ride" experience than it sounds. It's the kind of film that doesn't make the smallest attempt to win you over to its side; if you aren't immediately grabbed by the demented look of its world, there's nothing in the first ten minutes that's going to convince you to stick with it. And this is by no means a world that tries to be inviting: it's made up suffocatingly close buildings that all feel like they're about to collapse and villains who are queasily bio-mechanical, like the abandoned concepts from a David Cronenberg children's film. Darius Khondji shoots all of it in a patina of mouldering greens that makes even the decayed look of his other 1995 film, Se7en, seem cheery. Now, I happen to find the look of the film utterly captivating, even as I wish that the film attached to that look had a bit more oxygen. If the visuals don't work for the individual, then the whole thing is done: Delicatessen is a better nightmare, even if it's less audaciously visual, and the visceral reactions it provokes are more sustained. Still, there are so many utterly unforgettable images here - the storybook illustration feeling of the sea and the oil rig, the flea's-eye view of the damp alleys of the town, the opening scene in which the clones stage a travesty of Christmas to attempt to cheer up the child they're kidnapping - that I'd still have to urge the movie on everybody I could. It's not always successful at being a thoroughly sui generis demented dreamscape and bedtime story bone dark, but it always tries to be, and that kind of unrestrained commitment is a precious thing.

The two biggest problems with 1995's The City of Lost Children are that Delicatessen came out before it, and Amélie came out after it. And I concede that this is the least-fair way to go about the business of film criticism, but it's still hard to shake the sense that everything the film does well - and it does many things well - other films by the members of its directing team also do, as well or better (it's also heavily indebted to Terry Gilliam's Brazil, but if we're going to start shitting on all the movies that crib from Brazil, we might as well not even bother having movies with production design).

The film is the second and last movie directed by Marc Caro & Jean-Pierre Jeunet, before the lure of Hollywood's Alien: Resurrection drew Jeunet to America and broke up the team (though Caro did help with the visual design of that film). And while the thinness of animator & comic book artist Caro's film career in the 20 years since leads a lot of us into the habit of acting like there's a straight line between this and the rest of Jeunet's career, that's a mistake, particularly in this case. There's a profound tonal difference between Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children on the one hand, and everything Jeunet made by himself on the other. A kind of nightmare veneer covers the first two, not in the sense that the films are horrifying or disturbing, but that they present places which feel mean and dangerous in ways that can be neither predicted nor redirected. While Jeunet's solo work is more boisterous, carnivalesque, and sentimental; even his Alien film is more chipper and upbeat than Delicatessen, a pitch black comedy about cannibalism, or City of Lost Children, a movie about a child kidnapping ring whose plot leaps around in such arbitrary bursts that it comes close to Surrealism, the aggressive sort where we're meant to be in a constant state of mental disarray while we're watching it.

What can never be said is that it's not exactly the film that Caro and Jeunet intended for it to be, or at least so I assume. There are no moments in The City of Lost Children that feel accidental, and the film's mise en scène is so hermetically sealed off that every single thing we see onscreen has to be regarded as a deliberate choice. The result is a movie that is first and foremost an exercise in design. Not just the production design, by Caro and Jean Rabasse, though it is impossible to see the movie and not first notice this; nor the character design, and it does seem that "character design" is the more correct term to use than "costumes and makeup", given how much the film starts from the ground and goes up in making its human figures feel like extensions of the world they inhabit, with Jean-Paul Gaultier's striking costumes defining the shape of the wearers as line objects, growing out of the lines of the set design and erupting in the comic grotesques of the faces of all the characters in the story. I swear it's not just knowing Caro's background in cartooning that leads me to suggest that The City of Lost Children resembles French comics come to life; not the soft, kid-friendly kind like Asterix, but the more graphically sleek and otherworldly sort drawn by artists like Moebius.

It's this sense, that the film has been assembled according to the principles of graphic art rather than movie directing, that most sets The City of Lost Children apart from all the movies I started off by comparing it to, and makes it a genuinely important film to hunt out and watch. It feels like concept art come to life, in way that's arresting and genuinely exciting to look at. But you'll notice that other than the phrase"kidnapping ring", I haven't said a word about the plot, and other than vague handwaving about the way it subscribes the narrative logic of a nightmare, nothing about the way it feels. Which is exactly "the problem", though I don't know that the movie labors on believing that this is something it's doing wrong. Still, it's the reason that I prefer Delicatessen, with its clear command of tone throughout, and its straightforward narrative development, or Amélie, which in some ways is just as self-contained as The City of Lost Children, but is light and sweet-natured enough that it doesn't seem so locked away from us as viewers. There's a story here, written by the directors & Gilles Adrien, and it's even a bit of a complicated one that's interesting to follow with, even though it doesn't really make sense until the last thirty minutes or so start to provide the whys behind all these weird beings we've been following. The approximate shape of it is that there's an oil rig outside of a port town, and on this rig lives Krank (Daniel Emilfork), a balding mad scientist who's all lab coat and gangly limbs, the little woman Mlle. Bismuth (Mireille Mossé), six dimwitted clones (all played by Dominique Pinon, who has been in every one of Jeunet's films), and Uncle Irving, a brain in a tank (voiced by Jean-Louis Trintignant). Krank has been kidnappign children from the town to steal their dreams, and one of his latest acquisitions is the adopted brother of One (Ron Perlman, speaking French phonetically), a strongman who sets himself to the task of finding the lost children, aided by the little girl Miette (Judith Vittet), an escapee from a ring of orphan thieves controlled by a cruel pair of conjoined twins (Geneviève Brunet and Odile Mallet).

Straightforward enough, though the way the story develops is so heavily based in innuendo and mysteries that don't pay off for half the running time that it's all much more of a "just go along for the ride" experience than it sounds. It's the kind of film that doesn't make the smallest attempt to win you over to its side; if you aren't immediately grabbed by the demented look of its world, there's nothing in the first ten minutes that's going to convince you to stick with it. And this is by no means a world that tries to be inviting: it's made up suffocatingly close buildings that all feel like they're about to collapse and villains who are queasily bio-mechanical, like the abandoned concepts from a David Cronenberg children's film. Darius Khondji shoots all of it in a patina of mouldering greens that makes even the decayed look of his other 1995 film, Se7en, seem cheery. Now, I happen to find the look of the film utterly captivating, even as I wish that the film attached to that look had a bit more oxygen. If the visuals don't work for the individual, then the whole thing is done: Delicatessen is a better nightmare, even if it's less audaciously visual, and the visceral reactions it provokes are more sustained. Still, there are so many utterly unforgettable images here - the storybook illustration feeling of the sea and the oil rig, the flea's-eye view of the damp alleys of the town, the opening scene in which the clones stage a travesty of Christmas to attempt to cheer up the child they're kidnapping - that I'd still have to urge the movie on everybody I could. It's not always successful at being a thoroughly sui generis demented dreamscape and bedtime story bone dark, but it always tries to be, and that kind of unrestrained commitment is a precious thing.