Riding alone together

All of Zhang Yimou's films, even his recent martial arts epics, are ultimately intimate stories about the individual set in contrast to society. Not necessarily in opposition; but Zhang's films usually explore the ways in which social animals are forced to behave in isolation.

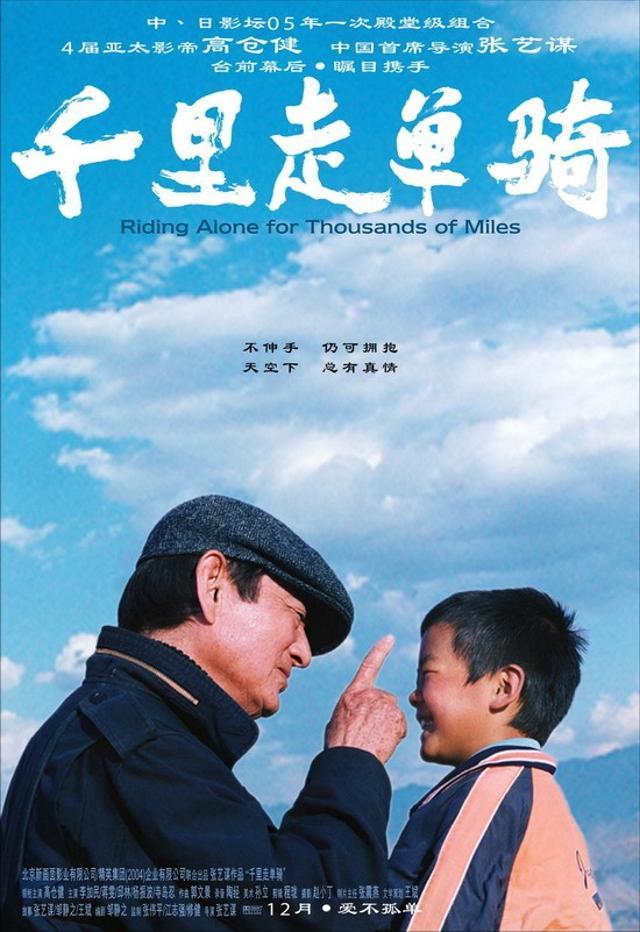

This has never been more apparent than in his latest film Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles, in which the hero is a stranger in a land where he knows neither the customs, nor the bureaucracy, nor the government. Takata Gou-ichi is an elderly Japanese fisherman whose estranged son Ken-ichi is dying. In a desparate attempt to reconnect before it is too late, Takata journeys to China, to finish his son's project of filming traditional folk mask operas.

The film operates on multiple intertwining levels, and to pick apart how they work together is necessarily to recount the experience of watching. In brief, there is the story of a man who enters a world he does not understand and cannot function in, not because of love but because of its specific absence, and the desire to rebuild. There is the story of universal emotions and particularly the bonds of fatherhood, leading others to understand and help that man - most of the second half concerns Takata's attempt to reunite the abandonded son of an opera singer with his father. And there is a celebration of Chinese culture, past and present; the traditional opera remaining vital in a world of forms and departments, and even that communist snarl is treated on lovingly, as though Zhang takes pride in the formal elegance that it gives to everyday life.

All of these meanings come together in the title, which can be understood literally (it is also the name of the opera that Takata wishes to shoot), sincerely (Takata's linguistic and cultural isolation), or ironically (despite his isolation, Takata is surrounded by support and understanding), changing as the film requires. The success of the film lies in taking these different programmatic meanings, and effortlessly blending them. The mixture here of the social and cultural with the private and foreign is truly remarkable.

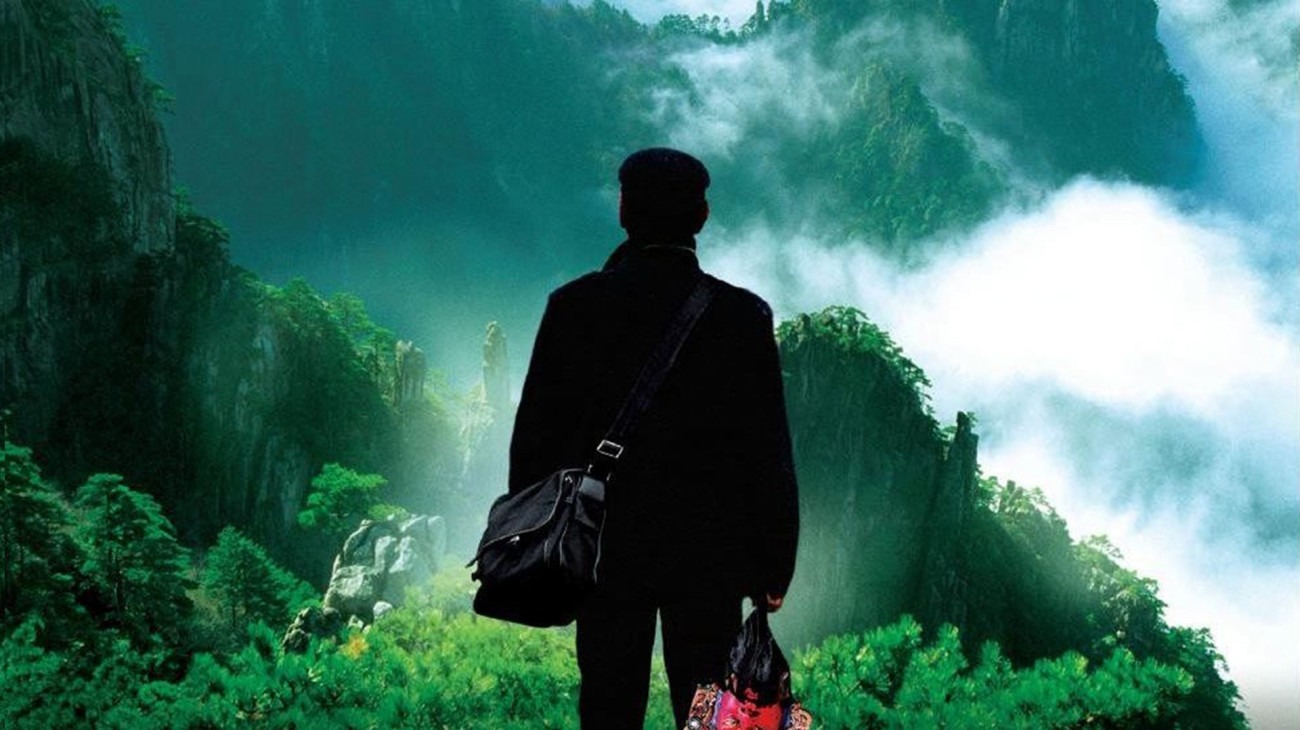

Zhang is famously a great camera director, and his work with cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding (of House of Flying Daggers) is nothing shy of masterful. The primary motif of the film is segregation: using the frame to cut Takata out from the society around him, using lines and doors within the frame, or in the most common and arresting image, simply setting him alone in a vast empty landscape, and allowing the very width of the frame to show how lonely this man is.

Takakura Ken, the Japanese Clint Eastwood, plays Takata, and it is one of the great performances in recent memory. He gets his nickname from his stoic silence and granite face, and here he uses those features to express a lifetime of bottled-up emotions. Like a great actor from the silent age, Takakura can use his eyes to hint at feelings that are not even hinted at on his thin, tight mouth. As Takata's story moves through it's quiet tragedy, it is Takakura who makes us realise the cost.

Not all is well with the film; in particular it suffers greatly from Zhang's apparent doubt that we "get" it, and so the ending literalises the parallel between Takata and the opera singer's son. They share many lovely, tiny moments in the second half of the film, and it is nothing short of insulting that Takata has to verbalize what that means. It's a small note, but utterly false.

Still, it's one sour moment in an otherwise brilliant canvas. This is not Zhang's best work, but as a return to form it is thrilling and miraculous.

This has never been more apparent than in his latest film Riding Alone for Thousands of Miles, in which the hero is a stranger in a land where he knows neither the customs, nor the bureaucracy, nor the government. Takata Gou-ichi is an elderly Japanese fisherman whose estranged son Ken-ichi is dying. In a desparate attempt to reconnect before it is too late, Takata journeys to China, to finish his son's project of filming traditional folk mask operas.

The film operates on multiple intertwining levels, and to pick apart how they work together is necessarily to recount the experience of watching. In brief, there is the story of a man who enters a world he does not understand and cannot function in, not because of love but because of its specific absence, and the desire to rebuild. There is the story of universal emotions and particularly the bonds of fatherhood, leading others to understand and help that man - most of the second half concerns Takata's attempt to reunite the abandonded son of an opera singer with his father. And there is a celebration of Chinese culture, past and present; the traditional opera remaining vital in a world of forms and departments, and even that communist snarl is treated on lovingly, as though Zhang takes pride in the formal elegance that it gives to everyday life.

All of these meanings come together in the title, which can be understood literally (it is also the name of the opera that Takata wishes to shoot), sincerely (Takata's linguistic and cultural isolation), or ironically (despite his isolation, Takata is surrounded by support and understanding), changing as the film requires. The success of the film lies in taking these different programmatic meanings, and effortlessly blending them. The mixture here of the social and cultural with the private and foreign is truly remarkable.

Zhang is famously a great camera director, and his work with cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding (of House of Flying Daggers) is nothing shy of masterful. The primary motif of the film is segregation: using the frame to cut Takata out from the society around him, using lines and doors within the frame, or in the most common and arresting image, simply setting him alone in a vast empty landscape, and allowing the very width of the frame to show how lonely this man is.

Takakura Ken, the Japanese Clint Eastwood, plays Takata, and it is one of the great performances in recent memory. He gets his nickname from his stoic silence and granite face, and here he uses those features to express a lifetime of bottled-up emotions. Like a great actor from the silent age, Takakura can use his eyes to hint at feelings that are not even hinted at on his thin, tight mouth. As Takata's story moves through it's quiet tragedy, it is Takakura who makes us realise the cost.

Not all is well with the film; in particular it suffers greatly from Zhang's apparent doubt that we "get" it, and so the ending literalises the parallel between Takata and the opera singer's son. They share many lovely, tiny moments in the second half of the film, and it is nothing short of insulting that Takata has to verbalize what that means. It's a small note, but utterly false.

Still, it's one sour moment in an otherwise brilliant canvas. This is not Zhang's best work, but as a return to form it is thrilling and miraculous.