Blockbuster History: The kiler theme parks of Michael Crichton

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: the failed theme park of Michael Crichton's 1990 novel Jurassic Park finally opens for business in Jurassic World, with the expected results. Let us now admire the career-long fixation the author apparently had with murderous versions of Disneyland.

It is not possible, and has not been since 1993, to bring up Westworld without immediately thinking about it in terms of Jurassic Park, either the book or the movie. But let us try to avoid that temptation as much as possible, in all fairness to the 1973 movie that was author Michael Crichton's first foray into directing (and one of his small number of screenplays that weren't based on a book). Let us also note that the 20 years between Westworld and Jurassic Park is a smaller gap than the 22 years separating Jurassic Park from 2015, when I write these words, and let us as a result feel extraordinarily old.

The film takes place right smack in Crichton's thematic wheelhouse: it's about people trying to create a contained system to cheat nature (human or otherwise), and having that system blow up in their face. Sometime in the near future that looks and acts exactly like 1973, there exists a theme park complex named Delos (which just screams "I'm a mythological reference!", and it's the name of a Greek island of considerably religious significance, though what possible thematic point Crichton is trying to score here, I can't begin to imagine). Here, in the middle of a desert, are three individual resorts, Westworld, Romanworld, and Medievalworld, and they are populated by extraordinary, life-like robots inhabiting replicas of the American frontier, Imperial Rome, and a medieval English castle. Here, those guests willing to pay out the $1000/day price tag can enact any fantasy they want in one of the three environments, at absolutely no physical risk to themselves.

Among the tourists we meet upon our arrival at the complex are John Blane (James Brolin) and Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin) of Chicago. John has been to Westworld before, and he thinks that the no-stakes shooting and whoring opportunities provided by the park will re-inject some old-fashioned masculinity into his newly-divorced and thoroughly depressed buddy. Unfortunately, they arrived just as the Delos robots were starting to suffer from a kind of malfunction that passes through them like an infectious disease - at this point, computer viruses were a theoretical possibility, but they wouldn't appear in reality for almost another decade, and the disease terminology wouldn't be coined until 1984 - and while the park's chief supervisor (Alan Oppenheimer) has his whole team working to figure out what's going on while it's still tiny annoyances rather than any kind of programming flaw that could actually interfere with the guests, there'd be be no movie at all if he succeeded, now would there?

There are many lovely things about Westworld, and many things that are just kind of there, but it's best to start with the elephant in the room: Delos makes no goddamn sense. It's easy to buy the idea of a playground where adults can pretend to be knights, cowboys, and... whatever is meant to happen in Romanworld; the implication is that it's the "constant orgies, presumably with robots that look like 12-year-olds" park, but it's very clearly the odd man out, and the film spends almost no time in it until the inevitable robot uprising. Anyway, the appeal of Delos in the abstract makes sense (though spending days on end in a simulated Wild West and only getting involved in a shootout once or twice per day sounds stultifying). But the way Westworld fleshes out that concept is so absurdly self-defeating that I'm surprised most of the details made it to a second draft - I could spend the rest of this review nitpicking the script and concept, but that would be tedious, so let's stick with just one of my biggest gripes. It's great that the guns don't work because they detect human body heat; what about the swords? Why give the robots live ammunition in the first place? That was two, sorry.

Even the way it's staged rings false: the streets of Westworld don't look like a town packed with tourists, or even lightly populated with the very rich, they look like three real humans are poking around a world full of robots. It's all immensely unpersuasive, in the broad strokes and the specific details, and the whole structure of the film feels like you could knock it all down with a mean look.

The central conceit of Westworld is so flimsy that it's only possible to take it seriously at all by treating it as a metaphor. Which, fortunately, can be done pretty easily. And that metaphor is all about the crisis of American malehood in the immediate post-feminist era. That sounds like exactly the last topic in all the world that a sane person would want Michael Crichton to address, but actually, Westworld is rather smart in its diagnosis about the inherent immaturity and foolishness of trying to regress to a state of mythic, purified masculinity. The basic self-righteous smugness shown by John Blane - the rhyme with "John Wayne" could hardly be coincidental - as he pushes his nervous buddy into living out a sanitised fantasy about the most virile place and time in the history of North America is a perfect depiction of a personality building walls to protect itself, and Brolin is just about the perfect person to embody all of those traits. He is an egotist who doesn't realise that he has nothing to be egotistical about, and it's what costs him as the film progresses.

At the same time, the film doesn't try to undersell the appeal of the place it creates - Benjamin gets a fantastic line delivery when, at the end of his first day in the (still functional) Westworld, he laughs "John? This place is really fun!", and in so doing succeeds at convincing us that Delos is an actual vacation spot more effectively than anything in the movie outside of its opening commercial (written by an actual ad executive, giving it the perfect stilted come-on feeling). So this is not a philosophical harangue - it's critical of the blinkered state of mainstream masculinity from a place that understands and sympathises with the urges of that masculinity.

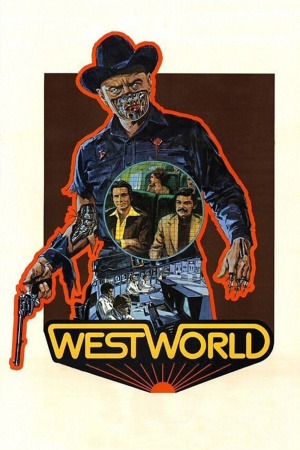

Ultimately, though, the film does want to be a techno-thriller, and purely at the level of genre mechanics, it succeeds. Crichton's directing is anonymous at best, but that's partially a result of his self-conscious desire to copy the trappings of a generic Western, since Westworld is meant to be the ultimate expression of of a generic Western (or not-so-generic: there's a slow-motion shootout that could only be regarded as a deliberate parody of the then-recent The Wild Bunch). And for the villain of the piece, Westworld nabbed one of the all-time great killer robots: Yul Brynner as a gunslinger 'bot plainly modeled on the actor's role in The Magnificent Seven. Despite Brynner's top billing and prominence in the film's ad campaign, his gunslinger only appears intermittently in the film's first hour, turning into a an active threat only near the end, when Delos is all gone to hell. But the film makes all of his limited screen time count for a lot: his lean build and tense poses, and his unchanging expression of barely-contained rage are tremendously threatening and effortlessly iconic, and it's no wonder that the popular understanding of the movie elevates him above all the rest, even though he's largely defined by his absence.

Brynner and the character are so good that they almost make it possible to ignore that the film hasn't earned them. For if we're to allow that the sci-fi elements of Westworld are a metaphor when the subject at hand is the arrogance of the individual male, we can't really play the same trick when the sci-fi elements are a literal expression of scientific hubris and the collapse of a system. For the gunslinger to be a great villain, stalking the characters through the desert and into the guts of Delos, we have to believe in its reality, and Westworld does such a piss-poor job of presenting this colony of malfunctioning robots as something that could possibly exist the way the film wants it to, there's no real way to take the plot seriously enough that when the programming finally snaps and the robots run amok, we can feel the tension shift. Brynner has amazing screen presence and Crichton and director of photography Gene Polito do an amazing job framing the gunslinger to make it absolutely terrifying. But it is terrifying in a vacuum; it's hard to accept it as the embodiment of a system breaking down and killing its creators, because it's virtually impossible to believe that system ever functioned in the first place.

It is not possible, and has not been since 1993, to bring up Westworld without immediately thinking about it in terms of Jurassic Park, either the book or the movie. But let us try to avoid that temptation as much as possible, in all fairness to the 1973 movie that was author Michael Crichton's first foray into directing (and one of his small number of screenplays that weren't based on a book). Let us also note that the 20 years between Westworld and Jurassic Park is a smaller gap than the 22 years separating Jurassic Park from 2015, when I write these words, and let us as a result feel extraordinarily old.

The film takes place right smack in Crichton's thematic wheelhouse: it's about people trying to create a contained system to cheat nature (human or otherwise), and having that system blow up in their face. Sometime in the near future that looks and acts exactly like 1973, there exists a theme park complex named Delos (which just screams "I'm a mythological reference!", and it's the name of a Greek island of considerably religious significance, though what possible thematic point Crichton is trying to score here, I can't begin to imagine). Here, in the middle of a desert, are three individual resorts, Westworld, Romanworld, and Medievalworld, and they are populated by extraordinary, life-like robots inhabiting replicas of the American frontier, Imperial Rome, and a medieval English castle. Here, those guests willing to pay out the $1000/day price tag can enact any fantasy they want in one of the three environments, at absolutely no physical risk to themselves.

Among the tourists we meet upon our arrival at the complex are John Blane (James Brolin) and Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin) of Chicago. John has been to Westworld before, and he thinks that the no-stakes shooting and whoring opportunities provided by the park will re-inject some old-fashioned masculinity into his newly-divorced and thoroughly depressed buddy. Unfortunately, they arrived just as the Delos robots were starting to suffer from a kind of malfunction that passes through them like an infectious disease - at this point, computer viruses were a theoretical possibility, but they wouldn't appear in reality for almost another decade, and the disease terminology wouldn't be coined until 1984 - and while the park's chief supervisor (Alan Oppenheimer) has his whole team working to figure out what's going on while it's still tiny annoyances rather than any kind of programming flaw that could actually interfere with the guests, there'd be be no movie at all if he succeeded, now would there?

There are many lovely things about Westworld, and many things that are just kind of there, but it's best to start with the elephant in the room: Delos makes no goddamn sense. It's easy to buy the idea of a playground where adults can pretend to be knights, cowboys, and... whatever is meant to happen in Romanworld; the implication is that it's the "constant orgies, presumably with robots that look like 12-year-olds" park, but it's very clearly the odd man out, and the film spends almost no time in it until the inevitable robot uprising. Anyway, the appeal of Delos in the abstract makes sense (though spending days on end in a simulated Wild West and only getting involved in a shootout once or twice per day sounds stultifying). But the way Westworld fleshes out that concept is so absurdly self-defeating that I'm surprised most of the details made it to a second draft - I could spend the rest of this review nitpicking the script and concept, but that would be tedious, so let's stick with just one of my biggest gripes. It's great that the guns don't work because they detect human body heat; what about the swords? Why give the robots live ammunition in the first place? That was two, sorry.

Even the way it's staged rings false: the streets of Westworld don't look like a town packed with tourists, or even lightly populated with the very rich, they look like three real humans are poking around a world full of robots. It's all immensely unpersuasive, in the broad strokes and the specific details, and the whole structure of the film feels like you could knock it all down with a mean look.

The central conceit of Westworld is so flimsy that it's only possible to take it seriously at all by treating it as a metaphor. Which, fortunately, can be done pretty easily. And that metaphor is all about the crisis of American malehood in the immediate post-feminist era. That sounds like exactly the last topic in all the world that a sane person would want Michael Crichton to address, but actually, Westworld is rather smart in its diagnosis about the inherent immaturity and foolishness of trying to regress to a state of mythic, purified masculinity. The basic self-righteous smugness shown by John Blane - the rhyme with "John Wayne" could hardly be coincidental - as he pushes his nervous buddy into living out a sanitised fantasy about the most virile place and time in the history of North America is a perfect depiction of a personality building walls to protect itself, and Brolin is just about the perfect person to embody all of those traits. He is an egotist who doesn't realise that he has nothing to be egotistical about, and it's what costs him as the film progresses.

At the same time, the film doesn't try to undersell the appeal of the place it creates - Benjamin gets a fantastic line delivery when, at the end of his first day in the (still functional) Westworld, he laughs "John? This place is really fun!", and in so doing succeeds at convincing us that Delos is an actual vacation spot more effectively than anything in the movie outside of its opening commercial (written by an actual ad executive, giving it the perfect stilted come-on feeling). So this is not a philosophical harangue - it's critical of the blinkered state of mainstream masculinity from a place that understands and sympathises with the urges of that masculinity.

Ultimately, though, the film does want to be a techno-thriller, and purely at the level of genre mechanics, it succeeds. Crichton's directing is anonymous at best, but that's partially a result of his self-conscious desire to copy the trappings of a generic Western, since Westworld is meant to be the ultimate expression of of a generic Western (or not-so-generic: there's a slow-motion shootout that could only be regarded as a deliberate parody of the then-recent The Wild Bunch). And for the villain of the piece, Westworld nabbed one of the all-time great killer robots: Yul Brynner as a gunslinger 'bot plainly modeled on the actor's role in The Magnificent Seven. Despite Brynner's top billing and prominence in the film's ad campaign, his gunslinger only appears intermittently in the film's first hour, turning into a an active threat only near the end, when Delos is all gone to hell. But the film makes all of his limited screen time count for a lot: his lean build and tense poses, and his unchanging expression of barely-contained rage are tremendously threatening and effortlessly iconic, and it's no wonder that the popular understanding of the movie elevates him above all the rest, even though he's largely defined by his absence.

Brynner and the character are so good that they almost make it possible to ignore that the film hasn't earned them. For if we're to allow that the sci-fi elements of Westworld are a metaphor when the subject at hand is the arrogance of the individual male, we can't really play the same trick when the sci-fi elements are a literal expression of scientific hubris and the collapse of a system. For the gunslinger to be a great villain, stalking the characters through the desert and into the guts of Delos, we have to believe in its reality, and Westworld does such a piss-poor job of presenting this colony of malfunctioning robots as something that could possibly exist the way the film wants it to, there's no real way to take the plot seriously enough that when the programming finally snaps and the robots run amok, we can feel the tension shift. Brynner has amazing screen presence and Crichton and director of photography Gene Polito do an amazing job framing the gunslinger to make it absolutely terrifying. But it is terrifying in a vacuum; it's hard to accept it as the embodiment of a system breaking down and killing its creators, because it's virtually impossible to believe that system ever functioned in the first place.

Categories: action, blockbuster history, science fiction, thrillers, westerns