Summer of Blood: Horror in a Post-War World - Digital horror

Horror, in its broadest construction, has always been something of a faddish genre. There have been comedies and character dramas for as long as there have been movies, and depending on where you want to set the margins around "action movie", they've existed in some for or another for nearly as long. Horror, though, has its ebbs and flows, periods where it's driven mostly underground, periods where it has to hide out in the form of something else. In recent memory, for example, one of these periods was in the first half of the 1990s, which produced hardly any important works of horror in English that weren't trying desperately hard to be prestige dramas or invisible direct-to-video schlock. But the most protracted lull in American horror is the one that began after the bottom fell out of the horror market in the late '30s, after several years of studios big and small trying to chase Universal's genre-defining hits from early in that decade. It was a slow descent: for most of the war years, studio-made horror didn't vanish, so much as decline in importance, puttering along as program-filler cranked out by the B-film units at the mini-majors, Universal and RKO, while the Poverty Row studios kept the genre alive in the form cheap, tacky quickies. It wasn't until after war ended in 1945 that horror basically disappeared for several years at any meaningfully serious level - the Poverty Row folks never gave up on it, but what they made was strictly crap on a shoestring budget with almost invisible audience. We're going to peek in on what they were up to soon enough in this Summer of Blood.

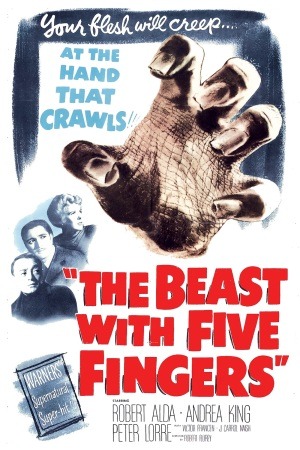

At the moment, let's spend a moment with what amounts the the last big studio attempt at horror in the 1940s: the 1946 Warner Bros. production The Beast with Five Fingers, which premiered at the tale end of that year (on Christmas Day, in fact), and had most of its run in 1947. It's an awkward fit of company identity and historical importance: Warner's was never one of the biggest players in the genre, and much of the film, especially its infamously stupid, winking ending, feels like a conscious attempt to distance the movie from its own content. Which is, as you can maybe guess from the title, a disembodied hand that murders people.

Among its efforts to not be quite so much about a disembodied hand, The Best with Five Fingers spends the largest part of its running time as a murder mystery stealing from the "old dark house" motif. Around the beginning of the 20th Century, American expatriate Francis Ingram (Victor Francen) lives in a grand old mansion outside of a small town in Italy. He's attended by, he thinks, his best friends and most trusted confidants: lawyer Duprex (David Hoffman) is obviously just there for the slightly batty rich client; secretary Hilary Cummins (Peter Lorre), 20 years in Ingram's employ, is interested solely in the access his position affords him to Ingram's impressive library of astrological arcana, with which Hilary hopes to reconstruct the great lost studies of the pseudoscience; nurse Julie Holden (Andrea King), brought on some while back to care for Ingram after he suffered a stroke that paralysed his right side, has since moved from "kind medical professional" to "borderline prisoner under the obsessive control of a selfish tyrant". That leaves only our hero, Bruce Conrad (Robert Alda), and he's nothing but a con-man: a genial, charismatic con-man introduced in the film's opening scene by fleecing American tourists out of $50 for some worthless fake antiques, and then offering up just enough flim-flam to local cop Ovidio Castanio (J. Carrol Naish) so that the officer can feel like he hasn't totally abandoned his professional ethics. So it's hard to imagine that he sees Ingram as anything but a friendly mark.

Even with these enormous caveats, these are Ingram's friends and confidantes, and they are the people he asks to attest in writing to his evident sanity as he prepares to put up a new will. That, of course, means that he's about to do, which happens by accident, it seems, as he falls down a flight of stairs in his wheelchair. And this is the start of everyone's woes: for Ingram's only relatives are a pair of the worst kind of shitty, entitled Americans, father Raymond Arlington (Charles Dingle) and son Donald (John Alvin), and when they learn that Ingram's mysterious new will named Julie as the sole heir to his estate, they smell a rat immediately. But shenanigans of that sort are soon going to be a rather small priority to anybody but the grasping asshole Arlingtons: cued by a light in the masoleum where Ingram was interred, the rest of the cast finds that the corpse has been desecrated, its left hand removed. And right around the same time, the house is filled with the mournful tones of a Bach piece that Bruce re-set to be performed with one hand, as a great favor to the frustrated, crippled pianist. Different characters leap to conclusions at different times: Hilary, who was almost strangled to death by Ingram's incredibly powerful left hand shortly before his death, is the first to be sure that the dead man's missing body part is now haunting the house, and the first strangulation murder would seem to bear him out.

At no point was The Beast with Five Fingers going to be an all-time classic work of cinema, but given the tenuous state of horror in 1946, it acquits itself beautifully. Screenwriter Curt Siodmak, one of the key voices at Universal during its shift in the '40s to B-horror, thought that putting the weird-looking, weird-sounding Lorre in the role of Hilary broke the tension a bit too much, but frankly, Lorre is the best thing the movie has in its back pocket for the first thirty minutes. The graceful efficiency with which Siodmak introduces the characters, especially Bruce, is more than commendable, but once the exposition is out of the way, the film settles into a groove that goes on a bit too long with too little direction: "there's someone in this spooky old house who wants to screw around with the possible recipients of an inheritance" was old hat years before '46, but the film's first and much of its second acts cling tightly to that plot form like it needs to be teased out carefully and precisely, or else we'll all be hopelessly lost. It's only the characters, which largely means the actors, who keep it purring along for most of this stretch, and with the cast primarily inhabited by second-stringers, that means that it's a bit rocky here and there. King, in particular, is colorless and flat: as the film's only woman of any serious importance, there's far more weight and attention on her than her one-note declamatory performance style can justify. And Naish, he plays-a de Italian with da, how you say, issa great-a big cartoon. At least Alda is a beguiling leading man, smooth enough to see why so many people would fall for his tricks without stopping to notice how shoddy his patter is, and unctuous enough that we, in the audience, have to notice that, likable or not, he's certainly a bit of a shit.

But back to Lorre, who's only third-billed and maybe not even the third-biggest role until the climax, but damn, does he dominate the film. No matter how ominously luxurious and dead the gaping sets appear, and no matter how uncanny the accumulation of hints that there might be a hand afoot, The Beast with Five Fingers would be thin gruel as a horror film without the creepy little Austro-Hungarian there to add a sense of foreboding. Whatever his gifts, Lorre's voice and screen presence limited him considerably in the types of emotions he could stir: he could be a nervous force of rodent-like pathos, he could be an threatening bundle of sinister undertones or, frequently, both. He's much more the former than the latter in The Beast with Five Fingers, although director Robert Florey uses the actor with stiletto-like precision: there are just enough moments where we cut to a shot of Lorre with a sneaky dark look on his face, turned inward in a most inscrutable fashion, that we can't ever shake the feeling that something is wrong, whether with the character or with the movie as a whole. It's the energy that Lorre provides, in effect, that makes The Beast with Five Fingers a horror movie in the first place, at least until that hand finally shows its face.

Which comes late enough that it would be a dirty trick to talk about it very much, other than to point out that its superlative filmmaking, by 1946 standards or our own: there is a grand total of one shot where it feels like a special effect. And while it would be tempting to chalk that up to the acting in response to it, Florey gives that hand some close-ups, all the better to sell the illusion, tremendously well. The third-act freakout in which the hand does most of its work is peerless horror filmmaking, nasty, explicit, and convincing like nothing else in that generation.

I'd say that one wonders how they could have gotten away with it, except that part is obvious: with an unforgivable final two scenes that retrench to the usual "don't worry, nothing paranormal here" attitude of the more squeamish Hollywood tradition, old-dark-house movies in particular. First up comes a tedious exposition dump that's blunt and artless in exactly the way that the film's initial set-up is elusive and sophisticated and cunning, and it's very nearly the twin to the legendarily bad psychiatrist scene in the home stretch of Psycho. And what's really sad is that this is not, in fact, the worse of those two final scenes: the very last scene is outright comedy, with Naish's big honking stereotype looking directly in the camera and mugging about hey, whatta ya gonna do, these old-a spooky houses. It's so unbelievably wretched that you don't just want to dock points for it: you want to overlook how much of the prior to that is craftily plotted, smartly acted and tensely directed, and declare the whole thing to be a misfire.

I mean, let's not do that. The Beast with Five Fingers has much that is admirable: it may be more of a mystery than a real horror film, but it's a pretty good mystery, at that. If studio horror had to be put in cold storage for a few years, there could have been a much worse send-off than this: it's not perfect, but it's got enough atmosphere and well-drawn characters to fuel a good many of the tired low-budget genre flicks that popped up like weeds in the years following it.

Body Count: 3, but none of them are the ones who arguably deserve it the most.

At the moment, let's spend a moment with what amounts the the last big studio attempt at horror in the 1940s: the 1946 Warner Bros. production The Beast with Five Fingers, which premiered at the tale end of that year (on Christmas Day, in fact), and had most of its run in 1947. It's an awkward fit of company identity and historical importance: Warner's was never one of the biggest players in the genre, and much of the film, especially its infamously stupid, winking ending, feels like a conscious attempt to distance the movie from its own content. Which is, as you can maybe guess from the title, a disembodied hand that murders people.

Among its efforts to not be quite so much about a disembodied hand, The Best with Five Fingers spends the largest part of its running time as a murder mystery stealing from the "old dark house" motif. Around the beginning of the 20th Century, American expatriate Francis Ingram (Victor Francen) lives in a grand old mansion outside of a small town in Italy. He's attended by, he thinks, his best friends and most trusted confidants: lawyer Duprex (David Hoffman) is obviously just there for the slightly batty rich client; secretary Hilary Cummins (Peter Lorre), 20 years in Ingram's employ, is interested solely in the access his position affords him to Ingram's impressive library of astrological arcana, with which Hilary hopes to reconstruct the great lost studies of the pseudoscience; nurse Julie Holden (Andrea King), brought on some while back to care for Ingram after he suffered a stroke that paralysed his right side, has since moved from "kind medical professional" to "borderline prisoner under the obsessive control of a selfish tyrant". That leaves only our hero, Bruce Conrad (Robert Alda), and he's nothing but a con-man: a genial, charismatic con-man introduced in the film's opening scene by fleecing American tourists out of $50 for some worthless fake antiques, and then offering up just enough flim-flam to local cop Ovidio Castanio (J. Carrol Naish) so that the officer can feel like he hasn't totally abandoned his professional ethics. So it's hard to imagine that he sees Ingram as anything but a friendly mark.

Even with these enormous caveats, these are Ingram's friends and confidantes, and they are the people he asks to attest in writing to his evident sanity as he prepares to put up a new will. That, of course, means that he's about to do, which happens by accident, it seems, as he falls down a flight of stairs in his wheelchair. And this is the start of everyone's woes: for Ingram's only relatives are a pair of the worst kind of shitty, entitled Americans, father Raymond Arlington (Charles Dingle) and son Donald (John Alvin), and when they learn that Ingram's mysterious new will named Julie as the sole heir to his estate, they smell a rat immediately. But shenanigans of that sort are soon going to be a rather small priority to anybody but the grasping asshole Arlingtons: cued by a light in the masoleum where Ingram was interred, the rest of the cast finds that the corpse has been desecrated, its left hand removed. And right around the same time, the house is filled with the mournful tones of a Bach piece that Bruce re-set to be performed with one hand, as a great favor to the frustrated, crippled pianist. Different characters leap to conclusions at different times: Hilary, who was almost strangled to death by Ingram's incredibly powerful left hand shortly before his death, is the first to be sure that the dead man's missing body part is now haunting the house, and the first strangulation murder would seem to bear him out.

At no point was The Beast with Five Fingers going to be an all-time classic work of cinema, but given the tenuous state of horror in 1946, it acquits itself beautifully. Screenwriter Curt Siodmak, one of the key voices at Universal during its shift in the '40s to B-horror, thought that putting the weird-looking, weird-sounding Lorre in the role of Hilary broke the tension a bit too much, but frankly, Lorre is the best thing the movie has in its back pocket for the first thirty minutes. The graceful efficiency with which Siodmak introduces the characters, especially Bruce, is more than commendable, but once the exposition is out of the way, the film settles into a groove that goes on a bit too long with too little direction: "there's someone in this spooky old house who wants to screw around with the possible recipients of an inheritance" was old hat years before '46, but the film's first and much of its second acts cling tightly to that plot form like it needs to be teased out carefully and precisely, or else we'll all be hopelessly lost. It's only the characters, which largely means the actors, who keep it purring along for most of this stretch, and with the cast primarily inhabited by second-stringers, that means that it's a bit rocky here and there. King, in particular, is colorless and flat: as the film's only woman of any serious importance, there's far more weight and attention on her than her one-note declamatory performance style can justify. And Naish, he plays-a de Italian with da, how you say, issa great-a big cartoon. At least Alda is a beguiling leading man, smooth enough to see why so many people would fall for his tricks without stopping to notice how shoddy his patter is, and unctuous enough that we, in the audience, have to notice that, likable or not, he's certainly a bit of a shit.

But back to Lorre, who's only third-billed and maybe not even the third-biggest role until the climax, but damn, does he dominate the film. No matter how ominously luxurious and dead the gaping sets appear, and no matter how uncanny the accumulation of hints that there might be a hand afoot, The Beast with Five Fingers would be thin gruel as a horror film without the creepy little Austro-Hungarian there to add a sense of foreboding. Whatever his gifts, Lorre's voice and screen presence limited him considerably in the types of emotions he could stir: he could be a nervous force of rodent-like pathos, he could be an threatening bundle of sinister undertones or, frequently, both. He's much more the former than the latter in The Beast with Five Fingers, although director Robert Florey uses the actor with stiletto-like precision: there are just enough moments where we cut to a shot of Lorre with a sneaky dark look on his face, turned inward in a most inscrutable fashion, that we can't ever shake the feeling that something is wrong, whether with the character or with the movie as a whole. It's the energy that Lorre provides, in effect, that makes The Beast with Five Fingers a horror movie in the first place, at least until that hand finally shows its face.

Which comes late enough that it would be a dirty trick to talk about it very much, other than to point out that its superlative filmmaking, by 1946 standards or our own: there is a grand total of one shot where it feels like a special effect. And while it would be tempting to chalk that up to the acting in response to it, Florey gives that hand some close-ups, all the better to sell the illusion, tremendously well. The third-act freakout in which the hand does most of its work is peerless horror filmmaking, nasty, explicit, and convincing like nothing else in that generation.

I'd say that one wonders how they could have gotten away with it, except that part is obvious: with an unforgivable final two scenes that retrench to the usual "don't worry, nothing paranormal here" attitude of the more squeamish Hollywood tradition, old-dark-house movies in particular. First up comes a tedious exposition dump that's blunt and artless in exactly the way that the film's initial set-up is elusive and sophisticated and cunning, and it's very nearly the twin to the legendarily bad psychiatrist scene in the home stretch of Psycho. And what's really sad is that this is not, in fact, the worse of those two final scenes: the very last scene is outright comedy, with Naish's big honking stereotype looking directly in the camera and mugging about hey, whatta ya gonna do, these old-a spooky houses. It's so unbelievably wretched that you don't just want to dock points for it: you want to overlook how much of the prior to that is craftily plotted, smartly acted and tensely directed, and declare the whole thing to be a misfire.

I mean, let's not do that. The Beast with Five Fingers has much that is admirable: it may be more of a mystery than a real horror film, but it's a pretty good mystery, at that. If studio horror had to be put in cold storage for a few years, there could have been a much worse send-off than this: it's not perfect, but it's got enough atmosphere and well-drawn characters to fuel a good many of the tired low-budget genre flicks that popped up like weeds in the years following it.

Body Count: 3, but none of them are the ones who arguably deserve it the most.